The one thing you will not find in school-or even on Architecture Registration Exams-is a course on how to get work, yet it is one of the most basic needs of any design practice. In fact, if you don't have an equal ability to experiment in getting work as you do in doing work you would be fortunate to make it past the first five years.

UpStarts is a series of features on the foundations of contemporary practice. It will have a global reach in which practices from Europe, North America, Asia, and beyond will be asked to address the work behind getting the work, and the effect of cultural contexts. The focus will be on how a practice is initiated and maintained. In many ways, the critical years of a fledgling design partnership is within the initial five years, after the haze and daze of getting it off the ground. UpStarts will survey the first years of practice as a tool for tracking the tactics of the rapidly evolving methods for sustaining a practice.

The first series is a dialogue with Studio Sputnik in Rotterdam, 51n4e in Brussels, and Andrew Maynard in Melbourne. Mason White's dialogue took place with Jaakko van't Spijker of Studio Sputnik by email in late July 2005. Studio Sputnik officially started up their practice in 2001.

1. My first question is pretty simple. I am wondering how you initiated Studio Sputnik? How did you know it was the right time in your career to start a private practice?

Studio Sputnik started off when we squatted in an old attic of a building while we were still students. With a group of about eight friends, we wanted to be able to work intensely on our diploma projects in our own space-at Technische Universiteit Delft they did not provide inspiring studio facilities. After having graduated at the end of 1996, we all went to work in various ambitious offices in Rotterdam and Amsterdam, but a core group kept coming back together to work on competitions at night and on weekends. Gradually, more serious projects came up and the three of us decided to form a partnership. We initially combined our own work with freelance activities-you could say we kind of were our own temp agency. Since 2003 we have been able to generate our own income.

Due to our slow conception we never had to decide when the time was right. We were just around, ready to grab chances that came by, but not under a now-or-never pressure, as we were doing interesting work and getting valuable experience in what we did outside Studio Sputnik.

The decisive moment was the Snooze book. In 2002, we had been doing stuff on and off for about five years, but we felt we were still unable to articulate what our office was about exactly. What marked its difference with all the other young and emerging offices, of which there were and always are a lot in Holland? After many thoughts and discussions we were able to articulate the undercurrent embedded within-often subconscious, and not at all explicit-most of our work: a special interest in the mass-culture side of society. We wrote a research proposal for a study of this and it was granted by the Dutch subsidy machinery. This meant that: (1) We could develop ourselves by devoting time to digging into our fascinations and obsessions; and (2) We received exposure by publishing our research. After the book came out in the second half of 2003, things suddenly became easier than they were before. We were immediately able to apply our new insights in a competition in Taiwan, where we received 2nd prize. We were granted the Charlotte Kohler Award 2004 for emerging practice, and we won an invited competition in Rotterdam.

So the story of the right time in our careers to get ourselves started bites its own tail. In hindsight, we wrote the book at the right moment, though it was that very book that created the moment.

![]()

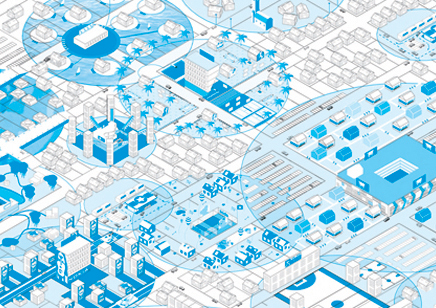

Left: SnoozeCity from Snooze (2003).

Right: The idea of Snooze where meaning is based not on image but on total experience.

Click images to enlarge

2. After Snooze, how were you able to make the transition from an experimental research-based practice to convincing possible clients to hire you for realizing work that addresses mass culture? Did the book not pigeonhole you as a practice less interested in materializing work?

It is hard to identify the different transitional moments in the development of our office. Our profession is very much based on individual assignments that arise from what appears to be luck. It is not as if we sat down and thought, "Now we have to make the transition from a theoretical to a practical practice." In retrospect, it seems to us as if the publication pushed more lucky moments our way. To start with, it enabled us to express what distinguishes us. This was an important moment in Holland-and particularly in Rotterdam-when many, many more young practices were-and still are-starting up. Luck turned in our favor in several ways. First, the Snooze book made us interesting in the Dutch architectural scene, even though we had not yet built anything. We were invited to present the book in a debate evening at the Netherlands Architecture Institute , moderated by Aaron Betsky . Betsky read the book, liked it a lot and told others. The Charlotte Kohler Award jury noticed the book, visited us and gave us the award. Second, having expressed for ourselves what we try to do in our office, Snooze made us look out for opportunities with a clearer focus than we had done before.

The Taiwan competition was about attracting more tourism to several of Taiwan's beautiful nature reserves. Tourism infrastructure being exactly the area where architecture and mass culture meet made this competition very interesting for us. We entered and ended up winning second prize.

We decided to enter the mass-housing market by advertising our office in a catalogue buildings magazine. Several reactions followed and just a few weeks ago construction has finished on the first building commission resulting from the advertisement. We are now seriously trying to wedge a foot into the huge market of private housing, a market that is largely defined by tasteless neoclassical prefabs.

The book did not so much pigeonhole us as theorists but made us strange outsiders for some large clients who had never heard of us before. For instance, we were invited to enter a housing competition held by a large housing corporation in Rotterdam. Next to established offices like MVRDV and Soeters Van Eldonk , I suppose we were given a wild card to see what we would come up with. We ended up winning. That is how the Delfshaven housing commission occurred-indirectly from having published Snooze , but directly from the concept we came up with in competition with other offices.

Left: Sun Moon Stars, Taiwan (2003), invited competition, 2nd prize.

Right: Delfshaven Housing, Delfshaven, Holland (2004), invited competition, 1st prize.

Click images to enlarge

I think, for us, it is not important to have made a transition from theoretical to practical office. We actually avoid having to choose, as building becomes too practical and banal without having theoretical reflection to do, and theory/teaching becomes too divorced from real life without actual building.

3. It's funny that you talk about trying to tap into the private housing market there. In the US, it is the public housing market that seems more difficult for architects to tap into. Has the cultural support for architects - so notorious in Holland - been instrumental in breeding young architectural practices with public commissions, or is there other politicking behind the scenes that figure in? Do tell.

Also, you mentioned advertising the office in a magazine. Is that common for young practices in Holland?

At the moment, the difference between public and private is very blurry in Holland. It is clear that when someone obtains a piece of ground and wishes to build a house there it is private. That is what I meant by the market we want to tap into.

But there is a lot more going on: Most housing co-operations that were traditionally responsible for public housing have recently been privatized and are now operating comparable to private developers. At the same time, commercial developers are often being forced to construct a certain percentage of public housing in their developments. Both corperations and developers in Holland have been open for employing (alone or in co-operation with Dutch subsidy funds, local governments or the European Competition policy) for experimental young offices in the last ten to fifteen years. But those days seem to have come to an end in a time of recession and decreasing demand. The market is currently very tough for beginners; the SuperDutch days are no more. Simultaneous to this, in the last five years or so, the Dutch architectural profession has started to discover the individual housing market. Carel Weeber, enfant terrible of the Dutch architecture scene for as long as anyone can remember, dubbed it "wild living " and so it got hot. However, despite a lot of cool-sounding polemics concerning the subject, as far as we are concerned architects don't seem to have done anything about their attitude or approach when it comes to this market. This means they remain too expensive and elitist for the average daredevil that goes for a dream house. Which in turn means that readymades out of the catalogue are generally the only option for a site owner. One of our ambitions is to see if we can slip into the empty space that exists between "proper" architecture on the one hand and "bad taste" catalogue housing on the other.

The Dasrath house is our first probe and it looks promising. We got that commission by advertising in a "bad taste," very low threshold, vernacular magazine full of articles about and adverts for neotraditional farmhouses and neoclassical mansions. It was in part a statement, almost a kind of art project, to see our advert in that magazine. In part it was also a provocation because the Dutch Institute for Architects (BNA) forbids such actions with the reason that law firms, doctors and architects should not compete in the open and behave as gentlemen and -women in the face of the public. So in answer to your question, it is absolutely not done to advertise as an architect in Holland. In the last but not least part, we were seriously looking for work, and luckily we ended up with one built and one currently in design.

4. Besides renegade advertising spots in magazines, what other techniques have you used to try to get work? Or has the old standby of competitions and requests for qualifications (RFQ) been enough to keep Sputnik going in the early years?

This one is, of course, hard to answer. If there is no secret through which we acquire our work, we are completely uninteresting. However if we do have a secret, we will not reveal it.

Suffice it to say that the Snooze book has done a lot for us and the power of networks cannot be overstated. Somehow the intangible world of theory and the daily reality of commissions are linked. The nice thing about taking the risk of going public with thoughts and ideas is that you loose control over them. The book is for sale in many stores in the real world as well as on the Internet and has been bought by libraries. This means that we have lost track of who knows about us.

The way we were invited to the Delfshaven competition remains a mystery to us. We have tried to trace back where the crucial link was made. It appears that a recently appointed property manager studied in Delft at the time we were teaching there and had somehow heard about us being interesting teachers doing cool research in our own studio. How can you develop a marketing strategy that increases commissions that come about like that?

Our other big commission is an industrial complex in Nigeria. This one simply came to us through the grapevine. Someone who was involved with the project knew someone who knew we were architects and just phoned up to see if we were interested in introducing ourselves. Again, could we have marketed ourselves into that position?

Left: Stadstuinen (City-Gardens), Hoogvliet, Holland (2005), commission for WiMBY, ds+V.

Right: Dasrath House, Hendrik-Ido-Ambacht, Holland (in progress), private commission.

Click images to enlarge

We just finished a competition entry for the WiMBY! Hoogvliet project by Crimson . They definitely knew about the book, knew about us, and knew they wanted non-standard stuff. Here maybe marketing is about wedging your foot into something called the Dutch young architects scene.

All in all, I believe our marketing, if it can be called that, has been about two things. One, pushing our luck by way of perseverance and time after time making ever more attempts in vain to get to be known with clients and to obtain jobs. And two, having a story, or being able to express what our office and way of working is about. In the last few years, what we are about has been condensed into a two-word mantra-Radical Everyday , meaning we try and take the ordinary to the edge. This is a very pragmatic attitude that makes sense and is interesting to diverse people, including pragmatic clients and intellectual critics.

5. In a post-SuperDutch Holland, with its increasing privatization, it would seem that today's young practices require greater resilience in their early years. What kind of work would you like to break into in the next five years, and how do you plan to get there?

A post-SuperDutch Holland ... I like the sound of that as being our current context! I would like to start answering your question by giving you a quote from an article that was written last year by Wouter Vanstiphout , the vanguard Rotterdam historian and critic. It reflects the mood here and it reflects pretty accurately how we in Sputnik operate.

"Liberated from the paranoid hierarchies of SuperDutch ...[architects] will be able to become fighters, entrepreneurs, activists, and opportunistically add their signatures to the bizarre bazar that this country is becoming. ... They will design spaces that are heaven on earth for their users, but that fill passers-by with disgust. Their contributions will be minimal in comparison to the size of the city, but will be sparklingly present in comparison to their surroundings. [These architects] will be called Dirty Minimalists. They will change your world."

-from Wouter Vanstiphout , Dirty Minimalism, Archis #5, 2004.

I suppose we are being resilient, but that doesn't feel like a bad thing. Actually, there are a lot of opportunities for grabs, but it seems to require an attitude that some warn us against. We are trying to do everything we like! When asked whether we are going to be theorists or builders, or whether we want to be commercial or cutting edge designers, we always avoid having to choose. Especially earlier generations seem to frown upon such an attitude. We like to look at the phenomenon of the prize fighter airlines that have come to stay in the airline business over the last ten years or so.

In Europe all the big, elitist, comfortably established airlines (KLM, British Airways, etc.) simply denied the budget carriers' existence for the first five years, as if they were some kind of annoying but harmless bug. They then tried to crush them under their heels to discover they were un-crushable. The budget liners have changed the whole concept of air travel from an elite thing for the happy few to a mass opportunity with an ever lower threshold. The more inventive ones like easyJet expanded beyond flying into a group of related companies like easyCar , easyCruise , easyMoney , etc. Imagine KLM starting a music label or mortgage company! Attaining and keeping up a refreshing, provocative, engaged, cheeky and non-pigeonholeable attitude is our first ambition for the coming five years. In terms of building, we are working on starting up a new firm that will deal with private houses (to be called Gazebo Systems ) and, of course, we also harbor that typical architectural megalomaniac streak, which we would love to apply to a major public building. We are definitely going to continue combining doing (designing and building) and thinking (writing and teaching), as we hate the idea of ever having to choose between those.

Creative Commons License

UpStarts is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.5 License .

/Creative Commons License

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.