How can a park be designed to serve as infrastructure(s)? Thinking not in terms of metaphor alone. But rather a park as the architecture for numerous designed outcomes. Park as infrastructure, means park as platform not only designed object/scape. From a singular tool to multivalent toolkit. It is important in such discussion to think of the less immediate impact. Of social design, the design of relationships. Such a platform-as toolkit-may result from more efficient, and stack(ed) programming. Thus maximizing urban spaces, suburban spaces, available spaces, that are under-performing. In essence, we should think about the best ways to maximize our various infrastructural corridors: utility, transportation, waterways et al.

Another approach involves returning to and reusing brown-fields and other post-industrial sites. In recent years, especially on reclaimed land, one has witnessed the return of the urban park. Examples include New York's High Line, Seattle's Olympic Park, Chicago's Millennium Park or the London 2012 Olympic Park. Generally these parks are part of a larger urban regeneration strategy. Which relies on large amounts of capital coming from public and/or private investment.

Companies making that scale of investment expect a benefit; either to their brand-image or through sales, and the city receives improvements – and parks – in exchange. Yet, there is a danger here. In terms of the question of value. What is the value of a park? Is it just a question of real estate value, or green leisure space?

Is a green, sustainable city, literally a green city, full of parks? Should a park be more than a park? SWA landscape architects and urban designers have been at the forefront amongst firms working on this recent wave of such urban park-lands. With projects that are centered right at the intersection between urbanism, parks and infrastructure. For instance, in Houston, their work with the Buffalo Bayou Partnership BBP, resulted in the Buffalo Bayou Promenade.

That project dealt with the realities of contemporary Houston while launching larger efforts to restore the urban watershed and provide 23 acres of new and improved public recreation space. They have also provided landscape architectural services for Renzo Piano's California Academy of Sciences and are implementing their master plan for a rail-to-trails conversion for The Friends of the Katy Trail in Dallas.

Gerdo Aquino is president and principal of SWA Los Angeles studio. He also teaches graduate design studios at USC which focus on landscape infrastructure and its application to urban areas. Areas challenged by issues related to density, environmental degradation, health and accessibility. In the recently released book Landscape Infrastructure: Case Studies by SWA, Gerdo, along with fellow Los Angeles studio managing principal Ying-Yu Hung, explores issues of urban, infrastructural, landscapes. The publication also features essays by Charles Waldheim, Julia Czerniak and Adriaan Geuze.

I spoke with Mr. Aquino recently. Prior to calling, I wrote down a few thoughts. I wondered what the difference between landscape-urbanism and landscape-infrastructure was? Is it useful to make such a distinction, or is it more about framing an analysis of scaled systems? Performative (contemporary landscape infrastructure/urbanism) vs. pastoral (ecological restoration vs. reclamation)? What is the appropriate role for the park, to play within an urban context?

Should interdisciplinarity be the default response to contemporary problems of scale, eco-logics and urbanization? Are solutions like the AECOM/EDAW merger, inevitable? A simple calculation of market share, leading to Total Service Delivery?

What struck me most from my conversation with him was the level of concern for process. Surprisingly though this wasn't just used with regards to design processes (iterative, parametric et al). Rather it was the emphasis Gerdo placed on design as evolving out of a community conversation. Wherein discussion creates the right solution. Given the surge of interest in design as social activism or tool for community development, this view of the community process is a real statement about the possibilities for landscape infrastructure. Especially, in this country.

I began our interview by asking Gerdo to respond to the idea of not architecture but architectures. As in landscape as platform and maybe more specifically infrastructure. Particularly, with regards to operating at the growing intersection between landscape, urbanism and ecology.

Transcript...

Nam- I am interested personally, not so much in architecture in terms of singular buildings but more architectures plural. As in platforms, within the context of urbanism and development.

Gerdo- I like to think in terms of trying to understand a building's place within a landscape. So in that sense, I look at architecture as being part of a system and what are the systems. That are visible or invisible, systems that might tie architecture together? A lot of work at SWA and USC is about trying to find what is the dominant system in any landscape (rural, urban or suburban) that can act as an efficient network for making things better. More performative, programmed or ecological. It looks at the contiguous corridors that have changed uses over time and have adapted to a kind of contemporary society that is looking for ways to do other things. When I think of landscape infrastructure, I think of ways in which utility corridors could be maximized. Historically they have been these single use corridors, but now that infrastructure is kind of crumbling and many agencies, both locally and federally, are looking to reinvest, but also let it do more than what it has done in the past. For instance, really leveraging, under-utilized right of way(s).

Nam- In terms of maximizing these sorts of multi-use, multi-programmed, multi-functionality, infrastructures, I was talking with a friend the other day, and he was saying, "Why does it have to always be a park?". I responded to my friend that given the generally low per-capita ratio in many urban areas, off access to green, open space, "why not a park?". What would you have said to my friend?

Gerdo- I would have probably posed another question to him back, "what is a park?", and when asked this question, many people don't have a quick response. They think it is a) a trick question or b) that I am crazy. At USC, the landscape architecture and architecture students are all asking ourselves that question. What is a park? Does a park have to be green? Is a park, Central Park in NYC? You can look at Olympic Sculpture Park in Seattle, and it's basically a ramp. Parks have started to become this ambiguous thing, a cure-all for what ails the city. I think it is a bit more than that. I think architects, landscape architects and planners are going to have to figure out what are the issues. And you brought up the per-capita issue of access to open space. Here in Los Angles, there is such a place. I think it has the lowest per-capita ratio in all of California. Just East of Hollywood.

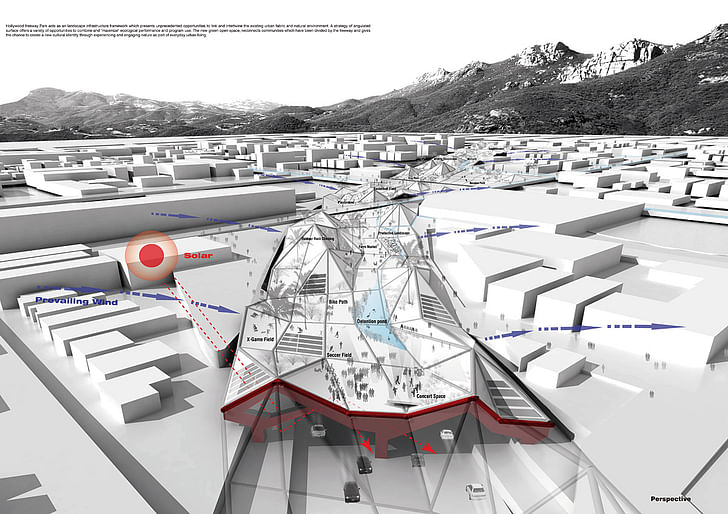

And in that area, there is a depressed section of the 101 freeway, cut like a valley. The state was going to spend half a billion dollars on about a one-mile section. To upgrade it. The community got together in and said if you're going to spend half a billion dollars for cars, why not spend another half billion and put a park over it. It is called the Hollywood Freeway Cap park. That was one of my studios for last year. We worked with the Hollywood Freeway Park Executive committee which is aligned with Friends of the High Line. The project would result in 40+ acres of green space.

The biggest issues are 1) you're capping over a freeway so how do you address carbon monoxide 2) you are creating a tunnel, and Californians are used to being in tunnels 3) all of which lead then to the third. Which is what is a park? Is a park green? Is it lawn, or maybe some sort of high performance medium that absorbs stormwater and creates clean water and maybe clean air. A breathing apparatus. So we are putting together a book for the Hollywood Freeway Park Executive committee of these proposals. That they can use as a marketing tool. To gather funding. Maybe from Obama's infrastructure monies.

Nam- You mentioned you had explored the High Line example, or in Dallas, where they are capping the freeway and expanding the whole Arts District. You used the word marketing. With these type of urban development projects, it seems one has to be concerned about the tension between public and private, funding, branding, rights-usage. Who is ultimately benefiting...

Gerdo- Sure some of those same concerns came up in a panel recently about landscape infrastructure in LA. We invited different folks. A developer, a lawyer, a landscape architect/planner and a city councilman. The issue came up, this is great, we understand what a cap park is, and it will provide certainly amenities or benefits in terms of public health or environment. What happens to all the land around it? A recent SCAG (Southern California Association of Governments) report on the park which focused on increased land values, F.A.R., towers around the park. A lot of the folks on the panel said that this is "what SCAG does". Ultimately, it will come down to the community. Really listening to what the community wants.

It was clear from the panel and the Q+A that nobody wants big towers. It has to be driven by a process that determines what is existing today. We don't want to drive out the people who deserve this open space and replace them with properties that are ten times more expensive.

Nam- You look at situations in Medellin or other South American countries that people are pointing to. Where they are trying to learn some of these lessons, of community involvement, social design, or something. How can we perhaps replicate and investigate some of those successes?

Gerdo- It seems like the mechanisms by which these caps parks or High Line type projects get funding is really creative. Whether private-public, corporate, or infrastructure funding, special bond measures. It seems like that money is somehow able to find itself into the construction of these projects.

The bigger challenge is long term maintenance. In the case of the Hollywood Freeway Cap Park, the Army Corps of Engineer said it is inside our right of way so we will maintain it. And that is a scary thought. Them maintaining or managing a park. It is just going to be blow and go, right? So everyone is freaked out. Trying to find some other precedents. The High Line for example, they estimated a $2.3 million a year maintenance budget. So when people think, wow it costs money to maintain. For the Hollywood Freeway Cap Park, no one seems to have solved their problem. Bryant Square is a good example of how a park maintenance and operations budget can be conceived, managed and implemented . They have an association of residents, business owners and maintain the park. And they have one of the most highly programmed parks. In terms of activities.

The one thing I want to say about parks, open space, etc, is that it is all really about looking at what has been done so we can figure out where we can go with parks. Creating new parks, new designs, new technology. We have to be able to justify. With metrics, what are the costs, and what are the successes and failures of recent projects.

Nam- The issue of metrics does seem to be, when you are talking about funding for performance, key. At the same time, you mentioned that SCAG report which was identified their own metrics. What are some of the metrics you would use?

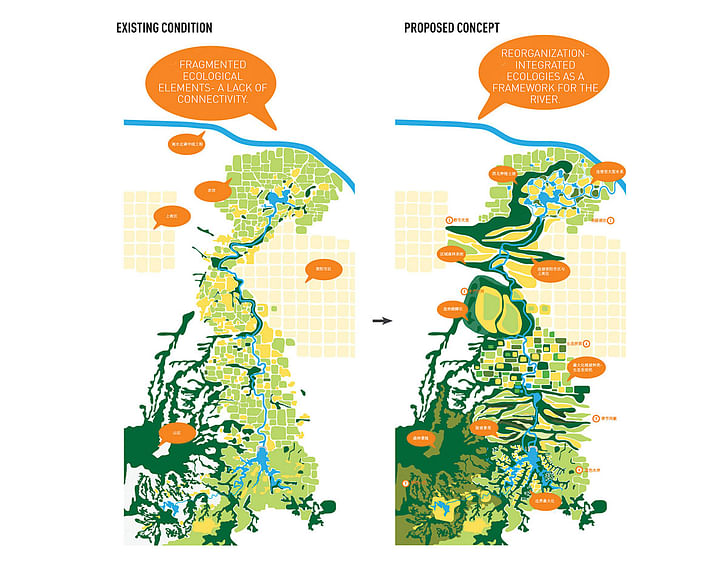

Gerdo- The metric we begin with is 'what are the latent ecologies of that area, and can we bring them to the foreground?' That is number one. From that, you bridge off into different types of ecologies.

On another track, are metrics related to human well being. Lifestyle, access, just access. To an open space. Do people get there by bicycle? Public transit, bus, light-rail. That in itself - lifestyle, human well being - has its branching of possibilities.

Then another track is definitely performance driven metrics. If you have to deal with stormwater, how much water can it hold? How much water can we reuse. Do we plant enough of the right type of tree (broadleaf vs. shortleaf) for carbon sequestration? Those are the kind of metrics of interest to me when trying to justify a park. Or define what a park is.

Nam- Given the contemporary realities these sorts of projects have to accept, what is the tension between the historic reality and the post-industrial freak-ology. Is the goal to return to a sort of pastoral, original condition?

Gerdo- Well I think that tension is exactly where we are. In this firm, in my studios. We want to position ourselves right where that tension is. We don't want to recreate or even ignore the pastoral image. We want to acknowledge though contemporary society, which has its own needs. Separate from nature. Our projects are right in the middle of that.

Nam- That edge or nexus, leads me to think of a suture. Looking for instance at SWA’s Buffalo Bayou project, you are almost literally right on an edge. Between the river and the freeways. Thus, two historical conditions with the project right in the middle.

Gerdo- Yeah, nexus is a good word. The Bayou for instance. Through design and creative intervention, people visit and want to return to that corridor. Which is an good measure/metric. Many projects solve all the problems, but nobody wants to be there. I think the distinction lies in how it is thoughtfully designed, how program is considered, how the materials are used.

Nam- We have mentioned programming a few times now. Can the designer's role extend beyond occupancy in terms of programming? There seems to be with many of these sorts of projects the need to ensure an 'audience.'. Does that happen organically? Or with these projects, is it a case of 'if you build it, they will come?'

Gerdo- Well, in architecture you have the Bilboa effect. With landscape however, it is a more difficult challenge. You can't make something in a vacuum and expect people to visit, appreciate it and return. Return visitation is key in understanding what a landscape wants to be. This is why community process is key. Firm-wide with all of our work, that involves public realm open space, the public process, the community outreach process is intense. To be really innovative in that process is number one difficult and number two, requires some real vision. To not allow design to be compromised or watered down. Landscape architects and urban designers are at the fore front of that process.

Nam- Sometimes you hear designers, who have done projects in China or elsewhere - where it is easy to drive a project through - contrast their experience with the situation in the USA. Here you have to worry about NIMBYism, the public process, all of which may delay or otherwise impact the project. Yet, you are actually saying that is a condition to embrace?

Gerdo- Absolutely! You have to not just embrace but master the public process. If you don't, you end up with vanilla.

I want to build projects using real metrics, a real public process-driven idea. That is what will allow these sorts of projects to grow, change and be catalytic. Within an urban context.

For me that is what is exciting about this, about landscape architecture. It never ends. These landscapes are highly dynamic. Moreover, the people I am working with in the public realm are young, hungry, wanting to make their mark on their city. They are looking for landscape architects that can master the public process and create interesting design.

Nam- I have two final issues I would like you to respond to. The first is that I have heard and read where some architects, urban designers or planners have viewed the rise of landscape architecture, or landscape urbanism, as almost a coup. An encroachment on their discipline even. Yet, many projects even in academic studios, seem to be pursuing a more cross-or-inter-disciplinary model or practice.

Gerdo- Alot of what is being taught in schools is about trying to tackle ambiguous sites. It is unclear, can't draw a box around it. It is basically an area, here are some issues. The demand is coming from the public agencies we work with. These people are coming to me and saying what about the ecologies of this area. Most of them are young and smart! They want to know about the natural systems and ask about how they can get funding for implementing sustainability metrics. They need consultants to help them utilize the funding that is available by identifying those systems.

Nam- In terms of how to address this sort of undefined, complexity, there is a move towards cross-disciplinary studios in academia. Professionally, you find mergers like the AECOM/EDAW move or other big consulting firms offering total service delivery. Is this being driven by the scale and temporal, systemic approach?

Gerdo- Absolutely! Universities all around the world are doing this. What makes interdisciplinary collaboration different today, is how the issues are framed and where the sources of funding come from. I should be clear, it is just not happening enough. Where you have a studio with; landscape architect, architect, urban planning, real estate development or economics students all together.

Nam- Finally, your book, the title talks about landscape infrastructure(s). Is that a subset of landscape urbanism? Is there a useful distinction to make there?

Gerdo- Landscape infrastructure is directly tied to, and is a subset of, landscape urbanism in the sense that it examines a specific system like right-of-ways, corridors, green roofs, etc, within the broader context of urban landscape. It is not so much about a new or redesigned urban region as much as a more efficient use of existing systems. Making those systems more productive. For example, here in Los Angeles, the Tehachapi transmission corridor brings clean energy to the City via wind turbines in the Mojave Desert. With over 100 miles of corridor, this infrastructural system is tied to the city yet also approaches the mega-regional scale in terms of its potential role as a viable landscape that can benefit people and nature.

Parks in the making...

I began this piece with a couple of questions, including: How can parks be developed to serve as an infrastructure(s), and whether a park can be more than a park? The preceding discussion offers a landscape architect's perspective on both these questions. Infrastructural systems should always be multi-use. A park must therefore expand the traditional concept of park-land. This can be accomplished through layering. Of program, systems and owner(s) or user(s). Multiple constituencies or agencies allow for pluralistic funding sources. Moreover, as Gerdo makes clear, the process must be open and community centered. The community, however defined, is the source of legitimacy or revenue. Parks thus represent a nexus and creative corridor. Shaped by the community process which drives and delivers a narrative. Through this narrative, the design extends beyond occupancy into post-programming. This sort of temporal process ultimately is perhaps the most important factor in determining the success of landscape architecture and park space. Whether top down (government or market driven) or bottom up (organic, localized and civic based) creation.

Of course there are potential downsides. I recently read, “Most of the urban projects we would love to see implemented sound a hell of a lot more plausible when pushed by a politician or lobbyist, with some solid PR backing." If so, should we not wonder if agency can no longer be "attained through design solutions anymore"? Does a successful project come down more to marketing or branding than design? What exactly is being designed? Systems, a concept, or a place? Within this context, it should be noted that some have begun to re-conceive of the need for a more soft approach to design. For, instance, the recent call for papers from Bracket 2: Goes Soft. What kind of designer works within this less physical medium? A recently completed reading of Kazys Varnelis's Infrastructural City suggests the appropriate notion may come from the field of software development. Namely, the hack/jam. Gerdo, at one point in our conversation, noted "Landscape urbanism is also about focusing on a specific kind of urban condition and dealing with all these associated problems". In such a case, a park becomes little more than a tool through which much larger and more systemic problems are addressed. In my view, his belief in the community process is a real statement about the possibilities for landscape infrastructure in this country. Specifically, because it points the way forward for those interested in concepts like social design, the 'right to the city' or infrastructural ecologies.

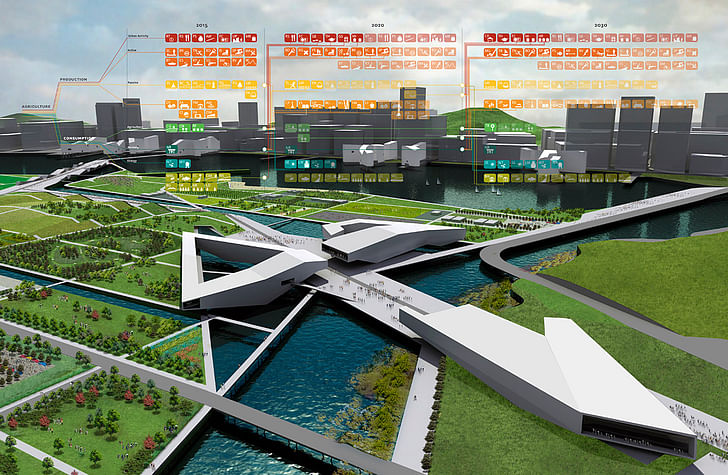

Finally, two brief reflections. Both related to the concept of parks, as infrastructure and act of social design. I have loved the work of Turenscape since I came across it first a few years back. In a recent interview discussing their Architectural University in Shenyang project, an important point was made. Regarding the ability of the park-landscape to integrate the role of the community in the design process. But more important is the process, the time, the cycles, the harvesting, the planting, the whole process is the landscape. ...In a culture of landscape-process, the landscape becomes a protagonist in the story, it takes on identity. The projects, involvement of the students in a seasonal act of harvesting the rice, suggests a way for the designer not only to design a park but also an infrastructure for social design. Such labor/ritual is a way to create cultural capital. Although, there would obviously be issues of scaling and cultural variation such a model also suggests a methodology for overcoming concerns of post-occupancy, long term maintenance. As for instance Gerdo's concern over "blow and go". I also recently came across a press release about how Planters Co. (of peanuts fame) was planning a viral campaign of sorts. Which would seek to distribute a number of Planters branded "pocket parks" across a handful of, surely in need, American cities. Is such a model of park development better than no park at all? Does it represent the perfect public-private partnership? Could those parks ever be truly public landscapes? Some might say yes, others may just be thankful for the green-space. Surely both can agree that more, not less community involvement in the design process will make or not, the projects success.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.

An ex-liberal arts student now in healthcare informatics, I am a friend of architects and lover of design. My interests include: learning/teaching, religion(s), sustainable ecologics/ies, technology and urban(isms). I was raised in NYC, but after almost two decades of living in North Florida I ...

1 Comment

Was reading Brian Eno's discussion in Guardian with radical economist Ha-Joon Chang, and this from Eno jumped out

"What is the value of a park? You can't quantify it. We keep them because we've inherited them. But I'm sure there'll be a rightwing movement in the future that says, "Parks? What are they for? People just wander about in them – and there's dog shit all over the place. What's the point of that? A great big piece of real estate in the middle of London that could be generating income – we can quantify that." Quantification is a big temptation for society because it looks like control."

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.