As our recent Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence series demonstrated, AI will inevitably play a sizeable role in the future of the architectural profession. For architecture schools tasked with equipping students for the future of practice, the advent of AI poses significant challenges.

How do faculties account for the fast pace of innovation in AI when structuring years-long curricula? How can students from architectural backgrounds be introduced to AI through media and methods that feel relevant to their future careers? How do schools balance an existing obligation to train architects in the delivery of physical buildings with new commercial possibilities created by AI, which may stretch beyond the architect's typical domain?

To explore these questions in greater depth, we speak with Joseph Choma, Director of Florida Atlantic University's School of Architecture; a department that recently developed and launched one of the nation's first architecture programs requiring students to learn AI at an advanced level.

In November 2023, I interviewed UCLA’s Natasha Sandmeier as part of the Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence series. Among the many lines of inquiry in our conversation, grounded in Sandmeier’s work at UCLA Architecture and Urban Design’s Entertainment Studio, one reflection stands out with eight months of hindsight.

“Whenever these major technological shifts occur, we as educators always have to re-examine what we are assessing,” Sandmeier told me when I asked her advice for other academics looking to teach AI to students. “What are our criteria? Are we applying criteria that were relevant in a prior age that has passed? If so, it is vital for us to develop a new set of criteria, which may even involve collaborating with students.”

When I think back to my own experience in architecture school, representative of most across Europe and North America, I’m reminded of how much of our curriculum was built on settled precedent. We learned about architectural movements and styles stretching back hundreds of years. We studied an array of theories by (mostly dormant) groups and buildings by (mostly dead) architects whose contributions to the field were firmly established. Even the fresher aspects of our curriculum, such as software and building technology, were influenced by existing industry practices and the expectations of employers beyond architecture school.

Faculties that ignore AI run the risk of placing students at the same competitive disadvantage as did faculties of the 80s and 90s who ignored computers.

AI ticks none of these boxes. There are no centuries-long styles or movements to draw upon. Its theories are not dormant. In fact, some of the earliest adopters of AI and computation in the architectural space are still very much alive. There are few existing established industry practices on AI in architecture and, for now, few expectations from employers.

For architecture faculties, the challenges don’t end there. In addition to a lack of historical precedents, a large question mark hangs over even the near-term future of AI. Today, we are in the midst of an AI arms race playing out not only among nation-states but among established tech companies fighting to retain dominance and venture-backed startups fighting to topple them. This environment breeds not only an acceleration in technological advancement but also a culture of secrecy and confidentiality between and among the main players. We, the public, have no idea where this arms race will take us, even by the end of the decade.

It is from this set of challenges and obscurities that Sandmeier’s call to re-examine academic norms arises. Faculties that ignore AI run the risk of placing students at the same competitive disadvantage as did faculties of the 80s and 90s who ignored computers. Meanwhile, those who transplant AI into an existing curriculum not designed for such a new, fast-moving field run the risk of, in Sandmeier’s words, “applying criteria that were relevant in a prior age that has passed.”

So, how do we teach AI?

For Joseph Choma, Director of Florida Atlantic University’s School of Architecture, the need to teach AI is part of an “ethical obligation to prepare students not just for professional practice but for the future of professional practice.” In a recent conversation on the topic, Choma offered me an insight into his school’s approach, which, in fall 2022, saw it become one of the first schools of architecture to require all undergraduate students to learn AI at an advanced level. Last month, meanwhile, the initiative saw Choma and FAU honored as winners of the Innovation in AI and Technology Integration category for the Tambellini Future Campus Award.

“We realized we were going to have to figure out how to integrate AI,” Choma told me. “We can’t just insert it into the program as one course but really have to look at our whole curriculum.”

Choma offered me an overview of how AI has been woven into each stage of FAU’s five-year Bachelor of Architecture program; a journey which Choma also unpacked in a recent conversation with Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence contributor Neil Leach. In particular, we dwelled on two specific aspects of the course that newcomers to AI in architecture may not have expected.

The first aspect centers on the relationship between analog and digital processes. While students beginning a course on AI may expect to find themselves grounded in digital processes from day one, students at FAU are just as likely to find themselves folding paper by hand, making models with sticks, or drawing elliptical shapes with pins and strings. As Choma explains, one of the primary goals of the first three years of the course is to “use the analog as a means to demystify the digital;” to instill in students an appreciation for computational thinking and making using familiar means, and to understand design constraints as opportunities.

The distinction between making the rules to make the drawing, versus just making the drawing, is important to understand when we are preparing students for AI. — Joseph Choma

“We think differently when we are folding paper, writing an algorithm, making a model, drawing by hand, or collaborating with an AI,” Choma told me. “They are all valuable. I don’t think that just because new tools are being added, the others get erased.”

Choma cites one exercise from Year One of the course, where students use pins, strings, and pens to generate elliptical shapes. As the length of the string or location of the pin is changed, elliptical shapes are layered upon one another in what Choma describes as an “analog parametric model,” whose variations incrementally reveal a drawing less like a series of layered two-dimensional shapes and more like a three-dimensional space.

“It teaches students to see beyond that which is there and looks at representational abstractions,” Choma told me. “It is very much computation even though they are not using a computer. The distinction between making the rules to make the drawing, versus just making the drawing, is important to understand when we are preparing students for AI.”

This exercise in bridging physical and digital realms extends beyond the analog work of students and into the built environment. Like in any architecture school, FAU students engage with instructive architectural precedents throughout history, whether it be centuries-old villas by Palladio or contemporary pavilions by Brooks + Scarpa. However, FAU students are encouraged to break from the conventional lens through which such buildings are studied and instead analyze precedents in ways more relevant to AI, be it reading floor plans of a series of operations and ‘shape grammars’ or understanding architectural drawings not as static images but as a series of rules open to codification and reconfiguration.

It is not just about how we train AI models, but how we create collaboration between them. — Joseph Choma

Across the fourth and fifth years of the program, students are introduced to AI at an advanced level, grounded in staples of AI processes such as algorithms, 3D data sets, and self-organizing mapping. Here, we encounter the second unexpected aspect of the FAU course, at least in the eyes of AI newcomers. While some students in the course find themselves designing buildings, others design processes and workflows. Data sets and algorithms are not only the inputs for a creative project but also the output.

“There is a fundamental difference between designing a workflow versus designing a building,” Choma told me. “With regard to workflows, my colleague Daniel Bolojan believes that the future will contain thousands of AI models, not one super AI. One of the roles of the architect will be to create a web or network to connect the AIs together. It is not just about how we train AI models, but how we create collaboration between them.”

Positioning architects as the designers of a process, workflow, or system opens up a new world of commercial opportunities in the age of AI. As Choma notes, however, architects are already versed in workflow design for physical structures, most prominently by overseeing an interdisciplinary project team from structural and mechanical engineers to landscape and interior designers. “When you build interdisciplinary collaborations, it is not about imagining the final end product,” Choma shared. “It is about understanding what each role is, how they intersect, and how we use this network to deliver something we could not deliver without each other.”

This act of encouraging students to think about the design of processes and products, as well as analog and digital modes, is not just about making AI accessible to students. It is also a recognition by Choma and his colleagues that while AI will undoubtedly play a role in the future of the profession, it does not negate nor diminish the existing responsibilities that architects have to the built environments, nor those that architecture schools have to train those architects.

I’m interested in how the normative starts to embed more innovative research, and how the projective starts to be grounded in more normative constraints. — Joseph Choma

“As a school, we cannot bias the product or process over one another,” Choma told me. “We are still training professional architects, who need to know how to design and deliver comprehensive buildings. But we also have to start teaching them innovative research methods. Sometimes, such methods can become speculative, visionary, or even science fiction. But I’m not interested in the purely projective or the purely normative; I’m interested in how the normative starts to embed more innovative research, and how the projective starts to be grounded in more normative constraints. If students are exposed to both during their education, they will be better equipped to figure this out.”

The importance Choma and his colleagues place on research methods is demonstrated by physical changes taking place on FAU’s Fort Lauderdale campus. Chief among these is the Creative AI Lab, a new laboratory equipped with a 180-degree projection screen, eight 3D scanners, AR and VR equipment, and a giant Nvidia server. Led by Assistant Professor Daniel Bolojan, the lab allows students to digitize physical models for manipulation and AI integration. “AI will be able to give you a new range of possibilities, then isolate one of those possibilities, give it to your goggles, and suggest how you might want to change your next design iteration physically,” Choma told me.

We need to keep iterating, and we cannot be fearful of the unknown. A school of architecture should always be a work in progress. — Joseph Choma

As our conversation concluded, I asked Choma what advice he would give to other schools of architecture interested in teaching AI. “In my opinion, a school of architecture is a design project,” Choma noted. “We need to keep iterating, and we cannot be fearful of the unknown. A school of architecture should always be a work in progress. That perspective is what allowed our faculty to buy into the idea of changing our curriculum to accommodate AI.”

“I would say for schools of architecture that may or may not have experts in AI, that doesn't mean you can't teach students about systems,” Choma added. “Ask how you can get students to understand the difference between designing products and designing rules, logic, systems, and workflows, even in an analog way without using AI. To me, that is a much better foundation for preparing students for the future of architectural practice rather than only introducing them to AI tools as end users.”

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

1 Comment

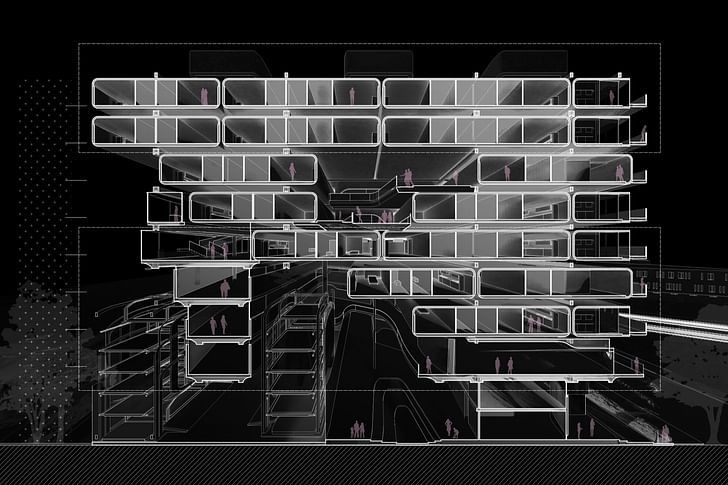

I fully agree that there is an “ethical obligation to prepare students for professional practice”, but the time to learn how to design is limited, and from the examples shown, what students are producing seems to have little connection to the work they will ultimately do.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.