Across the globe, the design and construction of affordable housing is failing to meet demand, leaving both low and middle income dwellers with little choice but to accept high costs, substandard conditions, or a move away from urban centers. This reality not only presents dangerous environmental and social conditions, but also underpins a fundamental failure of our current processes to design and construct quality affordable housing. In the face of this crisis, architects are finding opportunities for change. In this article, we speak with architect David Wallance FAIA, whose new book The Future of Modular Architecture sets out a paradigm-shift vision for the future of affordable housing. Here, we discuss the details of Wallance’s industrial-scale system, derived from the standard dimensions of intermodal shipping units, as well as the major changes such a system would bring to cities, housing markets, the environment, architectural education, and the business structure of the architectural profession.

The construction start-up company Katerra was a trailblazer, until it wasn’t. The Silicon Valley venture was launched in 2015, seeking to streamline the entire construction process through a comprehensive design-build model, encompassing everything from architectural design to manufacture and installation. Katerra’s “one-stop shop” for the built environment included factories in Arizona and Washington making everything from mass timber structural elements to kitchen countertops, all dedicated to replacing the waste-laden construction process with a streamlined, integrated approach more akin to automobile production. At its height, Katerra was viewed as an exemplar for how design and construction could embrace the highly efficient, vertically integrated processes that underpin many successful industries. Ultimately, it was not to be. After six turbulent years, which saw both rapid expansions at its highs, and investor bailouts at its lows, Katerra finally folded in June 2021.

While Katerra’s alternative approach to construction ended in failure, the inception and media interest in the start-up was symptomatic of a wider desire among the architecture and construction industry to inject new ideas and business models into the design and fabrication of buildings. This desire is not without reason. In 2016, for instance, a report by McKinsey declared that the construction industry was “ripe for disruption,” noting that 20% of large projects are typically delivered late, and 80% delivered over budget. The report also posits that construction is not only less digitized that the automobile and technology sectors that it is frequently compared to, but is actually one of the least digitized in the entire economy. In McKinsey’s ranking of each economic sector’s embrace of digitization, “construction” is second from the bottom. Only “agriculture and hunting” was ranked lower.

“While the construction sector has been slow to adopt processes and technology innovations, there is also a continuing challenge when it comes to fixing the basics,” the report concludes. “Project planning, for example, remains uncoordinated between the office and the field, and is often done on paper. Contracts do not include incentives for risk sharing and innovation; performance management is inadequate, and supply-chain practices are still unsophisticated. The industry has not yet embraced new digital technologies that need up-front investment, even if the long-term benefits are significant.”

The opportunities for disruption within the construction industry can offer frustrated designers a path to renewed relevance and purpose.

McKinsey’s conclusion, though damning, can also be viewed as a source of optimism for architects. While reflections on the future of practice often center on fears of growing irrelevance, heralded by a doomsday cocktail of automation, insurance costs, and the fracturing of project roles once held by the architect, the opportunities for disruption within the construction industry can offer frustrated designers a path to renewed relevance and purpose. As we showed in our recent in-depth look at the architects designing software to combat climate change, and our ongoing Working Out Of The Box series, an architectural background presents an almost universal license to deviate, pivot, and innovate, whether within or beyond the architecture and construction industry. In the context of both climate and affordable housing crises, this exercise in rethinking established processes, and repositioning the architectural profession itself, can uncover new ways of addressing longstanding problems.

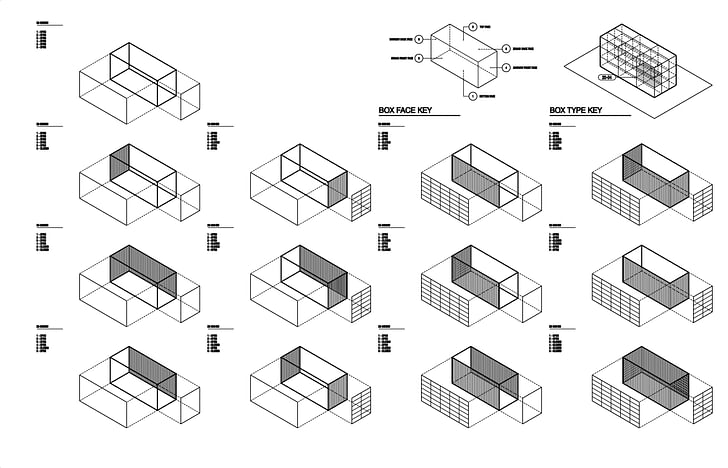

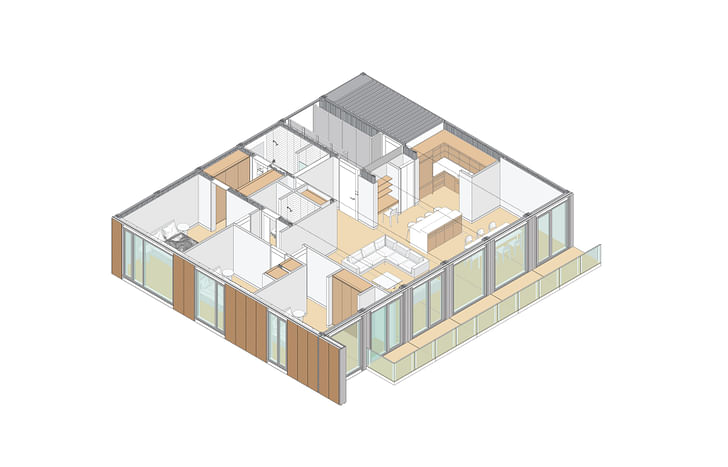

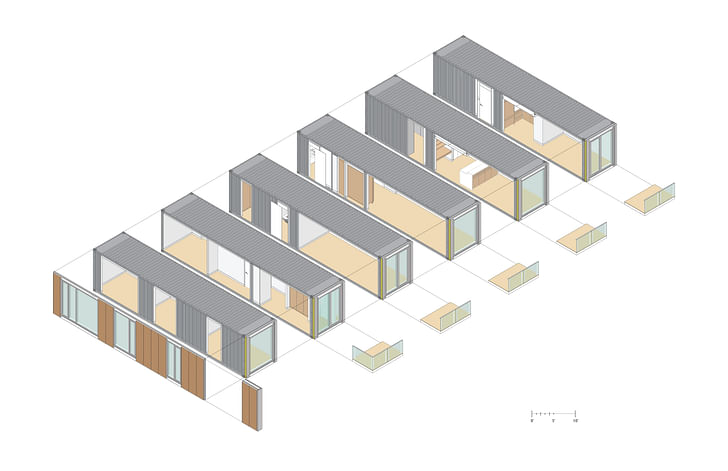

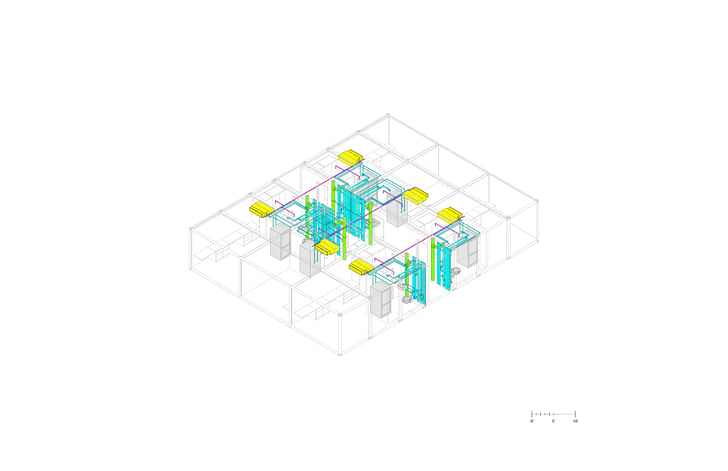

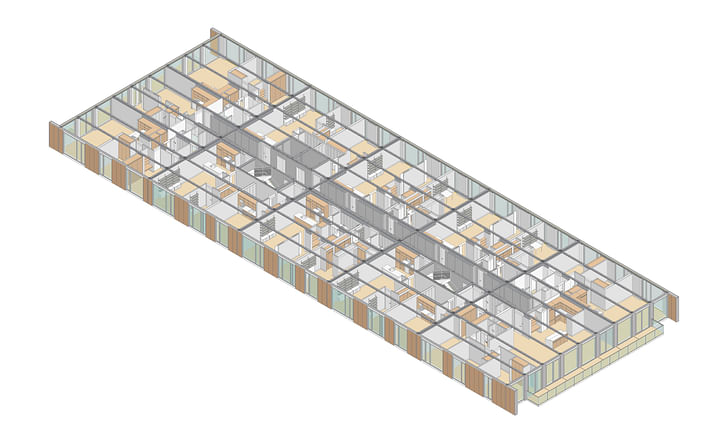

This ethos of shifting paradigms underpins the vision of David Wallance FAIA, a founder and architect at Brooklyn-based studio DRA/W, whose new book The Future of Modular Architecture puts forward an unprecedented proposal for the future of housing. Wallance, whose 40-year career as an architect has included 20 years teaching advanced building technology at Columbia GSAPP, has spent 15 years developing a next-generation system for mid-and high-rise modular architecture, one which is grounded in a fusion of globalization, equitable urbanism, and sustainable development. Central to Wallance’s vision is an open-source modular system, made up of individual components whose dimensions match those of intermodal shipping containers. This new “modular standard” unlocks the ability for individual units to be manufactured and distributed at an industrial scale, leveraging existing intermodal freight transport systems and global supply chains to create a highly-efficient, well-designed, affordable industrial product.

Wallance sees an opportunity not just to fundamentally change the nature of how we design and construct the housing of the future, but to also open radically new business structures for architects.

In shaping his vision for the future of modular architecture, Wallance sees an opportunity not just to fundamentally change the nature of how we design and construct the housing of the future, but to also open radically new business structures for architects, fusing notions of innovation, entrepreneurship, and industrial design. Speaking to Archinect about the book, and the broader vision it sets out, Wallance is clear that his “intermodal modular architecture” goes beyond innovating within our current construction system. “Innovation within construction has been rising in recent years; but what I’m calling for goes further,” Wallance explains. “I believe in a paradigm shift. This paradigm shift is more than just modular construction. Modular architecture has been around for over fifty years; it isn’t new. The paradigm shift I put forward is an open-source kit-of-parts-based system, spurring the collaborative growth of new ideas within a baseline framework, similar to how apps are developed that plug into a smartphone operating system. I believe in flexibility within standards. The smartphone operating system is a set of technical standards produced on an industrial scale, which is simultaneously open enough that third party app developers can do anything that they can dream of, as long as it plugs in seamlessly with the technology. I believe that intermodal modular architecture can bring this approach to cities globally.”

I don’t think we can even imagine the kind of adaptations and ideas that will occur in the future if this idea is widely adopted.

The design of any modular architecture system must find a balance between standardization and individualism; one which is rigid enough to allow cost-effective production on an industrial scale, but flexible enough to meet the needs of various localities, trends, and personalities. Reflecting on this balance, Wallance sees the discipline of a standard kit-of-parts as a platform for freedom and experimentation. “We have no desire for homogeneous housing across the world,” he says. “However, with the ability to differentiate within parameters, architects can begin designing and adapting regionally, climatically, culturally-specific components which still generate sufficient sales volumes to make them viable. For example, we could see façade adaptions to benefit hot, humid climates, and completely different adaptions for cold, northerly climates. Apartment layouts which are fitting for one culture or family arrangement may not be appropriate for another. By plugging into conventional standards, we unlock a freedom to adapt, shape, and evolve within those standards.”

Inside the parameters of an intermodal system, Wallance sees no cap on future adaptions. “With the right incentives, architects, industrial designers, product developers, and anybody who has the wherewithal to come up with an idea and get it manufactured can plug into the intermodal system, to create almost anything,” he says. “I don’t think we can even imagine the kind of adaptations and ideas that will occur in the future if this idea is widely adopted. We could see a future of architectural “hackers” who take this underlying hardware and ask, “what can I do with this system that has not been tried before?” "

The cost savings made possible from a mass-produced system would alter the nature of current funding model, taking the conversation away from value engineering of bespoke elements, and instead towards building forms which are rational, efficient, yet compliant with relevant local codes.

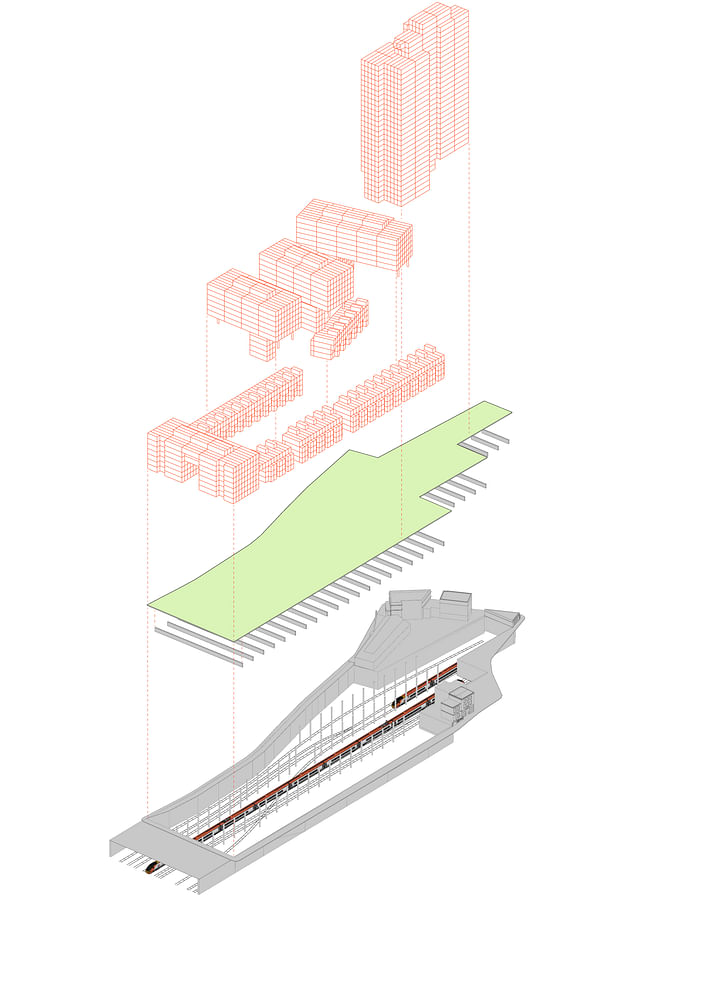

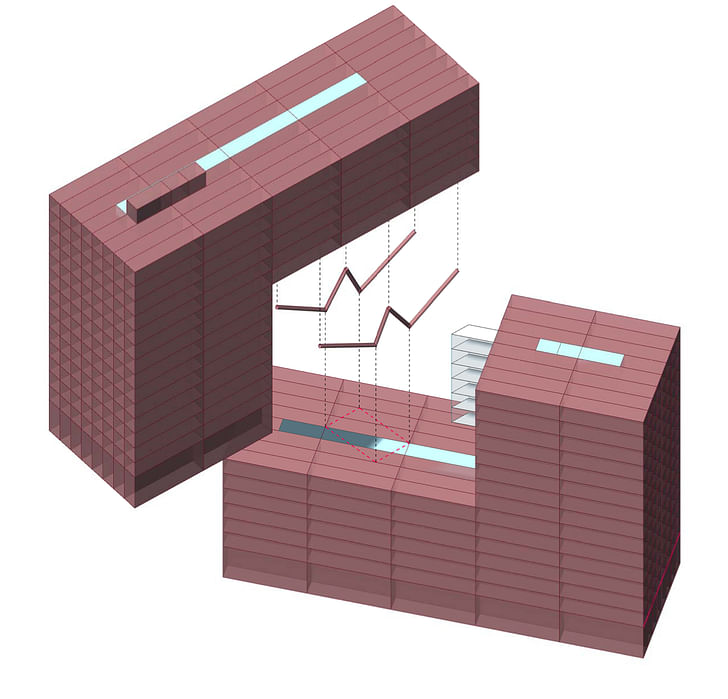

An emphasis on prefabricated, standardized building modules, and away from a heavily-localized, bespoke building product, also calls for a revaluation of the relationship between a building and its site. In many traditional design processes, the subject site holds a heavy influence over the resulting design proposal; not only because of an architectural drive for individualism, but also because of a client’s desire to maximize the financial potential of a site; a factor particularly prevalent in residential construction. Wallance frequently turns to a site-specific “podium” level (or levels) as a mediator between the ground plane below, and the modular system above. “In many of the feasibility studies and design competitions that we have done the solution is a mixed-use podium,” Wallance explains. “This creates an interesting design challenge that requires the architect to engage with the project from a local perspective. This podium is not something that can be imposed by a system, it comes from the ground up. It may even be the ground plane itself, as in the case of an infrastructure overbuild, or it could be ground floor retail or cultural space. The success of this intermediary element can make or break a project.” Such a move would not alleviate the pressures on the architect to deliver a scheme which generates value for the client. Rather, Wallance argues, the cost savings made possible from a mass-produced system would alter the nature of this model, taking the conversation away from value engineering of bespoke elements, and instead towards building forms which are rational, efficient, yet compliant with relevant local codes.

A move towards Wallance’s vision of an intermodal modular architecture would bring with it new business models for the architectural profession.

A move towards Wallance’s vision of an intermodal modular architecture would bring with it new business models for the architectural profession. These new models can be imagined as “forks in the road.” In the first instance, Wallance sees two defined “structures” of architecture firms; an “everyday architecture” studio which specializes in the design and delivery of the intermodal modular system, and an “atelier architecture” which oversees bespoke cultural and institutional buildings within the traditional studio environments familiar to many architects today. A circumstantial “fork” is also inferred between designers small and large, local and global. Within the delivery of the intermodal system, small, lean firms may gain the ability to deliver much larger projects than presently possible, given the removal of the technical depth needed to execute large projects. These local architects also gain the ability to use an understanding of regional climates, styles, and legislative frameworks to deliver the bespoke lower-level podiums discussed earlier. Meanwhile, Wallance sees his approach giving rise to an alternative business model for architects working on the intermodal system itself. “Some people within the traditional architecture firm will design projects that use the intermodal system,” Wallance explains. “However, others will develop, test, prototype, and roll out new product developments. Some will get entrepreneurial and develop apps that participate in a global supply chain to imagine new ways of living, or evolve and optimize current trends in how we live.”

An effective response to climate change must include a re-evaluation of how, and where, we live.

While Wallance’s proposal is undoubtedly a paradigm shift when compared against traditional housebuilding, the validity, or even necessity, of such a departure becomes clearer in the context of the climate crisis. “The single most effective climatic thing we can do is change our land use patterns, and attract people back to more vertical urban environments, with centralized, efficient infrastructures and access to mass transit,” says Wallance. While building-scale factors such as embodied carbon, energy efficiency, and building envelope performance also influence the impact of the built environment on the climate, Wallance argues that an effective response to climate change must include a re-evaluation of how, and where, we live. “Our current affordable housing crisis is driving people away from city centers into the suburbs, with catastrophic environmental consequences in terms of land use and automobile use,” he explains. “Even if we were to build net-zero suburbs, personal transportation would still create a significant environmental footprint. We need to attract people back into cities. In that sense, the goal of an intermodal modular architecture is to reduce the cost of housing to the point where people are attracted, and financially able, to live in cities again. This approach also has the potential to address affordable housing for both low-income and middle-income dwellers. Using an automobile analogy, we see how a standard chassis underlines both economy and luxury models of car. Similarly, a universal intermodal architecture can be suitable for low-income but also middle-income users; a segment which is often missing from the conversation about affordable housing.”

If the operation of Wallance’s proposal will require a paradigm shift within the industry, so too will its inception. With housing construction deeply entwined with a real estate market defined either by low risks or fast financial returns, Wallance’s proposal requires visionary, long-term investors willing to fund new ideas. “It’s going to require capital,” he explains. “My experience has been that real estate development capital is too project-focused to take on an R+D, prototyping, or testing enterprise. This idea will require patient capital.” Such funding would require architects to step away from traditional revenue streams derived from commercial clients, and instead look to investors within the private sector, or government support either in the form of industrial policy, or an injection of initial capital. As a cautionary example, however, Wallance points to the Lustron Corporation, who in 1947 received a Reconstruction Finance Corporation loan from the Federal Government to manufacture mass-produced prefabricated homes using innovative materials, assembly-line efficiency, and modular design. Despite this government support, or perhaps because of it, Lustron declared bankruptcy in 1950 when production delays and a poor distribution strategy caused the government to pull the plug on financing. Nonetheless, the Lustron homes, of which 2000 are still in existence across 36 U.S. states, serve as evidence that new ideas in construction, and market delivery of those ideas, are possible beyond traditional real estate revenue sources.

As architects, we need to engage with the means of production.

Drawing on his professional and academic career, Wallance sees potential for a new generation of architects to realize new ideas such as his. “As architects, we need to engage with the means of production,” Wallance explains. “One avenue to achieve this is for young architects to diversify their portfolios, and to merge traditional design services with other interests, such as start-up ventures that offer a product, whether tangible or software. If young architects can become involved in the process of raising capital, product development, marketing, and managing a sales process, in co-existence with traditional practice, we may see a shift in which power comes back to architects through engagement with the market, and commerce.” This reflection is also informed by Wallance’s own introduction into architecture. “My father was an industrial designer,” he adds. “Therefore, I grew up with an ethos where design was integrated with the process of production. These were not two separate disciplines. You had to understand how things were made, and design for the production process itself. It went beyond simply making something independently beautiful on a page, or as a model.”

Ultimately, the “fork in the road” which Wallance’s proposal would create in professional landscapes may be mirrored in education.

Wallance’s paradigm shift within the construction industry would also require a parallel paradigm shift within architectural education. “Architecture schools are not currently geared for educating architects in this kind of system-based, market-oriented approach,” he says. “What we need is actually closer to industrial design.” Citing the Stanford D School as a potential model to adopt, Wallance calls for a new curriculum that allows architecture students to access a cross-disciplinary education portfolio, while still being educated in the fundamentals and histories of architecture. Ultimately, the “fork in the road” which Wallance’s proposal would create in professional landscapes may be mirrored in education; where a specialization in architecture as craft, artefact, and individual, is matched by an education adjacent to industrial design, where architecture is framed as an industrial product.

“At Columbia, I taught advanced building technology,” Wallance reflects. “Students seemed hungry for the kind of experience I was offering them; a grounding in the way buildings are assembled. I also taught a modular course in which students learned that there was a critical need for a new approach to housing. I believe the ground is prepared. This is something that young architects are receptive to. It could really be the beginning of a shift.”

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

8 Comments

I do not agree with the broad need for people to return to cities. There are problems beyond housing in cities that more crowding will not solve. The rest of the article is interesting, but the ship of state is not going in that direction. A major quake would have to occur. Covid was a shake up, leading to the city exodus. I do support the intent and wish the Elon of housing was in the horizon.

city exodus? where's the data to back this up? nyc is still looking pretty lively from my window..

It will work this time I swear.....#Atlantic yards....

Add Katerra' bankruptcy too.

Katerra wasn't about housing, it was about money. If it was about housing it would have been entirely different - and likely successful at least in some regards.

there's a much easier way to address the affordable housing crisis, which is through its funding sources (or lack thereof). technological fixes always over promise and fail to deliver.

Ah yes, shipping containers. The oft discussed but rarely/never built panacea for every problem the built environment has faced in the last century.

Where did you get shipping containers? I see a reference to the dimensions of shipping containers, but these aren't that.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.