The 21st century has seen rapid advances in technology, allowing an ever-increasing portion of the architectural and urban planning process to move into digital space. At the same time, our understanding of the climate crisis and momentum to address it have also gathered pace. Responding to both technological advances and climate awareness, architects and designers have begun to embrace software not just as users, but as creators. To explore this further, we speak with four architecture and design studios who are developing digital tools that respond to the climate crisis. From BIM software plug-ins and carbon calculators to interactive tools that generate location-specific environmental design strategies, these four teams are carving a potential future path for the profession; one with responsibility for the design of both digital and physical systems.

If you were to ask a member of the public “what does an architect do?” the response would likely be a variation of “they design buildings.” In some cases, this answer may expand to encompass the vast range of scales that architects operate at, from bespoke fixtures in an individual room to a masterplanned metropolis. The conventional understanding of the architect’s role is nonetheless grounded in notions of shelter, structure, and occupied space; themes which run through our education, institutions, and public perception.

One of the strongest accolades of an architectural background, however, is the ability to transcend this convention. As we often show through our Working Out Of The Box series, the skills acquired through architectural training give license to explore an endless list of topics, be it perfume, textiles, music, or extra-terrestrial life. This flexible application of knowledge and ideas is of particular value at a time when the world grapples with a climate crisis; one that requires us all to step outside the silos of industry, and instead understand the world as a series of interconnected nodes and flows, currently feeding off each other to sustain an unsustainable system.

Architects and designers are becoming not only users but also creators of digital tools.

Given the impact of both the construction and operation of the built environment on the climate, architects are increasingly seeking ways to broaden their own ability to effect positive change. In a profession deeply associated with physical space, some designers are seeking solutions by going digital. Capitalizing on the increasing digitization of the design process itself, where data tools and software have become indispensable, architects and designers are becoming not only users but also creators of digital tools.

To further explore this phenomenon, we spoke with four architecture and design studios who have led the development of software aimed at addressing the climate crisis. Each of the four digital tools offers unique background stories, functions, aims, and users. While KieranTimberlake’s Tally system plugs into BIM software to generate Life Cycle Assessments, SOUR Studio’s carbon calculator offers a standalone resource for architects to understand the embodied carbon behind their designs. While CallisonRTKL’s CLIMATESCOUT tool offers a portfolio of sustainable design strategies for new buildings, Sasaki’s climate.park.change allows designers, agencies, and the general public to understand and combat the specific issues facing America’s natural parks.

Despite this variety in approach and function, all four tools speak to an inter-relationship between the physical and virtual; a demonstration of how digital tools can offer unprecedented detail, accuracy, and ease of access to knowledge of how design decisions can have a positive or negative impact on the environment. Moreover, all four speak to a growing recognition that while the future of the architectural profession will continue to be grounded in the convention of building design, our ability to tackle major issues and crises reaches much further.

Technology that interacts with AEC professionals and enables them to access the transparent data they need has the potential to catapult things forward.

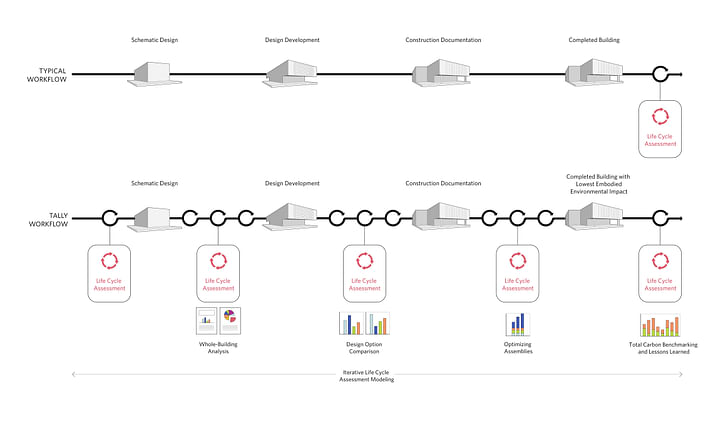

In recent years, Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs) have become a prominent mechanism for measuring a building’s energy use and environmental impact from schematic design and construction through operation and demolition. In 2008, when architecture firm KieranTimberlake recognized the difficulty in quantifying the environmental impacts of building materials within a fast-moving design process, they set out to solve the issue themselves. The result was Tally, an industry-renowned LCA tool that links with Revit software to enable Life Cycle Assessments on-demand.

“We immediately recognized this as an interdisciplinary challenge, and we were well-positioned to tackle it,” says Billie Faircloth, FAIA Partner and Research Director of KieranTimberlake. “Tally was created entirely in-house by members of KieranTimberlake’s Research Group. Our ‘Tally Team’ had backgrounds in urban ecology, industrial ecology, environmental management, architectural design, detailing, and app development, and lent their respective expertise in LCA modeling, architectural design, graphic design, BIM modeling, and coding to inform the software’s development and evolution.”

In developing Tally, KieranTimberlake’s team built upon their predisposed knowledge of architectural modeling conventions and specifications to knit the processes of BIM and LCAs together, ensuring a final interface that was familiar and accessible to BIM users. “We also required Life Cycle Assessment expertise outside our domain,” says Ryan Welch, who works at KieranTimberlake alongside Faircloth. “We found great support from Autodesk’s Sustainability Solutions group, which provided Revit software development training and listening sessions to help connect us with potential data partners. This ultimately led to our partnering with thinkstep/sphera (then PE International), who provided the LCA modeling underlying all the materials in Tally’s database.”

Following its launch in 2013, the Tally ecosystem has grown further beyond its roots as an LCA measurement tool. “The more we internally tested the potential of Tally, the more we understood it as a tool that allows our industry to take climate action,” says Faircloth. “In the eight years since we released Tally to the public, we’ve also realized that more than just providing an LCA tool, we needed to provide a steady stream of educational support such as training, speaking engagements, and webinars, to socialize across the AEC industry what was, at the time, a nascent modeling practice.”

The more we internally tested the potential of Tally, the more we understood it as a tool that allows our industry to take climate action.

Today, Tally is in the process of being transferred from KieranTimberlake to Building Transparency, a nonprofit dedicated to providing open-access data and tools that enable the building industry to understand and address the role of embodied carbon in climate change. “Technology that interacts with AEC professionals and enables them to access the transparent data they need has the potential to catapult things forward in terms of adoption and alignment,” says Stacy Smedley, Chair and Executive Director at Building Transparency.

Reflecting on Tally, Smedley is optimistic about a future where climate tools are free or affordable enough to allow accessible, fast, informative data for designing against climate change: “We are deep in the process of understanding what current Tally users love about the software in its current form, and what they would like to see in terms of additions, enhancements, or modifications. We are also mission-driven and are eager to move Tally into alignment with Building Transparency's mission of free, open-access tools and data to actionably reduce the built environment's impact on climate change.”

If everyday people demand a sustainable, healthy, inclusive environment, that will be the biggest catalyst for the industry to improve and innovate.

While Tally serves as an integrated tool for BIM software, SOUR Studio’s web-based Carbon Calculator uses interactive input and output figures to measure a building’s embodied carbon footprint. The studio, based between New York City and Istanbul, created the tool to gain a better understanding of the overall carbon footprint of their projects, both on-site and within supply chains. In response to a lack of interactive, accessible tools for generating such information, SOUR ultimately opted to make the software public and free for use. Like Tally, SOUR’s software came to fruition through a team of diverse disciplines. “Innovation is only possible with the collaboration of diverse experts,” says Pinar Guvenc, Partner at SOUR. “We co-created the calculator with the sustainability expert Alice Roberts, by building formulas around carbon emissions related to construction methods, land, building materials, and means of transportation."

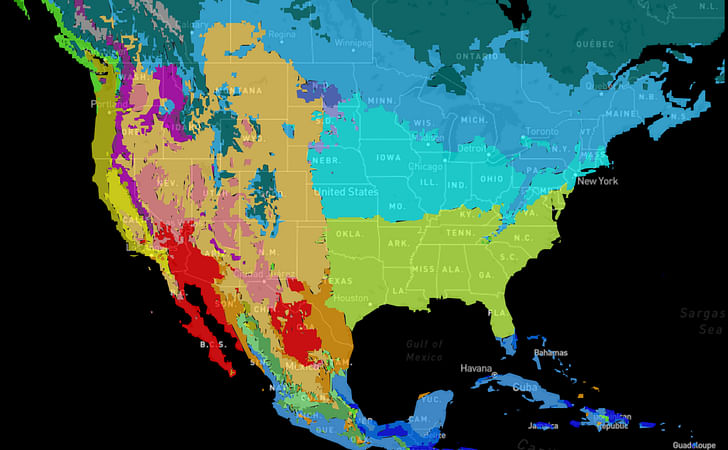

As the user inputs basic figures on size, area, location, landscape, and material sources, SOUR’s carbon calculator draws on data from the Carbon Leadership Forum’s Embodied Carbon Benchmark Database, European standards on environmental performance calculation, and extensive mapping of soil carbon stocks across North America. Using these sources, the tool measures the greenhouse gas emissions of a project in terms of carbon dioxide equivalency (C02e). “The Carbon Calculator will be an ever-evolving product, continually updated as we gain more data and identify new sources of carbon emissions that we need to account for,” says Guvenc. “Carbon Calculator is the first tool that we made public, but it won't be the last. As we continually rethink and innovate in our own processes, we will publish more and more tools and templates that address social and urban problems.”

As architecture studios, we need to be more proactive in addressing social and environmental issues relating to our built environment. That starts with a deeper understanding of those issues and how our projects contribute to them.

To Guvenc, SOUR’s Carbon Calculator is also a response to a lack of innovation within the industry, which is slow to address its environmental impact in comparison to others. “We see innovation in real estate far less compared to industries like health and technology,” says Guvenc. “Progress in the built environment is slow, or it's inequitable. As architecture studios, we need to be more proactive in addressing social and environmental issues relating to our built environment. That starts with a deeper understanding of those issues and how our projects contribute to them.”

For SOUR, their carbon calculator offers one avenue for this deeper understanding, where interactive software and tools can quantify architecture’s impact on carbon emissions. Guvenc is optimistic for a future where tools and software become integral to design decisions from the beginning of the process, championing sustainability, resiliency, and inclusivity. “As such tools educate the architecture community, we'll see more positive outcomes in the industry in terms of client decisions, responsive policy/zoning, and end-user awareness,” says Guvenc. “There will always be supply if there is demand, and if everyday people demand a sustainable, healthy, inclusive environment, that will be the biggest catalyst for the industry to improve and innovate.”

Understanding climate is one of the critical first steps in the design process of any building.

In addition to developing analysis-based software such as Tally and the SOUR Carbon Calculator, architects are also using interactive apps to generate climate-conscious design strategies for a given climate. One such app is CLIMATESCOUT, created by global architecture firm CallisonRTKL. The app merges data from the Köppen-Geiger climate classification system with 27 design strategies taken from the Architecture 2030 palette for sustainable design, allowing users to generate a building cross-section that overlays sustainable design characteristics appropriate for their selected location.

“Understanding climate is one of the critical first steps in the design process of any building,” explains Pablo La Roche, Principal and Sustainable Design Lead at CallisonRTKL. “Tools that aid in understanding climate and the selection and implementation of appropriate design strategies will then aid in developing more resilient buildings with a reduced carbon footprint. This was previously done with books that illustrated climate strategies. Today, climate analysis apps like this one offer a more effective way to do this. We wanted to create a free, easy-to-use tool that was useful not only to CallisonRTKL, but to the profession in general: students, clients, and even to people beyond the profession.”

The design of CLIMATESCOUT was architect-led, shaped by a coalition of CallisonRTKL’s designers, graphic designers, and computer programmers. A visually engaging experience was an important pillar of CLIMATESCOUT’s design. “Designers are visual thinkers and can work on the design of the project section interactively with the CLIMATE SCOUT section,” says La Roche. “By combining climate, data, and images, our tool connects climate with architecture to help users create better-performing and more responsive buildings. The app also provides condensed information on the strategy by clicking on the strategy icon and directly links to the Architecture 2030’s Palette with even more information and examples.”

Like the teams behind Tally and the SOUR Carbon Calculator, CallisonRTKL sees CLIMATSCOUT as an ongoing project, rather than a finished product. In addition to a possible expansion into areas such as embodied carbon, the team is planning on developing the current interface with more information on design strategies. “We would like to add a feature that indicates the effectiveness of selected strategies in different climates,” says La Roche. “This effectiveness could be measured in the ability to reduce GHG emissions, to provide thermal comfort, or to reduce energy use. We will also include an ability to export the final image with the strategies and directly integrate in reports, and an ability to export animations with the strategies.”

Creating an accessible tool was fundamental for us.

As CallisonRTKL continues to build CLIMATESCOUT as a resource for climate strategies in buildings, fellow international design studio Sasaki is taking a similar approach on an infrastructural level. With climate.park.change, Sasaki has developed an interactive tool which allows parkland operators and users to understand the environmental dangers facing America’s parks, and develop strategies in response. Using an interactive map, users can navigate to their preferred region (currently focused on selected western states of the USA) to understand the various climate issues for parklands in that region. Users are then offered a portfolio of strategies tailored for specific geographies, as well as three case studies demonstrating how the toolkit can be used to identify and tackle these issues.

To develop the tool, Sasaki partnered with the National Recreation and Park Association (NRPA). Through engagements with the NRPA’s Innovation Lab in Miami, Florida, the team noted that the national discourse on infrastructure and parkland resiliency against climate change was focused heavily on coastal systems. “Only ten percent of our land is on the coast,” says Anna Cawrse, landscape architect at Sasaki and one of the tool’s creators. “There was a need to translate this great work on coastal strategies to inland areas. Together with the NRPA we set out on creating a toolkit starting at the Intermountain West, an area of the country that was missing from the discourse.” Working with Sasaki’s internal mix of ecologists, civil engineers, urban designers, and landscape architects, the team embarked on developing an accessible toolkit to broaden both the conversation and access to knowledge for protecting America’s parks from climate change.

Often when we talk about climate change, the discussion can become overly academic and intimidating for someone who is seeking answers and strategies. Our goal was to make this knowledge accessible to as many people as possible.

“Creating an accessible tool was fundamental for us,” says Cawrse. “Often when we talk about climate change, the discussion can become overly academic and intimidating for someone who is seeking answers and strategies. Our goal was to make this knowledge accessible to as many people as possible. Park agencies have the choice of using the tool to engage with these strategies at a high level, but also to explore the issues and measures in greater detail, and take a deep dive into the many layers of information associated with them.”

As well as developing a tool that would be insightful to both experts and the public, the team also faced the challenge of designing strategies that could be specific enough to effect meaningful change at a given park, but universal enough to be applied without extensive local adaption. “The strategies needed to appeal to everything from downtown pocket parks to major park systems stretching thousands of acres,” explains Cawrse. “The tool needed to be transferable across locations and scales.”

Part of the team’s solution was to take their strategies into the real world by working with three different parks in Salt Lake City, Denver, and Evanston, Wyoming. By working with these three parks, varying widely in location and context, the team generated over 50 strategies deriving from their understanding of each specific park. “Once we developed this range of strategies from each location, we could cross-check them with other parks to make sure they were more broadly applicable,” explains Cawrse. “This not only confirmed that these strategies were realistic but also allowed us to develop additional strategies which were both flexible and effective.”

The future is about coming together, whether in a thousand-acre mountain park or a small backyard, and recognizing that everybody can help our environment adapt and mitigate against climate change.

As with all the tools explored in this article, climate.park.change will continue to evolve in response to new data and ideas. “We want this to be a living document,” says Cawrse, explaining how the team will continue to add new strategies that emerge from various park agencies, as well as expanding the tool’s coverage to other states beyond its Intermountain West base. The team also sees an opportunity for climate.park.change to host links and resources for other tools and datasets. “We have already had people reach out to us about other resources,” Cawrse explains. “Often these disparate resources are not linked by any central source. Our vision is for users to visit our tool, and use these links to continue their deep dive into other climate change strategies.”

In addition to this vision of a connected network of strategies, the team is also determined to continue with an ethos of accessibility. “Our hope is that the toolkit can be so accessible that an ordinary park user could come here and realize there are small steps they can take, even in their back yard, that can make an impact,” says Cawrse. “The future is about coming together, whether in a thousand-acre mountain park or a small backyard, and recognizing that everybody can help our environment adapt and mitigate against climate change.”

An architectural education can be hugely helpful in a career for software and interactive tools.

Climate.park.change is one of a growing list of engaging software and applications to emerge from Sasaki Strategies; a dedicated group within Sasaki comprised of designers, planners, data scientists, and software developers. The group’s output can vary widely, from interactive apps like climate.park.change to community engagement, data visualization, and storytelling. “Our team grew out of our planning practice,” explains Ken Goulding, who leads the Sasaki Strategies team. “We didn’t originally set out to design software, but over time we continually noticed opportunities to use software in creative ways, be it for animation, storytelling, or automation. This creative platform then steadily evolved into developing actual tools. In that sense, we grew organically from the needs of the practice.”

While operating as a defined team within Sasaki, the Strategies group maintains a strong link with the firm’s architecture, planning, and landscape teams, harnessing data and interactive tools that help their colleagues, as well as clients, understand and develop a design. “A clear majority of the time, our work is in response to the needs of a project team,” says Goulding. “Our other disciplines will notice a gap in the development of a project that we can help fill using digital tools. Other times, however, our work can involve standing back and surveying the wider industry, adopting a ‘research and development role’ of identifying opportunities that our teams or clients aren’t directly asking for.”

“One of the great benefits to having a dedicated in-house team like Sasaki Strategies is accessibility,” says Goulding’s colleague Chris Hardy. “Project managers and designers can meet us without delay, and develop solutions without the process itself becoming a project barrier. Without this in-house team, even having initial conversations with outside developers can be expensive, and coupled with the time delay, can form a barrier to creating something interesting. But we’ve lowered the threshold to a point where we not only produce great work but have perhaps also procured certain projects specifically because of this in-house team.”

The projects emanating from Sasaki Strategies are closely aligned with some of the most pressing issues facing both architecture and cities. Earlier this year, for example, the team developed a tool to help office managers quantify how much office space they would need for their staff following the COVID-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, projects such as climate.park.change, and Hardy’s upcoming tool for measuring embodied carbon in landscape architecture, demonstrate the need for using digital tools to understand the role of urban planning in either contributing to or mitigating against climate change.

This collaboration can go from ten linear miles of parklands to a quarter-acre site.

Anna Cawrse, who led the climate.park.change tool, cites a specific example of Sasaki Strategies integrating with the practice’s other disciplines; a collaboration with Sasaki’s civil engineering and landscape team on dredging works to a six-lake landscape in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The lakes and parklands currently serve as an important recreational asset for the local community, some of whom voiced nervousness over the project’s redistribution of 600,000 cubic yards of soil for redistribution along the lake edge to create parklands and aid restoration. With some residents worried about the impact of the works on their views of the lake, Sasaki’s team developed a digital model of the landscape, including every single building surrounding the lake, to aid design development.

“Using the model, we can evaluate and communicate in detail the impact of the new soil on surrounding views,” says Cawrse. “Even though no work has been done to the site, the model is allowing us to communicate the challenges and ideas in a way that nobody thought we could do, as opposed to just offering the residents anecdotal assurances. With digital tools, we can definitively prove it, which has been a major benefit to both us, our client, and the residents.” Like Goulding and Hardy, Cawrse sees strength in the Sasaki Strategies team’s ability to reach across disciplines and scales. “In Baton Rouge, we worked with the team on this major engineering, environmental, and recreational project,” Cawrse says. “But we’ve also worked with them on a small quarter-acre plaza, looking at human comfort and the experience of viewing the plaza from various angles. This collaboration can go from ten linear miles of parklands to a quarter-acre site.”

I’ve seen many people in our team start in an architecture background, and successfully transition into understanding and working with software.

Perhaps one of the most intriguing elements of Sasaki Strategies is the active involvement of people from architectural backgrounds, now engaged in developing digital tools. While the tactile, physical grounding of buildings appears divorced from the virtual world of coding, scripts, and data, the team observes inherent links between the two. “In some ways, it’s the same process,” says Goulding, who also comes from an architectural background. “You’re using empathy, an understanding of user experience, and an ability to understand schematics; steadily allowing the project to evolve in detail. Even concepts of modularity and scalability are directly linked to both realms.”

“An architectural education can be hugely helpful in a career for software and interactive tools,” Goulding adds. “I’ve seen many people in our team start in an architecture background, and successfully transition into understanding and working with software. Often, software has a reputation for being detail-orientated. When you come from a design background, it can instead be easier to think conceptually. But even if you do not fully understand the details, it’s often amazing what you are able to do.”

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.