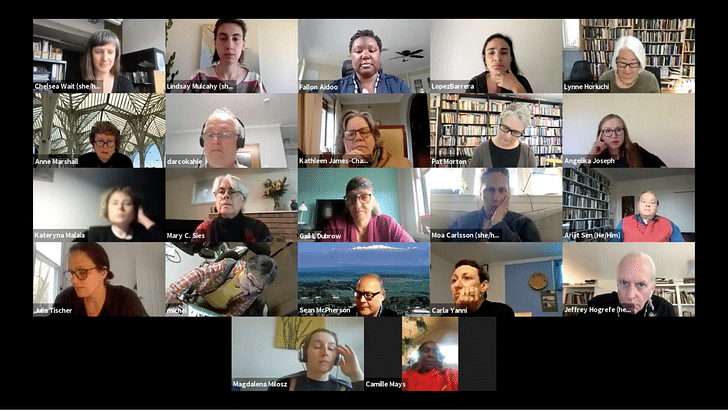

On Wednesday, May 5, I attended The Community Engagement and Social Justice in Architectural History Roundtable hosted by the Society of Architectural Historians (SAH) on Zoom. The event allowed me to reflect on the importance of interpersonal dynamics for architectural historians and practitioners who wish to do politically engaged work.

The roundtable was a ninety-minute workshop in which scholars of architecture and planning reviewed six research projects "united by a shared commitment to advancing equity and social justice." Part of the SAH Virtual 2021 Conference, the workshop included diverse topics from the theoretical implications of the 1969 occupation of Alcatraz, presented by Angelika Joseph, reviewed by Professor Arijit Sen to Valentina Dávila’s analysis of Venezuelan urban domesticity, reviewed by Professor Fallon Aidoo.

Likely the most memorable moment was an exchange between Chelsea Wait, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, and Camille Mays a community organizer and founder of the Milwaukee Peace Garden Project, affiliated with the Milwaukee-based Buildings Landscapes Field School. Wait, who is a white woman invited Mays, who is a Black woman, to present their collaboration, which forms a central part of Wait’s dissertation. Perhaps there is a leveling of class-based and race-based distinctions when we’re all in Zoom space, but the exchange cast into sharp relief the insular nature of the spaces in which architectural discourse happens.

Perhaps there is a leveling of class-based and race-based distinctions when we’re all in Zoom space, but the exchange cast into sharp relief the insular nature of the spaces in which architectural discourse happens. While architects love to use the word "community," the spaces in which we are trained are detached from everyday people.

While architects love to use the word "community," the spaces in which we are trained are detached from everyday people. Furthermore, while we are taught to throw around this jargon in front of our design critics, I can also remember my graduate school classmates casually referring to people as "architects" and "non-architects." The assumption is that we only talk to our own and that there is a stark divide between us and everyone else. At the SAH roundtable, the fact that I perceived Mays as being the one invited into the space of the SAH workshop—despite her tireless work in the community being studied in Wait's dissertation—goes to show that in architecture and academia, the unspoken boundary lines of race and class are quite firm, even in a workshop specifically designed to address equity and social justice. Perhaps this is my own prejudice speaking or fact that Mays was the only person—a single person representing a Black, working-class community—who was not a professor or doctoral student, but the event was memorable because someone from outside of the academy was sitting at the table.

As designers, we are trained to make the drawings for community mapping projects, for example, which are often the cornerstone deliverable of socially engaged work. Nevertheless, facilitator Professor Gail Dubrow acknowledged in her introduction that few, if any, architects, designers, planners, and historians have any formal training that prepares them to do work directly with the actual members of underserved communities (or really with communities at all, I might add).

Architects, planners, and historians of the design disciplines often write about the relationship between the built environment and society, but what experience does our education give us to engage with real people?

Indeed, Dubrow said, the event reflected "the struggles to come to grips with the inadequacy of established modes of research and norms of professional practice when it comes to working with communities whose past present and future figure centrally in our projects." Architects, planners, and historians of the design disciplines often write about the relationship between the built environment and society, but what experience does our education give us to engage with real people? Much less, what does a discipline and academy led by white men who historically have catered to the interests of other wealthy, white men model for students and future practitioners who wish to intentionally and thoughtfully address the interests of working-class people? How do our educational institutions foster the effort towards greater equity and inclusion of the Black, Indigenous, and people of color that have so often been marginalized by the state, corporate, and financial interests that architecture supports?

I’ll be continuing my reeducation with the Architecture Beyond Capitalism School (ABC School) being hosted by The Architecture Lobby, where I hope to discuss and build with other architects who want to imagine alternative modes of practice and collectivity. Related to the role of the archive in architectural scholarship, I also plan to attend the Unearthing Traces Doctoral Workshops hosted by the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), which promises conversations about "about memory processes, power structures in archival practices in relation to the built environment and material architectural traces."

The question is, who will be at the table (or in the Zoom room)? In the closing comments at the SAH workshop, participants discussed the fact that the society members presenting projects for this session were overwhelmingly female. To explain this, Dubrow reflected on her architectural education: "Relational skills were not really emphasized." Community-engaged architectural research is not only part of an "ethnographic" turn but also rooted in "feminist praxis," which is attentive, among other things, to human needs and emotions. To interrogate architecture’s relationship to society, we must first learn to talk and relate to people in an empathetic way, something I did not see modeled in any of my final reviews in architecture school. Perhaps the most important thing these summer schools will offer is spaces outside of traditional institutions to practice alternative ways of communicating and relating to each other.

To interrogate architecture’s relationship to society, we must first learn to talk and relate to people in an empathetic way

The Community Engagement and Social Justice in Architectural History workshop have recorded a video and chat transcript available to the general public. It was facilitated by Professor Arijit Sen, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee; Professor Gail Dubrow, University of Minnesota; and Professor Sean McPherson, Bridgewater State University as part of the Asian American and Diasporic Affiliate Group of the SAH.

Dante is a PhD student studying the History and Theory of Architecture at Princeton University. He is a licensed architect in New York State.

1 Comment

"While architects love to use the word "community," the spaces in which we are trained are detached from everyday people."

Listening to 'everyday people' need not exclude the kind of high minded research that historians and theoreticians thrive upon, it's simply a reality check that the subject at hand is entirely lived in by everyday people. I hope you can make inroads into this important issue for all fields of architecture.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.