Not too long ago, a novel graphic representation, rebelling against the digital tools and techniques that dominated the past two decades, took the architecture world by surprise. Post-Digital Drawing, coming mostly from European offices, started propagating across professional circles, competitions, and academia. This style of representation, noted by Sam Jacob, embraces digital technology in a critical way; utilizes digital tools like Photoshop and Illustrator, and techniques like drawing and collage without aiming for realism. Instead, "this new cult of the drawing explores and exploits its artificiality, making us as viewers aware that we are looking at space as a fictional form of representation. This is in strict opposition to the digital rendering’s desire to make the fiction seem 'real.'" However, by taking a look at the work of emerging practices, competitions, and academia today, one can discern that an evolution starts to emerge. Ironically, this evolution of the Post-Digital aesthetic seems to be going in the opposite direction to its original trajectory, embracing the digital render.

"Architecture Enters the Age of Post-Digital Drawing" was published in Metropolis Magazine in March of 2017. It highlighted the work of Office KGDVS, Fala Atelier, Point Supreme, and others who started developing a line of work that, probably for the first time, criticized digital technology from the representational perspective. They rejected the capabilities of photorealistic renders in favor of tools like Photoshop and Illustrator to establish a dialogue with pre-digital techniques of representation, namely, drawing and collage. Through this rejection of the 'glossy hyper-realism,' new graphic qualities, that paint a fictional picture of architecture, began to emerge. This widened the gap between architectural representation and the image of the finished product, in which the unpredictable lies, previously shortened by the powerful capacities of photorealistic renders. The style took over a huge portion of the architecture community, from a multitude of emerging offices, in Europe and other parts of the world, to competitions and academia.1 Sam Jacob's influence also helped its propagation. His pedagogy at the Architectural Association, Yale, and the University of Illinois at Chicago became a reference for other institutions. While this constitutes the formal side of its development, Instagram and other social media platforms also leveraged its proliferation through 'popular (architectural) culture.'2

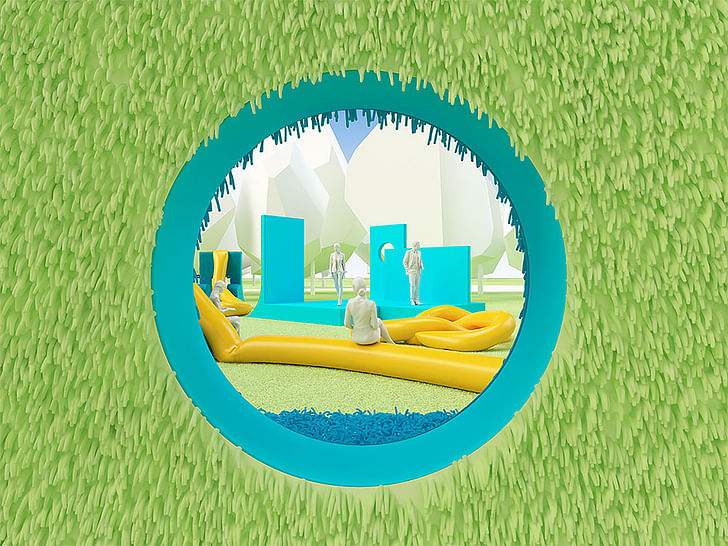

At first, the proposition of Post-Digital Rendering can seem self-contradictory. This notion, according to Jacob, is at its core opposite to photorealistic renders. However, in the work that I am referring to, it is possible to see the utilization of rendering software and sophisticated techniques to pursue the same fiction that their predecessors were after. Realistic lighting, pristine texturing, and high-resolution 3D models are no longer being used exclusively to depict a real future but rather to create fictional scenarios that inflict some kind of criticism on architecture. Similar to the return of drawing that Jacob envisioned, this type of work is making an attempt at elevating the render, not as renders of architecture but as "architecture itself." In this new work, it is possible to trace a line from Post-Digital drawings to renders; flatness, raw textures, and found cut-out figures from the internet got translated into dreamy ambient lighting, exaggerated textures, and displacement maps as well as found 3D models from online archives like CGTrader and Turbosquid, evoking a similar kind of indifference.

They rejected the capabilities of photorealistic renders in favor of tools like Photoshop and Illustrator to establish a dialogue with pre-digital techniques of representation, namely, drawing and collage.

Perhaps, Jacob saw this style as a beacon of hope for drawing, putting it at the forefront of his thesis. However, if one follows the hard distinctions between photograph, drawing, and image set by John May, the thin line that divides Post-Digital drawings from renders begins to blur. In "Everything is Already an Image," May encompasses all digitally created visual material in the image category; for they are fundamentally different from the kinetics of drawing and the chemical procedures of photography. "Unlike photographs, in which scenic light is made visible during chemical exposure, all imaging today is a process of detecting energy emitted by an environment and chopping it into discrete, measurable electrical charges called signals, which are stored, calculated, managed, and manipulated through various statistical methods." These distinctions help open up the Post-Digital discourse to encompass all kinds of images, disregarding whether they are created through lines, cutouts, or three-dimensional models, lights, and textures. This shifts the focus towards the qualities that emerge from them instead of their means of creation.

Having established that the term 'image' is best suited for Post-Digital work in our contemporary context, due to its digital nature, it is now possible to highlight what some of the key components of this aesthetic category are and what has caused its migration to a different medium. A core distinction between the Post-Digital drawings and renders is that the former are produced mostly by European practices, like those mentioned in Jacob's article. In contrast, the latter are the outcome mostly of offices from the US, like office ca, T+E+A+M, Future Firm among others. What is common for both, is that they have been, for the most part, produced by young architects, who perhaps don't have large commissions lined up but rather have a significant involvement in the academic environment. Similar to the original 'drawing cult,' the propagation of this second wave has concretized thanks to competitions and student work repositories, such as the HOME Competition, Arch Out Loud, or The Archaeologist, replacing the once Post-Digital drawing archive par excellence, KoozArch.

With an image in our head of how a Post-Digital rendering might look, it is important to pay respect to Sam Jacob's efforts of thorough description of the Post-Digital aesthetic. Without getting into too much detail, I would argue that the dissimilar opportunities for young architects in the construction industry in Europe vs. those in the US are in great part responsible for this shift in medium. While young firms in Europe enjoy a plethora of competitions and build up their names by building, in the US, many young firms have to rely on academia and exhibitions to put their ideas out, giving them the freedom to experiment with alternative materials or unorthodox assemblages. These are some of the qualities that start to come through in these Post-Digital images.

office ca, for instance, heavily relies on soft materials and forms, aspects that are extremely complicated to accurately represent through mere drawing and collage. Instead, the rendering software has allowed them to incorporate physics simulations into their work without compromising accurate representation. T+E+A+M's interest in material assemblages and the utilization of found objects puts them in a position where generic texture overlays in Photoshop are simply not enough. Instead, the render allows them to synthesize the specific materials that they are working with as well as the legible spatiality that collage lacks. In the work of Future Firm, their speculative projects manifest sometimes not as material, but rather as social or performative interventions that inherently require a rejection of the typical architectural visualization techniques that are used in their more conventional projects. They mitigate this by giving greater precision to the 3D models and rendering of the objects responsible for setting the mood of the image, shifting the attention in their work from the architecture to the activities that emanate from them.

Realistic lighting, pristine texturing, and high-resolution 3D models are no longer being used exclusively to depict a real future but rather to create fictional scenarios that inflict some kind of criticism on architecture.

Like in other instances, the most extreme examples can be found in the experimental realm of competitions. And to me, this is where the movement has been notably building up strength. The HOME Competition, which started in 2018, has increasingly become a repository of this type of expression, showing that the movement has indeed gained momentum in the past few years. In there, it is possible to observe a variety of examples in which renders have become a tool for criticism in architecture. The fantastic environments that have emerged are only possible through this tool, as the powerful software has the potential to create conditions of reality but also the flexibility to push them beyond it. The accurate lighting, the pristine texturing, and the high resolution of the 3D models that create a scene give us a feeling of satisfaction through familiarity, because it resembles reality. But once those are manipulated through high saturation, exaggerated mapping, and coats of reflectivity, translucency, and other parameters of artificial materials, they are "making us as viewers aware that we are looking at space as a fictional form of representation."

It is important to note that although

Sam Jacob's observations suffered from nearsightedness by being

confined to a specific mode of representation, they laid the ground

for its evolution. A crucial aspect introduced by the Post-Digital

was the criticality that digital media has the potential to perform,

not only at a formal or structural level but also at the

representational one. It is clear that the work that is being

produced with their assistance has the potential for much more

complex representational techniques than its European homologs.

Yet, it is also crucial to trace a line between these two vectors, as

their attempts to create fiction through architecture indicate a

stage of criticality.

1 https://www.archdaily.com/888739/these-6-firms-are-spearheading-the-post-digital-drawing-craze-in-mexico.

2 Tursack, Hans. "The

Problem With Shape." Log,

no. 41 (2017): 45-53. Accessed March 25, 2021.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/26323715.

I am an architectural designer originally from Mexico, with studies in the Illinois Institute of Technology, the Texas Southmost College and the Swedish Royal Institute of Technology.Throughout my education I developed an interest in the intersection between history and technology in architecture ...

29 Comments

"Every architect should practice drawing, but increasingly, few do."

Richard Meier

"Hold my robe"

whatever works to get your message across

"post digital renderings" which are in fact, entirely digital. Come on. Really? Twist language all you want, it's digital.

The entire article is couched in so much academic language cribbed from humanities departments that it is hard to tell what the thesis even is.

"Realistic lighting, pristine texturing, and high-resolution 3D models are no longer being used exclusively to depict a real future but rather to create fictional scenarios that inflict some kind of criticism on architecture." Criticisms that absolutely nobody outside of a tightly curated and controlled field of chosen academics gives a single fuck about.

Changing the words does not change the end-product and this is just another form of digital manipulation. In the end tho, there is very little quality of design in these examples. Still can't beat the fat charcoal stick on textured paper or sharpie on canary-yellow trace.

I'm in love. I've hated rendering techniques - representative realism - forever. These images are provocative, sexy, and don't pander to client "expectations". The author is on point. I've been waiting for these. See Perry Kulper and others. I love when people get tied in knots over semantics.

I'd agree that photo realism renderings get far too much attention... even if it is what sells most projects to clients and investors. However, mashing up mirrored textures and layering PS filters is no substitute for quality drawings. The Kulper drawings are really nice and suggest thoughtful use of imagery vs pressing the render button or twisting language.

I just think that architecture has finally figured out how to connect the digital, with the idea. It's no longer an afterthought, representation and idea have been woven. That, for me, is Post-Digital.

I think most would agree with the concept of the article re: renderings, but the semantics gets in the way unfortunately. "Post-" indicates something after. If post-digital is simply more digital and not really changing the digital tools or the digital touch, it's not really post-digital. If the article was using the term "post-photorealistic" or something similar, I don't think there would be as much complaint. Words matter and unfortunately the creator(s) and users of this term haven't really chosen their words carefully enough. I could make a better argument that drawing with a stylus is more post-digital than what is being discussed here.

Even looking back at the jumping off point of the Metropolis article, the term isn't even defined. The author, Sam Jacob, simply drops it in the penultimate paragraph and assumes we all understand the meaning. Unfortunately, this is all to common in architectural literature and is probably one of the defining characteristics of archi-speak ... make up words and go along with it like the emperor's new clothes.

I'm not going to say you're wrong, I'm going to say that you aren't going deep enough.

Postdigital

"Giorgio Agamben (2002) describes paradigms as things that we think with, rather than things we think about. Like the computer age, the postdigital is also a paradigm, but as with post-humanism for example, an understanding of postdigital does not aim to describe a life after digital, but rather, attempts to describe the present-day opportunity to explore the consequences of the digital and of the computer age. While the computer age has enhanced human capacity with inviting and uncanny prosthetics, the postdigital may provide a paradigm with which it is possible to examine and understand this enhancement."

I will say that Architecture, and the practitioners, purveyors, writers, and academics, have always riffed, and been wrong, but they never failed to push the envelope. For that, I am grateful. Plus, you know what, this person deserves praise, and constructive criticism, not whatever this is. He's at least trying.

Or, maybe, just maybe, I'm being a jerk, for thinking he's got something to say, and this post-digitalness is a real thing.

Perhaps you're right b3ta. I didn't try to do a deep dive, but should I have to in order to understand a feature article on the site? We all share a specialized language that non-architects and designers may not understand ... but we should at least be able to understand each other, right? If your writing requires a special understanding of terms the audience may not be up to speed on, it's generally on you, the author, to explain it sufficiently to bring the audience along. Perhaps that's just my baggage though. I wanted something easy to digest and kept getting lost along the way.

Should you? I don't know. What I do know is that when PoMo, and Decon hit, many went deeper, reflected on what Kipnis and others were spitting. And that was prior to the internet. I didn't need to go far, and I found simple, digestible source material on two Wikipedia entries.

Producing images for the Instagram age

I’ve been abstracting my renderings for years for a very practical reason- avoid the client saying “why does this stone look different from the one in the drawings!” I make it so abstract that it’s obviously not to be taken literally. A rendering is about conveying a feeling or concept of a space, not what it’s going to look exactly like.

I've been advocating for this in our office for years... still, ownership is swayed by the shiny render button the junior and fresh grads all know how to press.

Sometimes I print out a sketch up model, lay over some trace, sketch over it with markets, pens, paint, whatever, and then scan it and play around with photoshop...

Post-digital should be called Super-digital, just to not get stuck in irrelevant semantic discussions...

Yes!

Not post-digital, but digital non-realism, maybe?

Been advocating this for years, but seems like the super shiny chinese renders are what clients want, especially the low grade clients with a shit ton of money (which is all of our cilents)

Well they gotta pass on the same renders to homebuyers, investors, and other moneymen who want to know exactly what they're paying for. Not to mention government agencies. For these, verisimilitude is essential. A bank would probably not accept a pretty collage as a representation of what a multi-million dollar project is supposed to look like. Same for homebuyers who want to know where their money is going.

Says who?

Developers and real estate agents, especially those catering to foreign buyers

Again, that's you. I'm suggesting that these images may, or may not be for group you cite. Not all products are for all audiences.

Of course. The vast majority of projects don’t involve some brookfield bloke approving images or a homebuyer from Shanghai putting in a deposit.

Is this post-digital?

I posted a YouTube video and disappeared. Hope it stays this time

No videos possible in features or news iirc

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.