Learning how a design studio begins its journey into professional practice is an eye-opening experience. For Matter Design, they started with a mission to build projects they designed themselves. While this response may seem simple in its approach, they explain, "we were much more interested in the means, the methods, and communication between design and materials." Yet, four years after our Studio Snapshot interview with co-founders Brandon Clifford and Wes McGee, the practice has grown into a catalyst for bridging architecture, speculative design, and interdisciplinary social missions.

Archinect re-connected with Clifford to discuss recessions, running a speculative design studio, and how the firm's latest project AquíAquí is more than just a public space project. Clifford shared, "I can say that we have built Matter Design on a series of speculative built works that serve as individual challenges to default practice." In response to the development of AquíAquí, he explains, "we tried as much as possible to develop a design language that could radiate space around and through without bounding it at the perimeter. The hope here is to not only respond to issues of COVID but to ensure that unforeseen futures could provide space for the community without being confined to a singular notion of space."

Since 2017, a lot has changed since we first spoke with the duo. Their practice survived not one but two recessions, expanded their team with the joining of Johanna Lobdell, and have established themselves as key players in research and speculative design approaches. However, the strength of their practice doesn't lie in their awards but their growth and design truths as they continue to develop work that "is both playful and rigorous, leveraging alternative ways of thinking to reconsider the future."

Our work tends to goal towards disrupting default solutions instead of contributing to incremental advancements of established knowledge.

Every practice has an origin story, and for Clifford and McGee, it began while studying at Georgia Institute of Technology. He studied Architecture and McGee was studying Industrial Design. However, it was in the shared woodshop that the duo met. "This was in 2005 when digital fabrication was picking up in architecture schools, and we defiantly shared a passion for the contradictory interest of being hands-on but operating within the digital context," explained Clifford. "We founded Matter Design with the simple principle that we would build the projects we design ourselves. As simple as it sounds, it was honestly a rebellion against the flood of young practices that were largely based on renderings and advanced visualizations at the time."

Many promising young firms seek to start a practice that reflects their hopes and aspirations that they may not accomplish when working for a more established firm. "We were much more interested in the means, the methods, and communication between design and materials. BUT, while Wes and I are the official founders of Matter Design, Jo has been there all along," he explains. "Matter Design has a very fuzzy start date and a pretty loose structure which offers us the freedom to invite collaborators in, to find experimental topics, shift and restructure as needed. This is all to say that Matter Design is a living entity and, depending on who you ask, has a number of origin stories. We see this as a strength."

When reviewing their projects it's easy to imagine their built works turning heads. Yet, aligning with the practice's core beliefs, Clifford shared that their design ethos focuses on "big picture issues that necessitate alternative approaches. We discover those approaches by researching and mining abandoned knowledge from our ancient past. The goal of this approach is not to return to some romantic idea of the past but to shed the contemporary thought that blinds us to viable paths forward. Our work tends to goal towards disrupting default solutions instead of contributing to incremental advancements of established knowledge."

I was keen to learn more about their favorite projects and how they approached design challenges through research; I asked Clifford to dive into MatterDesign's past. Doing so helped me reveal their ability to navigate and continue to work during the tumultuous year that was 2020.

Do you have a favorite project?

The McKnelly Megalith has a very special place in my heart. It is the result of an experimental architecture studio that I co-taught with Mark Jarzombek at MIT. The studio came together around an unexpected crisis that occurred mid-semester. As a collective, shifted from individual explorations towards a central goal of considering community, event, performance, and theatricality to memorialize the memory of the McKnellys with a creative megalithic performance. Not only was that experience incredibly meaningful for me, it dramatically changed my approach to teaching and redirected my research into new territory. I thought I would entertain this strange megalithic research once and move on, but now it is essentially all I do! It is also the moment the work pivoted from facing fabrication to facing society.

Describing 2020 as a “challenging year” may be an understatement. But with a practice like Matter Design, whose expertise lies in research, speculation, and design application were there any big challenges or takeaways? How did you all adjust?

2020 snapped me right back to 2009. In the wake of that financial crisis, I witnessed each of my friends, classmates, and co-workers losing their jobs in architecture at a pace that became numbing. I too saw the writing on the wall and I prepared my application to return to school for a master’s degree. The trauma of that era instilled in me an entirely new motivation… not to return to school to become a practicing architect, but to be nimble--to not be reliant on clients, the financial system, nor a narrowly defined discipline. This is not to say anything about practice other than to situate my own trauma relative to that crisis. I think this also greatly explains the efforts we make at Matter Design to shed the disciplinary coat with which we are attached to. I’m actually the only architect. Wes is an engineer and designer (though fully entrenched in architecture) and Jo is a sculptor and graphic designer. We also collaborate with composers, writers, material scientists, historians, chefs, etc. I bring this all to the surface because 2007-9 shaped Matter Design into what it is, and 2020 tested that form. While 2020 has brought a number of challenges, it also highlighted so many issues that necessitate attention.

2020 snapped me right back to 2009. In the wake of that financial crisis, I witnessed each of my friends, classmates, and co-workers losing their jobs in architecture at a pace that became numbing.

The trauma of that era instilled in me an entirely new motivation… not to return to school to become a practicing architect, but to be nimble--to not be reliant on clients, the financial system, nor a narrowly defined discipline.

2007-2009 shaped Matter Design into what it is, and 2020 tested that form. While 2020 has brought a number of challenges, it also highlighted so many issues that necessitate attention.

Learning but most importantly improving design decisions from a social, political, and institutional level take precedence now more than ever. How have your design perspectives and process changed?

This is a really interesting question because I think it skips over the individual project and asks about the broader implications, mission, or method with which a design research lab operates. Some call that the (upper case) Project vs project. But yes, this meta-level is exactly what I am finding myself prioritizing at this moment. I would be interested to know whether this is the point in my career when that shift occurs, or if it is something unique about the time we are in, but for myself, I can say that we have built Matter Design on a series of speculative built works that serve as individual challenges to default practice. Individual notes that could build to an impactful and timeless symphony, or to a one-hit-wonder pop song, depending on how it is composed. At the moment, I am shifting my attention to consider that composition more. Not to tell the overall story, but to incorporate proper feedback loops that are required for sustaining research that ensures feedback, instead of moments of declaration that fizzle. I wouldn’t argue that we have figured it out, but certainly, the perspective has changed as to how to construct research agendas that progress in meaningful ways.

Adapting to a post-covid world is an ongoing reality for many. After learning about their latest project AquíAquí, I asked Clifford to discuss the roles architecture and activism played in relation to public space. "AquíAquí is an incredibly challenging and exciting project for us," he started. "First of all, it was entirely conceived by a collaborative group, including the design activists at PDA Collective, non-profit group USMC Strategic Alliance that provides social programming for the community, as well as CEMEX Global R&D who are invested in exploring construction approaches that can contribute to society. AND, these collaborators are all working in the complex territories surrounding the migrant crisis, border politics, as well as COVID."

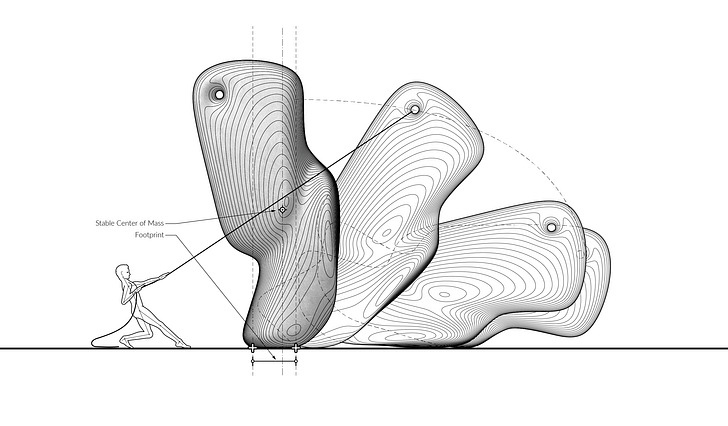

AquíAquí defines a range of spatial typologies without constraining space.

The project's design intention centered around one question, "how can we build community by bringing people together?" While several firms are attempting to tackle future design approaches with COVID-19 and social distancing in mind, Clifford continues to explain how a project like AquíAquí acts as an example of what's possible. "The challenges of COVID and social distancing are, if nothing else, a clear call for alternative approaches to architecture. When positioned adjacent to the central question, challenges such as social distancing actually build productive friction in the research and they bring into focus the failures of default practices. As a central premise, AquíAquí defines a range of spatial typologies without constraining space. We tried as much as possible to develop a design language that could radiate space around and through without bounding it at the perimeter. The hope here is to not only respond to issues of COVID, but to ensure that unforeseen futures could provide space for the community without being confined to a singular notion of space—one that has been dominated by a utilitarian notion of enclosure, which in turn, severely limits architecture’s capacity to adapt through time."

How can we build community by bringing people together? The challenges of COVID and social distancing are, if nothing else, a clear call for alternative approaches to architecture.

When positioned adjacent to the central question, challenges such as social distancing actually build productive friction in the research and they bring into focus the failures of default practices.

What drew me to learn more about this project wasn't only its public space agenda but its location. The project is located in the US and the Mexican border region. Due to the ongoing mismanagement and the lack of proper leadership regarding the US and Mexican border, especially during the Trump administration, AquíAquí offers new strategies for social programming and problem-solving within architecture and collaboration with social organizations. I asked Clifford to expand on this and a closing question regarding public space for the United States.

El Chamizal is truly an epicenter of condition that spans the continent and we are lucky enough to have partnered with Cecilia Levine of El Punto who has been working on generating social programming to bring a community together that has been divided by a border on that central site.

"El Chamizal is a charged site," he shares. "It has been a kind of in-between territory for two nationalities as the Rio Grande meandered, creating a shared plot of confusion. Not only is this site a relatively (within the past century) recent political quandary, but has also served as a regular gathering destination for the Native American communities in the region. The frictions over territory, drug-trafficking of the past decade, the migrant crisis of our current moment, as well as common trade and identity have imposed a strange collision point on this central site that itself serves as a vacuum for all. El Chamizal is truly an epicenter of condition that spans the continent and we are lucky enough to have partnered with Cecilia Levine of El Punto who has been working on generating social programming to bring a community together that has been divided by a border on that central site. This mission is what fuels the rest of the collaborators to consider what we can do to catalyze and spatialize these gatherings. This deeper history also challenged us to reconsider architecture as something nimble, providing agency back to the community in order to future-proof the work itself. We’ve never thought of AquíAquí as architecture itself. The concrete elements are always seen as a scaffold for the community that surrounds it."

What are cities getting wrong about designing for public spaces and people? How can a project like AquíAquí shape a new approach?

In no way am I claiming that AquíAquí is a solution to this massive problem, but it is the beginning of inquiry into how else might we think about architecture? How can architecture bring people together to provide warmth and entertainment?

I wouldn’t say that cities are getting any one thing wrong when thinking about people and public space, but I will say that it baffles me that we collectively default to shelter as the exclusive provision of architecture when confronted with a challenge. Whether it be natural disaster relief, or a migrant crisis, or refugee settlements… society has packaged architecture into an extremely narrowly defined category of resisting the elements—tent cities. In no way am I claiming that AquíAquí is a solution to this massive problem, but it is the beginning of inquiry into how else might we think about architecture? How can architecture bring people together to provide warmth and entertainment? Instead of focusing on exclusion, we tried to re-envision what the hearth offered society before we abandoned it for central heating. I feel strongly that if we can better understand the value of that timeless act, we might be able to better situate architecture as a provider instead of shelter for these temporal events that shake society.

Instead of focusing on exclusion, we tried to re-envision what the hearth offered society before we abandoned it for central heating. I feel strongly that if we can better understand the value of that timeless act, we might be able to better situate architecture as a provider instead of shelter for these temporal events that shake society.

Concluding the interview Clifford connects his role as an academic to his practice. As an Associate Professor and M.Arch Program Director at MIT, he has the ability to step in and out of theory and practice. I asked him how he hopes to transform the current discourse between architectural research and speculative work?

"I run a research lab that is often confused for a professional architecture office," he shares. "That, we are not. BUT the confusion is important to us because we are able to operate as that bridge. I say this because we do not accept clients. That sounds pompous, but we honestly don’t know how to handle them, nor are we interested in reshaping our research trajectories to fit the market. Instead, we construct architecture works that appear to be commissions, though in reality, they are partnerships with organizations that would like to collaborate on a mission to impart change in the world. Whether that be in the field of education, the building industry, climate change, or community in the case of AquíAquí. Each of these projects can be understood through the lens of a practicing architecture practice, but are generated in an entirely different model—one that prioritizes mission before service. In this respect, Matter Design has always seen itself as a bridge… first between design and production, between academy and practice, and now between interdisciplinary social missions."

Matter Design has always seen itself as a bridge… first between design and production, between academy and practice, and now between interdisciplinary social missions.

For young practitioners and firms emerging out of 2020 do you have any tips or notes they should keep in mind during their early years?

I mentioned previously my own story with the previous financial crisis. I think it is worth saying that 2020 is not unique and should not be tossed aside as if this is only temporary. These kinds of events challenge us at a cadence of about 10 years. I don’t dare challenge young practitioners to do anything in particular, but I would raise this warning that stasis is unlikely to be our future – think nomadic (in a conceptual sense).

Katherine is an LA-based writer and editor. She was Archinect's former Editorial Manager and Advertising Manager from 2018 – January 2024. During her time at Archinect, she's conducted and written 100+ interviews and specialty features with architects, designers, academics, and industry ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.