In this latest installment of Fellow Fellows Archinect connects with Benjamin Vanmuysen, the 2019-2020 Harry der Boghosian Fellow at Syracuse University. Vanmuysen shared with Archinect the details of his work and his latest fellowship exhibition in October. He also discusses the rules and methods in which architecture is currently being taught and will be changing going forward. "The COVID-19 pandemic has really shaken up the academic world and brought traction behind some pressing social issues," shares Vanmuysen. "It’s crucial for institutions to teach students the social and political implications of our discipline."

Fellow Fellows is a series that focuses on the role fellowships play in architecture academia. These prestigious academic positions can bring forth a fantastic blend of practice, research, and pedagogical cross-pollination, often within a tight time frame. By definition, they also represent temporary, open-ended, and ultimately precarious employment for aspiring young designers and academics. Fellow Fellows aims to understand what these positions offer for both the fellows themselves and the discipline at large by presenting their work and experiences through an in-depth interview. Fellow Fellows is about bringing attention and inquiry to academia's otherwise maddening pace while also offering a broad view of the exceptional and breakthrough work done by people navigating the early parts of their careers.

What fellowship were you in and what brought you to that fellowship?

I was the 2019-2020 Harry der Boghosian Fellow at Syracuse University. Prior to joining the School of Architecture, I worked at the office of Diller Scofidio + Renfro in New York. While this experience was educational, I wanted to pursue a career in academia and further develop my own design interests. A fellowship is a great opportunity to explore your ideas and research through teaching, discourse, and eventually in the format of an exhibition. The Boghosian Fellowship was particularly attractive to me due to the extraordinary faculty that teach at the school of architecture.

What was the focus of the fellowship research?

My research explored the definitions of two opposite design extremes: underdesign and overdesign. Both conditions have negative connotations and are active terms within our architectural jargon, but have never been further investigated, nor defined.

To gain a deeper understanding of the extremes of the design spectrum, the fellowship research ignored the middle ground of ‘good’ design and devoted its attention to the design processes of under-and-overdesign. While the former is careless, if not decidedly lazy, resulting in dull and nonspecific architecture, the latter is overzealous and studied, resulting in architecture that is unnecessarily complex, overdone, and too often ostentatiously intellectual or ornamental.

Instead of categorizing existing design work into the concerning design extremes, the aim of the fellowship was to gain intelligence by doing. My students and I put ourselves in the shoes of the underdesigner and overdesigner during the spring 2020 semester. We counterintuitively shortened and extended our design process in order to achieve the desired diametrical design conditions. Through this extreme value analysis, we were able to evaluate the repercussions of time-variation on our design outcomes and measure its added or perhaps subtracted value.

What did you produce/ teach, and how has it reshaped your relationship to architecture and academia?

As the Boghosian Fellow, I taught a research seminar in the fall semester, which scrutinized multiple case studies in the pursuit of design extremes. Students didn’t only analyze their projects through readings, discussions, and presentations but also dissected them into the respective design extremes through drawings.

In the spring semester, this analysis turned into doing. Both my design seminar and Vertical Critic Studio revolved around design velocity. The students in my studio conceived a flagship store in the Hudson Valley, which was simultaneously under-and-overdesigned. By designing their stores in different gears, the students were able to, on one hand, prematurely cease their design progress and, on the other, to exhaust it. This process didn’t only allow them to gain a better understanding of the concerning design extremes but also helped them to situate their own middle ground for future design endeavors.

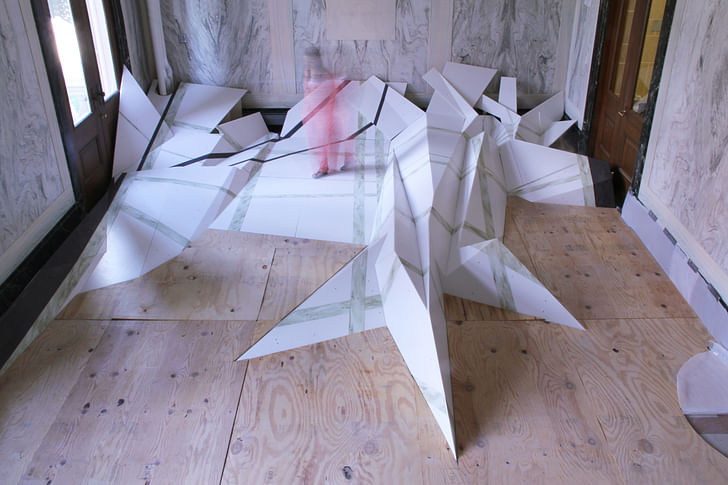

My spring seminar imposed the same speed limits on the design of the fellowship exhibition in the Marble Room at Slocum Hall. Multiple elements of the exhibition space – floor, wall, ceiling, door, and duct – were designed with varying degrees of labor, design investment, and consideration. The main feature of the exhibition was an overdesigned floor, which was manufactured out of faux marble in response to the authentic and veined marble walls in the existing exhibition space. Dupont Corian generously donated the necessary sheets to complete the installation. This new supplementary surface didn’t only react to its host environment materially, but also geometrically. The seemingly wrinkled surface only provided a selective area that was horizontal and pedestrian-friendly. In other words, the hyper specificity of the floor controlled the movement of its visitors.

In contrast with the overdesigned floor, the underdesigned surface was flat, flexible, and undetermined. Its scope comprised the residual space between the partition wall and the Corian floor. It was made out of an easily available and building-code compliant material: half-inch thick fire-rated plywood.

As the limits of the design spectrum remain subjective, the intention of the exhibition was for visitors to appraise for themselves the negative (and positive) implications of both under-and-overdesign. The juxtaposition of these two negatives aimed at inducing an ongoing conversation on the varying efforts devoted to design.

The fellowship has been a great opportunity to gain teaching experience and be able to work with students on a project [...] Perhaps most importantly, the fellowship gave me the time and resources to flesh out ideas and translate them into an installation, which will be my calling card for future opportunities.

How has the fellowship advanced or become a platform for your career?

The fellowship has been a great opportunity to gain teaching experience and be able to work with students on a project. I have become more acquainted with the process behind course preparation, which will undoubtedly help me with further teaching endeavors. Perhaps most importantly, the fellowship gave me the time and resources to flesh out ideas and translate them into an installation, which will be my calling card for future opportunities. I also cherish the conversations I’ve had with my colleagues at Syracuse University in regard to my fellowship or teaching in general, which have influenced my pedagogy.

What are you working on now, and how is it tied to the work done during the fellowship?

I’ve been teaching part-time at Syracuse University and finally opened my fellowship exhibition on October 9th, which was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The gallery opening was held virtually and included a discussion between myself and Dean Michael Speaks. My current work tries to distance itself from the fellowship but is at the same time closely related. The contrast between high and low design remains recognizable motifs throughout my work and will most likely keep influencing my future pursuits. I have also been experimenting with the Corian Solid Surface material, which we used to fabricate the overdesigned floor, and hope to be able to integrate it in future projects.

It’s a great introduction to academia and a way to expose your research to the faculty and student body of a particular architecture school.

With the pandemic impacting the future of architectural academia and exhibition, do you have any advice for future fellows applying?

If you’re interested in teaching and developing a research project, I can only recommend pursuing an architectural fellowship. It’s a great introduction to academia and a way to expose your research to the faculty and student body of a particular architecture school. In terms of the application process, I would recommend keeping your proposals open-ended as your initial ideas will most likely evolve and perhaps divert during the course of the fellowship, which makes it all even more exciting.

As designers, we have agency and can make a difference.

Where do you see the future of academia headed? What do you hope to see as schools begin to address today’s issues? Where are areas where institutions can improve?

The COVID-19 pandemic has really shaken up the academic world and brought traction behind some pressing social issues. It’s crucial for institutions to teach students the social and political implications of our discipline. At Syracuse University this fall, multiple studios dealt with the city’s issues of housing segregation, which ranks 9th in the nation. The inclusion of such matters in school curricula, I believe, is a step in the right direction, and I would love to see more of it. As designers, we have agency and can make a difference.

Katherine is an LA-based writer and editor. She was Archinect's former Editorial Manager and Advertising Manager from 2018 – January 2024. During her time at Archinect, she's conducted and written 100+ interviews and specialty features with architects, designers, academics, and industry ...

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

No Comments

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.