Why are introductory architecture courses often packed with dense, off-putting jargon? It’s a question I didn't anticipate asking an esteemed architectural historian and current Harvard GSD professor, yet after I unintentionally offended K. Michael Hays by publicly airing my annoyances with jargon and difficulty as part of a recap of a review of his new online course, I realized that I needed to ask it. In fact, I owed it to the Professor; it’s unfair to criticize someone’s teaching style if one hasn’t thoroughly experienced it, although I've taken courses taught by others that used a similar approach.

However, I also couldn’t fully retract my comments because I was still bothered by the underlying issue: why are these courses so purposefully difficult? In an era when architecture is attempting to become more diverse and attract a wider group of students from different backgrounds, it seems sensible to offer introductory courses that use readily comprehendable language. This discussion was prompted by Hays’ online architectural history course, The Architectural Imagination, which can be publicly accessed through the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. To set things right, I asked the professor and the producer of the course, Lisa Haber-Thomson, if they would be willing to be interviewed about his pedagogy, the choice to use jargon and difficulty, and the newly accessible format of the course itself, and they generously agreed.

To prepare for this interview, I signed up for the course and also carefully reviewed specific clips that Hays recommended to me as exemplars of the course, and I was surprised in several respects. The unusual settings (in one segment Hays speaks from an upper tier in the GSD studio while students occasionally pass by in the background) elevated it beyond a traditional droning lecture in a dim hall, while the accompanying graphics made it immediately easier to grasp the concepts he described. The instant transcription on the side, which is a feature specific to the video when it's viewed through the Harvard portal, eliminates the need for note-taking (!). I sent Hays and Haber-Thomson these questions via email; the following is our unabridged exchange.

In the clips you sent me, your explanation of why Eisenman's Holocaust Memorial's abstraction works on so many levels is exquisite, and does rely on understanding complex ideas, many of which use jargon. However, would you agree that jargon can sometimes act as a kind of "Keep Out" sign to those who are unfamiliar with architecture, or may feel intimidated by the use of purposefully difficult language?

Like any field of study (such as science, medicine, and law), architecture has its own specific set of words and terms that convey uniquely architectural ideas. I believe the introduction of specialized language is enormously important and useful for scholars to develop new understanding The word “jargon” is often used disparagingly, and sometimes this judgment is warranted. However, I believe the introduction of specialized language is enormously important and useful for scholars to develop new understanding, as distinct from just conveying known ideas. When exacting scholars introduce difficult terms in a field-specific ways, it’s because existing words don’t seem adequate. For example, Wölfflin used the term “painterly” to describe the complexities of Baroque architecture as distinct from the linear clarity of Renaissance architecture, as an inaugural attempt to understand the new style. Other scholars took up the term and developed its meaning and articulated more precise components of the Baroque vision.

While at first the use of a term like this may have seemed strange and unnecessary, once introduced, it can be handed on from person to person, permitting the public articulation, criticism, and debate of ideas constituted by the terminology. “Jargon,” when used well, enables precise discussion. In this course, we’re using terminology established over several generations by architectural historians and theorists in order to speak specifically about architecture as a distinct cultural practice. We also introduced a specific model of the architectural imagination.

We further claim that any mode of knowledge is embedded in and limited by history; what can be known or thought at one time is not neccessarily available to representation at another timeOf course, difficult language can be exclusive. The reason one studies is to enter into this exclusivity. One of the biggest challenges we had in putting together the course was the unknowability of our own audience. One of our goals was to craft a course that was deeply rigorous in its content—we did not shy away from presenting difficult and complex ideas—but that would be accessible to a very wide range of learners. For those new to the study of architecture, this means an investment of time in the early lectures, where we spent considerable effort unpacking the specialized vocabulary that we could then use to better effect in subsequent lectures.

In your course, you situate imagination as the bridge between sensory data and understanding. You also describe architecture as acting as a representation of knowledge. This course is rooted in classical notions of knowledge, which is to say that the influence of religion on structure, as well as Greek and Roman architecture, often define how you describe the execution of this knowledge, especially in relationship to contemporary structures. I would argue that in the last few decades, the prominence of the hierarchy-free Internet, in combination with the waning influence of religions such as Catholicism due to scandal, has fundamentally altered how we collectively define knowledge. I believe that much of the so-called globalized architecture we see around us is in some ways a response to this influx of new information and new information delivery systems. Do you agree that due to the these relatively recent factors, how we collectively define knowledge may have fundamentally changed?

Yes, I would agree that we have different models of knowledge now. Knowledge is historically situated and constructed. The idea of the imagination comes in part from nineteenth-century German thought following Kant, which claimed that knowledge in science was an imaginative restructuring of the world in a way analogous to a work of literary fiction but according to different codes. That remains an important insight. Our claim is that architecture, too, is a mode of representing the world, one as fundamental for humankind as science or philosophy. We further claim that any mode of knowledge is embedded in and limited by history; what can be known or thought at one time is not necessarily available to representation at another time. The model of the imagination as mediator operating between our experience of the world and our understanding of it is enormously powerful.

With refinements to the model (which have been taking place in the theoretical literature since the late 1960s) we can accommodate an account of the sort of changes in information production and receptions that you mention. Though we do not address these complications directly in the online course, some implications are evident, I think, in the modules on the Pompidou Center, Paris, and the Holocaust Memorial, Berlin. The Pompidou Center is a vortex of economic, information, and corporeal flows; a viewer feels completely immersed and also completely connected to the city of Paris through an infrastructure of movement and information. In our postmodern global information society, the Center becomes a privileged locus of urban observation and commercial activity, analogous to what the Crystal Palace was to the nineteenth-century industrial society. Whereas the Berlin project is read as a symptom of a historical condition in which information tends to replace memory. In architecture, the mnemonic devices like monuments and memorials, which we normally use to stabilize memory, cannot carry the weight of the event of the Holocaust; the enormity of that event is not representable. And so the abstraction of the Berlin project presents the structure and processes of memory rather than trying to make a memorable, realist image. The attentive student will notice exactly the sort of transformations of knowledge you speak of across these two cases.

Perhaps another way to answer this question is to consider how we approached the medium of an online course itself. We are using this new medium to push back precisely against We are using this new medium to push back precisely against some of the problems of fixed thinking and rules that you described heresome of the problems of fixed thinking and rules that you described here. It’s important to note that we really think of this as a new kind of graduate-level course, not simply a series of recorded lecture videos or podcasts. A good deal of mental effort is required to benefit from the course. And the responses shared by the learners on the discussion boards show the eagerness and joy of that effort. What we’ve noticed is that an enormous range of people have actively participated—from all over the world, and from all different types of backgrounds.

The use of video and instantaneous transcription makes your course accessible to a very wide audience; in fact, it's possible to audit this course for free. What sorts of responses have you received from those who have taken it? Do they interact with the course in any noticeably different way than students who have taken the course in person?

One of the things we have learned from years of teaching beginning architecture students is that you must show your own sincere interest in the material you are lecturing about. If a student perceives that you think the material is important and enjoyable, the student is more likely to try to understand why. The decision to “produce” this course rather than just “youtube” a set of classroom lectures, as most other courses do, was a big decision This effort to engage the student is even more important in an online course because the course is not a requirement for a degree; rather you are competing for the learner’s leisure time. We have the advantage in the online course to use the video format itself to help us engage the audience. The decision to “produce” this course rather than just “youtube” a set of classroom lectures, as most other courses do, was a big decision, and we believe it has made a big difference in the audience reaction. Quick examples of what I mean by using the video format to advantage: My favorite is when the camera closes in on Lisa’s hands as she cuts up a Paris Taride map and switches around the pieces as I am discussing the Situationists International and their theory of détournement. Call it a gimmick, but it is enormously effective in adding movement, texture, and scale to what would otherwise be an onslaught of words, and is visually didactic insofar as it mimics the actual sort of means by which some of the Situationists’ works were produced. Another trick, which is almost unnoticeable, is to run the long shot of the walk through the Berlin memorial backwards. It creates a slightly uneasy feeling, an uncertainty without quite knowing why. There are also nods to a kind of material culture. When I quote from Le Corbusier’s texts, for example, the camera scans the actual page from the Oeuvre Complète. And we use vintage photographs where possible; there is a lot of black and white. And, of course, the vintage news footage of President Regan and Tom Brokaw is just stunning.

Our audience is surprisingly diverse, given the limits of the course topic. In addition to varying levels of education, we’ve also seen a very large global spread of learners. In fact, most of our learners are from non-English speaking countries. We think that, Most of our learners are from non-English speaking countries again, the video format works to our advantage. Learners tell us that they use pause and rewind and change their pace as needed; what might not have made sense on first hearing becomes clear the third time. Learners who need extra help with language are able to download transcripts and use translation tools and dictionaries. We have tutors to answer questions texted in from all over the world. We hope to expand the use of tutors in a slightly modified “high-touch” version of course next year.

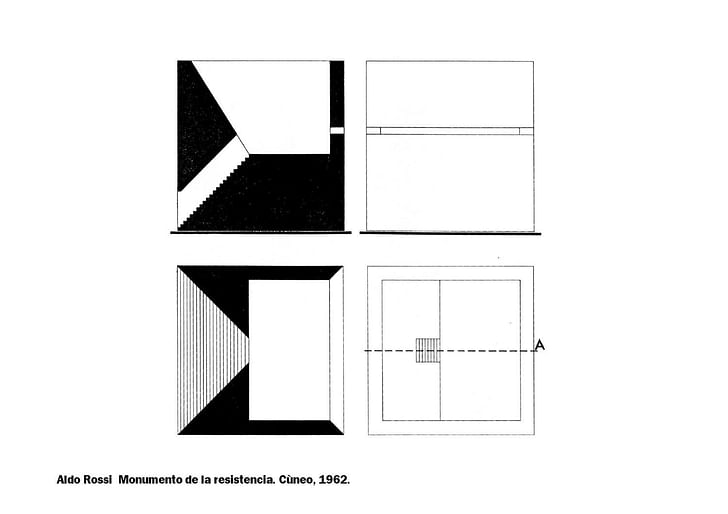

We also believe that learners who participate fully in the course, doing the readings and exercises, actually enjoy the course more that those who just watch the presentations. We spent a lot of time and thought building the “making-as-learning” exercises. Build a cardboard model of Aldo Rossi’s Cuneo Memorial and you will never again think of a cube the same way. Draw a perspective grid on top of a photo of Brunelleschi’s nave and you can better understand G. C. Argan’s thesis of representation, jargon notwithstanding, and thus better understand the Renaissance approach to space.

What is your favorite aspect of teaching? What is your least favorite?

My least favorite episodes in teaching are encounters with the assumption that historical material is irrelevant to our present lives. The fact is that one can know architecture only through its histories. This course has only one case study in the present century, but we feel the historical material prepares the learner’s imagination for alternative futures.

My least favorite episodes in teaching are encounters with the assumption that historical material is irrelevant to our present lives

What thrills me about this course is that it goes some way toward demonstrating certain benefits of an online format in the humanities. The online format first seemed to me to be destined for purely quantitative learning—for the mere conveyance of techniques and formulas. In contrast, teaching in the humanities, especially in what we might call the design humanities, requires constructing and performing knowledge, not just handing down what you already know. And we have found that kind of performative quality can be produced in an online environment.

Is there anything you would like to add or mention that hasn't been addressed in these questions?

I would like to add one point about the argument that led to this interview: the vexed notion of architecture’s autonomy. Critics have completely misconstrued the argument. The autonomy thesis asks the question: Does architecture engage society, and if so, does it simply reflect its technological and social determinants or does it contradict, distort, resist, compensate, or in some way reconstruct those determinants? The premise of this course is that architecture is deeply embedded in history and society, but it represents social values in its own architectural way. By giving architecture a degree of autonomy we are able to show the projects not as passive and inert products of empirical forces but as active agents in complex historical contexts and events.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

70 Comments

On verbiage, I find Choamsky's criticism of Derrida to be particularly refreshing:

"So take Derrida, one of the grand old men. I thought I ought to at least be able to understand his Grammatology, so tried to read it. I could make out some of it, for example, the critical analysis of classical texts that I knew very well and had written about years before. I found the scholarship appalling, based on pathetic misreading; and the argument, such as it was, failed to come close to the kinds of standards I've been familiar with since virtually childhood. Well, maybe I missed something: could be, but suspicions remain, as noted. Again, sorry to make unsupported comments, but I was asked, and therefore am answering.

Some of the people in these cults (which is what they look like to me) I've met: Foucault (we even have a several-hour discussion, which is in print, and spent quite a few hours in very pleasant conversation, on real issues, and using language that was perfectly comprehensible --- he speaking French, me English); Lacan (who I met several times and considered an amusing and perfectly self-conscious charlatan, though his earlier work, pre-cult, was sensible and I've discussed it in print); Kristeva (who I met only briefly during the period when she was a fervent Maoist); and others. Many of them I haven't met, because I am very remote from from these circles, by choice, preferring quite different and far broader ones --- the kinds where I give talks, have interviews, take part in activities, write dozens of long letters every week, etc. I've dipped into what they write out of curiosity, but not very far, for reasons already mentioned: what I find is extremely pretentious, but on examination, a lot of it is simply illiterate, based on extraordinary misreading of texts that I know well (sometimes, that I have written), argument that is appalling in its casual lack of elementary self-criticism, lots of statements that are trivial (though dressed up in complicated verbiage) or false; and a good deal of plain gibberish. When I proceed as I do in other areas where I do not understand, I run into the problems mentioned in connection with (1) and (2) above. So that's who I'm referring to, and why I don't proceed very far. I can list a lot more names if it's not obvious."

To be completely fair to KMH, he should not be wholly wrapped in the above criticism and is not trying to be obtuse or difficult with his extensive use of needlessly complicated rhetorical constructs and verbiage; he simply does not have enough distance to unpack contemporary architectural theory in simple, easy to understand terms. Again, not his fault, and he should be lauded for producing this course--its not like he needs the money or fame from a side project. Its my understanding that KMH genuinely wants to bridge the gap between theory and public discourse.

Bravo. But its clear we still have a long way to go

As someone who studied architecture in the early 1970's when international modernism still held sway, the social idealism of the movement (while admittedly overly grandiose and misplaced) meant that the language of theory and the language of practice had substantial overlaps. This meant that I could take what was discussed in academic circles and repeat the same kind of language in contexts of practice and be understood. Now, ever since the post-modern destruction of overarching narratives, the two languages are completely distinct and polarised into separate spaces: theory in academia and practice in firms. Deprived of philosophical foundations, any aspiration in the language of practice has to take recourse to strategies of branding; and if the architect is already an established brand, then no language is required, only seductive imagery is called for. And the language of theory has become so esoteric that if I, as an architect who has not achieved status as an iconic brand, were to attempt it in practice my client's eyes would probably glaze over wondering who this weirdo architect is who has been hired for the project.

I mentioned this in a conversation with Michael Hays a couple of years ago, and he acknowledged it as a problem to which nobody has come up with an adequate answer.

A part of the problem is that architecture has become a self-referential community. Any activity that has substantive intangible goals relies on some form of social validation. In architecture, this has taken the form of assessing whether the work wins major awards, whether it is published in reputed journals, whether it wins competitions, whether it is discussed with respect in the major architecture colleges, or whether it offers recognition as a speaker on the lecture circuit. These are all valid goals, but they are all frames of peer review, and when they become the dominant reference it breeds a culture where architects design primarily for other architects and lose the ability to talk about value in architecture to those who are not architects.

The answer probably lies in reconstructing the sociology of practice rather than coming up with another good theory or philosophy. I like to phrase this by saying we have spoken enough about the practice of architecture, and we must now turn our attention to the architecture of practice.

>A part of the problem is that architecture has become a self-referential community.

The discipline is incredibly self obsessed, while being ignorant and uncaring of progress being made outside the field. I'd be interested in hearing more about the architecture of practice

Honestly English is a simple language with a relatively small vocabulary- no wonder then when trying to explain anything relatively complex others cry about "jargon".

I wish this course was in a different language from a non American university. It would be interesting to see the perspective of the History of Architecture from another culture and the words they would use to describe it. Besides with the rate of building in places outside English speaking nations it would make sense to see the world from their perspective.

Being an English as a second language person I talk and write with a relatively smaller vocabulary. But that is not an excuse to ask people write the same way. Architecture speaks a specialized language and if you want to understand what they are talking about or written, you better work on it. I am not talking about familiar and pretentious "jargon" though. There is no way someone like Hays would speak jargon. Btw, it takes a lot of work to write with an everyday common vocabulary but one tends to remedy that with something entirely different.

I gave the course a try but it just reminds me how much I hated architecture school bs. The content is totally irrelevant to architectural production today.

Any ideas on this?

http://sciarc-offramp.info/tolerance/graham-harman

Phenomenal example of why non architectural theorists should be given preference on the subject over practitioners. In the arena of architectural theory, quality scholarship that directly engages primary sources is a breath of fresh air.

but, be careful when architects start to literally turn the ideas to buildings. remember, de-construction finally hit the convenience malls, not in a good way either.

The idea that the AIA is trying to become more diverse does not preclude the use of jargon, and may actually require that it embrace more of it. If you are trying to expand your field of knowledge, drawing from other resources you need to bring those actionable terms into your (properly) discourse. Intersectionality, Colonialism, and Blackness as examples are critical discourses that need to be understood through with respect to how they impact architecture as discipline before the architect can become the interlocutor through spatial manipulations.

I for one suggest we spend at least two more semester in school studying intersectionality and how it might effect our subconscious biases in design and our understanding that all architecture is the construct of violent European colonialism, and less time studying how to build buildings which students can learn on-the-job anyway. Giving students the skillset to learn how to think is a more effecient use of their tuition money than teaching them construction principles they can learn in their internships.

The real danger for the pedagogy, and for the profession as an extension, is when buildings derived from these ideas cannot appeal to the public. It's fine for architects to speak to each other in arcane language, but that is only one level of meaning. If they cannot communicate in other modes, including the emotional, visceral level, connecting to people who are not imbued with "inside knowledge" of architectural theory, then our buildings become dry, obscure, and the profession drifts further away from humanity.

To follow up on this point, I was reminded of the 1982 debate at the Harvard GSD bettween Christopher Alexander and Peter Eisenman. A great read if you have never run across it. They really represented two important, opposing worldviews, taking shots at each other across a vast ocean. This quote from Alexander is really germane to the current discussion:

Nah man, architecture needs to tell its clients what they want, not listen to what they think they want. Schools should do everything they can to teach students to learn how to learn so that they can teach clients how to learn. Let's get more obscure texts in studio and less construction knowledge. Learning how buildings are built and how to attract clients is what students should learn in their internships after graduation. School is the time to promote ideologies.

If you are designing for people, why wouldn't you consider what their preferences are, and try to address them?

James, I guess it comes down to what the purpose of architecture is.

By the way, I agree that school is the time to immerse ourselves in ideologies....but some ideologies are better than others. :)

Interesting thread! And, fortunately, it doesn't have to be one or the other, abstruse jargon or transparent prose. It is possible to do both, or close to it.

My sense is that two things are at work in this arena: 1) time, and 2) audience.

Explaining complex ideas using particular nomenclature can be accomplished with some level of clarity and accessibility for the (reasonably aware) newcomer. But this takes time. (Good writing is rewriting, someone wise once said.) And many authors, possibly brilliant, often just don't take the time and effort to phrase, rephrase, reorder, refine, and generally do what it takes to craft (and re-craft!) a well-written essay. I'd offer that shaping a good, clear narrative is every bit as challenging and time-consuming as designing a good building.

Elsewhere, some "brilliant" minds appear far less interested in enlightening the average reader than they do impressing their small cohort of colleagues and competitors in academia. (We've all seen this ugliness on display in miniature at school reviews, where some windbag forgets about the poor student as he works harder and harder to impress the critic in the next chair.) And if the target audience is indeed tiny in number as well as fully schooled in the rarefied lexicon, God help the rest of us mortals trying to slog through the material.

Obviously I'm referring to written work here, but I think this generally applies to presentations as well.

To follow up on this, I was reminded of the 1982 debate at the Harvard GSD between Christopher Alexander and Peter Eisenman. http://www.katarxis3.com/Alexander_Eisenman_Debate.htm A great read if you have never run across it. They really represented two fundamental, utterly opposed worldviews (they call them "cosmologies"), very Platonic in their polarity, taking shots at each other from across a vast ocean. Although he was talking about the then-current trends of Structuralism and Post-Modernism, this quote from Alexander is really germane to the current discussion:

"...Of course, I think there are people who are very serious, and want to move the many with the privileged view of architecture that they have in their heads. But words are very, very cheap. And one can participate in intellectual discussions, right, left, and center, and you can go this way or you can go that way. Now then, I look at the buildings which purport to come from a point of view similar to the one I've expressed, and the main thing I recognize is, that whatever the words are -- the intellectual argument behind that stuff -- the actual buildings are totally different. Diametrically opposed. Dealing with entirely different matters."

"Actually, I don't even know what that work is dealing with, but I do know that it is not dealing with feelings. And in that sense those buildings are very similar to the alienated series of constructions that preceded them since 1930. All I see is: number one, new and very fanciful language; and two, vague references to the history of architecture but transformed into cunning feats and quaint mannerisms. So, the games of the Structuralists, and the games of the Post Modernists are in my mind nothing but intellectualisms which have little to do with the core of architecture. This depends, as it always has, on feeling."

^ Excellent.

great that you did this Julia. Also very impressed that Michael Hays and Lisa Haber-Thomson agreed to the exchange. That speaks a lot about them, and deserves a lot of respect.

I was almost convinced that I had it wrong until the end, when the main critique that stung Hays to begin with, is raised again. His/their final comment is (ironically?) autonomous and safely set aside from either self-reflection or the reason the approach is critiqued to begin with. An unintended proof that autonomy removes architecture from society rather than engage with it, regardless of the intent.

Architecture of our time is about engaging with outside streams of thought/knowledge. The project of autonomy, and the distancing verbiage that goes with it, makes that harder. The value of history is unquestioned, but this idea that we should be so aloof feels out of place. It devalues us. The position also explains why Linkedin keeps sending me jobs in IT companies. We are losing even our ownership of the word architecture by pulling in the drawbridge this way.

"We are losing even our ownership of the word architecture by pulling in the drawbridge this way."

Check the Oed and you'll see that the 1st time architecture is referred to in computer science was the early 60's- taking advantage of the concept that architecture provides the framework for operations, activities, and events. While this was going on, architects and ecologists were trying to reconcile themselves with the concept of cybernetics, resulting in energese and bubble diagrams.

Neither side "got it right," but by embedding that jargon into their own discourse opportunities were created to expand the boundaries of thought. I think it is ok to loose ownership because the expansion of the term only creates additional avenues of thought.

And frankly, it's just not appropriate to run around chiding people who do not practice architecture from using the term while at the same time proclaiming you know what makes architecture "woke."

In the debate between Alexander and Eisenman, my sympathies would lie with Alexander. But the later Alexander of "Nature of Order", and not the early Alexander of "Notes on the Synthesis of Form" or the intermediate Alexander of "Pattern Language". But even with the later Alexander, I sense he is someone who takes his theory far too seriously, and believes all answers can be found there.

The challenge is to relook critically at the relationship between theory and practice, and there is a problem in looking at them as discrete separated activities performed by different sets of people in separate spaces. In this model, theory is foundational and subsequently 'applied' in practice. Theory then seeks to be something that is complete before it finds its way into practice.

The relationship is more complex and nuanced. The two cover the same territory but in opposite directions.

Practice moves from the general to the specific. I start with something more general, like a design challenge. I then come up with conceptual possibilities, then zero in on one to be executed, then start detailing it out, looking at its constructability, and so on. In the process, I move further and further to greater detail, and if I do nothing but that, my centre of gravity as a person starts moving toward detail, and I become the 'nuts and bolts' architect.

Theory, in contrast, moves from the specific to the general. It starts with specific observations, and then seeks to ask what they mean so that general principles can be extracted from them. Here the process moves to greater levels of abstraction, and if I do nothing but that my centre of gravity moves to the level of abstraction, and I become the 'ivory tower' academic.

So the two work best when the contradict each other: theory is a means of critiquing practice, and and practice is means of critiquing theory. In this conversation, one maintains a critical balance as a person.

We have not looked enough at how the construction of the self is implicated in the production of architecture. In the critical conversation between theory and practice one aims to construct a more complete self. Separating theory and practice leads to the construction of fragmented selves. Theory, as a thing in itself, tends to separate the thinking self from the feeling and experiencing self. And practice, as a thing in itself, tends to separate the economic and experiencing self from the thinking self.

I am not arguing that everyone has to be simultaneously a theoretician and a practicing architect. But every theoretician requires some form of practice that critiques theory, and every practicing architect needs some form of reflection that critiques practice. For this, we need more situations where theory and practice are made to co-exist in the same space. While we are asking what theory and practice are, we must also ask where they are.

A model that sees them as incomplete in themselves, which insists on their critical conversation, would then realise that learning is a product of both thinking and doing. For a wonderful and poetic description of learning through practice, see Martha Graham's delightful essay "An Athlete of God" at https://thisibelieve.org/essay/16583/

I have also investigated this question in an essay, for which the abstract can be seen at https://tinyurl.com/y8dboen2

Regarding the Aaron Betzky article Marc posted, I'd simply refer to the Christopher Alexander quote I posted.

The Alexander quote is brilliant. Choamsky even better.

@Marc, I have no problem with other people calling themselves architects of whatever and the Linked in thing is more funny than anything. My problem is more about the archi-babble thing and what that means for us as a profession. It reinforces distance from reality, both from practitioners and from those whom we hope to serve.

It gets too much when even banal buildings are wrapped in mysterious words that are clearly pointing at nothing at all. Why teach people to think this is what architects do to begin with? It is not helpful. It isn't as if the words are hiding particularly deep theories nor that speaking plainly makes it hard to communicate difficult thoughts.

I think we agree to a point because I think some of that babble that is not architectural, but social or political generated outside of architecture is real and architecture could benefit from it. I'm also wary of the babble we have created and accept as normal. There's a lot of implicit jargon architects love to throw about, but when it's new...

I'm surprised that no one is siding with Eisenman. I thought that the good points of the autonomy argument had been absorbed by now...

In that 1982 debate, the way I remember it, Alexander says that above all architecture should be "good" - that architects should contribute to a comfortable and well-functioning environment. Sounds nice, but Eisenman makes a good point: he replies that "boring" architecture is not really architecture - architecture is always provocative in some way, it stands out from the background of the everyday built environment. He had in mind architecture that deliberately makes people uncomfortable, but you don't need to go that far. And it doesn't have to be one or the other (a building can be functional _and_ provocative). I would agree that all "great" architecture makes a statement or "reflects social values" or does something unusual with space or movement or ornamentation. A work of architecture is more than just a good building. The whole point of "autonomy" is about trying to specify all the things architecture can do beyond being functional/comfortable/good.

I can see why architects would want to focus on just making good buildings, but every architect I've met is more ambitious than that. It's what every architecture student asks themselves: besides just making a good building, what can I do with architecture? Or to put it in the terms of "autonomy:" what sets architecture apart from everything else? To use one of the first examples that Hays brings up in the course: looking at Palladio's villas, you could say that the layout and proportions of rooms somehow embody humanist values. Thinking about architecture in terms of its autonomy means thinking about the range of things that are unique to architecture. It might be some kind of public symbolization, spatial perceptions or feelings of different kinds, the relationship of a building to its immediate context or the city, the relationship of building to human body, or other things. The point is not to talk about particular cases, but to generalize from them. What are the "effects" that are unique to architecture? When Loos says that a mound in a forest (under which someone is buried) is architecture, wherein lies the "architecture-ness?" It's a basically philosophical question, so it requires difficult abstract language. But these are things architects are always thinking about anyway, not some academic hogwash.

Peter Eisenman gives the example of the columns of Moneo's Longrano Town Hall (http://images.adsttc.com/media/images/5568/c18a/e58e/cea4/d100/0001/large_jpg/14042769362_802d7aa121_h.jpg?1432928645), which he says make people uncomfortable. Adolf Loos's example of the way coming upon a burial mound in the forest sends chills down your spine is also a good on. But basically the idea comes from Russian Formalism: it's about "strangemaking" (see Jameson, The Prison House of Language). It's also often called "thematizing," and some art critics think it's what art is supposed to do... (e.g. https://www.gc.cuny.edu/CUNY_GC/media/CUNY-Graduate-Center/PDF/Programs/Art%20History/Digital-Divide.pdf). This is all stuff that has been central to art and architecture (of the formalist persuasion) for at least a hundred years. I don't think it's the end-all of theory, but there are some important points in there.

Jeffrey Kipnis likes to argue that the threshold is one of the things that is "uniquely architectural." He also makes tends to make the argument for autonomy pretty straightforwardly. Maybe this: https://vimeo.com/70166956 ?? I haven't seen it, but he tends to repeat the same lines

I would agree with Eisenman on the autonomy of architecture as well as the demand that the architect should not be content with being good but should also be critical. But the reasons for this would probably differ considerably. I sense that Eisenman is claiming a didactic role for the architect. This is dubious on ethical and political grounds. On what basis does the architect claim this unique privilege of being publicly didactic? The autonomy of architecture is necessary so that architecture can maintain its sense of being a discipline. Without this autonomy, architecture is forced to borrow from many other disciplines: art, logic, philosophy, linguistics, sociology, and so on. There has been so much of this borrowing that architecture has a existential crisis in defining itself. This autonomy is based on the nature of space, for the ordering and enrichment of space is a task that only the architect takes on. But is this autonomy a thing that is complete in itself? And here I would say no. I pick up from Juhani Pallasmaa’s statement in The Eyes of the Skin, “In the experience of art, a peculiar exchange takes place; I lend my emotions and associations to a space and the space lends me its aura, which entices and emancipates my perceptions and thoughts”. We use the autonomy of the discipline to construct an aura, but it is the dialogue between the aura of architecture and the inhabitant that makes architecture meaningful. David Heymann makes a similar argument in his essay A Mound in the Wood, (https://placesjournal.org/article/a-mound-in-the-wood/) using the arguments of Adolf Loos as well as some imperatives in landscape architecture, to argue that most architects privilege interpretation as coming before experience, but it should really be the other way round. I read Heymann and Pallasmaa much later, but started exploring this idea twenty years ago, arguing that meaning is something that accrues over time through experience and memory within architecture. That should lead to a different kind of aesthetics in architecture: one that is gradually absorbed into the work, an aesthetics of absorption. Architects are schooled in an aesthetics of expression, a didactic role that privileges the architect’s intentions as the primary generator of meaning in architecture. If you are interested in seeing that twenty-year-old essay, see https://tinyurl.com/yarut93j If we take a critical role towards architecture, it is not because we are privileged social critics, but because we are interested in uncovering new possibilities, are not content with merely promulgating the status quo, for our profession involves an ethical obligation to critique the status quo for its shortcomings.

"architecture that deliberately makes people uncomfortable" is a failure from the very concept.

premckar, I honestly don't see what's so bad about being didactic. yes, it can come off as heavy-handed, but it's a valid tactic in the architect's repertoire. just because a building "says" something or makes a point doesn't mean people need to listen. i do agree with you that claiming the "unique privilege of being publicly didactic" is dubious, but only because it's presumptuous. autonomy can trip up on hubris. that's something to be solved by adopting humility; it's not a sound reason to throw out the whole argument, in my opinion.

Mathew. While it would be foolish to demand that one should never ever be didactic, I am troubled when it becomes the dominant goal (which it unfortunately does far too often in what is perceived as the cutting edge). Leave aside the tendency toward hubris, which you feel could be overcome through humility (not sure about that, but that is another discussion). But if the primary meaning in architecture is seen as didactic, and architecture carries a message from the architect, this is problematic in the way architecture is experienced. Most architecture is intertwined with the regimen of daily life: people come to the same building day-after-day, year-after-year. How does the message survive the boredom of incessant repetition? If being didactic is just one tactic in the architect's repertoire, it needs qualification of contextualisation in the range of other tactics, and the question of which tactics should have primacy.

I entirely agree with you regarding the relative importance of experience vs. communication in architecture (to use slightly more neutral terms). Most parts of most buildings most of the time should be comfortable and well-functioning. The only thing I would want to emphasize is that I think architects and their buildings can do many things at the same time. Normally, some amount of facade-work is given over to expression (or didactics) while most of the interior is more conventional. The best architecture, in my opinion, is provocative, surprising, and strikingly beautiful at the most opportune moments, but then fades into the background to become flawlessly functional. The genius of the architect is being able to pull off different (even seemingly contradictory) effects in the same work. So I don't go along with Eisenman very far (and, as someone else also commented, I think his buildings often strike a better balance than his writing would suggest).

I haven't rad this thread but want to point out that on NPR this morning, in a discussion of the Grenfell Tower fire, the host and interviewee had to define what the word "cladding" means.

And there you have it @Donna Sink. "Cladding" gives the public pause. I propose that there are and have always been three languages of Architecture. They happen to correspond nicely to the audiences of architecture:

1) The language of the discipline; e.g Michael's imagination; Jorge Silvetti's shadows; Eisenman's Autonomy, Gideon's canonical facts, mannerism, structuralism, this entire thread, etc.

2) The language of the practice; e.g cladding, B101, bi-lateral symmetry, etc.

3) The language of the public: e.g. form vs. function, Gideon's transient facts, everyday life.

There is PLENTY of room for the languages to cross over from time to time at the service of the public, the practice and the discipline. Whether or not they should all congeal into a single common tongue is the question. I am of the opinion that they should not. Serious students of architecture, that is those who might attend university, take the Hays course, or exhibit sustained interest in the subject otherwise, will recognize the trifecta. All of these student SHOULD be taught to understand the distinction and interdependence of the languages. But we should be very wary to replace the language of the discipline, which provides our history, specificity and conceptual clarity, with the language of the public that is often a necessary but transient fact".

Nice thought about separation (ASHREA is jargon).

I agree that the languages of the discipline, practice and public are not the same; and it would be unwise to seek to collapse them into a single language. But doesn't this impose an obligation on the architect to be multi-lingual?

yes, exactly - we should all aspire to be multi-lingual

Just for the fun of it (procrastination?), here are two lists of jargon, or lessons on twisting language. The subtle differences are interesting.

BIG The 8-House

common architectural species villa

House (by way of translation) urban cell split

campanile (historic reference) monolith

Appendix Architectonically

“same formal language as a crushed milk carton” facetted triangular gable motif

facade cosmetic variation

urban layer cake architectonic symbiosis

knot continuous mountain path

inner void orgy of various spatialities

Rem Koolhaas - The Future Of The Way We Live, Love And Work

zeitgeist Domains

Solidity Provisional

concentrations of color dysfunction

functionalities countryside (or landscape)

Spectral Complexity territory

apparatus virginal territory

inert boxes contemporary sublime

(Metaphors Koolhaas suggests are being stolen)

Architect Arena

Blueprint Construct

Platform Pantheon

Framework Theatre

Stage Sphere

Structure Facade

Based Foundation

Model Board

Block Arcade

Buttress Scaffolding

International Style

It's important to recognize the difference between jargon and technical language. One has a critical, functional place in and is critically important to design and construction. The other is often presented as philosophy that deliberately ignores function, practicality, or even clear communication.

Much of this emanates from the "top" of the profession where starchitects compete against each other with theories of aesthetics that are essentially marketing tools. These are often meaningless nonsense and even self-contradictory once analyzed (Schumacher is a vivid example).

The Emperor's new clothes come to mind.

How about-

facade,

elevation,

parti,

and section

Just browsed the 'parametric shakedown' article here looking for a PS quote but could not select one from the embarrassment of rich examples.

http://archinect.com/news/article/86857898/parametric-smackdown-patrik-schumacher-and-reinhold-martin-debate-at-calarts-conference/

I witnessed Patrik tell a civil rights layer that the voting rights act is a useless piece of legislation.

the idea that architecture should be uncomfortable in some way is something I would absolutely agree with. It is the only way to work. Mcmansions and pastiche are comfort food. I won't say they should not exist because variety is the spice of life, but it is not the realm i would like to work in. That is not a communication choice though, its about what kind of art I like.

Eisenman never really needed to write about his work though. The work speaks for itself. He chose to write a lot because he felt compelled to. Gehry didn't and that was fine too. Both built careers on making people think about the built world in new ways. It is a path that I can appreciate. It falls apart when theorists try to write about it and don't want to compare what is in front of them to deformed milk cartoons or whatever. This is the part that I don't understand. Why make challenging ideas more complicated than they already are?

My suspicion is that they are afraid to speak plainly because plain people might speak back. And that is scary.

What about buildings like, say, the NY Public Library, or FLW's Robie House. These are buildings that are nearly universally praised as great architecture, and are loved by the general public. They are buildings designed by architects who held being "uncomfortable" to be very, very far down on their hierarchy of values. Are they "comfort food"?

FLW's work is not exactly comfort food. Its very refined and challenging. Famous for it.

I can imagine a gradient from pablum to challenging design and prefer the challenging work over the pablum. FLW is definitely not close to a mcmansion on that sliding scale.

The definition of challenging architecture is not really about how to talk about architecture though. Hays and his generation were/are very smart people trying to place architecture in privileged position through words. I don't believe it works.

Do you think that FLW set out to make people "uncomfortable"? I don't think so. If his work can be said to be "challenging", it's perhaps because he was exploring new formal languages in a sophisticated way, but I believe his goal was to create beauty. I think that is nearly the opposite of trying to make people uncomfortable.

Let me ask this another way. Do you think it's possible to produce sophisticated, challenging architecture that does not try to induce discomfort in those who experience it?

FLW didnt really care if people were comfortable. His bio makes that pretty clear. About making challenging architecture and discomfort, the answer is in the question. To be challenged by anything is to be placed in a position of discomfort. So no, it is not possible. Discomfort does not mean glass on the floor though. It means not knowing what to expect. That might be awe-inspiring for some, horror for others. It is the reason the idea of universal or classic design cannot be a thing.

I live in Japan, in Tokyo, and have been lucky enough to visit most of the classics, contemporary or otherwise, that litter the city. The glass box homes of Sejima and Fujimoto are amazing, and would be fine for me to live in but when I go there the windows are covered with closed curtains and in some of Fujimotos designs the glass is entirely covered by white film. Every piece of glass, on every facade. When I visit the Netherlands I can find 2 story high glass facades and people are eating breakfast or whatever and couldn't care less about who looks in. The way the architecture challenges someone depends on who is experiencing it. Psychology makes it difficult to generalize.

I've read Wright's biography, and I'm not sure I agree. It's certainly true when it came to furniture, where form was definitely more important to him than comfort. But I think that's a lot different than having the goal to make people uncomfortable.

Maybe we need to define "discomfort" in this context. I think its a fundamentally different thing for Warren and Wetmore to create a sense of "awe" when you walk into Grand Central Terminal, and for an architect like Eisenman of Libeskind to create buildings that are designed to disorient and irritate. I believe that the distinction between the two is important and fundamental.

"FLW didnt really care if people were comfortable"

'The architect should strive continually to simplify; the ensemble of rooms should be carefully considered that comfort and utility may go hand in hand with beauty' - FLW

(among dozens of other similar quotes of his)

To build a little on my previous post:

Publications:

The language of the Discipline: Log, Oppositions, some parts of Archinect.com

The language of the Practice: Architect Magazine, Detail, Domus, El Croqui, most of Archinect.com, Journal of Architectural Education,

The language of the Public: Dwell, Architectural Digest, Times (NY & LA).

_____

Explanations:

Discipline: Precedent, Critical Thinking, Philosophy, Architectural Criticism from Within, Syntax, Linguistics

Practice: Formal composition, technical detail, building codes, ASHRAE, LEED,

Public: Metaphor, inspiration, $/sf, green hyperbole.

_____

To be certain there is JARGON in each language. Jargon can be spoken "plainly" but that is RELATIVE to the expertise and specific jargon adapted for each language in question. But again, replacing the Jargon of the Discipline with the Jargon of the Public is certain to be fraught with further incoherence.

^ very well said

There are so many layers to this discussion. The jargon used by KMH (and other names mentioned here) is not only a sorry attempt to mask an intellectual and epistemic vacuum of which he seems to be the last to know, but it is also to mask the vacuousness of the program that he leads (the tiny PhD program with which I am fairly familiar). More importantly, this jargon is a sad and thinly veiled cover-up for ways of thinking about architecture that are steeped in antiquated, or more accurately obsolete and morally bankrupt, theories created at the heart of a capitalist, imperialist, colonialist, racist, and self-obsessed Europe (KMH's claim to be interested in "critical theory," demolished in the late 1990s, is another cover-up for his essentially Hegelian and bizarrely Christian leanings; anyone remotely associated with the Frankfurt School would be appalled by what he advocates, especially the deliberate obfuscation and dilution of serious political, social, or economic issues in which architecture is imbricated). KMH can learn a lot from walking a few steps down the road to his colleagues (for him, more like archenemies) at MIT, who are calling for a global and culturally-inclusive ways of thinking about architecture that essentially aim to generate new knowledge rather than continuing to spew out irrelevant, misleading, and grossly self-referential stuff (cannot get myself to call the stuff that KMH produces "knowledge"). This is not to say that those at MIT or other progressive schools are saints or that they are more in tune with practice (far from it), but they are at least attempting to move history and theory forward. What KMH and his kind are doing is not only holding history and theory back and increasing the schism with practice, but also doing such harm to architecture itself and its credibility and agency.

Amen -- and you flatter me.

I'm going to suggest this is the value and power of autonomy (just to stir the pot). This self-important lens and it's "capitalist, imperialist, colonialist, and racist" obsessions are perfect devices to reflect upon society/culture and class (remove oneself from the context and comment ). But without it modernism as a project cannot support itself, throwing architecture - one of the original liberal disciplines - into crisis.

archibabble - I forgot all that BS when I wwnt to work at 'Skidmore, all the Ivys there would talk that way, I didn't need to, I was just a grunt

The more bizarre the jargon the more bizarre the work. The holocaust museum pictured above being exhibit A. It looks like a supply staging area for a really big dam or something. What should have evoked hope and transcendence of the human spirit is totally missing. Epic fail. Not only that the concrete blocks are already falling apart.

For those interested in theory in a different mode:

http://www.sacred-space.net/2018walton-event/description.pdf

http://www.sacred-space.net/2018walton-event/program.pdf

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.