Archinect's Deans List is an interview series with the leaders of architecture schools, worldwide. The series profiles the school’s programs, pedagogical approaches, and academic goals, as defined by the dean–giving an invaluable perspective into the institution’s unique curriculum, faculty, and academic environment.

For our latest installment, we spoke with Winka Dubbeldam, Miller Professor and Chair of Architecture of the Weitzman School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania. The Weitzman School is home to a range of academic design programs—including focuses on architecture, city and regional planning, fine arts, historic preservation, landscape architecture, and urban spatial analytics—and to a collection of think-tanks and research centers, including the Green New Deal and landscape urbanism-focused McHarg Center.

In our conversation, Dubbeldam, who is also a founding principal at Archi-Tectonics, highlights some of the latest research and academic endeavors at the Weitzman School, including the school's new advanced research and innovation lab, innovations in design deliverables, and how the school hopes to integrate recent technological leaps into the design and fabrication process.

Briefly describe your pedagogical stance on architecture education.

We at the architecture department at UPenn have been experts in digital design and 3-D digital printing since the mid-nineties. Penn was already deep into the digital design and research, and was one of the first to develop this in the classroom. I started teaching a fully digital, paperless design studio with Maya software at both UPenn and Columbia University in that period. Moving forward! Now that digital design is the norm, and has reached a plateau from which we can deepen the research, push the design boundaries further and evolve into a robotic and more advanced digital printing techniques, I believe that it is also the time that it can reach a more complex, deep, integral approach combining excellence in design with expert input in technological, material, environmental, and theoretical knowledge. I strongly believe that the use of the advanced digital tools allows for and actually facilitates the blurring and erasure of the boundaries between design & technology. Students easily work across digital platforms and we teach them how to integrate the former academic pillars in one large, complex whole.

Our conference a few years ago The New Normal investigated this in depth, and we are excited that next Fall we can continue this as we are hosting Acadia 2021: Hybrids & Haecceities, which asks how technology enables, reflects, and challenges established disciplinary boundaries and design practices. Haecceities describes the discrete qualities or properties of objects that define them as unique, while Hybrids are entities with characteristics enhanced by the process of combining two or more elements with different properties. Hybrids & Haecceities aligns with a fundamental shift away from abstract generalized models of design and production towards custom or bespoke design now possible at an unprecedented scale due to Industry 4.0. This mode of working enables more diverse and considered forms of embodied, situated means of engagement with the world. Concurrently, the fourth industrial revolution risks unparalleled levels of consumption that will produce profound global effects with significant social, political and economic and environmental impact.

What insights from your past professional experience are you hoping to integrate or adopt as the Chair?

Being from Europe and having taught at Columbia, Harvard, and UPenn, and having had intense collaborations with the MIT Media Lab, I am probably equally inspired by all. My approach to teaching is guided by a strong belief in collaboration and dialogue and working with peers, through world-renowned faculty including Marion Weiss, Thom Mayne, Wolf Prix, and Joan Ockman, among others, as well as through other external experts and academics. Annual symposia allow us to be good hosts and invite our peers to present, facilitating dialogue and collaboration. Our students benefit enormously from being exposed to great speakers and lecturers. I also realized that we could better share our findings through publications, and I immediately initiated the Pressing Matters annual publications, now published by ORO publishers and designed by WSDIA.

Now already 7 years in, I hope that some of the effects of my leadership are starting to show. Between growing the program and doubling the standing faculty, while restructuring the curriculum to adjust to the practice’s new future of integral design and FTF [file to factory] manufacturing, it’s been an intense ride.

What kind of student do you think would flourish at UPenn and why?

I feel that our way of educating really does not discriminate which type of student would flourish at the school. Any student with or without an architecture background who is willing to work hard will be successful at Penn and, eventually, in the practice. We value that our students are independent strong thinkers and express themselves generously.

The department of architecture aims to provide an international, interdisciplinary design education that is geared towards excellence in design, rigorous research, and social equity. We pride ourselves on being on the forefront of digital design, 3D manufacturing, and robotics, and excel through the inclusion of external experts through annual

symposia, weekly lecture,s and regular design reviews. Our precisely balanced education gives a thorough, in-depth architecture training that sets the student up for success.

Now that digital design is the norm, and has reached a plateau from which we can deepen the research, push the design boundaries further and evolve into a robotic and more advanced digital printing techniques, I believe that it is also the time that it can reach a more complex, deep, integral approach combining excellence in design with expert input in technological, material, environmental, and theoretical knowledge.

What are the biggest challenges, academically and professionally, facing students today?

Right now, we are amidst a hopefully once-in-a-lifetime COVID-19 situation. It has only highlighted the overexertion of the earth’s resources, population density, greed, and immense global pollution levels. It will have lasting economic, cultural, and social consequences which will result in an altered state after the social distancing slows down, and the economy and social life starts back up.

But having said that: these ongoing global pressing issues, which affect us all, is why we do not just train our students to be excellent designers and architects, but also on how to be researchers, analyzers, and critical thinkers ultimately educating them to be future leaders.

Architecture is experiencing an extraordinary renaissance in the practice, fueled by many different sources: new technologies and materials; information technology; advances in engineering and manufacturing; globalization of culture, education and practice; crossovers with the sciences, visual arts and other design fields; a growing audience for design culture in general, and ecological

architecture in particular; and a focus on creativity and innovation in leading schools around the world. At the same time, society faces many challenges, including global warming and environmental change, pollution and waste, transition to new energy and resource economies, the redistribution and reorganization of political and economic power worldwide; globalization of the construction and development industries; population growth, shrinkage and migration; urban intensification and attrition; privatization of public sector activities; and the transformation of cultural identities and social institutions. We seek to bring the expansion of expertise and creativity in architecture to bear on these challenges. In this context, we will formalize our identity as a laboratory for ideas, expertise and innovations, a think tank for exchanges and debates across disciplinary boundaries, and one of the centers engaging a growing audience and international network.

What are some of the advantages of the school’s context—being at UPenn / the Weitzman School and in the Philadelphia metropolitan region—and how do you think they help make the program unique?

Philadelphia is a great city, with a phenomenal legacy - Louis Kahn, Venturi Scott Brown, Le Ricolais and others. Kahn and Le Ricolais taught a visionary masterclass at UPenn together with the title: Beyond the Cube: The Architecture of Space Frames and Polyhedra (edited by Jean-François Gabriel). Le Ricolais' vision is still crucial for UPenn, as he was far ahead of his time, he taught generations of students that "to discover the nature of things, the secret is to be curious," drawing on mathematics and physics, engineering and zoology in search of new visions for structures of the future, visions not limited to the individual structures to be built on or above or below the earth, but to the ways they might change the nature of cities and the circulation of human beings in them.

This forms the basis of our future-forward structural classes at UPenn based on complex geometry, and, I like to think, it is part of what drives us to keep pushing boundaries into unknown territories far beyond the great legacies UPenn has.

How would you like the school to have changed during your tenure?

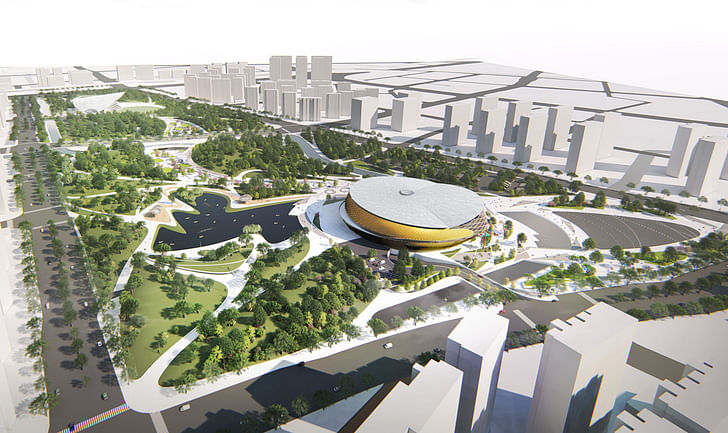

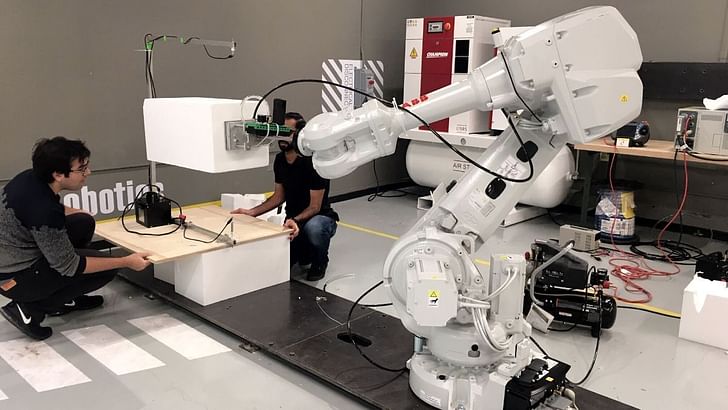

I became the Chair at UPenn after running for 10 years its post-graduate program. At that point, UPenn had had six years of interim Chairs, and the Department’s search committee was fully aware that not only the architectural practice had drastically changed, but also that education had to catch up and get in front of that. So they were really looking for a practitioner who would lead the department for the coming years. That meant that when I started as Chair, there were a lot of revisions needed both in building the standing faculty and in updating the curriculum. Together with my faculty we revisited not only courses in history, theory, technology, professional practice and visual studies, but we also set a 5-year plan in motion for larger ideas such as new Master of Science in Design (MSD) programs, 3D printing, and a large robotic lab. For the curriculum, I realized that updating the courses would be a good start – and also that these updates would need to be constant, and so I appointed coordinators responsible for each series of courses. Just recently reappointed and in my seventh year as Chair, I hope that I set something in motion at Penn that will inspire students and faculty to keep evolving the exciting things we initiated. We now have 3 MSD programs: MSDs in advanced architectural design (AAD), in environmental building design (EBD), and in robotic and autonomous systems design (RAS). We also created the advanced research and innovation lab (ARI) in charge of the large robotic lab and research groups, of which I am the Director.

Can you describe the pedagogical approach to MSD-RAS program with relation to the other focuses in the architecture department? What are some of the potential applications of this education?

The new MSD-RAS degree, a 1-year post-graduate course, will advance the reputation and impact of the School of Design by demonstrating our commitment to engaging with the present global development of autonomous technologies and advanced forms of robotic manufacturing that are transforming the practice and education of architecture, and its capacity to address the design, production, and use of the built environment. The MSD-RAS program will enable our graduates to operate at the forefront of industry research and development, to gain state of the art design and robotics qualifications, and to graduate as highly-skilled professionals, capable of impacting the present and future trajectory of architectural design and research through novel forms of practice and entrepreneurship. The MSD-RAS program aims to develop a synthesis between design and technical achievements through project-based work that requires continual experimentation with material and robotic prototyping. As such, the program has been structured around a series of projects and workshops.

The challenge to architects is to operate at scales greater and smaller than that of the building, requiring the understanding of the chemistry of materials as well as consideration of the impact of whole populations of buildings on their local, regional, and global ecosystems.

Increasingly, practitioners are finding that aside from conventional drawing sets, other types of deliverables, like lines of code and other forms of digital instruction/information for robots and other fabrication tools, are becoming a larger part of architectural practice. Has this trend been reflected or absorbed by the conventional architecture curriculum that you oversee?

“Conventional.” That is a harsh term, for something I think is already pretty advanced. In our last accreditation review four years ago, the committee stated that, after a thorough review, they found our department of architecture to be one of the best examples of the architecture school of the future. That makes me think that we left the term “conventional” behind us a while ago!

In this post-digital, post-human anthropocene phase we occupy, we choose to dive deep. I believe not only in shifting education towards the future, but also revisiting and hopefully expanding the role of the architect in practice.

These were underlying thoughts on how we re-developed our curriculum, to focus on the next 25 years; and we aim to integrate technology, theory, deep knowledge and design in one more intelligent whole.

How do the Center for Environmental Building & Design and the associated curriculum of the MSD-EBD degree program view the relationship between building design, building component specification, and issues like longevity, maintenance, and historic preservation?

The MSD-EBD you mention above deals with the renewed urgency of environmental issues – from global climate change to resource shortages and "net-zero" design – as architects are faced with demands for new kinds of services that require a new kind of professional. LEED accreditation is only a start, helping designers utilize existing technologies, but a wider range of skills is required to achieve real innovation and to meet the needs of clients in this rapidly changing field. New building design, renovation of existing buildings, and environmental analysis at many scales are critical aspects of comprehensive environmental design. The challenge to architects is to operate at scales greater and smaller than that of the building, requiring the understanding of the chemistry of materials as well as consideration of the impact of whole populations of buildings on their local, regional, and global ecosystems.

Historic preservation issues are more the study and task of our colleagues at the Historic Preservation Program, but we do have many dual degree students that take both Architecture and Historic Preservation, and do study the relationship between building design, building components, and issues like longevity, maintenance, and historic preservation.

U Penn is scheduled to exhibit work at the Architecture Biennale in Venice this year, can you share the nature of the work that’s being presented?

We are all hovering in a long delay regarding any cultural event at the moment, but to explain briefly, over the last years we developed strong collaborations with an international group of experts that support our advanced design studios. This ranges from material manufacturer’s R&D labs, to governments, and developers. The students hence get to work with expert input on their design-research work, they get to visit the city, factory, etc. and are often also financially supported in travel and publications related to the subject by these collaborators. It is a great way into graduation and eventually practice. In Venice this year we will present multiple projects, including collaborations with LeMond on carbon fiber structures, under the leadership of faculty member Ezio Blasetti, and a study on urban interventions with the GAD Foundation in Istanbul, under the leadership of Practice Professor Ferda Kotalan.

Antonio is a Los Angeles-based writer, designer, and preservationist. He completed the M.Arch I and Master of Preservation Studies programs at Tulane University in 2014, and earned a Bachelor of Arts in Architecture from Washington University in St. Louis in 2010. Antonio has written extensively ...

1 Comment

But do they teach architecture?

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.