Adib Cúre and Carie Penabad are two Miami-based architects who work nimbly across project types and between practice and academia. Their firm, Cúre & Penabad Architecture and Urban Design, is responsible for a collection of sensitive and pragmatic projects that are infused with color, rich materiality, and elemental forms, aspects that are driven by the architects' close relationships with builders and clients.

Both are active in academia at the University of Miami School of Architecture and use their teaching as a foil and fuel for their built work, and vice versa. For the latest Studio Snapshot, Archinect connected with Cúre and Penabad to discuss the firm's triumph over the Great Recession, the legacy firms they look up to, and how their 10-person team works successfully between projects in Miami and Latin and South America.

Where and when did your studio start?

Penabad: We founded our studio in 2001, when we moved back to Miami after working in Boston and going to graduate school at Harvard University. The move to Miami came for two reasons: first we were interested in establishing our own practice; and second, we wanted to pursue a career in academia. At the time, both Adib and I were offered positions at the University of Miami School of Architecture. Moving to Miami allowed us to establish a practice alongside having a full-time academic engagement. Currently, we are both faculty at the School; and I am the Director of the Undergraduate program and Associate Dean.

Cúre: We saw the move to Miami as a way for us to connect, architecturally speaking, not just to Miami but also to Latin America and the Caribbean. Both Carie and I have our roots in the Latin world. Miami’s geographic position makes it easy to connect to Latin America, both physically and culturally.

Miami is a young, vibrant city; and it is an exciting place to start a firm. Early on, we were given certain opportunities to design architectural projects in the public realm that I believe would have been more challenging to develop in more established cities.

Can you talk about your work in Miami and regionally?

Penabad: Miami is a young, vibrant city; and it is an exciting place to start a firm. Early on, we were given certain opportunities to design architectural projects in the public realm that I believe would have been more challenging to develop in more established cities.

To go back to the question of connecting to Latin America, Miami is an interesting place because when viewed from the northeast, it is considered a“ province,” but from the point of view of Latin America, it is “the capital.” So, Miami is either at the edge or at the center, depending on your frame of reference, and this makes living and practicing in the city very stimulating. It is also a port city, so there is a confluence of different cultures and different ways of thinking that come together to shape this city.

In hindsight, the 2008 economic downturn was the impetus for us to search beyond Miami’s boundaries and the definition of our existing practice and move into new territories (both literally and figuratively).

At the time, we had a number of large projects on the boards that were stopped indefinitely. As such, we had two choices: we could see this turn of events as a negative or try to see the downturn as a potential positive. We chose the second and decided to pursue a number of things that we had not done before. We looked for other markets, specifically in Latin America and did a lot of traveling, visiting numerous cities and reaching out to potential clients etc. After a while, we started to get invited to participate in a number of design workshops; and as a result of these initiatives, we received an initial commission to design an apartment in Guatemala city for two extraordinary clients. This project led us to the next job, and the next, and the next... Just this past year, we opened a physical office in Guatemala City.

Cúre: Living in Miami and working in Latin America is quite easy. For example, it is faster to travel to Barranquilla, Colombia (where I’m from) from Miami than it is to travel to Boston. It’s a two hour flight to Barranquilla, typically no delays, and pretty straight forward. There's a certain ease that living in Miami allows us to have.

In the decade since the recession, how has that pivot worked out for you and your practice?

Penabad: I would say it has been transformational for several reasons. In my opinion, during times of recession, you have to get more innovative, more creative, and more focused. Otherwise, it can be very scary. You have to turn the situation around and figure out what needs to happen so that you can keep doing what you love to do. This takes a positive mindset, hard work, and perhaps a little bit of luck. In our case, this was certainly the case. We dedicated ourselves 100 percent to our new work and in turn were able to meet some extraordinary individuals that took a chance on working with young architects on larger-scale commissions. The MAG project, which is a corporate headquarters for a sugar mill in Escuintla, Guatemala, was a good example of this. It was a dream project, that came by way of establishing a deep connection to a particular place.

I believe we were provided with the opportunity to do larger-scale work more quickly in Latin America. We discovered a slightly more open landscape where you did not need to have 20 buildings in your portfolio (of a particular size, scope or type) before someone gave you an opportunity to develop work of a certain scale (anything beyond small-scale residential I mean….).

I believe we were provided with the opportunity to do larger-scale work more quickly in Latin America. [...] you did not need to have 20 buildings in your portfolio (of a particular size, scope or type) before someone gave you an opportunity to develop work of a certain scale

We found this reality to be extremely exciting and wonder if we would have been given the same opportunities if we had stayed working only in Miami.

Cúre: Working in Latin America, and designing using the rules of construction in Latin America, requires you to be inventive in terms of how you build, especially when you consider cost and the often restrictive palette of materials that you have to work with. In the case of the MAG headquarters, the building is located in a very rural area along the Pacific coastline of Guatemala. This relatively isolated context required us to be extra conscientious in siting, material selection and assemblies. The context demanded restraint and resilience in terms of the way that we expressed ourselves architecturally.

Additionally, It seems the work you do in Guatemala is more tied to the local climate of that place.

Penabad: Absolutely. We are committed to creating an architecture of place; and we have always been interested in the lessons of the vernacular because we believe there is great wisdom in vernacular constructions. So we look closely at regional traditions when we are working. In the contexts that we have been working as of late, we rely on low tech, time-tested principles of architecture and urban design to ensure the development of projects that can withstand the test of time.

We have worked with some amazing consultants. Arup, for example, served as consultants for the MAG headquarters project. While they are known for their technological innovations, they reiterated the importance of the basics such as siting and cross ventilation. Practical experiences like this keep us grounded and focused on the fundamentals.

Cúre: To point to another example, in the case of the Escuelita Buganvilia, we were committed to preserving the existing landscape as much as possible. We carefully sited the project to protect the existing trees, not only because they were beautiful but because they provided another layer of shading that was absolutely necessary for the children to attend classes and inhabit the building in a more delightful way.

How do those sensibilities extend to the construction aspects of the project?

Penabad: We participate in construction administration from beginning to end. This process tends to be more fluid in Latin America than in the US. Changes can arise at the site when issues are discovered with less bureaucracy than in the states (at least this has been our experience). But also, the forms that we are exploring are quite fundamental and rely on a certain degree of repetition. Repetition is built-in to develop a certain expertise by those who are constructing the building. Moreover, the repetitive modules allow for a certain economy of means that then permits us to redistribute the efforts in other directions, especially in terms of detailing.

Our material choices are robust— concrete, plaster, stucco, metal roofing, stone or brick. We try in all cases to remove as much drywall as we possibly can, as well as any unnecessary glazing whenever possible. When we rely on finer carpentry details, it is usually because we have discovered that the builders have a tradition of carpentry that we can capitalize on. Being on the ground with our team allows us to discover what the true possibilities can be.

Cúre: We’ve also been able to find local laborers that are good at certain crafts such as plasterers or metal workers. When products are spec'd from abroad and brought in from around the world, these kinds of laborers are less in the forefront, but we search them out and try to collaborate with them as much as we can. This not only supports the local economy but keeps these traditions alive for future generations.

We’ve been able to find some of the more specialized laborers in Miami, as well. Early on in the Design District, when we were just starting out, we did a project called Oak Plaza. The building was clad in local limestone, and we found people who had been working with limestone in Miami for generations. To our surprise, they were willing to do this small project with young architects who were there every morning to make sure it came out right.

Some of your projects in Miami fall more in the realm of landscape or plaza design. Can you share some thoughts on those projects?

Sela Square, a proposed dog park in Little River and Oak Plaza in the Design District, displays our interest and commitment to the development of public space in Miami. We are in a subtropical climate, where we can live indoors and outdoors nearly year-round. Because of this, the life of the city extends itself to the outdoors, maximizing our capacity to gather and enjoy the built environment.

Miami is still a young city and unlike other cities, it has yet to truly invest in a robust public realm. We think this is an important consideration as the city grows and matures. Interestingly, Oak Plaza, which was the first plaza in the district, was developed on private property by DACRA developer Craig Robbins. This is a Miami phenomenon.

In the case of Sela Square, designed with MVW Partners, we conceived of a space that could be utilized year-round to accommodate a number of activities. These included: a central dog park; pop-up exhibitions; outdoor theater; cafe etc. We worked hard to create a space that could draw people of different ages and for different reasons and believe that projects like this are critical in the shaping of new districts and neighborhoods in the city.

How many people work at the company?

Penabad: We are currently 10 permanent employees between both offices, with a number of interns that fluctuate in and out.

Are those interns drawn from the University of Miami, typically?

Cúre: For the most part, yes. They come from our experiences working with students at the University of Miami. In the case of the Guatemala office, they are all locally trained designers.

What are other offices that you look at for guidance and why?

Penabad: It is difficult for us to point to a single office or individual, because there are so many that have influenced how we see and practice architecture. But if we had to name a few that we have studied for guidance they would include: Gunnar Asplund, Aldo Rossi, Louis Kahn, Sigurd Lewerentz, Gio Ponti, Kazuo Shinohara, Lina Bo Bardi, and Venturi Scott Brown. Now that we have been in practice for more than a decade, we look at these figures in different ways, trying to understand how they structured their practices and built a complete body of work.

Cúre: You will notice that most of these architects are no longer with us. This is important to note as we believe that it is necessary to study the life and arc of an architect’s work from beginning to end. This includes the master works alongside the unknown and sometimes less-accomplished projects.

Is there a certain practice model that you employ for your practice?

Penabad: In our case, we have a studio-based culture. We are interested in engaging the people that we work with intellectually; and we want to empower them to take ownership of the work. We strive for excellence by creating a productive and inclusive atmosphere that results in long-term relationships with our clients and our employees.

We are grateful to have had the opportunity to teach and practice. In many ways, academia has allowed us to intellectually engage with ideas that might not have been possible within the world of practice; and our experiences in practice have sharpened our contributions in the classroom.

Can you talk about the relationship between your work in practice and in academia?

Cúre: We are grateful to have had the opportunity to teach and practice. In many ways, academia has allowed us to intellectually engage with ideas that might not have been possible within the world of practice; and our experiences in practice have sharpened our contributions in the classroom.

Teaching has also allowed us to travel with students quite a bit. We have been teaching a workshop for 18 years, where we travel to a different city every summer. It has allowed us to visit and study cities from across the world. In the last decade, we have been focusing on Asian cities including Mumbai, Shanghai, Tokyo etc.. Our first visit to Tokyo was in 2002; and in many ways, it challenged our western-focused ideas of architecture and the making of cities. These lessons expanded our teachings at UM and were incorporated into our design projects in practice.

Penabad: We set out to pursue this double life (so to speak) inspired by our mentors. All our experiences in practice were through our teachers, both at the University of Miami and at Harvard. We saw this as a model that was not only fruitful, but also inspiring.

You sure do have a lot of built work for people who are so involved in the academic world.

Penabad: I think this says something about the University of Miami School of Architecture. We are located within a metropolis; and the school supports professors who are also practitioners. The school makes the argument that architects who are academics should be judged by their creative practices as well as by their teaching. So, the school has nurtured these two passions.

What is your firm’s approach to work-life balance? Do you offer flexible / remote work schedules?

Penabad: I think the architecture profession needs to move into the 21st-century here. We do offer flexible work schedules. We live in a world where we can always be digitally connected and we do not have to be in the same place to be productive. We have an office in Miami and an office in Guatemala, and in our office in Guatemala we have someone who works remotely. It has been working well. The key is to hire the right individuals who are both rigorous and self-motivated.

Speaking as the principal of a minority- and women-owned practice, I think that more flexible work schedules are a way to continue to support women in the profession through transitions like childbirth etc. We are such a creative profession that there is no reason why we can't apply that level of innovation to the way that we think about the work day or the work week. We try to hire the best people we can and then we empower them. We do not believe in micromanaging; we believe in establishing shared values and creating clear goals. The objectives can be met while sitting at a desktop in the office or by working remotely for x-y-z reasons. In the end, everyone is accountable for their work.

How do you look for talent for your office?

Cúre: We typically hire from our network of students at the University of Miami (both current and alumni). We also receive inquiries from abroad and from other schools of architecture. In the Guatemala office, everyone is a local architect, trained in Guatemala, with different levels of expertise. They exhibit great technical abilities in terms of construction knowledge and this has been very helpful in terms of overseeing the work.

Penabad: I would agree. The majority of our employees have come to the office through direct personal contact, oftentimes first at the university where those connections are more organic, and then second through referrals, inquiries and applications.

Where do you see your office in five years and in ten years?

Penabad: We are committed to continuing to develop an eclectic portfolio of projects that ranges from small-scale furniture designs to masterplans. We want to sustainably grow the firm and continue to do work that we believe contributes to the building of better cities with clients that challenge and motivate us to solve critical problems.

We are interested in continuing to develop new housing models for a variety of contexts, as we believe this will be one of the greatest demands and challenges of building the contemporary city. We are particularly interested in developing these models within existing urban neighborhoods in Guatemala, Colombia and Miami to promote denser and more compact urban communities. We believe that the compact city, connected to ample amenities and urban transportation, is the key to a more sustainable and resilient future.

In Latin America, housing is in such high demand, particularly affordable housing within city centers. As stated earlier, we see housing as an integral component in developing more resilient and equitable cities.

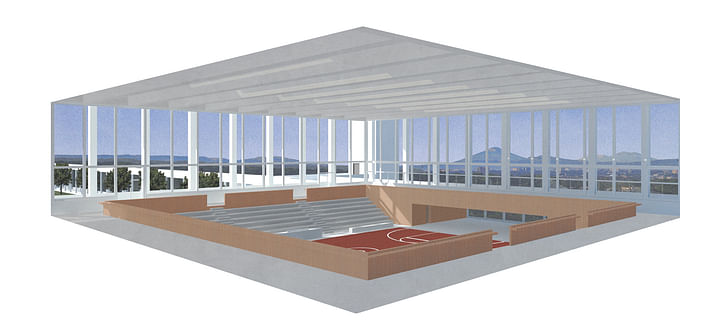

Beyond housing in the city, we would welcome the ability to expand into new territories, including the design of institutional buildings.

Why do you see housing playing such a prominent role in the future of your business?

Cúre: In Latin America, housing is in such high demand, particularly affordable housing within city centers. As stated earlier, we see housing as an integral component in developing more resilient and equitable cities. And it is not just about doing new buildings from scratch, but engaging in meaningful adaptive-reuse projects. Several years ago, we designed a master plan for Barranquilla’s city center, a sector full of beautiful Art Deco buildings from the 1930s that are in a state of decay. But they can be recovered. The answer is not to demolish these rich urban fabrics but to work within them to restore and augment their ability to shape a new city. We welcome this challenge.

Antonio is a Los Angeles-based writer, designer, and preservationist. He completed the M.Arch I and Master of Preservation Studies programs at Tulane University in 2014, and earned a Bachelor of Arts in Architecture from Washington University in St. Louis in 2010. Antonio has written extensively ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.