Born in El Salvador, Mia Lehrer grew up under a mother and father committed to making a difference in their local community, a quality the pair passed along to their children. It was at a young age that Mia and her siblings began advocating for the well being and empowerment of those around them through pursuits like teaching locals to read at their self-led summer school in the family’s home garage. Later, the family left Central America due to the break out of civil war and young Mia began to develop an inclination towards design. She explored vocations in architecture and landscape design and soon enrolled at Tufts University, pursuing a degree in Environmental Design.

With a growing and solidified interest to work on the design of cities, Mia embarked on a self-directed education through reading and attending lectures, leading her to the Master of Landscape Architecture program at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. In 1982, Mia Lehrer + Associates was founded, and the once curious youngster had become an educated practitioner. Fast forward to today, and the practice (now Studio-MLA) has grown from a modest team of 3 to a robust enterprise of over 40 professionals committed to design excellence in landscape architecture, urbanism, and planning.

Archinect’s Paul Petrunia sat down with Mia Lehrer to discuss her rise to prominence, the challenges of being a woman in architecture, and the critical lessons she’s learned during her nearly 4-decade-long career. And make sure to check out the accompany Studio Visit article to this interview, which takes a look at Mia's Los Angeles studio itself.

From what I’ve read, your parents were activists involved in a lot of good socially progressive initiatives. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Yes. I grew up in El Salvador, surrounded by volcanoes, tropical forests, lakes and beaches. It was like paradise. Not least of which were the orchids and the birds, especially hummingbirds and parakeets. My parents had emigrated from South America and Europe, and were just in awe of this sort of paradise. They became extremely engaged in the protection of natural resources. My father became very involved and helped found an organization that still protects natural resources. He was very saddened by the level of poverty, so he helped found a small community development bank that helped people buy materials and pay them back over time. One room at a time, was the story.

I grew up in El Salvador, surrounded by volcanoes, tropical forests, lakes and beaches. It was like paradise.

While he was helping build houses, my mother was doing microloans–she just got a group of women to give microloans to small little businesses on the street. Nowadays, we are all very much in tune with environmental justice and economic justice issues. They just came up with these ideas out of a sense of urgency, given that they lived well in that they were doing well, that they had to give back and that they wanted to build community. When the Peace Corps arrived in El Salvador, Sargent Shriver stayed for some months in the house next door to ours. But when the Peace Corps volunteers started getting rides instead of going with their backpacks on the streets, my mom would always pick them up. You know, "come have a good meal," she’d say.

Did they immigrate to El Salvador from Europe at a later stage in life?

No, no, they were very young. My father was 17. He never finished high school. He immigrated as a result of a very bad time in Europe. Not necessarily because of Nazi Europe as it matured, but because there was economic and social unrest. Of course, ten years later, it became what it became. So he took his parents out of Europe. He went back and sort of ended up meeting them in Paris and then took the family out. But my mother's family had all gone to Brazil.

They were very active. There was always something going on. Eventually, my father helped fund summer camps for those urban children to go to the mountains. Many of those kids, if they went to school, didn't have any kind of opportunity to have vacations or family time.

There was always something going on. Eventually, my father helped fund summer camps for those urban children to go to the mountains.

They were very involved in the community, and I think it had a very big impact on us. People didn't know that you had to be light on the land. But that's just the way things were. You used things two or three times. There were five children. And he used to insist that we take baths in the same water until the water was dirty, really dirty. Just because, "why would you use more water?"

This wasn't a financial necessity?

No, it wasn't financial. There wasn't a scarcity. It was just that it made sense to be light on the land, you know, to just be different and to be respectful. And so obviously, they instilled in us a sense of responsibility towards the world around us and towards our brethren. At one point, there were some young girls from a favela, if you would call it that, near our house. And my father realized that they didn't know how to read or write. And he said, "well, you're going to help the girls." He got us a table, a long table and benches and took his cars out of the garage and we had a school.

And so for that summer, and three or four summers following that, we were teaching this group of young women how to read and write. Of course, when you're 10, 13, and 14. You know, with my siblings, we thought that was awesome. We were playing teacher, right? We didn't feel the heft of the enterprise. But it was really wonderful. So it was an amazing upbringing. Eventually, I found it funny because we went into...with my oldest children, we arrived at the school district when they were starting to talk about recycling.

And of course, in what was then the "third world." In the third world do you recycle? Basically, you kept your paper separate from your metal and the metal was recycled by somebody and it was always reused. But in the school district, the sanitation department and the city were saying we need to recycle. And they made the right choice to encourage the recycling education to happen through the schools. And so adults learn through the children. And I always found it very lovely to see it all come full circle. Eventually, I also got really involved in the schools. That's how I got involved in community work, planting trees, because the schools had already all been asphalted to death. And we had a wonderful principal at our school. For her, it was about the esprit de corps, but also about the school looking nicer. She was a very proper and very elegant lady and an amazing leader. She just wanted it to look nicer. So we started pulling out asphalt and planting trees and realizing the power of doing things together. It was quite wonderful.

What about your appreciation or awareness of landscape? Do you feel that that was your first hands-on experience working with the land?

No. We used to garden a lot in El Salvador with my mother and we were very conscious about flora and fauna. My father had a construction company that sold construction materials and he was involved in several businesses. So for three or four summers during my high school years, I basically worked in different kinds of offices and I had expressed an interest in design.

I worked for an architect for a summer and I had to design parking lots and I did not enjoy that at all. The next summer, I worked at my father's store, selling material. In the third summer, there were some World Bank people in El Salvador doing a planning study for the coastal area of El Salvador, which had been ravaged by DDT. The fisheries were gone, everything was gone. And these guys had come down to figure out if they could fix things and if they could bring tourism. And to bring tourism, they would have had to restore some of the beaches and some of the inland areas to make it more appealing because they had been growing a lot of cotton and had lost a lot of the native vegetation. So I worked there for three months and then another six months. I started learning about mapping which I really ended up loving.

Eventually, it became very political. I realized looking back that what I learned early on has come to be. But they were supposed to choose around seven, plus or minus, site areas of hundreds of acres each to do trial restorations and to promote tourism in those areas. And the Japanese government had put money in. The Japanese government was very strong in Latin America. They were making textiles and paint and other things. They were manufacturing and had good businesses in Latin America. And so they were paying for this study. But it was through the World Bank.

So I realized planners existed, that planning existed. And I soon went to college.

And so when one of the generals, a very strong military man, did not get his property identified as a development opportunity, he basically canceled everybody's visas. Not mine, of course, but these American and Japanese advisers. And they had to leave in two months, pick up and go. And that was that. I probably have one of the only copies of that document and it's beautiful. So I realized planners existed, that planning existed. And I soon went to college. I went to Tufts and they had an environmental design degree, which was more like an art degree.

Was going to the U.S. the plan?

No, going to the U.S. became the plan when the civil war broke out. My parents were very liberal. Us kids were very liberal and artsy. And, you know, our friends were starting to join the underground and things were getting hairy. And my father was scared. I was really scared. And so we also went to Tufts for four years. I started understanding environmental planning a little more and I was toying with the idea of going into international relations. I think at some point I realized I really wanted to work with cities and with design. And I started reading certain books like Bacon's Design of Cities and others.

Eventually, one of my favorite professors from Tufts and professors from Harvard and M.I.T. had formed a group that wanted to see where to take environmental design. This is the '70s. They're wanting to see how you make sure cities are planned for with care and that cities in other parts of the world are starting well. Globalization is starting and other continents are starting to see how America's growing. They wanted to export good ideas, not bad ideas. So they started a master's program.

I didn't know that this profession existed. And the next thing that happened, I was smitten.

I joined that program and you could take courses and lectures. Kevin Lynch was giving a lecture series course. And the lectures were at Harvard, at the Graduate School of Design. So I started going to that and I saw a show of Olmsted's work for Central Park. And the drawings just drew me in. I didn't know that this profession existed. And the next thing that happened, I was smitten. And then I met Peter Walker. I went up and I said, what is this? Can you explain this to me? And then he explained it. And the next thing I know, I'm applying, I'm putting together a portfolio and then I end up at the Graduate School of Design and at the time that I was there, Jack Dangermond. Do you know who he is? Do you know what GIS is?

Yes.

Do you know what Esri is? In Redlands. The company that created GIS?

I’m not too familiar.

OK. Well, they created the mapping system that makes...when you pull up a map and you do your Google and all of that stuff. It originated from the work that they did. And there was a little lab at that school of design and he was working there and he was 10 years older than me. And a number of us were guinea pigs. And, you know, where you were doing things for this wonderful older, I think he was getting a Ph.D. at the time. Eventually, he came back. So he's in Redlands and he does amazing things all over the world. And, you know, understands regional planning and infrastructure planning...

So that work was the basis behind all of the navigation systems that we use today?

Totally.

That’s incredible.

Yeah. So I'm really proud to say that it came from there. Because there were these guys thinking big picture. You know, I went into it thinking about how I can design a park. And when I was in school, they were people who were designing fun beautiful parks. And Peter Walker, for example, was there at the same time as Frank Gehry. They were all into art, like how art influenced design. But the other guys that we had to take courses from were into a whole different thing. Like, how do you understand the world? How do you impact it the least? How do you do good planning?

I worked for a firm for three or four years and immediately created my own office because I had children...

And so it was a heady time to be there. Of course, it took my mind off of everything else that was going on. And it was pretty awesome. It took me a good decade or two once I started working to figure out how the larger picture was something I could work with. I mean, I didn't go into a career path where I'm working with a firm and doing projects, you know, I worked for a firm for three or four years and immediately created my own office because I had children and you couldn't...it was really hard to be in an office with children...

And so that was three or four years after graduating from the GSD?

I worked for three or four years. And then I did my own thing.

Was that in Massachusetts or was that here in LA?

No. We moved. So I met Michael Lehrer at Harvard at the Graduate School of Design. And we were going to go work in New York. But there was a downturn in the economy. And, you know, he was gonna go work for IM Pei and we weren't going to even be able to pay rent, never mind anything else. So, we came to California and we ended up in Laguna Beach. He was working for IBI Group and I was working for POD, which is a company that doesn't exist anymore, but it was absorbed by Sasaki. And then four years into it I had two little kids and I just started doing my own thing.

So what did your practice look like in the beginning? Was it called Mia Lehrer and Associates?

Yeah, it was landscape design and I stayed very good friends with Peter Walker and Martha Schwartz, my classmate. And Pete used to do work with Ricardo Legorreta. Initially, Ricardo's working in the U.S. was a lot of houses. But I mean, when I'm talking about houses...like houses, you know, it's like an institution. And so it was too hard for him to manage a project of that scale. So from wherever he was, I think at the time he was on the East Coast, he handed me over these relationships and I started working with Ricardo and I did projects and then there were also other referrals with other movie producers, actors, actresses. It was everything from Sally Field, Jamie Lee Curtis, Robertson Marcus, Joel Silver, Dustin Hoffman, Sally Kellerman. And I would have like three, four or five of those at a time. And it was pretty intense.

I was like, okay. And what was wonderful about it, of course, was they knew how to dream. They knew how to make a scenography, you know, there were no hurdles in their mind. Like, yeah, well, why couldn't it be 10 feet higher? Well, because it will require 100 trucks. That's OK. Right? A hundred trucks of dirt. So it could be a hundred... You know, it was like all these kinds of things that happened...like with trees: "I'm building a new house, but I don't want to kill the trees." Well, we're going to have to move them. "Well, figure out how to move them." And then, you know, I'd meet companies like... well now it's Brightview. And they said, you know, let's try it. We did it a few times. Let's try it. I think it'll be fine. And you'd be moving thirty 50-foot palm trees around.

It was everything from Sally Field, Jamie Lee Curtis, Robertson Marcus, Joel Silver, Dustin Hoffman, Sally Kellerman. And I would have like three, four or five of those at a time. And it was pretty intense.

It was funny because one of the clients was Arthur Greenberg, a very well-known attorney, and a nice, nice man. And at the time, a lot of these people very interested in art started thinking of architecture as art and started essentially collecting buildings. So I had been hired to do that house with Ricardo and this tree is dangling over the house. And I said, oh, my God, I hope the guy was putting it in the right place. And he said, don't worry about it. You have insurance. Just to joke with me. But it was real, something could have happened. But the guys all knew what they were doing. People were building big buildings. So people knew that it wasn't such a big mystery. But it was fun because people understood beauty and understood modernity. And it was an exotic set of experiences that I had with many of them.

So was it a struggle in those early years.

No, there wasn't really a struggle. Well, I was working out of our house and I always had help, like one or two designers working with me. So, you always had to have enough to keep you busy and two other people busy. I couldn't get work if I didn't have somebody producing back at the office. So I quickly learned that I couldn't do it all by myself. I mean, I don't know, now, with digital design or with computing how it would have been different? But at the time, somebody had to be producing and you had to be managing construction jobs or getting new projects. So it wasn't a real struggle, but I also wasn't paying rent. And, things were evolving.

What year did the practice start?

1982

So now you have this huge space, 40 people on staff, I believe. How did you scale up? Was it a slow process? Were there any big projects that helped you take a few bigger jumps?

Yeah. Early on, when I started, I continued doing houses and I still to this day have an obsession with doing a garden or two at a time. It nourishes me. But, when there was a project for Barnsdall Park Restoration or for Union Station, I would be asked like, how many stations have you done or how many parks? It's only like five acres, you know, compared to the estates I was doing and the actual budgets were the same. But as a woman, I think I would get asked, 'how many have you done?' in the interview. But I got a few of those projects and I started doing schools and I started getting involved with the LA River efforts through the poet Lewis McAdams. I became his friend.

He taught me about being, you know, sort of bullish and passionate and the power of words. And I taught him about design. You can have all these ideas, but at some point, you have to solve physical problems. People can't just be looking at the river. They have to get down there. At some point, there's going to have to be stairs. So it was a very interesting time for all of us just trying to figure out on some of these projects how to make a difference.

Did you consider him a collaborator or was it just a friendship?

I consider him a collaborator, maybe a comrade in arms. We became passionate advocates. The advocacy that he did was extremely useful because he could go into City Council and just say, we got to do this. I would also follow in his heels, and not just me, there were others who were supporting him about what it was he needed to do to help visualize the change. In a sense, he thought it was more environmentally healthy than it really was. And we all started discovering that there needed to be a lot of change. So all that was volunteer work. For the schools, I would get a job here and there for a school. And I thought, wow I'm doing a school!

Then I did planting with a couple of the nonprofits like Tree People, of certain streets, like in my neighborhood: Vermont, Hillhurst, and Talmadge, where you have to go in and ask your neighbors, do you want to plant a tree? Will you take care of it? So we did a lot of that work. And I met Andy Lucas as a result of that work. And eventually, I was on his board and I started getting more engaged with the Environmental Green Coalition in Los Angeles. At that point, I felt that I really needed a balance between the kind of work I was doing in residential and the other work that I was doing. And what I came to realize was that occasionally, I would get calls from some people who were incredibly entitled. You know, there'd be an 11:00 pm call about some tree that had bugs or something. So one of the things I realized was that a lot of people were starting to be involved in environmental causes from the movie industry. There always was an interest.

One of the projects I worked on that I loved was the Painted Turtle Camp that Paul Newman, seeded in the East Coast and then did one out here with Lou Adler and his wife. And some of my clients who weren't in the movie industry, who were venture capitalists who got very involved and very passionate about the work with camps for children with cancer and other diseases. And it was a beautiful sight. It was like a big garden. And that's how I started scaling up. You know, the schools, some parks, and those kinds of projects, and then I started really getting involved in the environmental movement with Andy Lipkis and others and then moved onto bigger projects.

So I spent quality time in the house, the third floor of my house in my studio. I probably moved out in 1992-93 when my youngest was three or four and went into the fine arts building and started doing some civic work and also some university work.

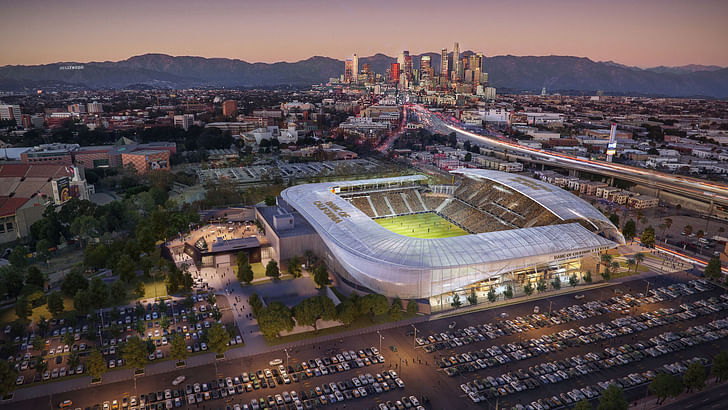

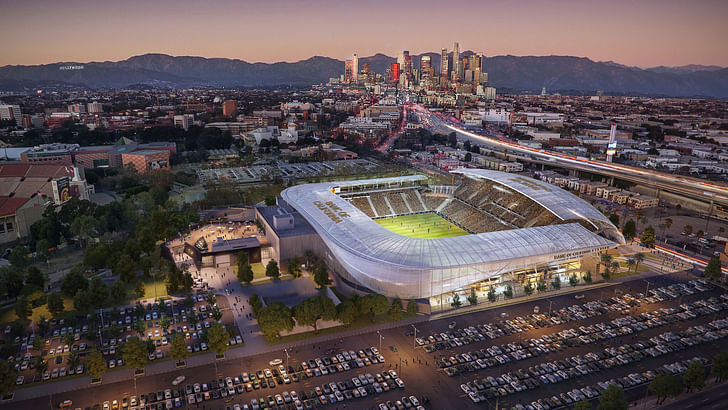

One of the first projects was down in Playa Vista, taking a look at the potential of turning some of that site into a wetland and looking at Ballona Creek. I would get small budgets for design and strategy. My contribution was understanding urban design and urban planning, but also visualizing the potential change, the environmental change. So, I went from two people to then in '92, I probably had seven people and then in 2007, I got to work on the LA River Master Plan and on Compton Creek and on Ballona Creek. Then I did a master plan for the Baldwin Hills oil fields and all of that sort of then led to bigger projects. So I went from the seven people to maybe 20 and then eventually the thing that changed my horizon was all these stadiums. In my life, would I have thought I'd be doing a baseball stadium first?

Dodger Stadium?

Dodger Stadium, then a soccer stadium, and then a football stadium.

And those were all relatively recently?

The football stadium we started 12 years ago on Hollywood Park, just the re-imagining of Hollywood Park, and at that point we were 20 people. But then that project went from just specific planning to something more big picture. At that point, I'd already worked on Playa Vista as a planning effort. So I went from Playa Vista to that. So, how I pitched myself for Playa Vista was, because I had never done a master plan of 400 acres by myself, I studied some people whose work I admired and at the presentation, I presented an analysis of the work that the people that I admired had done. This is why I think this was a really good project. The way they approached A, B and C. And it turns out by luck, the project manager had worked on one of those projects. This was before Google, so I didn't know!

So you didn't even realize you were kissing his ass?

No, I didn't realize I was kissing ass, no. So it was pretty fun. But every one of these projects was a big feat. And then eventually we did a masterplan for Silver Lake.

The reservoir?

The reservoir. We did some work in San Pedro with an urban design firm. And the portfolio started getting stronger. Now here we are with 3 stadiums: Dodgers keeps on going. The other stadium is in construction. LAFC, the soccer team just finished. My team is always very critical of projects that they don't think fit our vision and our values. What became clear to me is that, for example, when it came to Hollywood Park, it was of a giant infill project. You know, it's 300 acres. Yes, there is a football stadium, but the Football Stadium has an incredibly strong cultural and community component to it. We were part of the conversation and the developer was committed and so was the mayor of Inglewood. So I couldn't be guilted into, "Oh we're just doing a stadium," because I think building 3000 homes and providing jobs and creating 30 acres of parks in a community that doesn't have very many parks was a big feat. It was exciting. I think stadiums around the country are doing that, they're really wrapping themselves into communities and integrating themselves into communities to add value. So here we are. And I have a little office in San Francisco, too.

When did that open?

About a year ago.

Why? Because of the projects that you have up there?

We have some clients there, but also because one of the principals just wanted to be in San Francisco. And we all love San Francisco. So we're hoping that it will flourish.

It's a good excuse to get up to San Francisco as often as you can. So, as such a dominant figure in the LA landscape architecture scene and as a woman, especially working on these kinds of “macho” projects, like sports stadiums, have you dealt with much sexism throughout your career?

Yes, I've dealt with a lot of sexism. But funnily enough, I think on some of the stadium projects, because it's so anomalous to have a leading design person on the team, I would say that by and large they find it curious and interesting, but it's not easy. For example, when it comes to collecting bills on any of the projects, any one of the projects they can owe. You know, people, whether it's in city projects or public projects, private projects. If you, at some point put your foot down and say, hey, you know, it's been a while. What's up? You know, the contract says this, the contract says that. If you do too much of that, you're basically an annoying bitch. And a man can just make a call. Hey, you know, we're going to stop work because you're 90, 120 days overdue.

It's complicated. But I feel that yes, and I don't feel totally at liberty to talk about it right now, but I do feel that that as a woman, you're not always taken seriously. But I always find allies. I'm going through a particularly difficult time on something right now. And I definitely think it is about being a woman. And in the sense that I'd like to fight for ideas and fight for values and for our mission and for doing right by community, It's very degrading. The most difficult thing is how difficult women are with women. Women in power can be nasty and really difficult with women.

It's understandable that it's been a much bigger struggle for you to get to where you are as a woman. What do you credit to achieving this level of success? Do you just have to kind of push through that friction that comes?

I mean, I sometimes can't believe that I can make it. First of all, I have amazing women that I work with. And I've always had a really great connection with women in a slightly younger generation than myself who are absolutely fearless and have no...you know, it takes them a while to have the experience I have and I try to protect them and I try to mostly open doors. But just seeing them succeed and flourish gives me pleasure because I'd like it to be better and easier for them. And I have a daughter about their age. And then two granddaughters and all that comes into play. But, I think that coming from a small country and being sort of culturally sophisticated and growing up in a family where there were no boundaries. First of all, my parents didn't make a difference between boy and girl. Even though neither of them had finished high school because they left Europe at a certain time, they were absolutely expecting their daughters, and there's five of us, two sons and three daughters, to actually be professionals and be a part of the world in a meaningful way. So there was that. But, you know, in a small place like that, you can get so much more done. When I was still contemplating going back to El Salvador at some point, it was in part like, I could have been Minister of Environment, like that was my next step. But I was in the U.S. by then and it just seemed like a great place to be for my future.

You just develop a very tough skin and you just keep on going and you want to do the right thing.

I'll go to meetings after I've been shat upon by someone and I'll go to a meeting just to observe what's happening in the next steps of the project or something. I think it's a personality. You just develop a very tough skin and you just keep on going and you want to do the right thing. You think you can make a difference and you just keep on going with blinders. And I'm sure that I piss a lot of people off. I know that there are other people that are incredibly thankful that they can count on me. I just had a friend passed away yesterday.

I’m sorry.

His name is Antonio Gonzalez. He was an environmental leader, a Latino environmental leader. Do you know who Willie C. Velasquez was? He was in Texas, a very strong advocate for immigrant rights. He was just this amazing force. But he got horrible cancer. When you would sit with him, he would tell you American history and talk about Jefferson and talk about Lincoln. And he had memorized speeches and he was just this awesome fountain of knowledge about America and American history. And he used to be very supportive. And two months ago, he called maybe 80 people and said, I want to see you.

And that's when we saw that he was in a really frail state. And he said, either I'm going to be OK or I have to say goodbye. And it was an incredibly meaningful meeting for me because we only supported one another in terms of environmental justice. And it's not like we ever had contracts together. We just met and had meetings as groups about what we were going to do about this proposition or what we were going to do about what's going on about any number of things. But it was more like camaraderie. So I have a lot of comrades. Sometimes I say to my daughter, I can't wait till I can spend more time with her daughter and retire. And she says, “yeah, right.” Nobody can believe that I'll ever let go. But, you just push and there are the occasional people who will give you strength: your family, your friends, your collaborators. And then you get stomped on and abused, not in the way that other people were. I mean, I've never had that level of abuse ever. But I have been stomped on and put down. Projects that should have come naturally, given my experience, didn't come so naturally, I had to fight for them.

I mean, it seems like that type of struggle can either knock a woman out or make her stronger. Do you feel like it made you a stronger person, just having to push that much harder to get your work realized?

Yeah, I think it made me stronger. I worry sometimes that maybe I'm not so likable, but it is what it is. In the end, we're part of a community in Los Angeles that’s trying to make a difference in building a better place. And that's what it takes.

Within the landscape of landscape architects in LA and in Southern California, how would you define the unique style and approach of your work?

I think people are either stylized or have an approach that's more sort of not about a process necessarily. And I think the approach that we've developed that I feel very strongly about is a process where you engage stakeholders, and it's not just community, but stakeholders could mean advocates, policymakers, elected officials who still need to understand the process. They need to understand what it takes to do something. I think we're modernists. But we're also solving problems. I would say that I get inspired, not just by the place and the community and the landscape around this genius loci. But we get inspired by people's dreams and aspirations that are engaged meaningfully in these project processes and what they want. It's a meaningful experience. I can't say that it impacts the way the line draws exactly, but it impacts what that line does, where it takes you from A to B and where, if they thought about the experiences they had with us in community conversations, how it influenced the result of the design.

So each one of our projects, when you think of the Natural History Museum and at the time that we were interviewed, it was five acres of asphalt and they have a board of directors who say we need to connect more to the living natural history and not just have things down in the basement that isn't living. So that meant a garden. But what kind of garden? We had just finished the LA River Master Plan and really had a sense of sort of the in geologic transit in a natural environment. And, at the time, we started talking about the term "urban ecology," which is not just our term as a firm, but it was a term that people started connecting with. We can't restore Los Angeles to what it was in the sixteen hundreds. We have a new reality. And what is it? And it's some kind of urban something. Creatures adapt and we can make it better for them and we can save water and we can create meaningful places. We need a future and we need sponges for water and all these things. And so let's experiment with urban ecology, and let's start really fleshing out what a new urban ecological destination would look like. And it's amazing, just by virtue of the fact that there was no hardscape. How fast trees grew and how fast habitat came. And it was how much it's loved and appreciated, even though it's not a pristine refined landscape. It's sort of an ecological experiment.

So, you know, all those sorts of things made us really curious. I'm very interested in the urban forest and how we can push for the idea of there being many more trees planted in the city and how maybe it's not every 35 feet, but there are groves that get planted as we move through cities. We've been doing a lot of thinking about that.

We always loved mapping here. We were part of an exhibit at the Getty on the future of Los Angeles and understanding its past and the potential and where the gaps are. Our things are always a little bit one-off. When the gallery Hauser & Wirth called and they wanted to do something in the middle of downtown, we decided to show...Have you been there? Have you met my chickens?

No.

You have not met my chickens? Well, Hauser & Wirth chickens. So there's two courtyards. One big courtyard in the middle. Right now, it has five Calder's that are awesome. Amazing Calder exhibit. And then there is an urban agriculture garden. I mean, it has food...sort of...because it's a little shady. But we have chickens and the chickens are awesome. And, we did a cactus garden in the front.

When you present art in galleries, when you're putting up artwork, they usually do little maquettes of all the pieces. So we presented the plants that we were going to put in based on plants we were actually buying. And now everything's grown dramatically and you realize that a small patch like that can be so important. It's called a habitat patch, but we planted a big oak tree and the oak tree arrived and birds were following it. It was amazing. Like, really crazy. I am considered a regionalist. Some of my peers will say, “Oh, Mia's just a regionalist.” First of all, I've worked in other places in the world, and I just love being very much a part of every aspect of the process. And I traveled a lot in my life between when I was, you know, 20 and 30. And I was working for Peter Walker and I was going to Europe, to Berlin to do projects. And I traveled to visit family in Brazil and Israel. I was global. And I speak many languages. But there's so much to do here.

The way I operate is by really understanding the way things work, the politics, the ambition of the leadership, the realities of budgets, the realities of community groups who are particularly interested in advancing certain ideas and issues.

The way I operate is by really understanding the way things work, the politics, the ambition of the leadership, the realities of budgets, the realities of community groups who are particularly interested in advancing certain ideas and issues. When Paula Daniels, who used to be on Heal the Bay board and other things, worked with Antonio Villaraigosa, the mayor at the time, to create a food policy council. She invited about 20 of us to be on this food policy council. And I'm thinking, oh, my God. It was basically to understand how agriculture works and what kind of food are we eating in the inner city? And how do we break down the silos and how do we try to start understanding better how we get good food to everybody? And we did a competition and we won this competition. We called it Farm on Wheels. And it was about how to distribute. I didn't grow up in the U.S. or in California. But in the 1960s, apparently, the public library used to have libraries on wheels.

And they used to go to different communities one day a week, and people who couldn't go for any reason could get a book. So we were posing a similar food thing with fresh food so people could get fresh food in different parts of the city. Of course, now Amazon does that sort of thing, but it did actually create a very interesting experience. It was very well received. And Paula has gone on to have food policy adopted in different parts of cities in the country where there are some metrics associated with fresh food, whether it's in schools, but also in farmer's markets so that you can judge whether it's really fresh or not. It’s amazing work. And there I was every Wednesday morning. It was just curiosity and friendship and camaraderie. So I'm just a regionalist, but I am in our metropolitan area of 40 million and it is pretty big. And there's a lot to do.

It's a very diverse region. So clearly from just talking to you about a lot of the endeavors you've undertaken, you obviously don't dedicate all of your energy toward money-making projects. You get involved in a lot of advocacy, and collaborative projects like this. Like this food project, I'm sure it wasn't money-driven, yet you have achieved a lot of success in your practice.

If you were to offer advice to someone coming up and starting their own practice, do you feel that these opportunities that you have to engage with the community,to do things that feed your soul rather than your bank account, are the things that should happen first and then the work comes out of that? Or, would you recommend prioritizing paid work, to allow for opportunities to work on charitable work?

My advice to young professionals is to follow your passion. This is the kind of profession that you can only do because you love what you do and because you see the opportunities of really interesting experiences. I've had people that I've had to have a conversation about, like, look, this is not a 9 to 5 job. There are occasions where we all go and do something on a Saturday because it's a community workshop or I like to encourage people to participate in nonprofits, to volunteer. More often than not, people come to work with us who have that curiosity and that interest.

So what I would say is obviously you have to pay your bills. But I would say that, especially now with the Internet and the ability to communicate digitally, that as designers and people with the training that we get, that there's a lot you can do and offer. You know, right now, a lot of people could be involved in elections in the future or what about the homeless issue? What about doing a project or two here and there through your council office that might help people who are on the street? And I don't mean giving them food, but is there a design solution in a parking lot that we could be working on?

Do you consider that a responsibility of a creative professional to take those skills and apply them?

Absolutely, absolutely. I think so. You shouldn't go for solace or for nurture to a place of prayer and just think that's enough. I think there's more you can give and it's so easy to give, especially when you have our training. I feel like you have an obligation.

Paul Petrunia is the founder and director of Archinect, a (mostly) online publication/resource founded in 1997 to establish a more connected community of architects, students, designers and fans of the designed environment. Outside of managing his growing team of writers, editors, designers and ...

Sean Joyner is a writer and essayist based in Los Angeles. His work explores themes spanning architecture, culture, and everyday life. Sean's essays and articles have been featured in The Architect's Newspaper, ARCHITECT Magazine, Dwell Magazine, and Archinect. He also works as an ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.