When we speak of contemporary Mexican architecture, there are a handful of firms that take up most of the global spotlight. Architects such as Frida Escobedo and Alberto Kalach have created much buzz within the profession in recent years, for example, the former for snagging the commission for the 2018 Serpentine Pavilion and the latter for having spent several consecutive years at the top of speculative Pritzker Prize lists.

Though both of these firms, along with nearly all of their renowned contemporaries, are based in Mexico City, there is a lesser-known—though just as intriguing—design scene brewing North of the country’s capital. Let's check it out.

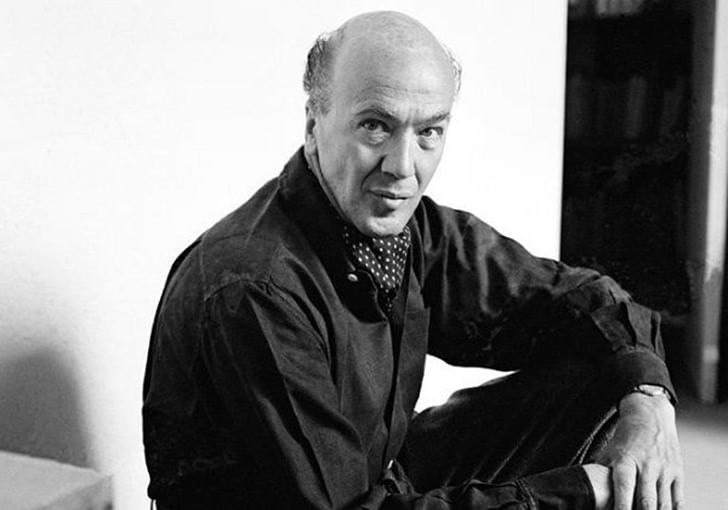

Guadalajara, Mexico’s second-largest city, is home to a rich architectural history that spans several centuries. Perhaps its most relevant era, however, begins with the so-called Escuela Tapatía de Arquitectura, a movement that took place between 1926 and 1936, and was led by one Guadalajara native who would later become a diamond (though that’s a story for a separate occasion), as well as Mexico’s most famous architect: Luis Barragán.

The Escuela Tapatía de Arquitectura—or Tapatía Architecture School, the first word meaning “hailing from Guadalajara”—was inspired by Ferdinand Bac, a French architect, landscaper, and consummate aesthete whose work on building-encompassing gardens, simple forms made of local materials, and a distinct “modern Mediterranean” style fascinated Barragán immediately when he discovered it 1925 while visiting Paris. Along with fellow architects such as Pedro Castellanos, Aurelio Aceves, Rafael Urzúa, Enrique González Madrid, and Juan Palomar y Arias, Barragán set out to establish a formal language in Guadalajara that was rooted as much in Bac’s teachings as in the local vernacular.

The Tapatíos were enamored by artisanal traditions, and the movement came to be characterized by stark geometries, locally-sourced materials, patios, ample hallways, fountains, and the blurring of interior and exterior spaces, a predilection facilitated by Guadalajara’s perpetually forgiving climate. Sound familiar? It should, because Barragán carried a fondness for these elements with him years later, when he moved to Mexico City and produced the later half of his oeuvre. Today, these approaches can still be observed in the prominent buildings that placed the architect on the map, and added a Pritzker Prize to his mantle.

“The Tapatía Architecture School took the lessons of international Modernism and adapted them to local constructive systems, materials, and cultural customs,” says Laura Barba, adding that “this pursuit to marry the vernacular and contemporary has influenced our work enormously.”

Fast-forward a few decades later, the teachings of the Tapatía Architecture School continue to reverberate within the contemporary structures being erected by a new generation of architects in Guadalajara. Studios such as Macías Peredo, Villar Watty Arquitectos, Luis Aldrete, and Diagrama Arquitectos share more than their geographical placement; each studio has established a distinct design language that is deeply rooted in the legacy of their predecessors, while still responding to the contemporary living conditions of Guadalajara in the 21st century.

Founded in 2012 by Magui Peredo Arenas and Salvador Macías Corona, architecture studio Estudio Macías Peredo Arquitectos quickly developed a distinctive aesthetic, drawing from regional craft traditions and employing locally-sourced materials to create projects that channel traditional approaches through contemporary design.

As keen observers of Guadalajara’s history, climate, and social context, they strive to give continuity to local traditions, making their architecture one that is concerned more with processes of introspection and self-reflection than with the innovative forms and tech-savvy construction mechanisms that characterize many foreign architecture practices.

Luis Aldrete Arquitectos has designed a slew of projects in Guadalajara and other areas of the state of Jalisco. His works include a structure that serves as a refuge for pilgrims making their way along La Ruta del Peregrino to visit the Virgin of Talpa; the Rinconada Margaritas Residential Complex, a high-rise residential project; and several private homes that, though doubtlessly contemporary, include elements such as long corridors and interior patios that are typical to the region’s old haciendas.

For Aldrete, being able to work in close proximity to master artisans is one of the biggest advantages of living in Guadalajara, as opposed to Mexico City.

“There is a distinctively Tapatío approach to architecture that comes from the legacy of Barragán, and my generation certainly displays its influence,” says Alberto Villay Watty of Villar Watty Arquitectos, which he founded with his brother Gerardo in 2011, “though in our case it is undeniable that we have also been influenced by foreign architecture.”

The studio’s work—which spans from single-family homes to residential and commercial towers—is characterized by a deliberate focus on creating environments that evoke a sense of mystery, as well as warm and tactile spaces that call to be experienced in person, rather than through flashy photographs.

“The local culture in Guadalajara responds in many ways to its idyllic climatic conditions,” adds Villar Watty, “people enjoy open spaces, and our architecture, in turn, responds to that affinity.”

The intention to merge interior and exterior spaces is also a cornerstone of their practice. “The local culture in Guadalajara responds in many ways to its idyllic climatic conditions,” adds Villar Watty, “people enjoy open spaces, and our architecture, in turn, responds to that affinity.”

“I think the one thing we always try to achieve through our practice is to generate a sense of belonging in our building’s inhabitants,” says Laura Barba, who directs Diagrama Arquitectos alongside her partner Luis Aurelio Piña. Having attended architecture school in Guadalajara, where they have continued to live and work, the pair developed a profound interest in the architectural history of both the city and the rural areas that surround it.

“The Tapatía Architecture School took the lessons of international Modernism and adapted them to local constructive systems, materials, and cultural customs,” says Barba, adding that “this pursuit to marry the vernacular and contemporary has influenced our work enormously.”

Ranging from commercial and residential towers in Guadalajara to a small hotel in Baja California, to buildings located within the jungle of Quintana Roo, the work of Diagrama Arquitectos aims to evince the weather conditions, collective memories, and constructive traditions of a place, establishing a dialogue between their architecture and its immediate context.

1 Comment

Great well-written article. Would love to see your top must read books to give a novice an introduction to architecture and design in Mexico

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.