Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill are three names hardly unrecognizable. Still one of America’s largest architecture practices and pioneers of the modern skyscraper, but how did it get its start? Better yet, who is Skidmore? And who is Owings? How about Merrill? And how did the three meet? What is the story behind one of America’s most important practices? It is a story few have told and even fewer know, one filled with twists, turns, and unexpected surprises.

Skid, the Learned Man

Louis Skidmore (a.k.a Skid), as a young man with a fascination in architecture, began his hand as an engineer, studying electrical engineering at Bradley Technical College in Peoria, Illinois. But World War I called the aspiring student to arms. After graduation, he joined the Air Corps in England. As he arrived in Liverpool with the other young troops, Skidmore would have seen the Liverpool Cathedral which was still under construction (Adams 19). It was a large gothic structure designed by the eminent English architect Giles Gilbert Scott. With a project timeline of just over seven decades and one of the largest cathedrals in Britain, the project provided a symbolic foretelling of the soldier’s future influence in architecture.

Coincidentally, when Skid, the veteran, returned home, he began working for the old Gothic firm, Cram and Ferguson, in Boston. As he developed his chops as a draftsman during the day, he attended the Boston Architectural Club (BAC, now known as Boston Architectural College) at night. The BAC was a place where professionals could take difficult design problems and receive feedback from Harvard and MIT professors. Skid wanted to grow and took advantage of the offering, and as he worked on his skills, they became stronger. Soon, he won a prize at the BAC and was awarded admission to MIT, where he studied until 1924.

In 1926, after he’d been working for about eight years, and with the help of his mentor William Emerson, the first dean of the MIT School of Architecture, Skid won the Rotch Traveling Fellowship. With two years of unrestricted travel at his disposal, the 29-year-old went off to Paris.

While he was in Europe, Raymond Hood, the acting Head of the Design Board for the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933, and later responsible for Rockefeller Center tracked him down and urged him to join the Expo’s design team. He was eager to have the emerging professional on his crew.

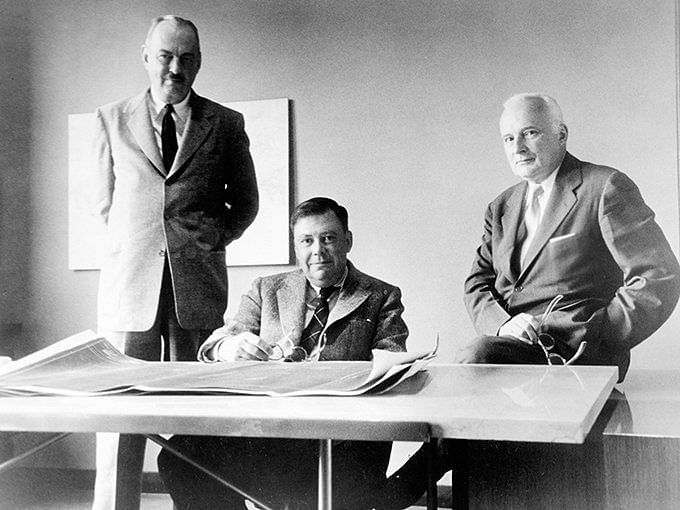

...the two would build one of the largest and most significant American architecture firms of the twentieth century.

With a job offer and glimpse into his future, Skidmore also had love on his mind. He met a young woman named Eloise while in Europe. The two hit it off and returned to the States together. In 1930 they solidified their relationship in marriage and through the matrimony, Skid also gained a new brother. Eloise Owings had a sibling, and his name was Nathaniel Owings.

Nathaniel had first studied architecture at the University of Illinois, but then left after becoming ill. He later finished his education at Cornell in 1927 and then went to work at York & Sawyer as his first job. His newfound brother would later become his business partner, and the two would build one of the largest and most significant American architecture firms of the twentieth century.

Newly married and back in the U.S., Skid took Raymond Hood up on his offer and joined the Design Board for the Chicago World’s Fair as a junior designer. All was well until one day, General Rufus Dawes, the overseer of the Expo, fired all of the architects on staff. Hood also decided to step down as head of the Design Board, leaving an inexperienced Skidmore as the new man in charge. With his only option to step up and make the best of the debacle, Skid’s first move as leader was to hire his brother-in-law, Nathaniel Owings, to help him with the task ahead.

The Chicago World’s Fair of 1933 was entitled A Century of Progress, and its goal was to celebrate the achievements of industry and science (Adams 19). The professor and historian Nicholas Adams explains it best:

“the...Exposition had to encompass a diverse group of interests. There were few pavilions to represent foreign countries or folk customs, a few to explain programs of the U.S. government, and there were, of course, rides and entertainment. Most of all, however, there were pavilions representing American industry...the Century of Progress was intended to look forward, embracing the achievements of science and industry and offering a decidedly modernist vision of the world to come.”

With a 12 million dollar budget, Nat and Skid had to lay out an entire city that included a transit system and entertainment attractions for up to thirty million visitors.

With a 12 million dollar budget, Nat and Skid had to lay out an entire city that included a transit system and entertainment attractions for up to thirty million visitors. In his autobiography, Owings remembers the speed with which he had to “become an expert in many fields” and the tremendous responsibility that was suddenly thrown upon him and his partner. He goes on about how he “made up in enthusiasm for what I lacked in skill.” The pair soon developed an agile team of their own and undertook their inherited duties with poise and persistence.

Skidmore and Owings each had distinct personalities that, in terms of business, complemented the other. With irresistible charm and an uncanny ability “to win over even sworn enemies (Adams 19),” Nat was the perfect candidate for organizing and entertaining clients. During the Expo, he was involved in constructing the buildings and managing special events but was also in persuading other architects and engineers to help with the work (Adams 20). Skid, on the other hand, paid very close attention to detail. He solidified the vision and concept of the exposition to exhibitors and their architects, showing them the value of architecture to their businesses. He got to know many big players (such as Westinghouse and Heinz) who had money, and within the Expo, he had power and control over all of them.

What started as an operation run by amateurs became a melting pot for tremendous and rapid growth. As Nicholas Adam puts it: “the lessons of the exposition proved invaluable.” The experience allowed the pair to learn what big businesses wanted from an architect and how they could provide it. Moreover, as in the case of Skidmore’s invitation from Hood in Paris, they would learn the irreplaceable power of good relationships, something that would secure the duo many coveted commissions in their future.

When A Century of Progress ended in 1934, Nat and Skid went their separate ways. Owings and his wife, Emily Hunting Otis (whom he had met in 1931 while in Chicago), went to Vancouver and then traveled around the world (Adams 20). Skid and Eloise settled at home and in that same year welcomed their first child, Louis Jr. After about a year, in 1935, the two couples met up in London, where Owings and Skidmore, ready for a new chapter, made an oath to one another.

The new business owners opened their first office at 104 South Michigan, Chicago on the 1st of January 1936 in an attic that "everyone referred to as 'the penthouse.'"

“Skid and I pledged our lives to share and share alike — to offer a multi-disciplined service competent to design and build the multiplicity of shelters needed for man’s habitat. We would build only in the vernacular of our own age,” Owings reminisced about the day. It was with this that the architectural firm of Skidmore & Owings was born. The new business owners opened their first office at 104 South Michigan, Chicago on the 1st of January 1936 in an attic that “everyone referred to as ‘the penthouse.’”

Like most young start-ups, the first year for Skidmore & Owings was rough. The economy was still getting back its bearings, and even the big firms in Chicago were struggling to get by; they needed to find work. The logical first step was reaching out to the network they had built during A Century of Progress. Soon, they connected with Rufus Dawes, the former president of the Expo who had fired his entire team of architects. Luckily, he had work for them — to renovate the Palace of Fine Arts, initially designed by the architect Charles B. Atwood. The building was originally part of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. “Inside, the young architects built a mechanized coal mine and dynamic exhibits that led to increased admissions,” writes Nicholas Adams. The firm of Skidmore & Owings was already providing its patrons a good return on their investment.

But one project was not enough; the pair needed more work. Owings’ father-in-law, Joseph E. Otis, who was on the board of a Community Hospital in Michigan, also pulled together some jobs. The board commissioned the partners to “undertake construction of a 100-bed facility completed in 1939 (Adams 21).” They also took on several smaller projects ranging from the renovation of an office for the president of United Airlines to the design of a visitors’ path through the Wilson Meat Packing Plant. Skidmore and Owings were eager to nail down projects and continue growing their business.

Soon, Owings reconnected with another colleague from A Century of Progress — Raymond Hood. He was given the opportunity to design a product display in Hood’s Radiator Building in New York. The only caveat was that his firm needed to have a New York office and a resident partner (pg 21). There was no New York location or resident-partner, but Owings was not going to let the project slip through the cracks. After the meeting, he promised to send over a letter “not later than tomorrow morning” meeting the criteria.

Running from the Radiator Building, Owings made his way to a local department store to look up the address of two friends, Joseph Urban and Otto Teegan, who owned a local firm. He created a letterhead and put Skid’s name on it as resident partner, with Skidmore & Owings’ New York address becoming the same space that was used by their friends Urban and Teegan at 5 East 57th Street (Adams 21). Thus, Skidmore & Owings New York got its start.

For Skidmore and Owings, the right relationships produced the right opportunities.

Shortly after, Skid trekked east to New York and began to build his new team, a group of architects, who became known as “Skid’s boys.” They would run the company’s New York office for the next thirty years. There was Robert W. Cutler, who specialized in hospitals; J. Walter Severinghaus, who had experience in housing; and Gordon Bunshaft, the designer who would go on to win the Pritzker Prize in 1988. In addition to solidifying his inner circle, Skid also became friends with Robert Moses, the president of the New York State Parks Council and the Long Island State Parks Commission. He is the subject of the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography The Power Broker.

Moses would soon go on to become one of the most powerful men in New York. He had his hand in pretty much every major construction project in New York City and blessed his new friend with a seat as resident architect on the Long Island State Park Commission Board. As a result, Skid received the bulk of the city’s housing and civil engineering projects and the commission for the New York State Complex within the New York World’s Fair of 1939. For Skidmore and Owings, the right relationships produced the right opportunities.

The New York World’s Fair gave the duo a second opportunity at expo design and further elevated the power and network they had already begun to amass. Skid became a consultant to the general manager and chief engineer of the fair and soon revisited talks with the business leaders he had worked with years prior. New patrons who wanted to work with him presented themselves and those eagerly seeking his counsel “usually ended up paying a thousand dollars for a preliminary idea which he would suggest for their exhibit (Adams 22).” All in all, S&O was responsible for the design coordination and site planning in addition to the design and construction of 8 pavilions, the most famous of which was the pavilion for the Republic of Venezuela, designed by a young Gordon Bunshaft (Adams 22).

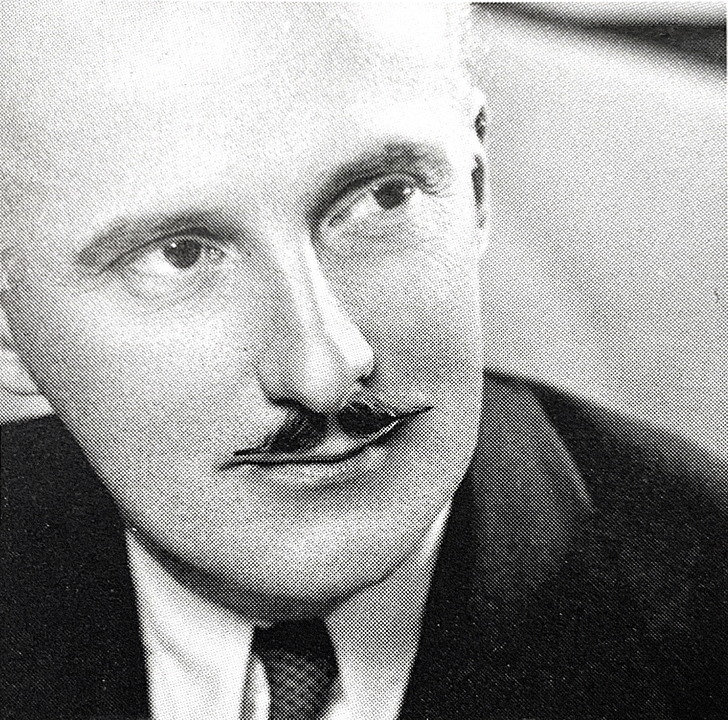

Gordon Bunshaft outside the Beinecke Rare Book Library. Image courtesy of SOM.

Gordon Bunshaft was a gifted designer and far surpassed everyone at Skidmore & Owings. For forty-two years he reigned as design leader and eventually won the Pritzker Prize. Like Skidmore, he was an MIT alum, having received his B.Arch in 1933 and his M.Arch in 1935. He was also awarded the Rotch Traveling Fellowship, receiving the same two years unrestricted travel as Skid did some years prior.

From 1935 to 1937, he took an exploratory approach, traveling to Paris, Rotterdam, Hilversum, and Stockholm, seeking to absorb as much as he could (Adams 22). It was after his travels that he began his career at Skidmore & Owings, working primarily out of the New York office.

...he approached architecture with the instincts of a fox, drawn from scent to scent.

Bunshaft was deeply influenced by Le Corbusier and wasn’t particularly adept at staying true to styles. As Adams puts it, “he approached architecture with the instincts of a fox, drawn from scent to scent.” He had a gift for sussing out the best solution for a problem. Bunshaft was responsible for almost every major project at Skidmore & Owings (and still later, Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill).

There was the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale, the Hajj Terminal at King Abdulaziz Airport, the Solow Building in Manhattan, and countless others. His creative prowess helped establish a legacy like none before. But design can only go so far. From the beginning, Nat and Skid had pledged “to offer a multi-disciplined service,” and it was time to move the firm into its next chapter, one that would require the addition of a new partner.

Like Skidmore, John Merrill also served in WWI, but as a Captain with the Coast Artillery (Times). He studied civil engineering at the University of Wisconsin and promptly graduated into the war in 1917. After his release from the military in 1919, he went to MIT to study architecture, receiving his degree in 1921. His eventual invitation to join Skidmore & Owings was strategic; the New York location was booming due to Skidmore’s friendship with Robert Moses and his position as resident architect on the Parks Commission, and also because of the unique talent of Gordon Bunshaft.

But, in 1936 the firm was beginning to strengthen its presence in Chicago with some government housing commissions — Merrill had experience with this. He was also pivotal in transforming the firm into an architecture AND engineering practice. S&O was now SOM, and the initial vision of a “multi-disciplined” practice had been realized. Skidmore, Owings & Merrill were ready for their next chapter.

If one thing is certain in this origin story, it is the role of chance and the tremendous opportunity it brought the founders. Almost every factor in Skidmore and Owings’ slow rise to prominence happened by chance. Skid receiving the Rotch Fellowship and traveling to Europe is probably the greatest of all. It was there that he connected with Raymond Hood and was offered a seat at the Chicago World’s Fair, where he met his wife, Eloise, and in turn his new brother Nathaniel Owings.

There was also Rufus Dawes’ firing of the entire design team at the World’s Fair and Hood’s subsequent resignation that left Skidmore with his hands up to figure everything out. Here he rose in power almost overnight and brought in Owings to join him. Even further, this position allowed the pair to build an invaluable network and pushed them to become masters at the management and design of a project of almost the grandest scale, positioning them perfectly for the New York World’s Fair of 1939. We must also not forget that Skidmore happened to become close friends with the most powerful man in New York, Robert Moses, who raised him even further in power and bestowed upon him many sought after commissions.

As they had seen historically, the firm would only continue on its trajectory forward. After the New York World’s Fair and the addition of Merrill as “partner-in-charge of engineering,” the firm’s Chicago location began to boom with the acquisition and execution of many significant government housing projects. The increase of construction costs for the organization since its start in 1936 to 1941 went from $3.300 million to $14.615 million, a growth that would continue to steadily increase. Fast forward seven decades to 2017 and we see the firm holding a 12th place national ranking with an annual revenue of $333.9M, according to Architectural Record.

In 1942 they would receive the contract to design Oak Ridge, a secret city in Tennessee, one of the birthplaces of the atomic bomb, and home to thousands of people. “The Manhattan Project’s leader, J. Robert Oppenheimer, wanted SOM to make the houses livable enough to convince academics who wanted a cushy, suburban lifestyle that they should come work for the government,” writes Katharine Schwab of Fast Company. The project allowed the firm to tap into its experience from the two previous World’s Fairs, and with a $160 million construction budget, launched them into a completely new stratosphere.

As the company moved into the 21st century, they became well associated to the modern skyscraper with structures like the Burj Khalifa in Dubai (2009), the John Hancock Center in Chicago (1969), the Sears Tower, also in Chicago, and more recently, One World Trade Center in New York (2013). Today, SOM has completed countless projects and have consistently been a kind of incubator for the careers of many great architects with names such as Natalie de Blois, Adrian Smith, Bruce Graham, and David Childs. What started as two brothers scrambling to learn the ropes, years later, has become one of America’s most influential architecture practices. As they say, the rest is history.

___________________

Works Cited

Bunshaft, Gordon. “Bunshaft - On SOM.” www.SOM.com , 2009, web.archive.org/web/20090820183656/http://www.som.com/content.cfm/gordon_bunshaft_interview_on_som.

“Introduction: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill 1936-2006.” Skidmore, Owings & Merrill: SOM since 1936, by Nicholas Adams, Electa Architecture, 2007, pp. 19–58.

Owings, Nathaniel Alexander. The Spaces in between; an Architect's Journey. Houghton Mifflin, 1973.

Schwab, Katharine. “See the Top-Secret Suburbs That Built America's Nuclear Weapons.” Fast Company, 9 July 2018, www.fastcompany.com/90175737/see-the-top-secret-suburbs-that-built-americas-nuclear-weapons.

Shenker, Israel. “John Merrill Sr., Architect, Dead.” The New York Times, 13 June 1975.

Sean Joyner is a writer and essayist based in Los Angeles. His work explores themes spanning architecture, culture, and everyday life. Sean's essays and articles have been featured in The Architect's Newspaper, ARCHITECT Magazine, Dwell Magazine, and Archinect. He also works as an ...

11 Comments

Thanks for the article. Funny how you forgot to mention that the company (SOM) has also been a place where many women’s careers go to die, as they are being paid 2/3 of what their male counterparts are being paid. You forget to mention that just recently, under the partner Roger Duffy, the record number of women has quit, since the glass ceiling for a women designer at SOM is what they used to call an E level- very close to an associate, but never the associate. The HR woman, who still works there was is basically Roger’s fixer. Roger’s boys continue to design dildonic towers in China. What a great legacy!

I don't really understand these types of comments - what is preventing you from writing your own alternate history of SOM highlighting these issues you seem to care deeply about? (Though not so deeply you would take the initiative to foreground them)

I guess it’s not clear from my comment but I tried and failed. What is one architect against a corporate behemoth? But I will not stay silent when they are praised in architecture publications. I hope you understand that.

Its a well known fact that SOM is like an Old Boys Club. But this is then true of a lot of old large architecture firms. Its too bad we glorify these Old White Boys the way we do.

Did you bother to read the title of this article?

amazing how much more designers could do with a pen and paper — the visions were much bigger and bolder but more artistic. Even a firm like SOM had a strong design ethic — three blind mies

I have to side with Elektrikcat on this one. The article makes no mention of Natalie de Blois FAIA who was an original member of the NY office in the late 30's. While she garners a special mention in Nathaniel Owings memoir, she was never made partner despite her storied tenure at the firm. I was lucky enough to study with her in the 90s.

Thanks for the comment. I don't think it is a matter of taking a side. Both you and Elektrikcat bring up very relevant, valid, and important points. This article's focus is specifically on the three named partners and their early experiences which doesn't seem to hide the clear male dominance of the profession as a whole during that time. It is merely a (brief) historical account of how those three met.

That’s amazing that you had the opportunity to study with du Blois (who is mentioned in the closing of this article and who we’ve been wanting to learn more about). We’d love to hear about your experience with her if you’d be okay sharing. Send me or our Managing Editor, Antonio Pacheco a message, if that’s something of interest to you.

Sadly, minorities (both gender and ethnic) in architecture are vastly underrepresented historically. Something, that I myself as a minority and the rest of us here at Archinect have been working to tackle and address.

You may find this thread that Antonio started of interest. We’re trying to work with our audience to address a lot of these issues as well:

https://archinect.com/forum/thread/150161117/pioneering-female-architects

Thanks again for your comment!

You make a good point, the article is about the firm and its founding partners. I have a great deal of respect for the firm and have had many great experiences working with SOM in both the San Francisco and Los Angeles offices. My observation was really about a great architect that most have never heard of despite her significant role on many SOM legacy projects. As an aside, she was also the first woman to graduate from Columbia GSAPP.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.