It’s an open question whether the Southwest Museum of the American Indian in Los Angeles has its best days behind or ahead of it.

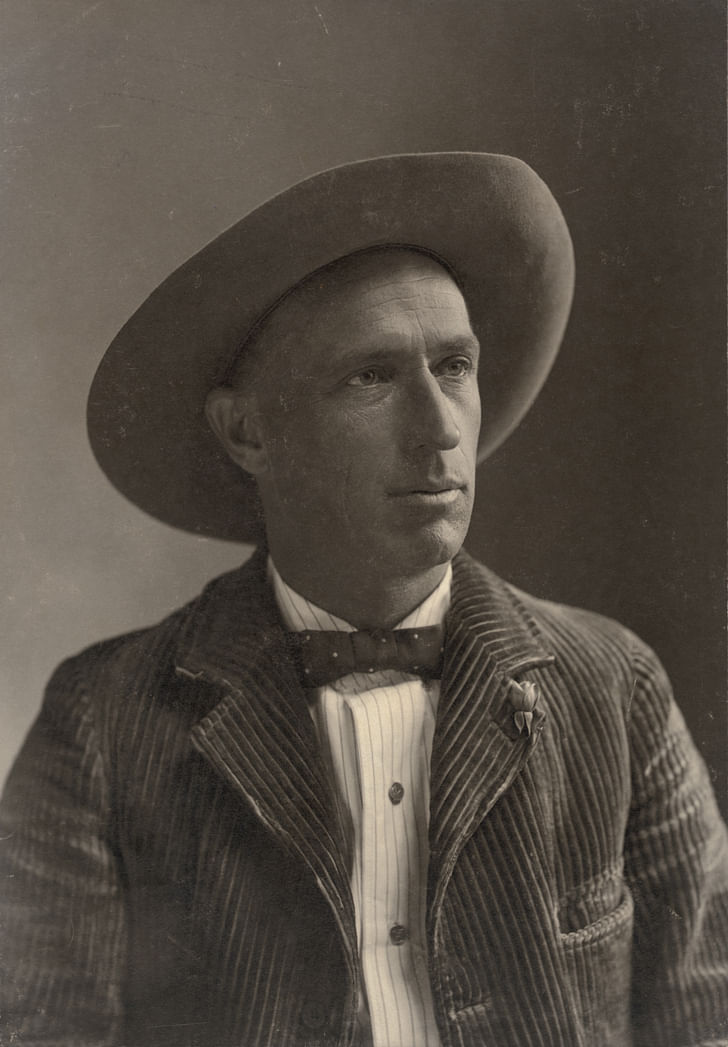

The Spanish Colonial Revival-style mountaintop campus was built in 1914 by architects Sumner P. Hunt and Silas Reese Burns at the behest of anthropologist, historian, journalist, and photographer Charles Fletcher Lummis. Lummis, founder of the Southwest Society, the west coast branch of the Archeological Institute of America, created the museum several years earlier in Downtown Los Angeles to highlight a vast collection of Native American cultural artifacts he had acquired while traveling through the American Southwest. The museum, dedicated to supporting the “history, science, and art of the American Southwest,” contains the largest and one of the most important collections of Native American cultural artifacts in the country.

Today, it also exists today mostly as a shell of its former self.

Suffering from years of deferred maintenance, in need of seismic retrofitting, and, in recent years, largely empty of its sizable collection and archives, the museum has certainly seen better days in its 105-year history. Following the 2003 merger with the Autry Western Heritage Museum—now known as the Autry Museum of the American West—many of the Southwest’s collections were removed to an off-site facility for cataloging, preservation, and restoration.

Today, a few exhibits of indigenous pottery remain installed for the public to enjoy on a limited basis, but otherwise, the sprawling cast concrete acropolis sits gathering dust.

That's where a dedicated, interdisciplinary team headed by the Autry and the National Trust for Historic Preservation has come in to try and breathe new life into the complex.

In March 2019, The Autry announced that it is seeking organizations to propose “innovative and financially sustainable concepts for the revitalization and creative reuse” of the Southwest Museum campus and the adjacent Casa de Adobe complex through a Request for Interest (RFI) call.

Predating The J.Paul Getty Museum by some 80 years, the Southwest Museum is the area’s original hilltop cultural institution, a fact that has both helped and hindered its cause over the years. And though the museum’s smooth stuccoed walls and punched arched openings don’t look out of place today, when it was first built, the cast concrete structure represented a vision for a new California that was shaped in equal measure by both the plastic industrial materials that gave it form and by the budding aesthetic sensibilities of Manifest Destiny that lent those classicizing forms meaning.

Lummis, a complicated and largely problematic figure who captivated American audiences with syndicated writings detailing his spectacular on-foot adventures through the American Southwest, is widely considered one of the leading voices of early Los Angeles boosterism following the transfer of California from Mexican to American dominion. His writings romanticized the quickly-fading Mexican and indigenous cultures that had occupied the area for generations. These works depicted the exciting and exotic existence awaiting Americans, should they choose to move westward, and in doing so, also helped fuel Los Angeles's prodigious population growth at the time. Loomis's documentary efforts, on the other hand, worked to preserve indigenous ways of life by marketing these cultural practices, aesthetics, and artifacts for popular consumption. As Los Angeles doubled in population over the few short years following Lummis’s arrival, its transplanted Anglo populations looked to the newly-minted Spanish Colonial Revival style as a way of lending their recent and expansive territorial acquisitions the appearance of authenticity. A product of its time, the Southwest Museum complex was designed with this style at its forefront. Capped by a distinctive crenelated tower surrounded by smaller red tile roof-topped masses, the museum is designed to evoke both the Alhambra in Spain and the historical pastiche-laden California Missions that country’s colonizers built here when they arrived, and represents a key work in the Spanish Colonial Revival style.

Today, those connections are easier to miss, but Lummis’s appropriative curatorial approach is still apparent around the complex, where until recently, various styles and eras of architecture were brought together to display equally varied sets of objects.

The museum, for example, is accessed from ground level by a Mayan Revival-inspired triumphal archway that was added years after its official opening. Before that, visitors were expected to hike to the top of the hill and commune with the 12-acre site in preparation for experiencing the collections. The Mayan portal is inspired by the ruins of Chichen Itza—Lummis traveled throughout Mexico and Central America extensively, as well—and leads to a long tunnel lined with two dozen niches that at one time held evocative dioramas depicting scenes of indigenous life. At the end of the tunnel, a rickety 1970s-era elevator lifts visitors four or five at a time to the museum’s main level above, where a grand hall filled with paintings and artifacts showcases a few of the museum’s remaining works. Two levels of symmetrical halls are arranged around this central lobby, with each of the exhibition rooms formerly dedicated to showcasing the works of a different regional population. On each extreme end of the building, an off-center tower contains auxiliary display, research, and conservation areas. The cast-in-place Caracol tower on the far eastern end of the complex, for example, is capped by a defensive parapet and is filled with a winding, coiled concrete stair that gives the spire its name. Lummis once kept an office at the top of the tower, where double-height, raw concrete spaces offer mile-long vistas as well as surprisingly roomy accommodations for those who can complete the ascent.

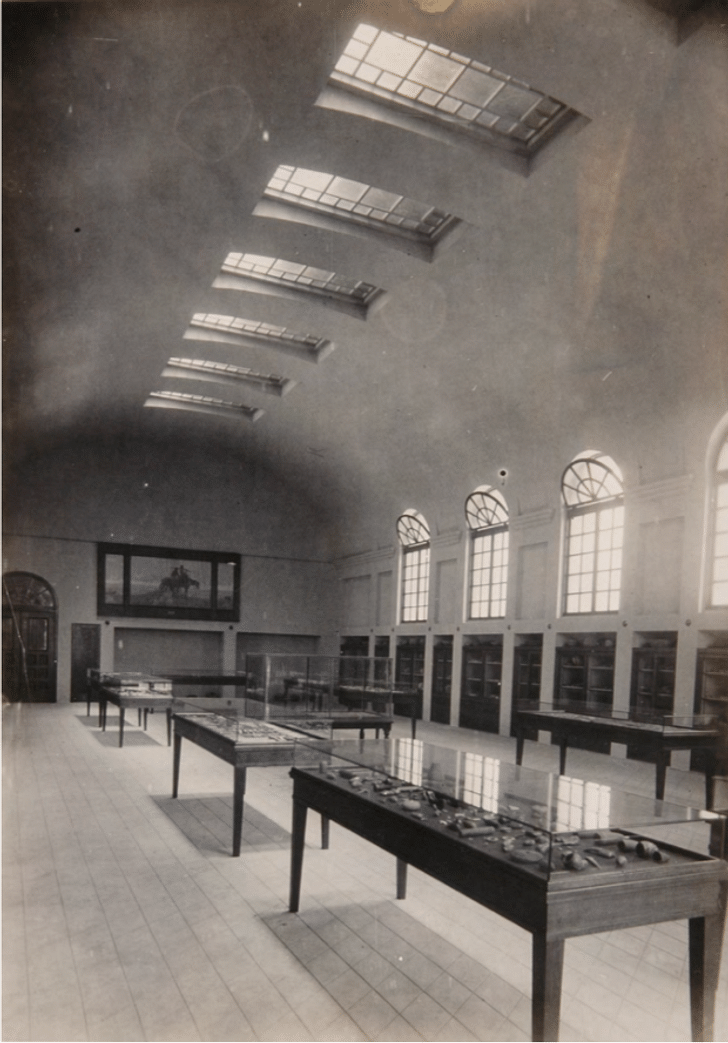

A squatter tower on the opposite end of the building is more pragmatic in its configuration and contains research and other back-of-house areas that are lit from above by a series of skylights.

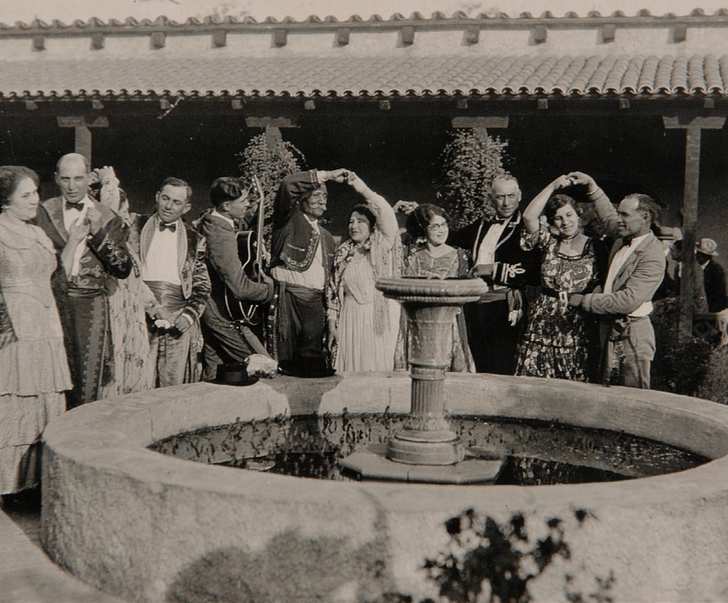

The front of the main building, meanwhile, is framed by a broad terrace that provides its own spectacular views of the city stretched out below. It was here, a century ago, where Lummis held raucous parties, including California-specific art salons Lummis referred to as “noises,” for the museum and its patrons.

Lummis died in 1928, but his museum would continue to live on and change long after his death.

In 1941, Los Angeles architect Gordon B. Kaufmann, designer of the Hoover Dam and The Los Angeles Times building, crafted a transverse addition to the complex that provided dedicated exhibition spaces for the museum’s extensive basket collections. The stately two-story building is marked along its lower level by grid of columns and by large picture windows. On the level above, a clear-span second floor features light-giving clerestory windows situated underneath a projecting red tile roof.

Later, in 1971, architect Glen E. Cook created a third building that completes a central courtyard between the existing wings. The spartan Braun Research Library wing, a spare CMU-building wrapped in cream-colored stucco and topped with a hipped tile roof, is perhaps the least grandiose of the structures. The necessary building used to house delicate texts and archival materials under climate controlled conditions, but is now partially-emptied. The two-story structure, windowless and filled with vintage wall-to-wall carpeting, is not your average preservationist’s idea of a historic building, but it is recognized, along with the remainder of the complex, at the local and national levels as a key historic site.

Aside from its status on the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s National Historic Register, in 2015, the complex was listed on the National Trust’s list of National Treasures list. It is eligible for state-level listing in California, but an application has not been put forth.

With this multifaceted history in the rearview mirror, and the Autry’s collection cataloging efforts recently completed, the Southwest Museum lies in wait, poised for a new lease on life.

That’s because a collection of organizations, including the Autry, the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Los Angeles office, the City of Los Angeles, and potentially, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, are working together to harness the potential of the Southwest Museum site as a community-focused development opportunity. In March 2019, The Autry announced that it is seeking organizations to propose “innovative and financially sustainable concepts for the revitalization and creative reuse” of the Southwest Museum campus and the adjacent Casa de Adobe complex through a Request for Interest (RFI) call.

The RFI call, due June 10th, follows exhaustive outreach efforts on the part of the National Trust for Historic Preservation over the last four years. The Trust’s outreach has included community surveys, a year-long event series aimed at drawing new audiences to the museum, and the formation of a 15-person steering committee that includes members of the Los Angeles Conservancy, city officials, and other preservation professionals aimed at guiding the visioning process.

In a press release announcing the RFI, Chris Morris, National Trust Senior Field Director for the Los Angeles region, said, “The beauty and history of the Southwest Museum site is unmatched in Southern California. We are pleased to continue our long-term partnership with the Autry to realize sensitive and creative uses that will mark an important new chapter for this place that is such an integral part of the Northeast LA community.” Morris added, “We know that the best partner for this type of project is one that brings innovation along with experience, a deep respect for historic buildings, and an overarching desire to be a good neighbor.”

Morris added, “We know that the best partner for this type of project is one that brings innovation along with experience, a deep respect for historic buildings, and an overarching desire to be a good neighbor.”

Not quite a full-blown Request for Proposals, the RFI call is instead intended to gage the potential interest for the site from the development community while also hopefully fielding a bevy of new and innovative ideas for the complex. Officials in the city and county governments are watching the process to see which groups and organizations come forward as potential partners, for example, while, as Morris explained during a recent American Institute for Architects, Los Angeles chapter tour of the site, the National Trust is hoping to hone in on “the right use or set of uses” for the site moving forward.

According to a visioning document, the RFI process is guided by a so-called “Four Cs” approach that unifies a commitment to preserve the site with a demonstrable organizational and financial capacity for undertaking the project, a willingness to support community concerns, and a vision that draws on the Autry’s collections.

Some of the potential uses listed in the RFI document include repurposing the site as gallery or museum space, the addition of live/work spaces for short-term artist or scholar studios, the inclusion of commercial ventures like restaurants, cafes, educational programming, performance spaces, and even, “limited-scale residential uses.”

The complex, the National Trust boasts, is ideally situated to take advantage of many beneficial development incentives, including Federal Historic Preservation Tax Credits, Mills Act Program initiatives, key preservation easements, as well as the New Markets Tax Credits program.

In fact, any group that takes on the project will surely have their work cutout for them, as the owner of any 100-year old building can tell you. Aside from conventional issues old building issues, the complex has limited Americans with Disabilities compliance, especially to some of the more singular elements of the site like the towers and main terrace.

Some of the necessary seismic retrofits have taken place—the Caracol tower, for example, has now been more rigidly adhered to the main building mass so that they can sway together during seismic events—but other structural issues of the sort remain. HVAC issues abound, as well, as one can image for a building designed decades before forced air technology became prevalent. The main galleries in the original building are prodded with vents and ducts while picturesque Palladian windows sit boarded up. Also, many of the original openings in the back-of-house areas have been bricked in, a function of the growing extent of improvised environmental control efforts undertaken for a building designed to be naturally lit and ventilated.

Ultimately, however, for the right partner and program, the project could be a perfect fit, as well as an opportunity to resuscitate an aging but vital cultural complex. The Autry and National Trust are surely keeping an opening mind. As the Trust's Morris explains, "We are open to a wide range of ideas as long as they respect and respond to the '4Cs' that we define in the RFI."

Antonio is a Los Angeles-based writer, designer, and preservationist. He completed the M.Arch I and Master of Preservation Studies programs at Tulane University in 2014, and earned a Bachelor of Arts in Architecture from Washington University in St. Louis in 2010. Antonio has written extensively ...

1 Featured Comment

This facility needs to be brought to life in the 21st century. The collection will be well cared for at the Autry, but this place should be turned into a performance venue focused on native western hemisphere cultures. Lumis would approve.

All 2 Comments

It would be very exciting to participate in a project aimed at breathing new life into a cultural institution that once housed so much history and evidence of the people who were the first Americans. The information in this article about the “Mixed History” is extremely fascinating.

This facility needs to be brought to life in the 21st century. The collection will be well cared for at the Autry, but this place should be turned into a performance venue focused on native western hemisphere cultures. Lumis would approve.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.