A note to the reader

This text is more of a curated/comprehensive overall picture, to question the role of robot—precisely what is known as “industrial” robot arm, in our current days as possibly a medium, instead of—just, a tool. The text, however, does not look at this issue from a purely historical or theoretical point of view. Instead, it borrows facts from history, theory, and technology to illustrate the issue and question the possibilities.

To be a true comprehensive scientific article in any of the disciplines mentioned above, and to tackle such issues in depth it would take a lot more than one article. This text is a speculative projection and an invitation to think about/question the possibility of using robots—robot arms, beyond our biased readings of them as tools, order-takers, and service providers.

Well, robots—more or less, live outside of digital screens! That itself is interesting enough to think about them as possibly post-screen “beings”; but can robots become a medium for experience and perhaps design? Are they—different from digital screens discussed in the previous article, capable of becoming a host for an experience instead of just being communicators? Are they digital, analogue, or mixed/hybridized? Are they smart or dumb? Strong or weak? Provider or provided? Creator or creature? Although some of these questions are intentional false binary/bipolar comparisons, these and many others are part of my daily conversations and thoughts.

In this article and the following ones—in Post-screen column, we will mostly talk about industrial robot arms and frequently their recent generations. They are beings that “think” “digitally” with a computerized brain and act/perform physically and have always seemed to be used as translators of “digitally” curated commands. Beings who receive “digital,” hydraulic or mechanical information—commands in the form of position, orientation, motion, etc. and follow the “master’s order.”

This is more or less the core of how industrial robot arms generally operated—and still operate, from their initial integration in the daily life of “society,” as part of an industrial assembly line. In early 1960s, the inventor George Devol, together with Joseph Engelberger—“the father of robotics,” created the world's first robot manufacturing company, Unimation, and the first “industrial” robot arm Unimate. Unimation was closely working with the automotive industry. Unimate—first industrial robot arm, undertook the dangerous tasks of workers, by precisely taking “orders” and performing three shifts a day, 24/7 and invulnerably with “super-human” power.

However, it is arguable that this mindset—robots as superhuman workers, has been developed based on older biased social perspectives about labor, as some “one” that follows the order and serves an operation. Back in the days, robots and maybe in a bigger picture, machines—similar to human slaves/workers, were supposed to perform based on commands to operate a specific task. Assembling parts, harvesting, welding, painting, cutting, sanding, and carrying—to name a few, are all based on precise commands from the master and robot/machine functions as an operator. Arguably, if in some positions machines/robots replaced human workers, it was/is partially because they can follow orders “better.”

Unimate—first industrial robot arm, undertook the dangerous tasks of workers, by precisely taking “orders” and performing three shifts a day, 24/7 and invulnerably with “super-human” power.

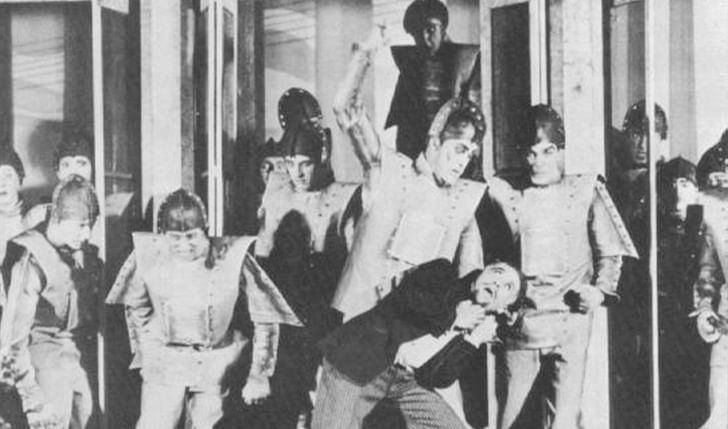

This interpretation probably gets tied back into an earlier reading of workers/labors, and machines/robots as coexisting beings in a same social/professional class. There is no surprise that through this lens and in science fictional speculations—where the technical and financial limitations are blurred into the radical possibilities of imagination, in the hands of authors such as Karel Čapek, robots become social revolutionists or rebellious creatures that take their social “revenge” through getting out of “control” and “thinking.” The term “robot” introduced to English language through Czech writer Karel Čapek’s 1920 science fiction play R.U.R (Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti). This play can be seen as probably the way from which robots (roboti) were seen/understood.

In his play (R.U.R), robotis are more or less, superhuman creatures, with some “thinking” abilities where these abilities result in the extinction of the human race, led by a robot rebellion. Later in his 1936 science fictional novel, War with the Newts, Čapek illustrates the idea of non-human servitude, even more clearly, where they become a servant class in the human society. In summary, robots are “good” if they follow orders and serve the human society as labors, otherwise they will be/are dangerous and will kill us!

Let’s fast-forward to almost 100 years later, to the world in which we currently live: Almost everything has changed. The conversation about equal rights in the society is blossoming more than ever. Even more fundamentally, some contemporary philosophical thoughts are calling for post-human perspectives through non-hierarchical/flattened ontological reads of beings, where every“thing”—despite their differences, “equally exist yet …not exist equally”[i]. The ideas of hybridization, interdisciplinary and collaboration are saturating our worlds and days continuously, and… robots—robot arms, started to become more integrated into diverse sets of operations.

In summary, robots are “good” if they follow orders and serve the human society as labors, otherwise they will be/are dangerous and will kill us!

The question, however, is precisely about this integration in creative set-ups. How can this integration be different from the older readings of robots as service providers and more as active agents in the creative process? How can the current social/philosophical climate of non-hierarchical relationships, help to open-up possibilities for “misusing” robots in a more collaborative way? How imperfections of a robotic operation can become a driver for a creative application? Can—in an experimental setting, the “mistakes” of a robotic task become more desired than the programmed task? How can robots as physically performing beings, become a post-screen medium with some level of creative agency?

Theses question are more than just the question of application; whether the robot has a car body in its hand or a painting brush of an artist or a fabrication end-effector. It is about its role in/impact on defining/guiding these processes through its—robot’s, “reading” of the process. It is about recalibrating our—“master’s” vision about welcoming a possibly new active agent in the creative process in a less biased hierarchy where the imperfection of a robotic operation is a not a “mistake,” instead is a “creative” suggestion from one of the active agents in the process.

To be continued…

[i] Ian Bogost, Alien Phenomenology, or What it’s like to be a Thing (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), 11.

Ebrahim Poustinchi, architect, artist, and inventor, is an Associate Professor of Digital Design at Kent State University. He has previously taught at the University of Kentucky, Washington State University, and UCLA. Poustinchi’s research is focused on the intersection of media and ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.