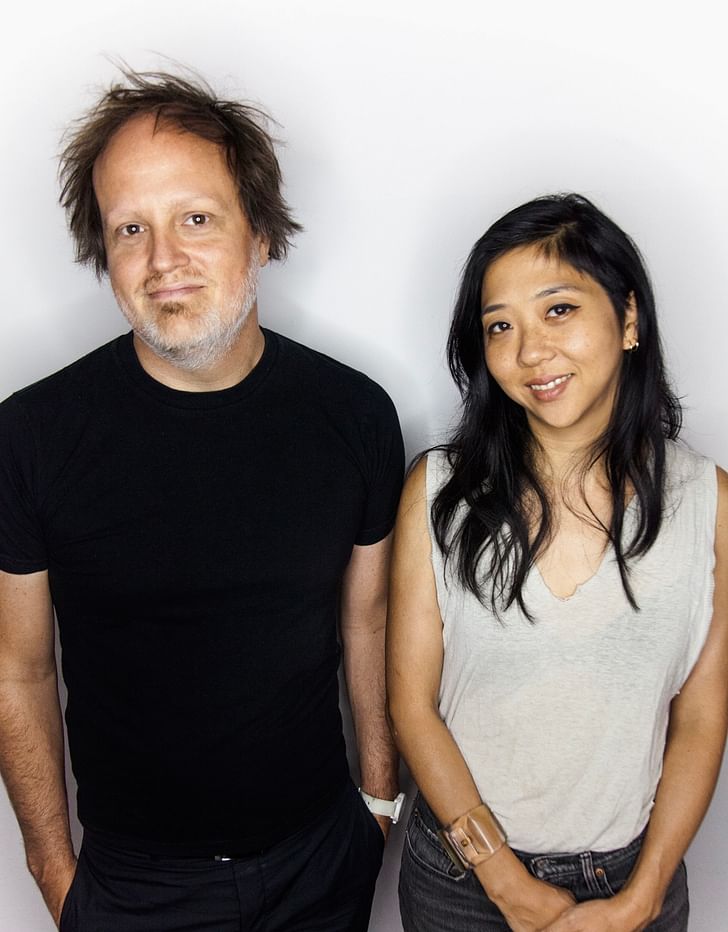

Based out of New York City and Houston, Rosalyne Shieh and Troy Schaum of the practice SCHAUM/SHIEH discuss the power of learning from cities through their complexities. Over the years, both have taken their interests in urbanism to look at the scale of individual buildings and the role they play in the larger built environment. As architects and educators, the two view their firm—and its projects—as the reflection of both a social unit and a cultural endeavor; all while still being a professional body of service.

For this week's Studio Snapshot, the duo talks with Archinect about the importance of identifying their values as a small practice and using collaboration to make room for each person to evolve. Focusing time and energy on the power of revision, SCHAUM/SHIEH reflects on the strength of their processes and how it translates to their work.

How many people are in your practice?

Five

Why were you originally motivated to start your own practice?

We wanted independence, we wanted to build, and we wanted to test out our ideas in a larger territory outside the academy.

Is scaling up a goal or would you like to maintain the size of your practice?

To a degree yes, we are interested in scaling up. The autonomy of the individuals in the practice, how each person is getting what they need, and the importance of the relationships between us—these are as important as the potentials of increased capacity and capabilities of a larger practice. For us, the practice is both a social unit and a cultural endeavor, as well as a body that offers professional services. So, for us it is an open question under constant revision about how to grow, how much to grow, and what is ideal. We would like to grow in a way that allows us to maintain the things about smallness that we value.

For us, the practice is both a social unit and a cultural endeavor

What are the benefits of having your own practice? And staying small?

Staying small means things stay personal. We have to collaborate as well as make room for each person to evolve over time. We maintain these values in face of the many dehumanizing pressures of the systems and times within which we live.

Do you have a favorite project?—completed or in progress.

Currently we are fortunate to be between the afterglow finishing Transart and starting up construction on a house in Lexington, Virginia that will be a private residence in the near term, and with a projected future as a playwrights' retreat. The hybrid program as well as the curiosity and openness of our clients has made the design process especially exciting, so we are really looking forward to realizing it.

Can you talk about Transart? What motivated you to come up with the form of the building and where did you pull your influences?

At Transart, we were playing material against form—a panel is a conceptual thing rather than a physically independent unit, like a ceramic tile or a sheet of plywood. The project resists categorization: as a house in which the owner can exhibit art and host conversations—events in which she invites in a larger public—the project functionally blurs the line between domestic and institutional. By extension, we were interested in the blurring between residential and institutional typologies, by playing with the massing, scale, and lines of the project. Specifically, in the carving of the mass into parts, we aimed to make the modest, residentially scaled mass to appear and feel larger than it was, and for the stucco walls to feel both substantial and light.

Many of your projects play on the design's interaction with the city it's located in. Being based in Houston and New York, how do these cities influence you?

As a city, New York has density, diversity, an extensive public transport system, a high concentration of arts, and a strong sense of identity. To reference Jane Jacobs, it’s full of strangers in close proximity—this gives it a special energy and openness. The design community thrives on the deep and broad social and intellectual culture. We enjoy the conversations and energy around the range of design problems being addressed in different areas of the city. Houston is another great paradigmatic city in the US; it is postindustrial, megalopolitan, and represents a stark alternative to New York. In Houston, the post-war paradigms of dispersion and the absence of zoning have been hugely influential in understanding the other cities we’ve worked in and been inspired by: Kaohsiung, Detroit, Venice, and Marfa.

Speaking of city influences, your practice heavily focuses on urban design projects whether they be actual or speculative. How have your works in Houston, Taiwan, Detroit, and Venice influenced your take on urban planning on a global scale?

The city is a complex object, one that is as much a set of processes and interrelations as it is a set of physical parts.

In the contexts that we’ve looked at, we have been interested in the city at the scale of the individual building—that is, what effects can be produced on a larger scale with a relatively small intervention. However, it is important to realize that many things are at play. The city is a complex object, one that is as much a set of processes and interrelations as it is a set of physical parts. On a global scale the most important things aren’t how buildings look and they are definitely not limited to spatial concerns; rather, access to clean water and the provision of healthy and fulfilling lives for animals, people, and environments are paramount. As far as how the project of the city might contribute to this, we often come back to Jane Jacobs’ invocation of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. at the beginning of Death and Life of Great American Cities:

…the chief worth of civilization is just that it makes the means of living more complex; that it calls for great and combined intellectual efforts, instead of simple, uncoordinated ones, in order that the crowd may be fed and clothed and housed and moved from place to place. Because more complex and intense intellectual efforts mean a fuller and richer life. They mean more life. Life is an end in itself, and the only question as to whether it is worth living is whether you have enough of it.

If you could describe your practice in three words what would they be?

Laugh. Revise. Surprise.

Katherine is an LA-based writer and editor. She was Archinect's former Editorial Manager and Advertising Manager from 2018 – January 2024. During her time at Archinect, she's conducted and written 100+ interviews and specialty features with architects, designers, academics, and industry ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.