We are never so aware of architecture as when it breaks down. Our lives require that buildings slip into the background, that we can trust their promise to shelter. But when the ground trembles, when cracks appear in the walls, and the foundation itself shakes, suddenly the frailty of this promise emerges in stark relief. An earthquake is the black mirror to architecture: the memento mori of its claim to firmitas.

For centuries, humans have learned to live with the uncertainty of earthquakes. Cities prone to tectonic instability have developed strategies to adapt, with varying degrees of success. In recent years, our skills have certainly improved. And yet, it is unlikely we will ever be completely immune to their danger. Looming in the imaginaries of urban residents from Tokyo to Los Angeles remain the haunting specter of the “Big One,” earthquakes capable of splitting not just concrete but also land itself. And, as we become more dependent on technologies like nuclear power plants and massive dams, their potential for cataclysmic damage grows. We depend upon an intricate web of infrastructure more fragile than it appears. What’s more, much of this infrastructure not only increases the severity of ramifications, but also the severity of a quake itself, with new studies indicating that recent technological developments like fracking can serve as triggers for tectonic events.

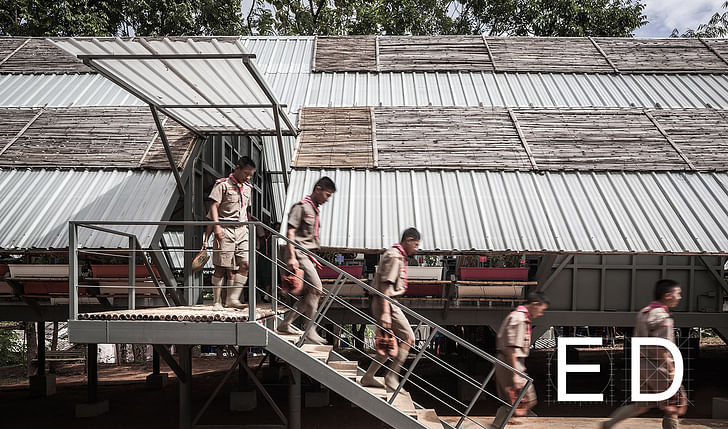

In short, architecture is always in a dance macabre with the threat of an earthquake. We spoke with Vin Varavarn Architects from Thailand, to learn about their strategies to mitigate such disasters.

How old is your practice?

Twelve years old.

How many people are in it?

Ten people including myself: eight architects, two interior designers, and one administrator.

What would you describe as your office’s ethos or guiding principle?

For us, our architecture is always oriented around the human being and a sense of realism. We believe architecture should communicate and link with those with different perspectives—both directly and indirectly, in reality and in abstraction. Architecture does not constitute purely a design of a building, but the aim is also to create interesting and meaningful experiences.

Architecture is always oriented around the human being

What was the impetus for the earthquake-resistant school project? Did the client approach you?

After the strong earthquake in Chiang Rai destroyed seventy-three schools, affecting over two thousand students, we were contacted by a non-profit network in Thailand called Design for Disaster (D4D), who asked us to participate with the Pordee Pordee Classroom program. The program invited nine Thai architects to design nine new post-earthquake schools in the most affected school areas.

What was the brief for the project?

Our assigned school is Huay Sarn Yaw Witthaya School. The school is an Extension Opportunity Secondary School, which accepts student who are unable to enter the district schools. All the students come from poor, hill tribe families and many of them have some form of a learning disability.

The school needed the building to have three new secondary classrooms to replace the previous building which was destroyed by the earthquake. The design requirements specified that the new classroom building must be earthquake-resistant, easily constructed by local workers, and as low budget as possible. Most of the selected building materials had to be lightweight to reduce horizontal momentum caused by the weight of the building during an earthquake.

The school director also wanted to see the new building integrate and harmonize with the surrounding natural environment.

Why did you have to make the building earthquake-resistant? What was involved in this process?

It is part of the brief because there is a possibility that a strong earthquake might occur again in the future. While other existing school buildings were not designed to withstand the earthquake, these new schools can ensure that students will have a safe haven during and after the earthquake.

In the long term, it is intended to benefit the people in the community as widely as possible.

At the outset of the project, we did not have any budget available for construction, so we decided that the structural elements should be designed to be exposed to reduce unnecessary costs. In addition, the building was designed to serve as a learning tool for the students and local people to learn about earthquake-proof building, which they had never seen before. The proposed school building should also become a prototype that can easily be developed, modified, or adapted to other types of building typologies, such as houses, pavilions, libraries, etc. So, in the long term, it is intended to benefit the people in the community as widely as possible.

We worked closely with our structural engineer with the consultation of the Engineering Institute of Thailand. And during the construction period, we also had the support of the Consulting Engineers Association of Thailand and Thai Contractors Association to ensure the quality of the construction work throughout the process.

How do you perceive the relationship between architecture and natural disasters?

Architecture has always related to human beings, environment, and society, both directly and indirectly. It can create both good and bad examples with long term consequences.

Today, our world and our environment continuously undergo changes. This situation has immensely affected our lives. It is our responsibility as an architect to create innovative architecture which can respond to this dynamism.

To find out more about the project, get your hands on a copy of Ed #2 The Architecture of Disaster here!

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.