In March of 2014, United States Customs and Border Protection awarded Elbit Systems of America a contract to design, construct, and deploy Integrated Fixed Towers (IFT) at an unspecified number of sites in unspecified locations along the southwestern border of the United States. Elbit’s responsibilities extended beyond mere construction and monitoring to in situ testing, ensuring customer satisfaction with their product’s ability “to detect, track, identify, and classify movement on the border” [1].

While sites and numbers remained obscure, the objective of the towers was certainly made clear: they were to be integral nodes in what was becoming an increasingly robust border surveillance apparatus. Supporting agents in the field with “long-range, 360-degree, all-weather, and persistent surveillance capabilities,” the towers would assist CBP in “identifying and classifying ‘items of interest’” near the border [2]. Moreover, the towers were touted as a “ technology solution for the distinct terrain within USBP Tucson Sector.”

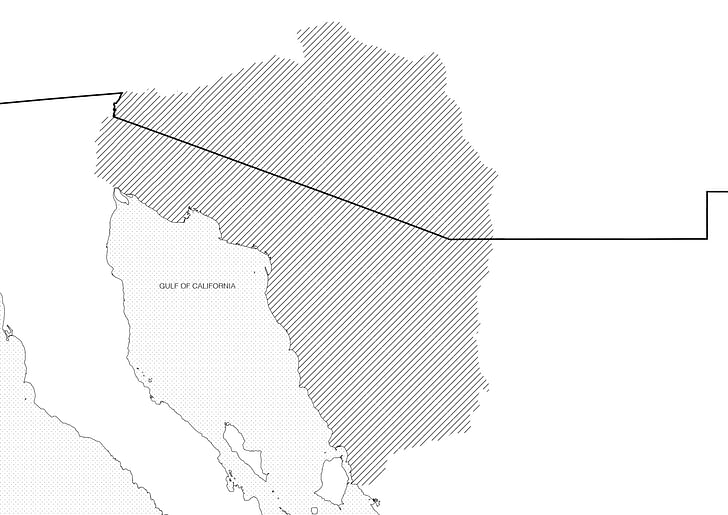

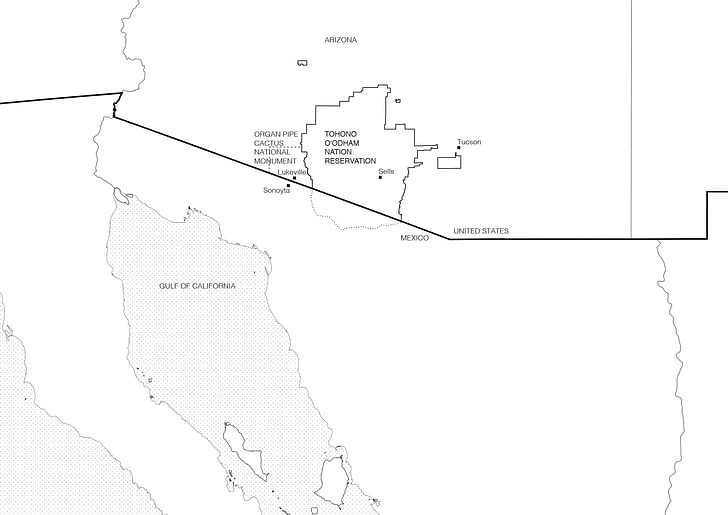

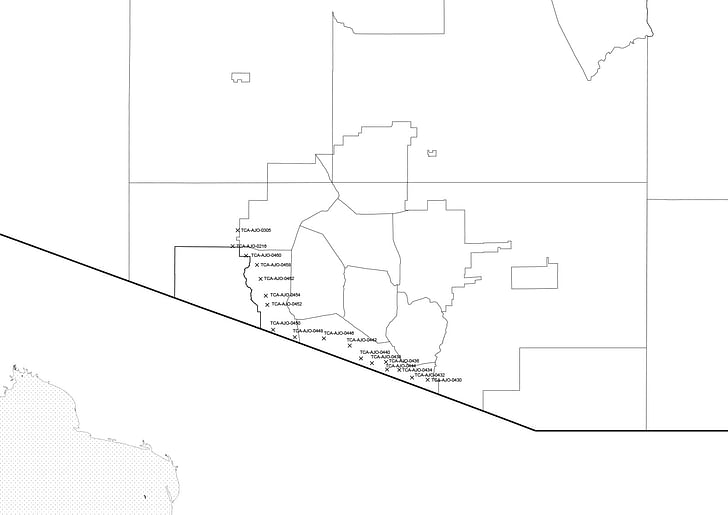

The Sonoran Desert terrain of the United States Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector is indeed distinct, but where CBP ended up proposing to build the IFTs was in an even more specific swath of this arid landscape. Barring any changes in federal border policy or a major intervention on the part of tribal government, sixteen Integrated Fixed Surveillance Towers will be erected in the Tohono O’odham Nation along its southern border with Mexico and its western border with the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, which extends far into the interior of the United States.

The Tohono O’odham traditional lands encompass thousands of square miles of Sonoran Desert in a territory that straddles what is now the border between Arizona in the United States and Sonora, Mexico. Historically, tribal members have moved fluidly through this terrain, traveling to seasonal villages, harvesting saguaro cactus, visiting the Gulf of California, and performing spiritual walks or runs. Yet today, the Nation represents only a tenth of the territory the O’odham inhabited for centuries—a territory systematically reduced through invasion, land purchases, and executive orders that the O’odham—never recognized as a sovereign nation by the United States or Mexico —were not party too. On what was until 1917 O’odham land, there is now a United States National Park, a United States Air Force Base, and a United States border. In short, the United States federal government, in one form or another, exercises jurisdiction over ninety one percent of O’odham ancestral lands—lands once understood solely through O’odham traditional knowledge and inhabited through O’odham sovereignty.

Despite the constriction of their landbase, crossing the international border has remained a daily activity for the O’odham, necessary in order to practice their religion and traditional way of life, visit family (many of the tribal members have family on both sides), collect traditional food, receive healthcare and education, and partake in a cross-border economy. For this reason, the O’odham Nation’s constitution determines tribal membership on the basis of a person’s ancestry and not a person’s citizenship. That means someone with sufficient O’odham blood born in Mexico is a member of the tribe—a tribe recognized by the United States government. But post-9/11 Patriot Act legislation has changed this historically open terrain and restricted the mobility of its inhabitants. With the Patriot Act, crossing the US-Mexico border along the Tohono O’odham nation was restricted to three “tribal gates”—Customs and Border Patrol managed checkpoints, where sufficient documentation is needed to cross. Crossing along traditional, unguarded paths was made illegal. This has produced an incredibly complex and increasingly tight condition of border militarization, where divergent understandings of property, connectivity, and permanence have created an impasse in which indigenous rights to the land are seen as incompatible with the perceived demands of national security.

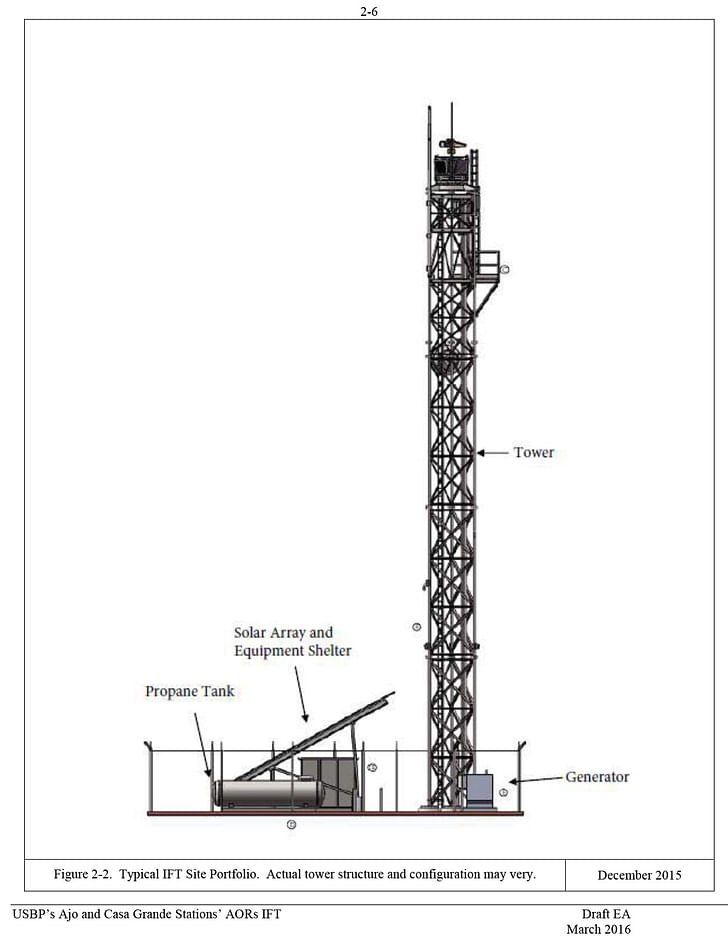

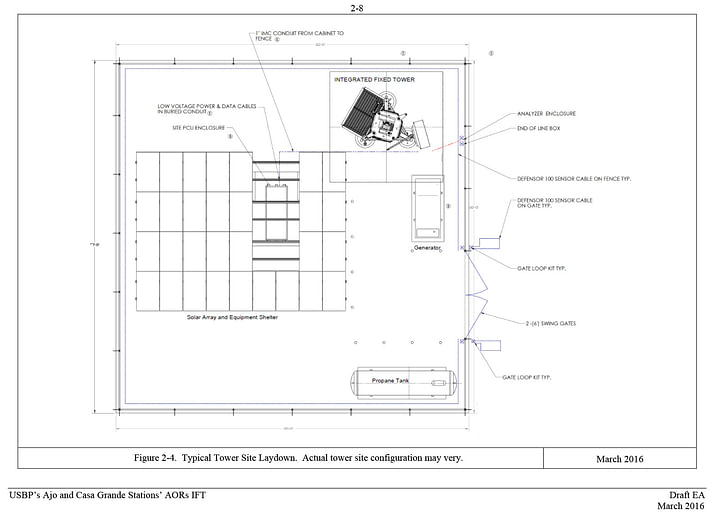

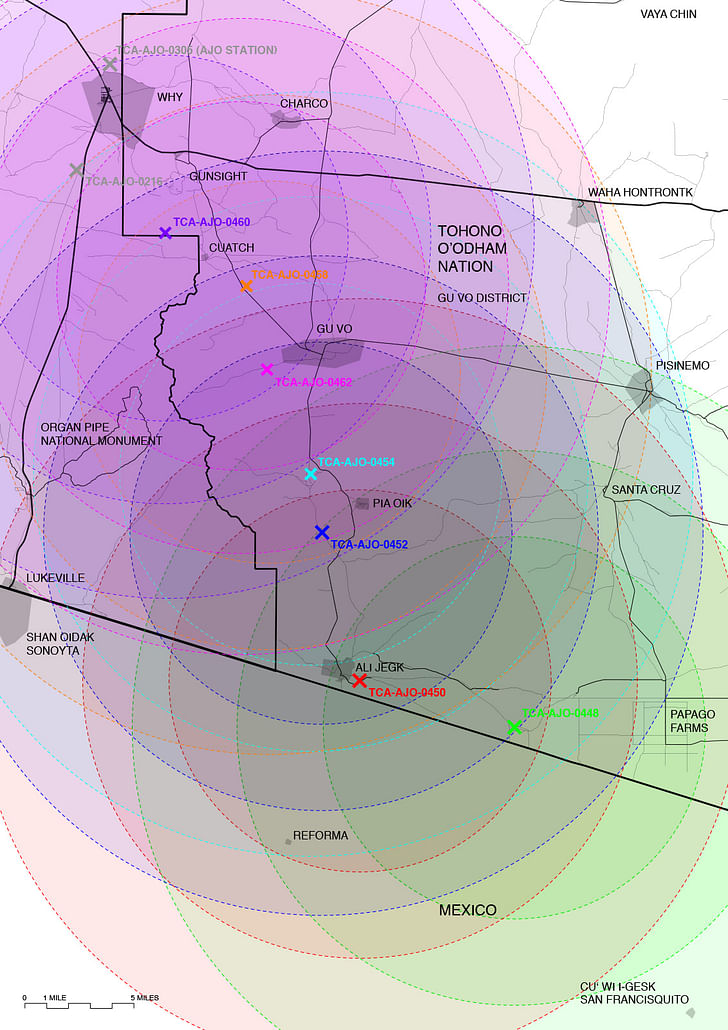

The proposed IFTs would be laid out in a curved line following the US-Mexico border before turning at its juncture with the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and extending along the Tohono O’odham border into the interior of the United States. Structurally, these towers are pretty straightforward. 120 to 180 feet high, they include a base with a propane tank, generator, solar panels, and equipment shelter. Their footprint is anywhere from 50 by 50 to 160 by 160 feet wide and includes a parking area. They are surrounded by a fence that would enclose up to 10,000 square feet, and a 30-foot wide fire buffer beyond that. Tower access will also include seventy miles of new road, including entirely new access roads, the widening of existing roadways, and drainage ditches. They are then hooked up to the grid where possible, necessitating new power lines and fiber optic cables [3.

But the footprint of the towers extends beyond the perimeter of the fence, and even beyond the roadways that connect to it. They will be equipped with a range of surveillance equipment designed to, again, identify and classify “items of interest” near the border. This includes radio-frequency radar that can detect moving bodies within a 9.3-mile radius, long-range video cameras to capture everything within a range of 13.5 miles, another radio-frequency radar that can detect moving vehicles within an 18.6-mile radius, and microwave communication receivers that transmit up to 40 miles. In addition to that they hold spotlights and laser illuminators for night operations.

What radar, cameras, and lights are able to capture, communication systems and dirt roads facilitate the pursuit of. Strategically flanking the Sierra de Santa Rosa and the Ajo Range (Tak-Va’Vak in O’odham) that divide park from reservation, the towers rely on the region’s geography for maximal surveillance and visibility. Visibility is essential not just as a vantage point over land but also as a line of sight. In order for microwaves to reach from one tower to the next, each must be aligned in an unobstructed path. For comprehensive video and radar feeds, the radii of their range must overlap. And they do so extensively, reaching beyond the US-Mexico border into Tohono O’odham traditional lands in Mexico.

It’s no coincidence that along with the construction of towers comes detention facilities for people apprehended crossing the border. It also requires little stretch of the imagination to understand that the infrastructure apparently needed to support construction and maintenance of towers (the truck paths latticing the desert, the movement of Border Patrol Officers to nearby stations, the tracts of housing and trailers of mobile offices) are also quite useful in the pursuit of “items of interest”—be those local residents, US citizens, or migrants entering the country legally or illegally—and the persistent, low grade harassment of permanent population in the borderlands.

Site surveying has begun to have an impact on the land and daily life in a place already transformed by border militarization. There are approximately 1,500 customs and border patrol agents stationed in the three sectors that have jurisdiction over the reservation. The population on the reservation is about 16,000. That’s one border patrol agent for every ten O’odham. While not all of these 1,500 agents are on duty at the same time or on duty on the reservation (the Ajo sector, Casa Grande sector, and Tucson sector include other areas as well), it does give you a sense of how saturated the region is by law enforcement. This is what is meant by “persistent surveillance,” the term CBP uses to describe the capability of the towers.

Given the Department of Homeland Security’s increased funding, these numbers are liable only to increase. These towers are a great incursion on the sovereignty of the O’odham—the most recent in a chain of systemic rights violations that date back centuries. Not only do the towers’ impact extend much beyond their physical footprint, the area of their right of way—a considerable 6,428 acres—and the border patrol they bring with them are just one more instance in a very long history of the United States government militarizing and occupying Native American land.

An infrastructure of surveillance—which includes patrolling bodies—and its attendant culture of fear has changed a tribal relationship to the land with significant cultural consequences. The towers, like the border fence, become agents of indoctrination, material mechanisms used to assimilate tribal members into Western culture, with divisive consequences. The increased presence of Border Patrol Agents, for instance, has caused young O’odham to spend more and more time at home instead of out on the land.

By claiming the tribal ‘common’ land of the reservation as the space of surveillance and militarization—as property of the federal government and within its sovereign territory—border patrol forces tribal members into a space that they can easily define as private property of their own: the house [4]. By pushing tribal members into a lifestyle centered around private property, border surveillance not only has immediate consequences in terms of physical and psychological well-being (obesity, for instance, is a big problem on the reservation and harassment has already been normalized among the youth), it also ruptures intergenerational ties and spiritual knowledge and results in cultural disconnection to the land for its inhabitants. As tribal elder Ophelia Rivas says, “Land has always been defined by Europeans as properties. [CBP] have a different perspective on land and so from that perspective it’s very difficult for them to understand our relationship to it. I’m saying that because I’ve seen the reaction of the border patrol when we talk about our land and how we’re connected to it. It seems not to make a difference to them that it’s of great concern to us. It’s very disturbing to the people who continue to follow that ceremony way of life. […] When I grew up I climbed all these mountains and we ran and played all over. There were also people crossing the border that were undocumented. There was always drug trafficking, but we played everywhere. And now the kids are just stuck in their homes. It seemed it changed our whole way of life. It impacted it ever since this constant surveillance began. And when it began after 9/11, it was so aggressive that it forced the people not to go out on the land anymore. And that is really affecting the health of everybody. The health of the elders—which really need to be out on the land to connect with the plants and with the mountain. From that point on the children don’t see their elders out there, they’re not connecting to that part of our life. This forced disconnection to the land is unhealthy because with the disconnection they lose their language, traditional diet, and sensitivity to turn to traditional medicine” [5].

In April 2017, CBP published an Environmental Assessment, as final step of the National Environmental Policy Act process they followed, stating that Integrated Fixed Tower project will have no considerable impacts on the ecosystem or the tribe [6]. As the widespread opposition to these towers by many tribal members and several traditional leaders shows, this is not the case [7]. Because of their strong connection to the land, a connection border militarization is already eroding, residents of the tribal districts affected by the towers feel the towers’ presence would be catastrophically disruptive to spiritual practices and daily life, as well as irreversibly destructive to a landscape they hold as sacred.

The Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument is a 517 square mile swath of National Wilderness to the west of the Nation. Because of the park’s preservation mandate, it is mostly empty of human life. No one lives there except a few rangers, only a couple roadways crisscross its plateaus and plains, and, in order to facilitate migratory paths, no barriers were permitted along the border until 2004. As CBP was tightening its grasp on border city bottlenecks in Nogales and Yuma in accordance with the Southwest Border Strategy, migrants were funneled toward the park where they would often cross its eastern border and enter the Nation seeking food and assistance. So, in the 1990s, US Border policy and preservation practices colluded to create the “high risk” situation in the Nation that today necessitates a “persistent surveillance” infrastructure. In 2003, the situation was amplified when the park was closed following the 2002 shooting of one of its rangers and the very Wild West declaration of it as the “most dangerous national park" [8]. During Organ Pipe’s closure from 2003 to 2014, CBP built a vehicle barrier along the entire extent of the international boundary within the park, and erected several mobile surveillance towers near the international boundary as well as at the very northern edge of the park along its border with the Tohono O’odham Nation. In 2014, when the park reopened, CBP proposed the sixteen towers in the Nation, including eight along the border with Organ Pipe Cactus Monument (not Mexico) connecting to the mobile towers already installed in the park.

In a recent interview, superintendent Ranger Brent Range touted the close and collaborative working relationship the park has with the Department of Homeland Security. It’s a relationship that was undoubtedly enriched through a decade of collaboration over border infrastructure, but that also predated the closure of the park. As Rick Felger, Director of Natural Resources, told us, the park works closely with the border patrol when agents find ‘cultural artifacts’—which is to say, O’odham artifacts as the park used to be O’odham land—and are required by the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) to consult with the Organ Pipe archeologist and the National Park Service’s regional conservation center in Tucson. The National Historic Preservation Act—the law that governs how park rangers handle the human and cultural remains they find—is also what is invoked in the Environmental Assessment, which was commissioned by CBP as part of the standard approval procedures for large-scale infrastructural projects.

Neither the preservation framework, regulated by the National Park Service, nor the Assessment take into account the deep and myriad ways that the construction and presence of the towers would harm daily and spiritual life of nearby residents. According to O’odham beliefs, ceremonial pottery and human remains should not leave their place of entombment. They are just as much a part of the mountain as the caves, the cactus, the grasses, and the grazing deer. Uprooting them at all is extremely offensive—let alone expatriating them to a conservation center in Tucson where the tribe must petition to have them returned. Road clearing and surveying has already uncovered countless pieces of pottery and of bodies. It has also stunted the growth of mountain grasses and displaced deer, tortoises, sheep, and jaguars from their migration routes and habitats, impacting the O’odham hunting rituals that are integral part of the O’odham traditional calendar. The widespread reach of these concerns and their ecological and cultural interconnectedness doesn’t register with the Department of Homeland Security, whose property-based conceptual framework they fall outside of.

Archeological investigations needed to produce an Environmental Assessment and determine worthiness of historical preservation impose a Western scientific frameworks onto O’odham way of life, and fail to understand that O’odham himdag (way of life) and history cannot be isolated in precise coordinates or confined in 250-foot investigation radii. Instead of thinking about proposed tower sites as specific points on a map potentially requiring federally-adjudicated National Historic Preservation, a true environmental assessment ought to think about how the environment as a whole will be impacted by tower construction and persistent surveillance—from the penetration of microwaves to the unpredictable patterns of border patrol vehicles. The violence of these towers will be at once immediate and apparent as well as passive and invisible. Emissions from towers will affect the presence of living beings for hundreds of square miles—and, bringing Jeremy Bentham to the twenty-first century, local communities will potentially always be under watch.

The NHPA, and the legal framework that produced it, does not recognize a holistic approach to preservation, instead favoring specific sites and built structures for protection. What’s more, the Act assumes an American nationality rooted in a colonialist historical narrative instead of a pluralistic national or transnational identity. These sites are in the Tohono O’odham Nation, and their need for preservation should be evaluated according to their significance for that Nation and in a way respectful to tribal culture.

Environmental Assessments or Impact Statements are ubiquitous in architecture and planning, yet their format goes uninterrogated: their inherent biases are accepted as necessary for many construction projects, establishing default definitions for ‘environment’ or ‘impact’ without questioning how those words change among sites and contexts. But, as the conditions here and recent struggles at Standing Rock show, these perceived forms can perpetuate epistemological violence and a hegemony of expertise.

What the nature of opposition to the Integrated Fixed Towers on the Tohono O’odham Nation clearly shows is that the clamoring not to build goes hand in hand with the repudiation of the ideology that underpins the rationale for those projects’ necessity. In opposing the Department of Homeland Security’s Environmental Assessment, the O’odham do not offer alternative locations for the towers, or request fewer towers installed, as suggested in the Alternative Proposal the Assessment. They entirely refuse the premise that the towers are needed on the basis that the constellation of human, material, and ideological elements that comprise each tower infringe on indigenous sovereignty. The repudiation of the tower project forces us to reassess not only how we, as people who work with and think about the built environment, talk about impact, it also pushes us to question on what basis potential sites for large-scale built projects are assessed and impacts are negotiated and where the voice of the impacted community meets the experts assessing environments according to standardized categories and scientifically sound evaluation methods. In the case of the Environmental Assessment on the Integrated Fixed Tower project on the Tohono O’odham Nation, the numerous objections sent to the processing agency by tribal individuals and districts affected did neither change nor find entry into the final document. One aspect the tribe’s repudiation of the IFT project clearly does put into question is the distinction between action and inaction, preservation and resistance. At this point they can no longer be understood as opposed categories. The challenge now is for that opposition to prevail over the decisions of the Department of Homeland Security.

This article is coming out of an ongoing collaboration between the authors and Ophelia Rivas, a Tohono O’odham tribal elder and activist who has been vital to the research.

[1] “Integrated Fixed Tower,” International Towers Inc. website.

[2] “Elbit Systems of America Achieves Significant Milestones for the Nogales Integrated Fixed Towers System,” Elbit Systems website, September 10, 2015.

[3] See “Final Environmental Assessment For Integrated Fixed Towers On The Tohono O'odham Nation In The Ajo And Casa Grande Stations' Areas Of Responsibility U.S. Border Patrol Tucson Sector, Arizona U.S. Customs And Border Protection Department Of Homeland Security Washington D.C.” (April, 2017).

[4] For more on mobility, property, and liberalism see Hagar Kotef, Movement and the Ordering of Freedom: On Liberal Governances of Mobility (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

[5] Interview with Ophelia Rivas, December 13, 2016.

[6] Available here.

[7] For more on the Southwest Border Strategy see Office of National Drug Control Policty,“National Southwest Border Counter Narcotics Strategy." Also please see Department of Homeland Security,“Border Security in the 21st Century,” powerpoint. For a critical assessment of the effects of the Southwest Border Strategy on the O’odham Nation see Kenneth D. Madsen, “Local Impacts of the Balloon Effect of Border Law Enforcement,” Geopolitics vol. 12, no. 2: 280-298.

[8] Tim Gaynor, “Arizona Border Park Once Deemed ‘Most Dangerous’ in US Reopens to Public,” Al Jazeera (April 23, 2015).

I'm a writer, editor, and architectural historian, I am also a founding partner and the director of communications at Finishing Agency. As a historian, I look at issues of territory, sovereignty, and infrastructure building across the Americas. At Finishing, I bring ideas to life through ...

Nina Valerie Kolowratnik is an architect and researcher based in Vienna and New York. Her practice is situated in the context of forced migration and claims to land and property, and develops spatial notational systems that operate within legal and human rights debates. Since 2014 she has ...

1 Comment

Thank you for reporting on this.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.