Fellow Fellows is a series that focuses on the current eruption and trend of fellowships in academia today. These positions within the academic realm produce a fantastic blend of practice, research and design influence and traditionally within a tight time frame. Fellow Fellows sits down with these fellows and attempts to understand what these positions offer to both themselves and the discipline at large. Fellow Fellows is about bringing attention and inquiry to an otherwise maddening pace of refreshed academics while giving a broad view of the exceptional and breakthrough work being done in-between the newly minted graduate and the licensed associate.

This week we talk to Zachary Tate Porter. He is a historian, educator, and designer based in Los Angeles. He uses objects, images, and texts to explore the shifting conceptions of ground that undergird architectural production. Zachary Tate Porter was the 2015-2016 Design of Theory Fellow at SCI-Arc.

The conversation, focus and applications to fellowships in general has exploded over the past decade. They have become the go to means of exposure, legitimization within the academia and in some respect the HOV lane of historically PhD owned territories of research and publication. What are your views of the current standing of fellowships as a vehicle of conceptual exploration?

I think the energy and excitement generated by recent fellowships is quite productive for the discipline at large. However, I don’t necessarily consider this form of speculative research to be in direct competition with traditional scholarship. In other words, I don’t see the fellowship as a replacement for the PhD. As someone who has done both, I found them to be radically different endeavors with their own unique sets of objectives, responsibilities, and criteria for evaluation. Perhaps the most significant difference is the time-scales on which they operate. Since a one-year fellowship lasts only a fraction of the time spent pursuing a PhD, the fellowship research must progress at a much higher rate of speed. There is also an expectation that fellowship research should engage the design community at the host institution, whereas PhD research has the luxury and freedom to operate completely independent of contemporary discourse. In this sense, one might envision fellowships as a critical linkage between design practice and traditional scholarship in architectural history and theory.

What fellowship were you in and what brought you to that fellowship?

I was the 2015-2016 Design of Theory Fellow at SCI-Arc. This is a fellowship that SCI-Arc has now transitioned into a post-professional degree in “Design Theory and Pedagogy.” I was initially drawn to this specific fellowship because of its emphasis on bridging the divide between design and theory–a division that I’ve always regarded as artificial and unnecessary.

Since a one-year fellowship lasts only a fraction of the time spent pursuing a PhD, the fellowship research must progress at a much higher rate of speed

What was the focus of the fellowship research?

My research during the fellowship year focused on the shifting conceptions of ground that undergird architectural production. I was particularly interested in reconsidering ground in the aftermath of post-structuralism, which effectively negated the role of ground as a foundational structure for architectural thought. From my perspective, the contemporary responses to these post-structuralist critiques have oscillated between two equally flawed extremes. Some architects choose to disregard ground altogether, embracing instead the autonomy of objects. Conversely, other architects intentionally seek to dissolve buildings into ground, thereby blurring the traditional distinction between architecture and landscape design. So, my research was aimed at developing a discourse on ground that would open up new intellectual territory between these extremes.

What did you produce? Teach? And or exhibit during that time?

During the fellowship, I taught an undergraduate design studio, as well as a seminar on my research, entitled “Theories of Ground.” The seminar was a lot of fun, because we were able to really dive into all sorts of theoretical and historical discussions of ground and then project some of those ideas back onto contemporary design practice. Aside from teaching, I also edited SCI-Arc’s journal, Offramp, which was an opportunity to curate a wider conversation on ground. The issue that I edited brings together a diverse range of architects, historians, and theoreticians, each of whom tackles the question of ground from a slightly different perspective. For instance, the issue contains design speculations by Jennifer Bonner and Neyran Turan, a historical (and poetic) essay on the Farnsworth House by Nora Wendl, as well as an interview I did with Tom Wiscombe, among many other contributions. The final culmination of the fellowship was a public lecture that I delivered at SCI-Arc in November 2016. For me, this lecture, titled “Cuts and Fills: Constructing a Discourse on Ground,” was a way to reflect on the interrelations between the teaching, research, and design speculations that I undertook during the fellowship year. In this sense, the lecture demonstrated the ways in which architectural design and history/theory can be productively interwoven.

How has the fellowship advanced or become a platform for your academic and professional career?

The Design of Theory fellowship at SCI-Arc certainly provided me with a platform to produce new research and share it with a wider audience. More specifically, it gave me the opportunity to edit a journal, teach a research seminar, and present a public lecture. But even beyond these formalized aspects, the fellowship brought me into contact with a whole new community of designers and intellectuals in Los Angeles. This immersion in the LA’s design culture was probably more important than the fellowship itself.

What negative sides to a fellowship do you see? (if any)

I don’t really see any negative aspects that would apply to fellowships generally. However, I will say that it can be intimidating for an emerging designer or scholar to enter a completely new context with the expectation of producing innovative research. There is a natural tendency to want the lay of the land before asserting one’s own voice. But there really isn’t time for that–so, you just have to jump into a conversation that started long before you arrived on the scene.

What is the pedagogical role of the fellowship and how does it find its way into the focus and vision of the institution that you worked with?

During my fellowship at SCI-Arc, I taught a core design studio, as well as and a seminar focused on my own research agenda. So, in my case, the seminar was where the fellowship allowed me to contribute to the pedagogical culture of the school.

the fellowships are a great way of fostering conversation between architectural communities across the country

Where do you see the role of the fellowship becoming in the future and how does it fit within the current discipline of architecture?

Generally speaking, the fellowships are a great way of fostering conversation between architectural communities across the country. You might have a recent graduate from a West Coast school doing a fellowship in the Midwest (or any other geographical combination), and all of the sudden there is an exchange of ideas and aesthetics. Of course, these kinds of exchanges are happening in the digital realm as well, on various blogs and social media platforms. But the fellowships make that interaction both more personal and more comprehensive than the vast array of images circulating on the web.

There is some criticism that a fellowship is a cost effective way for institutions to appropriate potent ideas while leaving the fellow with little compensation besides the year of residence and no guarantee of a permanent position? What is your position on this?

In my case, the compensation was fair and the terms were clear. Certainly, if you went into a fellowship with the expectation that it would automatically turn into a full-time position, then you might be disappointed. But it was nice fit for me at that time, because I was still in the process of finalizing my PhD dissertation.

What support, and or resources does a fellowship supply that would be hard to come by in any other position? Why would you pursue a fellowship instead of a full time position?

Given their short time spans, fellowships provide a research environment in which the risks are relatively low for both the researcher and the institution. For this reason, fellowship researchers are able to pursue topics that might be more speculative or radical than the established research projects of the host faculty.

What was your next step after the fellowship?

After the fellowship, I accepted a position within the School of Architecture at USC. I’ve been teaching there for the past two years.

What are you working on now and how is it tied to the work done during the fellowship?

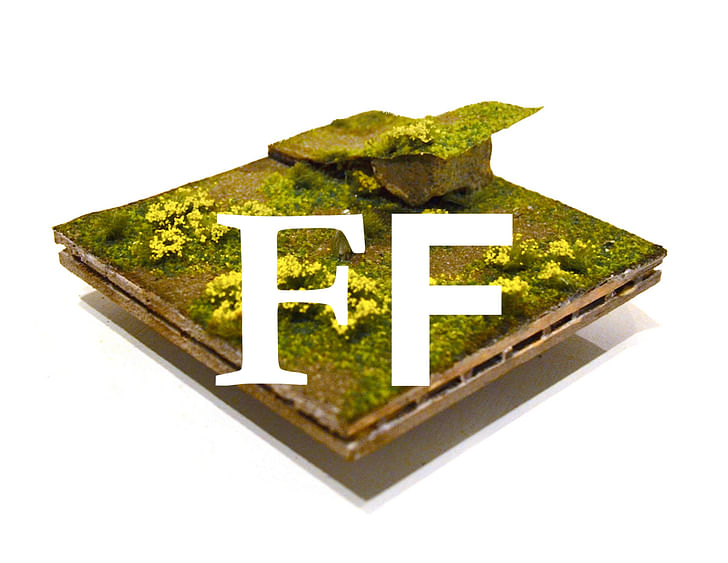

I certainly see my current work as an extension of the fellowship research. Both are aimed at tracing the conceptual and material manifestations of ground within modern and contemporary architectural production. Lately, I’ve been testing out more experimental and speculative methodologies for this work. For instance, I recently collaborated with a performance artist (Christina Novakov-Ritchey) and creative writer (Mari Beltran) to produce an installation that reframed the picturesque through conceptions of materiality and labor. I also developed a board game that reformats my doctoral research on interprofessional competition as an interactive and playable experience. Jurisdiction: The Board Game, which will be debuted at a public lecture performance in March 2018, allows players to choose a design discipline and then compete against allied professionals over various forms of ground (parks, streets, plazas, etc.). Alongside these research projects, I’ve continued to make objects and images as a means for refining my own conceptions of ground. Some of those artifacts were displayed at USC last November in my faculty exhibition, “Assorted Grounds.” I’m specifically interested in this multimodal approach to architectural research, because it allows me to work across multiples scales and temporalities. This multiplicity, in turn, facilitates feedback loops and connections among the various components of my larger research project. Ultimately, the ambition is that this cross-pollination of historiographic, theoretical, and design-oriented methodologies can both contribute to the emerging discourse on ground and help dismantle the traditional division between history/theory and design.

What advice would you have for prospective fellowship applicants?

I think my main piece of advice would be to really consider the limitations and opportunities of the one-year time frame. On the one hand, this short length means that the research proposal must be clearly defined and tightly constrained. On the other hand, it means that the research can be risky and provocative.

Anthony Morey is a Los Angeles based designer, curator, educator, and lecturer of experimental methods of art, design and architectural biases. Morey concentrates in the formulation and fostering of new modes of disciplinary engagement, public dissemination, and cultural cultivation. Morey is the ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.