“Where is Vermilion Sands? I suppose its spiritual home lies somewhere between Arizona and Ipanema Beach, but in recent years I have been delighted to see it popping up elsewhere — above all, in sections of the 3,000-mile-long linear city that stretches from Gibraltar to Glyfada Beach along the northern shores of the Mediterranean, and where each summer Europe lies on its back in the sun. That posture, of course, is the hallmark of Vermilion Sands and, I hope, of the future—not merely that no-one has to work, but that work is the ultimate play, and play the ultimate work.”

- J.G. Ballard, preface to Vermilion Sands, 1975

Since at least Vitruvius, 2000 years ago, the architecture of architecture has always been discourse. A discourse that produced the distinction between architecture as building or construction, and architecture as an art and culture of these activities. For this reason, the question of “the architecture of architecture” is actually that of how knowledge is culturally and geopolitically partitioned, and in whose service—a partition that ‘architecture’ sometimes pretends to do all by itself, for ‘itself.’ Modern and contemporary architects have often self-righteously misunderstood this as an inherently autopoetic potential—a capacity for self-making. But as Donna Haraway and others remind us, there is no auto-poiesis, only sym-poiesis: not self-becoming, but becoming-with. In other words, we (architects-humans-things) are not alone, have never been and never will be. In fact, the illusion of aloneness and its dialectical correlate, wholeness, is perhaps the modern world’s most impressive and delusional spectacle.

Architecture as art and culture is one of the ways in which we have navigated this illusion. In the critical theories of the last 200 years, the eclecticism of architecture’s forms—from doors and windows, primitive huts and painterly walls, various typologies and norms—has been criticized as the violent aloneness of the commodity form: alienated from its social relations and produced for the sake of market circulation, this eclecticism masks the fundamental logic that determines its appearance—capital accumulation on the basis of exploitation. On the other hand, together with this art and culture of architectural eclecticism there has been an enormous proliferation of variety for variety’s sake: the gaudy spectacle of modern change (aka capitalist ‘growth’), which is, however, much more homogenous than it appears.

The challenge for an architecture seeking its own architecture is to find ways of navigating this paradoxical ‘homogenous variety’ which is the hallmark of the modern. In other words, it is the challenge of figuring out what is real change, real difference, real growth, and not just repetitions of the same.

what is real change, real difference, real growth, and not just repetitions of the same

To achieve this, we need to re-open two issues that for too long have been mired by teleological assumptions: architecture’s relation to time and knowledge. More than metaphysical navel-gazing, this is first and foremost a materialist argument: time as the most basic ingredient of architecture—a kind of primary substance—and knowledge as that which recursively governs its concrete form and distribution. This substance is not poured over the world as a light or thick topping, but rather constructs the world as we know and feel it, drawing and performing its partitions and periodizations. In Elizabeth Povinelli’s terms, architecture is a geontopolitical technology, structuring geopolitical and ontological relations at once.

In modernist discourse, time was what architecture actualized, what it sublimated through its very unfolding. It was both a destination and a journey, often by the name of ‘progress.’ Architecture variously narrated and dramatized, fulfilled and opposed this teleology, always twinned with it either way. But the story always had a horizon, one that metastasized the singular romance of the modern into a million romanticisms, later neatly wrapped up in the overly capacious theme of ‘post-modernism.’ This horizon was the end of time as we, the moderns, knew it—but not the end of the world, necessarily. Rather, as J.G. Ballard so eloquently explored in his fiction, it was like the chance (and curse) of a constant new beginning, where all forms and categories were ceaselessly up for grabs. An adventure like no other was thus in stock: dangerous and sexy, mysterious and banal. Work is play; play is work. That this signaled an exhaustion in the capacity for things—architecture—to signify has already been thoroughly explored. But not many have noticed the realist, Ballardian desire at its root: the near-certain feeling, despite its obvious science-fictitiousness, of the end of ‘work’ itself.

Here things get complicated, or rather, they get multiple. For the ‘end of work’ as a theme coincides squarely not with postmodernity, but with modernity as a whole. Lodged within the progressive dialectic of modernity—production/consumption, labor/leisure, life/art—is the constant proliferation of models of time. Not just how we should spend it and account for it, but who or what we are in the process. Humans? Social classes? Racialized and gendered subjects? Forms-of-life? Or yet other forms-of-existence? The material and epistemic revolutions of modernity constantly threaten to boil over onto a vast ontological realm that they struggle to contain.

the ‘end of work’ as a theme coincides squarely not with postmodernity, but with modernity as a whole

Scholars have sought to examine how this played out historically. In the 1960s it was about how homo ludens and its habitats—fun palaces and the like—related to the consumerist clichés of a society emerging like a phoenix from the ashes of post-war austerity. But these analyses often disregard the intimate connection and remarkable continuity between ideas of work-play and earlier models of time and forms of life. In fact, Ballard’s genus is less Archigram and Pop, and more the authoritarian curiosity of a gentleman of the British Empire—someone, for example, in the mold of John Maynard Keynes.

Despite his enormous influence on international political economy since World War II, it is sometimes forgotten just how particular and expansive Keynes’ thought was. As if fulfilling Keynes’ script, Ballard’s work plays out to its ultimate conclusions, in literary form, the psycho-social tensions of the Keynesian revolution, which is precisely cast around the very Ballardian conceit of a continuous fueling of creative destruction—the incitation to endlessly consume via the stimulation of productive investment: two sides of the same dazzling, techno-aesthetic, capitalist coin.

In Keynes’ social theory, the solution to the intrinsic perils of unregulated capitalism points, counter-intuitively, to an intensification (rather than a pacification) of extreme individualism, if now guided by a few simple macro-economic principles. As he put it in the conclusion to his magnum opus, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936), self-interest and decentralized markets are indeed the most crucial technologies for economic growth. The argument, however, is not simply economic but rather cultural, bio-political, and ontological. For this economic growth also offers “the best safeguard of the variety of life”; a repository for bio-evolutionary diversification more powerful even than Darwinian competition: “variety preserves the traditions which embody the most secure and successful choices of former generations; it colours the present with the diversification of its fancy; and, being the handmaid of experiment as well as of tradition and of fancy, it is the most powerful instrument to better the future.” Thus, in one fell swoop, the promise of the future is twinned with the conservation of the liberal individualist self and the human species as a whole—a politics and ontology of human life that requires no sudden breaks or fundamental revolutions, only the perpetuation of liberal society as it already exists.

in one fell swoop, the promise of the future is twinned with the conservation of the liberal individualist self and the human species as a whole

Keynes’ famous essay, “Economic Possibilities For Our Grandchildren,” (1930) developed these ideas most explicitly, claiming that “technological unemployment” (“unemployment due to our discovery of means of economising the use of labour outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labour”), would soon upset the very bio-ontological nature of humanity. “Mankind’s economic problem,” the fundamental need to procure enough food and comfort for the survival of the species, would mutate into “his real, his permanent problem—how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.” But this would not be an easy transformation (100 years in Keynes estimation). Rather, as if foreseeing the cult of ludic violence described by Ballard, he dreaded the consequences of such a massive shift in such a short time—“the readjustment of the habits and instincts of the ordinary man, bred into him for countless generations, which he may be asked to discard within a few decades.”

Ultimately, however, despite his anthropological pessimism, Keynes thought the establishment of post-scarcity societies would liberate humans from the drudgery of work, elevating them beyond the limited frames of utilitarian reason and habitual behavior. Such societies would condemn the wealthy to the “euthanasia of the rentier,” burying the cult of money for money’s sake and celebrating instead the virtues of scientists and artists—those with concrete, substantive goals: “it will be those peoples, who can keep alive, and cultivate into a fuller perfection, the art of life itself and do not sell themselves for the means of life, who will be able to enjoy the abundance when it comes.” In other words, it was an argument about the wise management of existential time—that empty formal resource of classical political economy that would now be turned into a concrete philosophical substance—and against the “purposive” man who “is always trying to secure a spurious and delusive immortality for his acts by pushing his interest in them forward into time.” As Keynes writes, with characteristic humor, the purposive man “does not love his cat, but his cat's kittens; nor, in truth, the kittens, but only the kittens' kittens, and so on forward for ever to the end of cat-dom.”

But the shift from the stranglehold of instrumental reason fixated on the future, to a liberated humankind focused on the present, led by liberal arts and culture, confronted a crucial problem: that of the transition itself. Who would lead this, and how? Wealthy people (the “rentier” class), he claimed, had done a lousy job with their free time, squandering it in meaningless, self-serving spectacles and rituals, whether indulging in endless capital accumulation or adoration of cat-dom. In contrast, the working class was even less suited to lead, mired by barbarism and magical thinking. The two classes thus suffered from a similar shortcoming: both lacked civility—one had been too immunized from social ties and obligations, the other one was simply uncivilized. The tense coexistence of both, therefore, threatened to unleash violent revolutionary forces. Even more than plainly cheap psychologism, then, this was an authoritarian argument: the masses could not be trusted to manage societal change because they were not civilized.

there is a persistent fear of violence amidst plenty; a fear which, if carefully managed, can nonetheless be put to work as the central core of a self-sustaining capitalism

In Keynes—like that quintessentially Ballardian trope—there is a persistent fear of violence amidst plenty; a fear which, if carefully managed, can nonetheless be put to work as the central core of a self-sustaining capitalism. Thus, the true revolutionaries for Keynes, as for Schumpeter, are not the laboring classes or the financial rentiers, but the entrepreneurs who are in touch with their “animal spirits” and can channel these toward continuous and relentless business operations. And yet, the rule of the entrepreneur marks precisely modernity’s own stranglehold or double-bind: developing the “arts of life” of non-work, non-specialization, and non-purposiveness requires destroying the entrepreneur’s special skill—the relentless division of labor for the sake of interest—while at the same time, the entrepreneur’s division of labor is essential for the resolution of the economic problem that would unleash “the art of life itself” as a new ontological matrix for humanity; and so on forward for ever to the end of entrepreneurial-dom.

Absent a revolutionary agent that would cut this knot, Keynes thus locks his thought in a dialectical struggle that can only see the future as an endless deferral of existential conflagration. To prevent the conflagration, technocrats, particularly economists, must carefully manage the existing state of affairs with one eye to humanity’s ‘nature’—its inherent violence and individualism—and another to its eventual overcoming, prototyped in the present by that most natural of creatures: the artists, and their dialectical twins, the scientists. The teleology of the argument is set up by the mythical origin point of this ‘nature’ as well as its presumed resolution in a fetishized “art of life.”

A more critical, historical and less ideological view would dissolve Keynes’ strict symmetry and linearity, questioning the virtues of both the origin point and its imaginary resolution. This dialectic is not simply cultural, but is rooted in a material shift at the granular level of the function of knowledge in capitalist societies: since World War II, work in Western societies has tended to become post-industrial—giving rise to ‘information societies’ predicated on work as a primarily cognitive activity. In Keynes’ and Ballard’s imperialist perspectives, such a shift can only mean a de-valorization of manual labor, displacing it toward Southern shores, and a hyper-valorization of professional, technocratic labor as central and desirable. But, as both their endgames betray, liberal professionalism—with its violent morality and post-imperialist élan—is incapable of imagining a socially just, post-scarcity world here and now, a shift that would be quite simple with the re-valorization of all kinds of labor—cognitive, affective, artistic, manual—in detriment of capital and its inherent liberal-humanist framework. In Keynes’ worldview, workers’ movements cannot be anything but brutal and uncivilized, women are intrinsically hysterical, unproductive beings, and the international division of labor faithfully represents the relative capacities of the various “races.”

In Keynes’ worldview, workers’ movements cannot be anything but brutal and uncivilized

In other words, his view of “variety”—human, ontological—is part and parcel of a liberal political infrastructure predicated on patriarchy, racism, and exploitation. Michel Foucault—another author invested, in the line of Keynes and Ballard, with the modern project of self-transformation—also attempted to understand this unique historical combination of an opaque realm of economic exchange (the interplay of self-interest and decentralized markets) with the social ties of blood, soil, tradition, and duty. He found its institutional and discursive infrastructure in the notion of civil society—“the concrete ensemble within which these ideal points, economic men, must be placed so that they can be appropriately managed.”

‘Architecture’ is precisely born out of this political infrastructure as well as being its principal maker: the professionally-managed spatializations that will unite both the apparent nature of humans (their nationality, race, gender, and class) as they allegedly are, as well as what they must become: universally cultured, productive, civilized, and eminently entrepreneurial—forever grasping at the end of work while continuously working ever more.

What would it mean to upend this modern teleology, so inextricably tied to architecture as the prototypical shaper of civil society and the miraculous synthesizer of life-as-art—that is, as the never-ending prelude to the end of work? It would mean re-assessing the history of architecture as a geontopolitical force to show its deep complicity in this endless cycle, re-narrating the ways in which different groups—workers, colonized peoples, women, non-heteronormative sexualities, and others—have, far from being “barbaric,” actually been at the leading edge of attempts to preserve and expand both real diversity, “uncivilized” arts of life, and frameworks of social justice that, most often than not, have absolutely nothing to do with capitalist ‘growth.’

‘Architecture’ in this sense names not a profession or a thing, but a process that continuously re-draws the very limits—in time and knowledge—of who or what we are.

The challenge lies in how to reassert these dimensions of ‘the social’—also a 19th century category—without reifying the foundational oppressions of ‘civil society.’ The mid-∂ƒ0th century thinker Karl Polanyi, writing from a social-democratic perspective parallel to Keynes, sought this reassertion in a return to human “embeddedness” with nature and small-scale communities that had been “disembedded” by the discipline of economics under free market capitalism. But a return to nature, nationalist tribalism, as well as the wholesale rejection of economics, is precisely what we must avoid. Rather, it is the line between the economic and the social—a line that is drawn and constructed through the professional tools of the architect—that must be re-drawn, tearing down the very categories of the social and the economic as essentially distinct or universal. This amounts to re-defining the architecture of architecture, after which it may no longer be ‘architecture’ as we know it, at all.

Such a change doesn’t have to be apocalyptic or linear. It will involve new actors and architects, some non-human, but fundamentally, it has to be constructed from the real varieties of change, the real temporalities of difference, knowledge, and forms of life, that are already among us, repressed and distrusted for far too long. ‘Architecture’ in this sense names not a profession or a thing, but a process that continuously re-draws the very limits—in time and knowledge—of who or what we are.

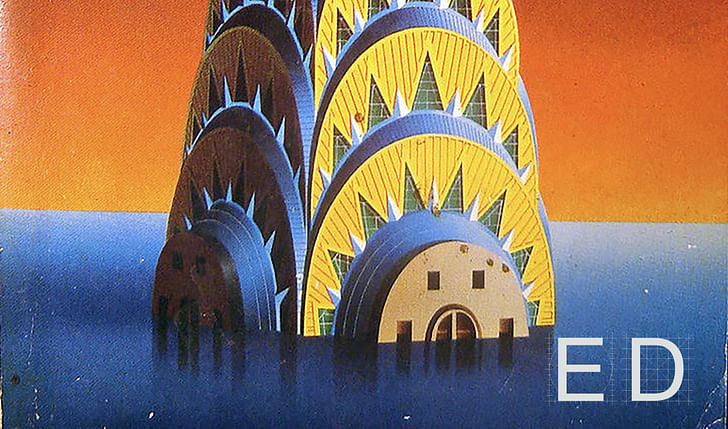

Ed #1 “The Architecture of Architecture” can be purchased here.

1 Comment

There's a lot of talk about "reality" which reminds me of the quest for "honesty" last century. Speaking of eclecticism as the "commodity of form...produced for the sake of market circulation...(and) capital accumulation on the basis of exploitation."...the gaudy spectacle of modern change...aka capitalist growth." That may all be true, but never the less an all too common over simplification of the process of design. Take this quote from the recently deceased architectural historian, Gavin Stamp, who wrote so eloquently about 19th century eclecticism's foremost practitioners, Alexander "Greek" Thompson.

"“..this suggests that the architectural elements, images and devices he did select were chosen not for their historical associations but primarily in consideration of their abstract, formal qualities and their relative compatibility with one another, a kit of parts with the inherent capacity for multiple and incremental assembly in different combinations.”

The reality that is too often dismissed for understandable reasons is that architects and artists of all stripes have been doing this since time began, and no amount of hard facts about the unfairness of capitalism will extinguish man's desire to offer his fellow human with the beauty that can be had through design. I think we can recognize capitalism's worst aspects while keeping in mind that those issues seem to have been the furthest thing from the mind of some who try to bring a little light into this world.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.