In our Deans List series, we speak with the leaders of architecture schools worldwide, offering insights into the institution’s unique curriculum, faculty and academic environment. Following our recent discussion with Jonathan Massey for our podcast, Archinect Sessions, we have expanded our conversation with the architect and historian to talk more about his new appointment at the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning and his plans for the school.

The University of Michigan was one of the first universities to offer courses in architecture, having done so since 1876. In 1906, the university began offering a full degree program within the Department of Engineering and shortly thereafter, in 1913, established its very own Department of Architecture. Since then, the Ann Arbor school has grown to become the largest architecture school in the midwest offering pre-professional, post-professional, and Ph.D programs. With over 80 faculty members and 600 students, the school has become a leader in interdisciplinary education and research offering areas of study ranging from urban design and redevelopment to conservation, digital technology, material systems, and design and health.

Back in September, the school opened for the year to a brand new wing—a $28.5 million project designed by Preston Scott Cohen that added 36,000 square feet of studio and common spaces to the school. Along with the new building, the college also began the school year with a new dean, Jonathan Massey. Succeeding Monica Ponce de Leon, the architect and historian has previously served as dean of architecture and professor at California College of the Arts and spent his time before that, working for several significant architecture firms including Frank O. Gehry and Associates, now known as Gehry Partners.

Massey has long been a champion of transdisciplinary architectural scholarship, most notably through the Aggregate Architectural History Collaborative, which he co-founded, and where he co-edits their online journal, The Aggregate Website. His plans for the school involve working "with U-M students, faculty and staff to generate architecture and planning strategies that expand economic opportunity, increase equitable access to resources, design better health and create the operating system for smart cities.”

What would you consider to be your own pedagogical stance on architectural education?

I think about that in a few different ways. I am someone who studied architecture in a liberal arts context as an undergraduate who did a professional Masters at UCLA, worked in practice for a couple of years and then went back to Princeton for a Ph.D. In my thinking about pedagogy, I'm always working back and forth between a strong professional framework and a commitment to preparing future architects for practices of many kinds. But, I also think about architecture always in an expanded framework of humanistic thinking, learning and scholarship production. I find that I like to approach teaching and learning questions from a disciplinary perspective—i.e. how are we transmitting and advancing the most sophisticated specialized expertise that architects and scholars have developed?—while simultaneously bringing an extra disciplinary or broad lens to it. What is the meaning of this research or this creative production for a bigger world? How does it connect to issues of climate change, poverty reduction, economic empowerment or social justice? How can it be meaningful to audiences and constituencies who don’t have a prior interest in architecture? That's maybe the big picture and then there are all kinds of ways to develop that framework in more detail.

With the politics that exist today and the changing of the licensure process, it seems like that practice is moving into the education. Do you see this happening more?

I have a few different ways of framing it. First, if I were able to work with colleagues to build an architecture curriculum from scratch, I certainly, and probably most of us, would think in very different ways about the curriculum categories and the categories of knowledge and capacity that we're helping our students develop. Categories like history-theory, structures, building technology and professional practice probably don't reflect the state of thinking or practice in quite the way we would want them to. For me, we do the best by our students if we introduce them to practice from day one and keep cycling back to it even as we go deep into more specialized subjects.

The question of practice is not fully captured by the IPAL program, the licensure upon graduation initiative. It is absolutely a positive development and an important pathway for students who are aiming at licensed architectural practice and legitimately want to shorten the time they have to work from starting their degree programs to achieving licensure. I strongly support that initiative. It has a social equity dimension, reducing student debt. It's one way of doing right by students for whom that's the goal. But, there are so many other kinds of practices that professional licensure doesn't capture.

We see architectural knowledge deployed in the world in so many different ways: from conventional client driven practice to consultancies in the health field; from specialized research in building technology and building sector innovation, to working with non-profits or community group municipalities; from startups where people might be patenting intellectual property related to architecture, building and design to companies using a different kind of practice model. For me, those questions of practice are both pragmatic and ethical. Pragmatic: how am I going to earn a living?—something that we don't always address in undergraduate degree programs. But, they also are ethical: how can I have the kind of impact on the world that I want to have?

We do the best by our students if we introduce them to practice from day one

The first part of my answer to your question would be that questions of practice are fundamental to a good educational enterprise and opened up, ideally, in many different ways through summer internships, employment opportunities, and travel study—things that open students to a multitude of paths they might want to pursue. But, there's maybe a longer-term vision which is delivering architectural learning and education in a different set of formats. This is where I'm thinking about the disruptions that we talk a lot about, in and around higher education: technological disruptions, new business models, the unbundling of higher education as people anticipate that the package of learning that we offer in a degree program as a one shot, three to five year deal of full time study in residence in a face to face community.

When we look at the micro-credentials or low-residency degree programs, and other kinds of innovations in how students learn and how we teach them, architecture programs are certainly going to be among the last to be strongly impacted by these developments. Partly because I don't think people have found good solutions yet for teaching design in these new modalities, and partly because the culture of the studio is such a strong foundation as a face-to-face physically embodied, residentially based community of learners.

When we imagine the open loop university—lifelong learners consuming and engaging with our teaching in smaller doses, interleaved with activity out and in the workforce and in practice—I think it's a very promising model. It doesn't necessarily work with the timeline for conventional architectural licensure. But, if we think about the technological changes in architecture as well as in education, there are all kinds of changing standards around sustainability and around learning a global history of architecture that tends to a diversity of experiences rather than a single Western one, told from an elite perspective. There are all kinds of updated knowledge and capacity that people want to tap into. And so, I would like to think that we could move over time toward a more open and geographical model for how students learn so that, even once they're engaged in practice, their relationship to Taubman College, or to other institutions of learning, is not closed off but continuing into multi-dimensional lifelong engagement.

So how would you characterize the program at Taubman College?What makes it unique?

One of the things that drew me to Taubman College and to the University of Michigan, is that it has a very strong, long established powerhouse of professional preparation, especially in architecture, which is 80% of our portfolio here and also in urban planning, where the Master's degree program is robustly well-regarded and highly ranked. Taubman has this very central position in professional education in architecture. We've got something like 11,000 alumni of the college, a deep history, big class sizes. We are the dominant school in the Midwest with a real impact on architectural education and practice.

The second thing is the advanced research capacities of Taubman and the University of Michigan. The University of Michigan is at the very top of public research universities in the volume of research it does and in the number of Ph.Ds granted every year. It's really a formidable place and Taubman College plugs into that and manifests that strength with its Ph.D. programs in architecture, building technology, design studies and history and theory. The new Masters of Science degree is building up those capacities for more specialized work complementing the M.Arch program and feeding into the Ph.D. There is also a very strong M.S. program in digital and material technologies that activates the capacities of the FABLab and of the robotics Institute in the College of Engineering. There is also an M.S. program in design and health that is building relationships to the school of medicine here in nursing, kinesiology, public health—disciplines that operate at the very top of their fields in the sector of healthcare that are expanding and that everyone cares about. Taubman is increasingly activating the capacities of the University of Michigan as a whole to team up with students and faculty to do advanced research in architecture but also transcending what an architectural program can do by itself.

We also need to recognize that the content of our curricula might seem irrelevant to a more diverse range of constituencies

The other thing I should mention is there's a powerful commitment to social justice and equity here at Taubman College that spoke very deeply to me. It's manifest in the urban planning program which works in Detroit and with Detroiters, testing ideas about how an challenged city with a devastated economy can rebuild in a humane and equitable way. The Michigan architecture program has been consciously tackling issues of diversity, equity and inclusion in architecture. The Michigan Architecture Prep program, ArcPrep, is a high school program funded by the University, with support from the Mellon Foundation, in which we offer architectural education to students from several Detroit Public Schools who study with our faculty and get a free introduction to architectural learning that isn't available in just about any high school systems—building pathways into the profession for people who may be first generation college students, who might not have access to the high level of undergraduate education that we offer here by other routes. The program is about two and a half years old. So it's up and running and it has graduated a couple of cohorts. We are excited to keep building, and see what we can learn from it about potential other pathways into architectural learning at the high school level.

The commitment to building a more just world is strong here. We also need to recognize that our choice of curricular topics and the formats that we offer education in are also frameworks that inherently advantage and disadvantage certain constituencies. The content of our curricula might seem irrelevant to a more diverse range of constituencies, who would say: “stop telling me how great Le Corbusier was and help me understand how African-American creativity has manifested itself in the built environment over the years.” I think we need to take the lack of diversity as feedback saying that, in fact, we aren't necessarily offering the education or the practical environment that makes this a compelling choice for talented people who have other options. I'd like to use the diversity question as a chance to also scrutinize what is the core of architectural knowledge and whether or not there are ways for us to reconstruct that and create a field that would be more compelling for a broader range of people.

Michigan is a public university, in a state that is run by a Republican. How do you manage to deal with the very hot button issues?

The University of Michigan has a strong commitment to tackling those problems through a concerted multidisciplinary effort on poverty solutions. For instance, there's a strong sense here that one of our missions as a public research university is to help people figure out what the next economy is for folks who might have worked in the automotive industry and still have skills and expertise but don't have a clear way to deploy those in the emerging advanced manufacturing autonomous vehicles economy.

I have two thoughts about how that's happening at Michigan. One of them is that Taubman College has partnered with the Detroit Planning and Development office led by Maurice Cox. We have a group of about a dozen architecture studios working directly with people in planning and development to model housing and other neighborhood development. Our students are working with planners to test and generate ideas that might get implemented in Detroit and are running architectural scenarios that may help to change the reality on the ground. The autonomous vehicle research facility here on North Campus, right next to the Taubman College, is Michigan University partnering with automotive companies and other experts to see what is the next economy for an industry that really shaped this region powerfully and if we can beat Tesla and Google, or work with them, to find strategies that will unlock economic development possibilities for people in the region.

What do you anticipate will be the biggest challenges you're going to be facing as the new dean at Taubman College?

I think some of the biggest challenges are finding a way forward for meaningful enhancement of pathways to architectural learning. Michigan has a very strong academic innovation group. This is a group that works across campus to help faculty and students develop new modalities of teaching and learning, often technologically enhanced but not always. It's certainly something we're going to be working on. Because of the legacy of long standing strong degree programs, it takes a lot of work and plenty of time to make a dent in how we do things. I think one of the big challenges will be finding concrete paths forward to try some new teaching and learning strategies that we can learn from and can potentially start to implement on a bigger scale.

Do you have plans to develop relationships with departments or schools at University of Michigan outside of the architecture department?

A couple of things are already in place like the certificate in Real Estate Development that we offer jointly with the Ross School of Business. The M.S. degree program in design and health has relationships with faculty in some of the health disciplines. The expertise in digital and material technologies benefits from faculty alignment with the college of engineering which is right next to us and is one of the biggest and most research intensive parts of University of Michigan. So certainly those are some of the directions we'll be building further. But, we also have some good collaborations with literature, science and the arts. For instance, the egalitarian Metropolis project that Milton Curry led when he was here as Associate Dean. The project is funded by a Mellon grant and is mobilizing both humanistic, architectural and urban expertise to think about how to promote equity in our city and around the world. One of the keys to the strengths of a big research institution like University of Michigan is not to go too far with top-down initiatives, but to always be open to faculty initiated paths. The strongest multi-disciplinary collaboration comes from strong faculty alliances. A big part of our success is to balance the strategic thinking and strategic planning, and intentional relationship building, according to a vision and with an openness to the ad hoc faculty partnerships that bubble up.

On September 8th, the school inaugurated a new building designed by Preston Scott Cohen. How did the opening of the new wing go?

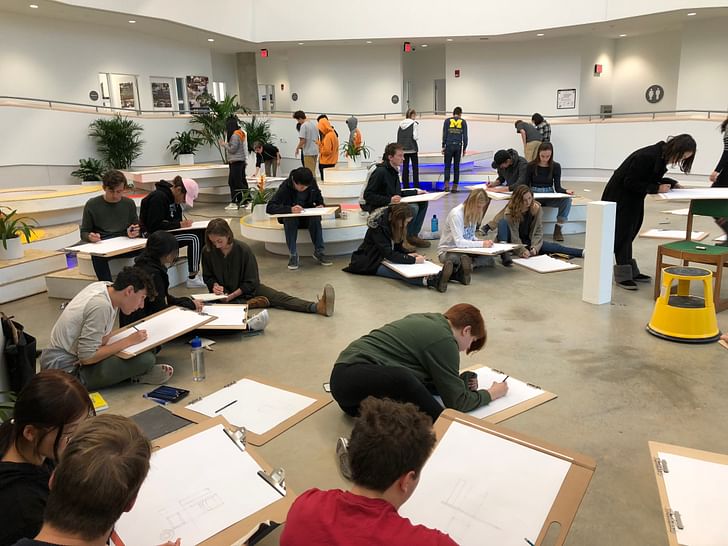

The building is beautiful. It is 36,000 square feet which is about 50 percent of the square footage we occupy in our existing building, so it's a big enhancement. The faculty are in great offices that face one another across a series of bays for collaboration amongst themselves and with graduate students. We've got beautiful new studio spaces, but the heart of it is really this glorious two and a half story common that is much bigger than any space we had previously. It is also formatted differently. It has a big atrium with a large floor plan. When I gave my inaugural lecture there Friday night, I felt like I was at La Scala. There were about 250 people in chairs and then there were another 150 people live in the room, on the second and third levels on ramps and galleries. It's a glorious space where we can come together in a way that hasn't been possible before. We can now go big on lectures and seat audiences way beyond the capacity of our auditorium. But we're also planning to use it for workshops, for conferences, for pin ups, reviews and big displays of student work. I think it's going to have a kind of casual social life apart from those programs; the whole thing is orchestrated with Preston Scott Cohen’s incredibly precise and nuanced attention to geometry and visual experience.

In terms of the dedication on September 8th, I couldn't be luckier than to step into the college at a time when it has completed this big capital project and is launching a new phase in glorious new facilities. Also, because it meant that a bunch of our alumni, the president of the university, other deans and several members of the Taubman family came together and gathered in the new building for a day and I got a chance to meet so many key people who have been part of the success of this place and have ideas and networks and capacities to contribute to our future success. So it was really truly a wonderful way to enter this new role.

1 Comment

"Michigan is a public university, in a state that is run by a Republican. How do you manage to deal with the very hot button issues?"

Is this really a fair question? Or are you suggesting that programs should address hot button issues at large, and you're trying to allow key individuals the opportunity to describe what they think these topics are and how they address them?

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.