Set in Columbus, Indiana, the movie bearing the city’s name narrates the singular friendship between Casey, a young woman deeply passionate about modernist architecture, and Jin, the son of a famous Korean architect who landed in Columbus because of his father’s illness.

Kogonada, the writer/director of Columbus, casts architecture in a central role. The movie is composed of shots of iconic international style buildings, but also intimate domestic spaces as well as industrial and urban landscapes.

Elisha Christian, the director of photography, created moments that directly recall architectural photography, as if the characters were evolving within in the pages of a photo book. Singular buildings also become important elements of the plot as they facilitate encounters and conversations between the characters.

Casey’s innocent fascination and hunger for architectural knowledge reminds of the avidity and passion that young architecture students can have. However, the most skeptical of formalists will be annoyed by her attitude and especially, her claims of the healing powers of the beauty of the international style. But, many will relive through her character, as I did, their first naive love of architecture.

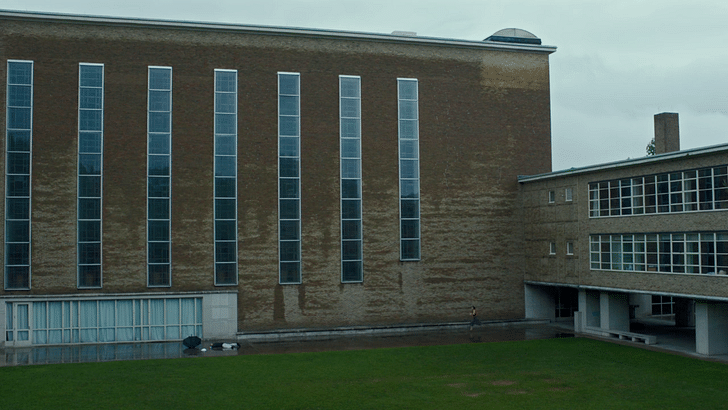

Columbus is a movie about Architecture with a capital A in rural America. Forty miles south of Indianapolis, with a population of 46k, Columbus hosts an incredible number of buildings by famous modern architects, a lot of them are featured in the movie, but not all—among the ones missing is a fire station by Robert Venturi and a school by Richard Meier. Co-founder and CEO of Cummins Inc., a diesel engine manufacturer based in Columbus, J. Irwin Miller created a program through the Cummins Foundation that covered the cost of hiring an architect, chosen from his list, for the construction of public buildings. This lead to the construction of numerous public buildings designed by world-renowned modernists.

In the movie Columbus’ identity seems to be defined by the presence of those modernist landmarks within a working class midwestern town

Columbus surely is an exception to the rule, in which rural architecture goes beyond the charms of the vernacular. We often think of architectural masterpieces to be located in urban centers or a scenic wilderness, but the movie Columbus offers a counter example. The movie, and the city itself, raises the question of the relationship between iconic architecture and “mainstream” America. In the movie, Columbus’ identity seems to be defined by the presence of those modernist landmarks within a working class midwestern town. Casey mentions, with a touch of disdain, the inhabitants' disinterest for modernism, pointing to the common belief that architecture is best appreciated by urban citizens.

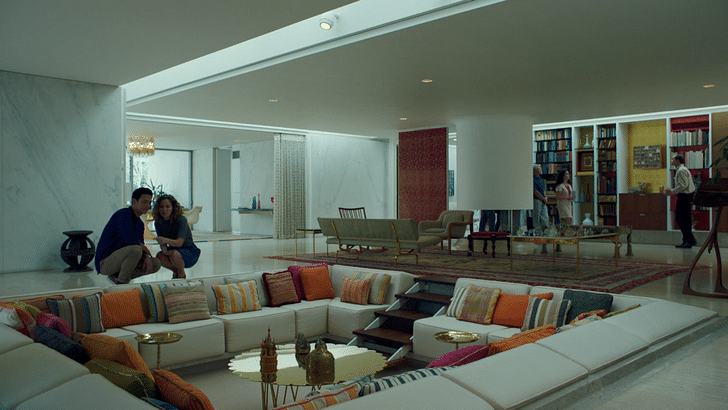

The story is punctuated by detailed descriptions and conversations about Columbus’ most famous buildings, such the First Christian Church and later North Christian Church by Eliel Saarinen, the Miller house and Irwin Union Bank & Trust both designed by Eero Saarinen, son of Eliel, and the County Library by I.M.Pei among many others. Watching Columbus, one will be transported and will virtually participate in a guided tour of the town and its most iconic buildings. You will want to travel to rural Indiana and visit this lesser known Columbus.

Architecture as a key element of drama, becoming not only spatial but also durational, has a lengthy history. The English word 'scene', a sequence of action in a play or a movie, derives from the architectural elements of the skene in ancient Greek theaters. Built or painted on canvas, the skenes served a dual function as both the architectural décor of the play and the back stage for the actors. In the English language, this architectural feature becomes a unit of time and action in a narrative. In similar ways, the buildings in the movie play the role of décor while also being elements of the plot.

Director Kogonada, in conversation on our podcast Archinect Sessions, says “The thing I love about architecture is that it is part of everyday life, part of the environment and not just an art object. I was so excited to put it in time, make for it to be durational to be part of a narrative.”

Columbus is also a romance, or a series of romances, platonic and complex, in which architecture becomes a seduction tool. Speaking of the passion in his film, Kogonada says “I didn’t want to make a film that was just academic, I wanted modernism with a soul, I wanted a film that felt deeply human and passionate”.

Columbus is also a romance, or a series of romances, platonic and complex, and in which architecture becomes a seduction tool

The movie shares structural resemblances with The little house: An Architectural Seduction, by Jean Francois de Bastide, also a passionate story about architecture. This 18th century short novel is both a detailed guided tour of a French countryside house and a romance novel. The short book narrates the meticulous descriptions of the different rooms of the house and the owner’s attempt to forcefully seduce a virtuous young woman by means of architectural explanations. In The Little House, it’s unclear if the “courtship” story is a pretext for extensive descriptions of 18th century French decorative arts or the opposite. Similarly, in Columbus, it is impossible to tell which one of the romantic plots or detailed descriptions of architecture are the real subject of work.

A more contemporary example of architectural analysis intertwined with seduction stories would be Behind Straight Curtains: Towards a Queer Feminist Theory of Architecture by Katarina Bonnevier. This beautifully written play in three acts doubles as an architectural dissertation on gender and space, examines three drastically different buildings—E.1027 designed by Eileen Gray, Natalie Clifford Barney’s temple of friendship at 20 rue Jacob, Paris, and Selma Lagerlöf’s Mårbacka’s designed by Isak Gustaf Clason—and makes for a real page turner.

Columbus marries architecture, drama and seduction to create a beautiful and moving picture.

The movie will be screened at the New York Architecture & Design Film Festival, November 1-5.

Noémie Despland-Lichtert is an urban historian, curator, educator and hot-dog mapper.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.