ConstructLab is a collaborative design and construction practice founded by the carpenter-slash-architect Alexander Römer in the early 2000s. Working on both ephemeral and permanent projects, ConstructLab gathers architects, designers, builders, social scientists, curators, graphic designers, photographers, gardeners and cooks around the ideas of bringing sites to life and creating a sense of place. But beyond construction and design, what really binds those individuals is the notion of ‘togetherness’.

Römer founded the collective network after his participation in Metavilla, the project for the French pavilion at the 2006 Venice Biennale, on the joint invitation of Patrick Bouchain and the French collective Exyzt. In December 2016, I was invited to take part in the first gathering of ConstructLab.

I recently met Alexander Römer in his—of course, collaborative—Berlin office to reflect on the projects and typologies they developed and experimented with through the years. Beyond developing sociopolitical and architectural recipes, ConstructLab produces research on the quality of life that they build together for themselves, for and with the local communities worldwide where they work. Their practice revolves around the question: What does 'collaborative city' mean and how can it be achieved?

“Together as in Building Together”. Where does this idea come from?

Building together is not a new idea, it is rather a very old one. In the medieval times, in the villages, when a farmer needed a new barn, the farmer called the carpenter to realize the construction. But already, as a carpenter, you can’t work alone. You always need a team of two or three people. The skilled workers would prepare for two or three weeks all the pieces for the construction—they would cut and assemble them on the ground. Hence, in order to build the structure up, they needed as many hands as possible: the farmer would ask all the villagers to come and help [erect] the future barn. And well… to drag people to help, what’s [better] than partying?

we understand ‘togetherness’ as a gathering of individuals around a collaborative situation

Within a couple of days, they would work and celebrate together their collective and visible achievement. This is what we call traditionally Richtfest in Germany [in English, ‘topping out’]. This ritual is still celebrated in contemporary construction sites but in most of the cases it has lost its voluntary aspect. The inauguration is another celebrated moment in the construction, marking the beginning of long years of inhabitation, but the real collaborative moment is very much related to the structure of a building. This is what we do, we gather for short times on a site and we call upon the local communities to help us to… celebrate and build together. It is always a nice moment.

I think it is essential to be and work in teams—even more for architects. In ConstructLab, we understand ‘togetherness’ as a gathering of individuals around a collaborative situation. It does not mean that those individuals need to follow one: we really put the emphasis on the collaborative work, at any phase of a project. For projects on a larger political level, reintroducing togetherness into public space becomes a strong political act. Very often, you are not allowed anymore to do anything…in the public realm; the most common collaborative moment in public space nowadays is the act of protest. Instead, we should use public space to create social dynamics. ‘Togetherness’ guarantees the permanence of a project; it makes you stronger. It gives you force.

When talking about ‘togetherness’ you refer to crafts, not to architecture. Isn’t ‘architecture’ enough to gather around?

The most important [thing] is that both crafts and architecture are coming together. How do we create this moment in a collaborative workshop? It is not only about the act of building, but also about the place where that act happens. I’m thinking here of the building shelter, the building lodge, the exchange of skills and knowledge. Even though you come with a certain competence, you still learn a lot by helping others on their tasks. The social aspect of making together is very central to us: eating together, cooking while making the building, investigating the neighborhood, or documenting the process and the project... In traditional architectural projects, it seems that only the final result is honored, when the building stands alone. Within a construction site, togetherness is omnipresent: the workers gather, eat, live, exchange, negotiate, and so on. In ConstructLab, we decide to celebrate the process, from the first time we discuss until the construction is standing and used.

Our imagination sometimes transforms into reality.

To join a collaborative process as you depict it, it seems that the nature of your skills or specialties doesn’t really matter, as long as everybody gathers around the same aim and ideal. Is that right? How does that really work?

Yes. Exactly. The complementary skills are revealed and come together through the process. I think there is a technical—or maybe rational—aspect of making projects together. The question is rather how to join a group…and what is the keystone that holds this group together. In our projects, we use different narrative forms: for example, we often perform a role play within the team. Imagine you build a swimming pool and everybody becomes a lifeguard. Or you build a mill and some become the miller while others [become] the baker. We also like to propose a sort of mad enterprise (Verrücktes Unternehmen) that we need to realize: a bit like the movie of Werner Herzog where they bring a boat over the mountain. It's a challenge: you are moved by the will to go together and do something big, and for that, you need to organize it collectively. We use those narratives to involve the local community. On the one hand, they are curious to see us act and perform and, on the other hand, it relates to something they know better than we do, as our narratives are often created out of their local culture, according to what we observed through our investigation or with the stories we borrow from the local storytellers. Participation is often related to curiosity and enthusiasm, triggered by what people can see. It is always better to create the situation where people come and join you on their own time and will, instead of trying to bring them in.

In fact, if we already use narration in the building process, we repeat the same method in a place’s activation process: the act of building gives a strong impulse, but the act of inhabiting generates togetherness. Inhabiting the place we design and build is very important to guarantee the liveliness of a space once we leave. Somehow, daily life allows you to articulate the projects: going every morning to buy the bread for everybody, for example… Having these daily life rituals make you a real neighbor for the others in a local area. People get used to you, get used to the place and at some point, you can almost disappear as the locals started as well to develop a new routine with that place. Our imagination sometimes transforms into reality.

Beyond imagination and narration, how do you encourage ‘togetherness’ spatially?

The very first typology we use to gather is the circle. You are in a circle to discuss, and we need to do it a lot. We need to talk about what we are doing that day, who is doing what, what is missing, but also about who is not happy with a situation.

Discussing doesn’t mean only like, or love... it is also about conflict, letting this conflict happen and get it solved. The round situation is where you can debate problems. As far as the middle of the circle is kept free, everybody is democratically on the same level. The circle can be generated without architecture, but architecture makes it more suitable, more comfortable somehow. If you start to build tribunes, it becomes suddenly an agora. If you make it more steep, it becomes denser. We tried a lot of different models playing with modules, proportions and dimensions. For example, we did an agora without an exit. I just showed that one in a conference and I was asking the audience what was missing. They consensually answered ‘the entrance’, but it is not true: the entrance is there at first to invite people in, right when you need to enter. On the contrary, once it’s full and the entrance is closed, it suddenly disappears. It's an interesting way to look at it: you were not allowed to escape if there are any problems. You were somehow stuck in democracy and what you need to escape is to discuss and collaborate.

Another interesting model of an agora we realized is the one we made in Italy. At first, she started to paint circles on the ground. Simple lines. She then aligned chairs with different heights around those lines. It was the simplest and cheapest tribune one can actually make.When you plan without use, people have the possibility to propose one

In Mons, in Belgium, for the European Capital of Culture in 2015, it was very different. We had a very large surface to play with. The circle became a big square, a large platform with only one or two rows to sit on. It was a very lively playground, and sometimes even a stage. We performed presentations, a banquet, a yoga class, a concert… everything seemed to be possible there. Among the different activities, we thought of the Île des Réunions that we developed in collaboration with Les Commissaires Anonymes, evoking at the same time the sunny French island in the southern hemisphere—important when you are in rainy Europe—that could be translated literally as the “Island for Meeting”. Every Sunday afternoon, we invited people to debate. It developed in a way that the neighbors would also propose themes to debate. It became again a ritual—the ritual to gather once a week and have this moment of exchange. If you have a problem during the week, you can say: "Hey, let's meet and talk about it in the Île des Réunions on Sunday." For our collective it was also very interesting: to present an issue in the Île des Réunions, you need to think about how to present the problem and you have some time to do so. It is very different from a one to one spontaneous discussion: there, you need to create a group situation and you almost need to get people on your side. Through the island and the regular meetings, we observed the movements and flows of power within the group. Even if we are independent individuals acting collaboratively with a common aim, there are naturally power struggles. I think it is essential to give those struggles a space and to build upon them. One could think of the Theater of the Oppressed of Augusto Boal in Brazil. As theater director, he developed a performative format in order to tackle problems within communities: if problems appear within a small neighborhood, he proposes performative situations where people play their issues on stage, as an active and engaging process to solve conflicting situations. I think it has a real learning value for communities. We actually use the typology of the agora in both ways: to host celebrations and as a spatial form for conflicts resolution.

ConstructLab projects always seem to be located somewhere between the visible—the built structures—and the invisible—the performative content. What are the other notions that are central to your practice?

Instead of visible, [we] speak about “Support Structure”—in relation to the work of Céline Condorelli—meaning the infrastructure and the visible structures we build in order to get to the aim we announce. When we invest a place, there is nothing, so we first need to build the structures for our basic needs: we need shelter, to eat, to clean and to bath. So we build a roof, a kitchen, a shower and toilets. The process always helps to create awareness about our basic needs, and to progressively regain a situation of acceptable comfort. Sometimes we also build a sauna as an extension of the basic amenities, for pleasure... and for the sake of the ritual, of course. Then comes the construction of the projects themselves, the bigger structures, and the first ones serve the other ones. This is all visible. It exists. In Mons, we even called the project Mon(s) Invisible, because it was very much about the invisible relations we are now talking about. You can't really grab them, but you can try to describe the situation, you can recall the story. For instance, we made a one-week workshop with colleagues and friends of ours who are working within the design field on the questions of performance, relations, etc. We called it Mon(s) Diffusion [Blurry Mons] as the notion of blurriness is always a good entrance point. To talk about the invisible, you need to start to blur the visible, to trouble it. It's like fog, somewhere in between—you can't really say what it is.If a project is not unpredictable, you cannot invite people to take control

We also used that notion in Portugal in the Casa do Vapor [the Steam House]. Steam is also blurry and not defined. It was very important to say that we made a house—an easily identified form. We built a structure without exactly knowing what would come in. When you plan without use, people have the possibility to propose one. We had an intuitive idea that the house should host a surf school but we never reach that aim. We first found the surfer who was ready to participate in the project, but he then fell in love with a lady of our team, having no longer time to develop the school... unpredictable. I often emphasize the importance of the uncontrollable, or rather of planning ‘out of control’. As you can imagine, it is very difficult to defend this idea when we talk to politicians about our methods. Why would they give money to make projects out of control? Indeed, they are out-of-control, but still, within a frame and with a certain direction. It is never chaos. If a project is not unpredictable, you cannot invite people to take control, to feel responsible for it and unleash their potential. It is very satisfying to be surprised by what they become.

Sometimes it can be hard if the result is not fitting your first intentions, but, in fact, the project appears to be more grounded and much stronger because it comes out of a situation, a constructed idea, a collaborative mind and work. I don't have yet the answer on how to make this happen on a larger scale, on bigger projects. To deliver an adaptable structure? It is so complicated.

Your collaborations take sometimes some unexpected turns, whether it is through the variety and the quality of your collaborators or the extent of your ambitions for a site. How do you see the future of the project?

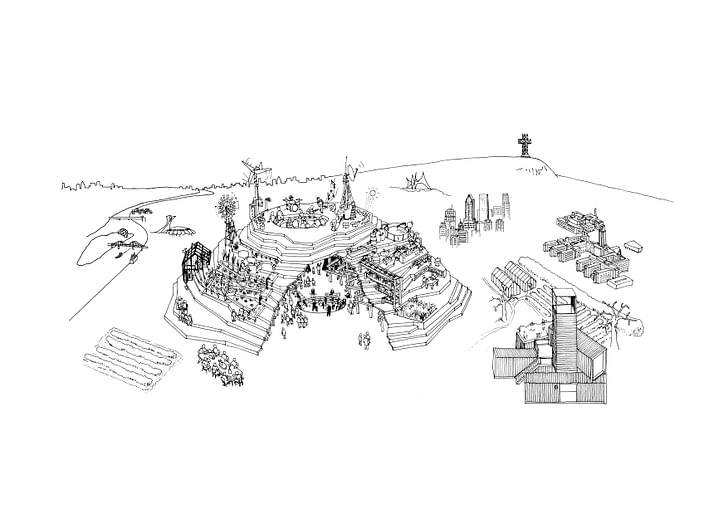

For Mont Réel, our next project in Montreal we proposed to work around three types of forms: the constructed form, the living form and the popular science form.

The constructed form is self-explanatory. The living form concerns also a construction, but rather the one of a performance: we invite artists, musicians and a choir to join and perform while we build. They will accompany us through the construction but as well present the musical result for the opening event. Thanks to their music, the construction site will have the potential of being reproduced. Through the power of improvisation, the music will express a strong relation to the construction process. This idea allows us to gather other kinds of people: the ones who are not able to build or the ones who can't be there everyday but still want to engage in other ways.

The permanence of our projects doesn’t depend on us, but rather on the will of local actors

The popular science form is directly related to the site. It is located on the future extension of the science campus of one of the biggest Montreal University. In the next five years, the campus will be built and defined. Therefore, we proposed in the meantime to displace the science and research laboratories to the public space we will inhabit, whereas those uses usually take place between closed walls. We think it is relevant to put this knowledge into a frontal situation where it has to deal not only with researchers and academics but also with people who carry their dog around. How to make such research [comprehendible] for the people? Local communities develop more and more interest for ecology and alternative energy that they could apprehend and experiment on site.

Once again, we engage towards uncertainty: we know we can achieve the constructed form as we have the competences to produce it. For the living form, we know that by inviting the right people, the magic might happen. In contrast, the popular science form represents here the biggest challenge: while our team will stay only three weeks, the scientific research residence out of the walls will run over a one-year period. The permanence of our projects doesn’t depend on us, but rather on the will of local actors and decision makers who see in it the local potential beyond our presence on-site. Who knows… maybe we will find some crazy scientist who engages and joins us on the three weeks of our intervention to present their first results for the inauguration. The future is definitely made of surprises.

ConstructLab has recently published a new book Livre Invisible. Check it out here.

Joanne Pouzenc is a French architect and urban explorer who found an urban refuge in Berlin. She tries to escape from her beloved architectural fate by diversifying her centers of interests and offering her views on the contemporary urban conditions via designing, curating, writing ...

3 Comments

This is probably the brightest spot in architectural discourse I've stumbled across in years.

Using architecture's specific methods and skills to promote communities and open conversations? Hey look, architecture can actually help resolve conflict! This is worth more than all of the 'No Wall' cartoons/complaints put together :)

James you should also check this interview of the Venezuelan collective PICO (>>> http://bit.ly/2nYz2fG) in which co-founder Marcos Coronel claims that "it is actually necessary to assume a new leadership, closer to the people who live in this emerging contexts, by being able to work as design technicians, as citizens that build social relationships and as interlocutors between the institutions and the people. Only under this condition of transversality - where architecture is a backing platform - will architects eventually become true agents of the society’s transformation, managing to rethink urban strategies and ways of building in the city." ;)

Great to see ConstructLab featuring on archinect!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.