How is the city made? Who is it made by? Who is it made for? These are the questions poised by In-Between Economies, an interdisciplinary research platform based in Copenhagen, London and Oslo. In their view, the only way to address them in the 21st century is to expand beyond the purview of architecture or urbanism. “Urban life, and our experience of it, is a complex mix of economic systems, social relationships, and infrastructural spaces,” they tell me. And to grapple with it, we need to start talking with people besides architects.

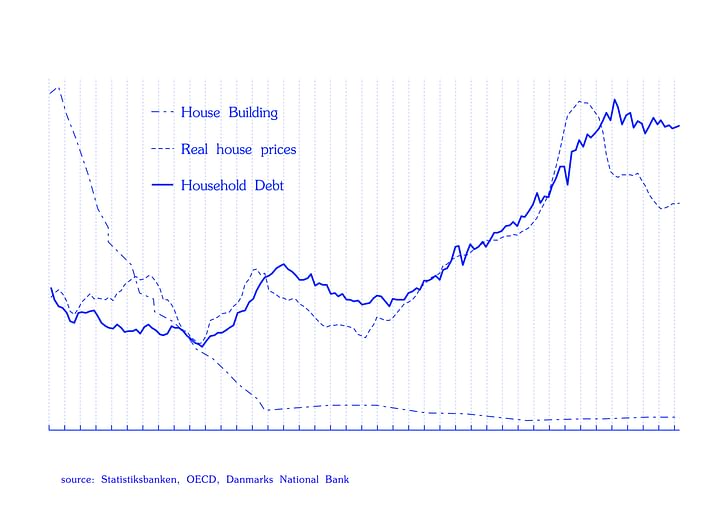

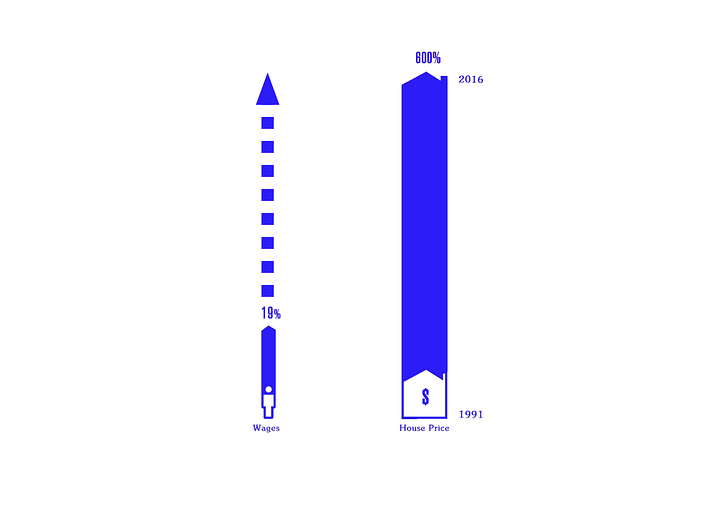

The contemporary city is much more than its built form (although that certainly does structure our experience of it). Cities are shaped by both local economies and global markets, which don’t exist as distinct entities but rather co-exist and even co-constitute. For example, our homes have become a form of debt that, when bundled together, are bought and sold at high speeds around the world. When, like in the 2008 financial, people lose faith in the possibility that those debts will be repaid, the impact reverberates and spreads around the world. Banks fail, governments collapse—and we lose our homes.

If we want to comprehend how our cities function in the contemporary era, we need to start talking with people outside the discipline—experts from fields like economics, but also the broader public. At least, that’s the thinking behind In-Between Economies. In order to do this, they host lively events (intentionally using alternative models from your typical, staid architecture ‘debate’), publish texts and forge collaborations across disciplines. I talked with In-Between Economies over email in order to find out more about the project.

What was the impetus for In-Between Economies?

In-Between Economies (IBE) was founded as a reaction against a distinct lack of interdisciplinary discussion on what drives urban development: how is the city made? Who is it made by? Who is it made for? Try as they might, no one profession or institution has the answers to these questions, and our generation is witness to the inability of design to confront the social or political dimensions of this reality.Urban life, and our experience of it, is a complex mix of economic systems, social relationships, and infrastructural spaces

In that sense, IBE was a way to question the perceived logic of professional practice, that by separating out and interrogating our problems we’ll stand a better chance of finding solutions. This might have worked during the Enlightenment when our understanding of the world was shaped by the creation of distinct professions and disciplines. Yet, in the finite, interconnected world of today, that logic needs a reboot.

So our aim with IBE is twofold: first, to acknowledge that design solutions are not static but inherently fluid, and we must do what we can to facilitate a much wider conversation on how to ask the right questions, not simply provide the right answers. Second, to develop our own conceptual understanding of both the role and communication of design in this context of constant flux.

Could you elaborate on the “in-between” of In-Between Economies?

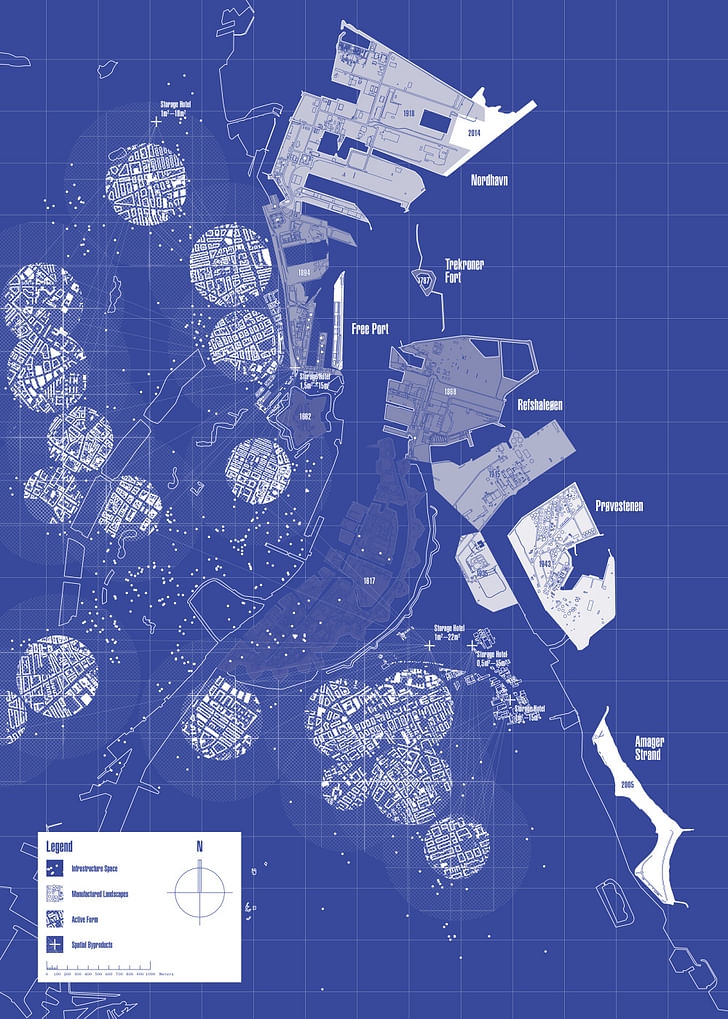

Urban life, and our experience of it, is a complex mix of economic systems, social relationships, and infrastructural spaces. The city exists not only as material form, but also as a spaghetti of ‘complex interdependencies and intersecting narratives’ that demand a new logic of how to understand them.

Dan Hill refers to this as the ‘dark matter’ of design:

"an iPhone, say, is successful not simply due...design but also Apple’s lawyers, intellectual property holdings, their creative interpretation legislation..., their deals with telecoms companies, with record labels, with movie studios, their organisational culture. This is all dark matter. You can’t perceive any of it, holding the iPhone in your hand, but it is all this, and more"

What’s key here is this paradox of an unknown, or an imperceptibility, of design processes that’s then cast against a pervasive brand identity. This is the space in which we are interested—in-between the global and the local, where the largely immaterial movements of the global economy meet the local, material scale of the everyday.

I’m interested in this description of the city as “a spaghetti of complex interdependencies and intersecting narratives.” Can you hash that out a bit more and explain why it’s vital to understand urban life in this way?

We think it’s impossible to talk about this without referring to the crash of 2008. Being in university and studying architecture while this happened you had this realization that everything you were being taught to value, to learn from, to argue for...it just didn’t fit with how reality was playing out. There was this huge blind spot.

Then you realized it wasn’t just our own profession that was asking itself these questions—economists, politicians, sociologists, anthropologists, they were all questioning the reliability of their own expertise.

We would argue that we have relied on an oversimplified model of understanding the inherent complexity of how the city is made. We don’t have the strategic view, we don’t understand the interconnected nature of the world and we don’t have the knowledge of how this affects people’s everyday lives. The global financial crash was a huge wake-up call for the need to equip ourselves with a greater understanding of how our collective ambitions are realized and safe-guarded in real life.The economy is a design. In fact, it’s multiple designs overlapping and intersecting each other.

What role could architects and designers play in this expanded conception of urbanity? Can economies and economic conditions be re-designed?

Architecture is a peculiar thing. As a profession it has become fixated with providing a particular type of consumer product—a building—even though this is about the most complex and time-consuming thing solution to a given problem. This is not because architects are ignorant, or naïve, it’s just that the output of any design is largely defined by the questions you ask of it from the outset. There are many designers and architects coming to this realization and starting to reconfigure their skills to address it. The role of ‘design’ in policy or decision-making has been talked about a lot—with a fashion for ‘design-thinking’ in the business and management world gaining a lot of traction in the early ‘00s. In many ways this underestimated the change that was needed and brought a fairly superficial notion of experiment and research to corporate culture.

Designers—due to their ability to juggle information, prototype future solutions and iterate along the way—are well-placed to hack into the defining economic and political logic that dominates urban life. The economy is a design. In fact, it’s multiple designs overlapping and intersecting each other. It is only modern economics (or neoliberalism) that has aimed to assert itself as if it were fundamental law. Not only has this debased our decision-making process, but it has frozen us in apathy while provided the perfect excuse for denouncing its detractors. We have to find ways of combating this logic that are smarter than either protest or critique.

Tell me a bit about the events you throw. I’m interested in how you try to move away from the typical, consensus-based form of most academic ‘debates’.

We felt this frustration at going to lectures and debates and feeling as though we were there as consumers, not active participants or contributors. For some of the problems we’ve outlined above, we felt like we need to try and change that. When we organize a public event, the first thing we do is to frame a provocative question, something our speakers and audience can react to. This usually stems from a particular piece of research we’ve been doing, or discussions that have been building up around us. These problems are never binary, but people need something to bounce off.

All of our events are always free and open to the public—something we are very committed to. We try to hold them in public buildings that have something strange or intriguing about them in order to create a different atmosphere than the expected. These buildings being located around the city also emphasizes our aim of reaching out as broadly as possible.

What’s most important is what happens afterwards

We pay a lot of attention to try and make the events casual, or relaxed; music, lighting, beers—it all adds to the feeling that this is a comfortable and safe [environment] in which you can contribute. Another key thing is to give as much time to the audience as possible, or at least as much as the speaker. Getting that knowledge and reflection from the audience is vital, and offering multiple points to do that makes the event feel more like a conversation.

When organizing a panel we aim to get a range of disciplines and try to engage with fields beyond architecture and more towards experts and researchers from fields of economics, sociology, technology, urban planning etc. to gain more agency. At our last event ‘LiveabilityMAX’ we were discussing speculative city development, housing, marketing, city governance. We had city officials, architects, real estate agents and economists and it generated a really useful discussion about how each profession could lend their agency for building an argument for change.

What’s most important is what happens afterwards. If we left it there, we would be falling into the same trap as the one we were trying to escape. We use the conversation and the material generated by the discussion to approach public bodies, businesses and organizations to either prototype the next phase or to build more knowledge—whichever feels most needed.

Keller Easterling, Christian Borch and Kristoffer Weiss discuss economy and architecture from In-Between Economies on Vimeo.

What is the future of this project? Where do you hope it will go?

With IBE we want to continuously encourage and host events where an interdisciplinary forum of experts and the public can come together and discuss matters of urban development. Alongside this and our research, the ambition is to go deeper into active collaborations across the fields and strive for engaging in direct on-the-ground projects. In essence, our goal is to act as a R+D lab for building movements for change, building prototypes for how design can exploit the soft skills of activism, collaboration and communication while leveraging the hard skills of professional practice.

Lectures, debates, viral marketing, digital platforms—they are all part of the new design vocabulary. We want to experiment with mixing these inherently temporary concepts with the more traditional design work as a way to build a more robust knowledge and understanding of the complexity of the city. We think the most exciting part of this is that we are not alone. There are many other small groups and collectives that are travelling this journey with us. In an age when we expect knowledge and expertise to be free, and have tools at our disposal to make this possible, many small groups can aggregate their experience in a bid to try and form the next generation of institutions and infrastructure.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.