Andrés Jacque and the Office for Political Innovation have been tasked with renovating CA2M, a museum in central Spain. But, rather than close the building for a few years, they’re keeping the museum open during the remodel. In the process, they’re making the act of architecture itself—in all its messiness—an object on display.

It’s not the first time that Jaque has contended with what it means to exhibit architecture. Alongside built work, his studio often shows in architectural exhibitions and biennials. But, when they do, they don’t rely on plinths or models and there are no renderings pinned to walls. Rather, they take to different media—video, performance—to exhibit architecture as an object that is, itself, in a sense, designed. For example, with the performance piece Superpowers of Ten, his studio revisited the classic Eames’ film, unpacking the political and social dimensions that the original glosses over. It turns out that the framing can change the picture as much as zooming out.

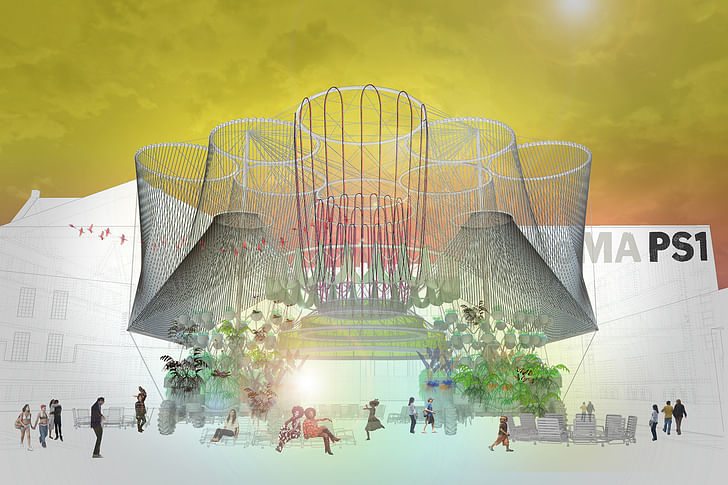

In other words, the Office for Political Innovation exposes the way architecture, as practice and thought, is delimited by sociopolitical and economic forces. At the same time, they attempt to reveal how architecture participates in the construction and materialization of these conditions. For instance, the centralization of water infrastructure is revealed to be a mechanism of environmental racism and classism in Cosmo, their installation for MoMA PS 1. Cosmo sprayed revelers with water that had been filtered on-site, providing an alternative image of how we can relate to resources. Acupuntura, the project for CA2M, endeavors to show that architecture is much more than the realization of a finished object, but rather requires navigating a tangle of bureaucracies and regulations. With each project, the goal is to not just expose but also propose alternatives to how we think and make architecture.

I’m interested in how, on the one hand, your project Acupuntura is typical of what you’d normally think of as architecture—you’re renovating and changing the space. But then, on the other hand, it’s presented as something like an exhibition of architecture. ‘Architecture’ is being put on display. So, I’m wondering how you balance the need for the project to be at once effective in material terms but also performative in that it’s viewable as ‘architecture’.

That’s a very good question. Basically the story of this project, Acupuntura, is that we started with a building that never worked that well, which was constructed around 15 years ago as a museum of contemporary art. The institution of the museum recently got a very important donation of significant art—a contemporary art collection of great importance with names from Damien Hirst to historical artists like Dan Flavin or Donald Judd. So this collection was being added to the original collection of the museum, which was already significant in many ways, and it turned this museum into an important spot for contemporary art in Europe. The building never worked that well because it was designed for a very old notion of [what a] museum [should be]. The actual trajectory of this institution went far beyond what the building allowed to do. So there were two options.

One was to basically demolish the building and do a new one on the same site. This first option would mean that the museum would be closed for something like three years. The second option—our proposal and the one with which we won the competition—was basically that it was very important not to close the museum because, rather than [just a] building, it was a network of people mobilized by the dynamics that the museum itself as an institution promoted. Basically, it was like closing a city for a while and that was very damaging. We argued that the museum needed to be transformed but without going through the process of closing. And that, on the one hand, opened up big difficulties that we’ve had to respond to, but, on the other, it also opened up so many opportunities.

the architecture becomes content, becomes displayed in itself

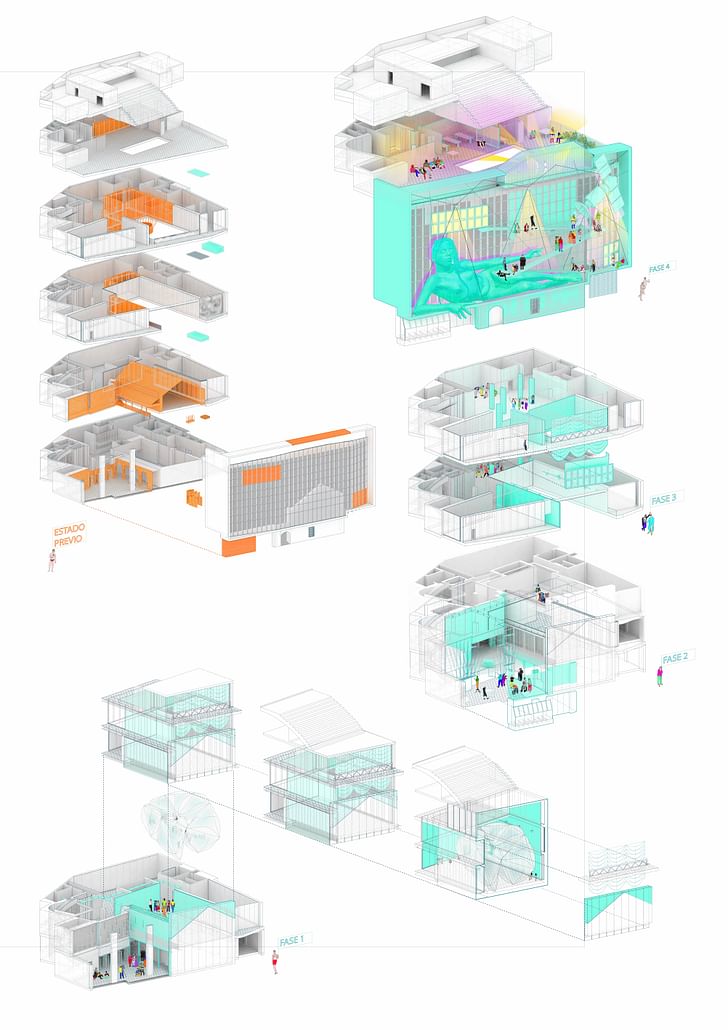

In short, the project is based on three principles. The first one is to distribute the transformation of the building within time. So, rather than a final version of the building built at once, the project is a timeline of actions that accumulate, one on top of each other, to produce a totally different material setting and infrastructure for the museum. The second thing is that, as we do it, it can be coupled—and this goes to your question—with the contents of the museum. So, on the one side, the architecture becomes content, becomes displayed in itself. Meaning, [setting] is discussed, or scrutinized, and analyzed by the public of the museum. But also, it becomes an action of enrollment. Architecture becomes a process of enrollment… The public of the museum—the different groups that work with the museum—they all become part of the transformation of the building. So the whole process becomes the museum in itself. And that has already been super amazing; the opportunity of having people like Sergio Prego and Cabello / Carceller as part of the construction process has been really so enriching.

But the third one is that [the project] applies what I would define as a precautionary principle, which means that by doing things sequentially there is a great opportunity that a tiny reaction gets to be experienced and discussed—not only by the architect or the people that are managing the museum, but by a broader network of affected actors who then have the opportunity to inform the next steps with their opinions of what has already happened. So I would say that the architectural process becomes a critical process, a process that is critically equipped to prompt reactions and use those reactions for the benefit of the next step.

We’ve recently been planning the next step. We have a meeting actually the day after tomorrow to define the budget and the scope of the next step. It is already, let’s say, the information that was prompted by the reactions of those who experienced the first step of the transformation. So, for us it is a very different way of doing architecture, and one that we would like to keep promoting and working on.

I imagine that you have to navigate a whole kind of architecture of bureaucratic protocols and safety precautions, etc. if you’re working on the building and people are in the space at the same time. Can you tell me about that?

The architecture is really challenging and in many ways innovative, but it’s placing the innovation in very different locations. It’s not that we’re trying to do a super light façade. We are doing things that are materially very challenging. For instance, we are developing with some hi-tech companies a digital façade that will make it possible for a huge number of actors to interact and produce big transformations in the façade—not only in the lighting of the façade but also in the movement of elements of the façade. That’s just an example, but this innovating is also in the frame, the legal frame in which works become integrated in society at large.

Precisely what you were saying, it’s been very important: how do we organize the construction site in a way that could be shared by others, in which artists could be working and using the machinery that the construction building company have placed on the site? This has been very difficult and actually we had to work with a number of lawyers to make it possible. For instance, to challenge the limits of insurances, the legal frame, but also [having to work] with people in the museum, mediators, that could make sure that everyone in the site, even though they might be the public coming for a discussion would be wearing helmets, gloves, and all the elements that are required by building regulations.What is the way that the ‘how’ becomes an opportunity for innovation and not only the ‘what’?

So, like you said, the whole process is very challenging legally and in its management, but that’s precisely why it’s very important for me—this management. Because, for instance, you make it possible to bring a public into a situation that is not purely secured, and they can enjoy and discuss and get the benefit of [experiencing] those situations that normally are blackboxed, separated from society and totally kidnapped from the way we construct criticism. For me it’s very important and it’s something that I would suggest is kind of a leading edge where architecture can find many other pacts with the rest of society. I’m very interested in that. It’s not the first time that we’ve worked on something like that.

We did, years ago, a project to make transparent the process of constructing the Ciudad de Cultura, the building that was constructed by Peter Eisenman and Partners in Galicia. [We produced a series of] cultural actions to make the building site transparent, to make it possible that the general public could follow very extensively and very closely the evolution of the site, from the consumption of the budget to the knowledge that the experts were using to construct the buildings, to the discussion of what would be the use of it and the way that the architecture would cater to them. All these open methods or these actions to make the process shared and participated in require a lot of design. For instance, to, of course, make sure that the public couldn’t get into danger during the process of being part of the building site. Now the second project that is dealing with this is even more exciting for me because it is implicating design and material transformations as part of the same plan. So it’s not that we are adding that on to an existing architectural plan, but this is actually the architectural plan itself. For me, this opens a huge opportunity to discuss not the final result of buildings only but what is the way that we can innovate in between? What is the way that the ‘how’ becomes an opportunity for innovation and not only the ‘what’? And this is what we are after.

Our office is called the Office for Political Innovation because we believe that architecture has great opportunities to innovate in the processes, in the way people and resources and means get together to change society through architecture.

Can you hash out a bit more the political implications of exposing the processes behind architecture? It’s almost like an expression of architectural vulnerability. Architects tend to like to show their buildings as if they came out of nowhere, as if they spring out of their head, but to show that architecture is actually quite limited by other forces is really interesting and bold.

Basically, architecture in the 90s, I would say, and in the 2000s, went very extremely into presenting architecture as purely the final outcome—like fixed images that would come from nowhere. We believe that it’s precisely in the process of both mobilizing society to make it happen, and in the afterlife of buildings once they are photographed and opened, where probably we can find the best opportunities to render architecture political. Or it is already political, but to maximize this political performance.

Because in the making is where you can find the opportunities to decide what is the way you deal with materiality, with labor, with the use of resources, with discussion. And also to whom that discussion is open. All those spaces for politics are blocked and blackboxed, let’s say, rendered invisible and therefore inaccessible. The final, perfect images of buildings hide all the decisions, all the means, all the contracts that were required to make it happen. And our office is determined to work on something that could be described as the black box of the processes.

We would like to open the process and make it visible so all the details of the decision making—of the rejection of alternatives, of the selection of materials, of the way the resources are used—can be open to discussion and can be actually confronted. Therefore the result couldn’t be that important. Much more important would be other facts, like the precedence of the elements that are assembled in the building, the future expected for them, the legality in which the whole process happened, the alternatives that were rejected, how the project is incorporating already a plan for the future. All these new questions are immediately activated and all of them are very political, I would say. They are activated when the black box is opened and we replace conversations about style—and how beautiful it is and whether it’s shocking or not shocking—with a much more complex discussion in which even the aesthetic facts are viewed within a larger context of discussion. And for me that is very, very important.The final, perfect images of buildings hide all the decisions, all the means, all the contracts that were required to make it happen

When we did, for instance, a project for PS1, our project was basically to bring an alternative to the way water was treated in a place like New York City. Water management was basically treated as a hidden process that was secure, only considered the domain of experts, protected from terrorist attacks and super centralized. The transformation of these infrastructures, of wastewater treatment plants, for instance, was totally impossible. It can’t be adapted because the amount of money that was spent to centralize all the sewage system of New York makes it impossible to transform that network.

What we were proposing was to look at other traditions of infrastructures that were scaled down, that could cohabitate with users, that could actually be very transparent so people could understand how they worked and take decisions in the way they wanted to relate to it. So making toxicity something that is not sent to other states, to places like Pennsylvania, for instance, but something that could stay in New York and therefore could not produce this huge segregation of society where the rich live in places like New York or Boston totally apart from toxicity while the poor people live in places like Susquehanna Valley surrounded by incinerators and fracking.

This way of dealing with wastewater was something that we could challenge, at a small scale, like a David against Goliath, just by showing an alternative, an architectural alternative that could provide people with an opportunity to say, ‘Okay, things could be different.’ And for us, architecture is about this. It’s about providing experiences in which alternatives that could provide better horizons, political horizons, could be experienced and become available as something that people believe is possible, that can be achieved and could be scaled up and somehow inform our society at large.

That’s almost diametrically opposed to the way that, for the last 20 or 30 years, global cities have worked—driven by these very opaque processes of finance that few people actually understand. This dynamic could be said to extend all the way to the housing crisis where, because people didn’t understand the economics behind the housing market, they took on sub-prime mortgages—were actually encouraged to in spite of the obvious risks.

This is super important because basically what we’re trying to do with the Office for Political Innovation is also to challenge the way politics are understood in architecture. You see that there are many moments when architects will claim that architecture should be more political, but the way of thinking those politics are, by and large, very un-architectural. They were basically about protesting, about stating things as architects, as people, as cities, and about being committed personally. For me, that’s super good and that’s very interesting but it’s not what I would like to do through architecture. I don’t want those things to become manifestos or, let’s say, proclamations. What I would like to understand is that there is another form of politics, which is the politics of materiality.

Material politics are performed and produced by the way stones, bricks, metals get put together… Basically, the way we compose our material environment is also a form of politics because it is making certain realities more likely and others kind of blocked. These are the politics that I believe architecture can reclaim. Your comment about housing is very important because we perceive, for instance, apartment towers now like things that are just happening—and architecture can just provide the image and the sculptural aspects of them. But when you see in detail the way they are composed, they are a part of very large combinations and compositions of design that are happening at very different scales, from the territorial decision of, for instance, doing fracking—and I was mentioning this before—in Susquehanna valley but not in New York, banning that possibility from New York, to the whole process of declaring New York a place where garbage and solid waste would no longer be treated, by closing places like Freshkills. But also to the design of new taxation systems that could promote billionaires to come to New York, and would promote low-income people to move away to the inside of the country. And to the actual design of many things, the design of parks, the design of, of course, buildings, but also the design of regulations that make it possible to accumulate the air rights for the whole block. If the lots had 16 feet, you could transfer the air rights of one lot to the next one within the same block and that may be possible for the towers to grow and to therefore produce a new architectural product. the way we compose our material environment is also a form of politicsThese helicopter view apartments could therefore be marketed above the price of any previous existing apartment in New York.

So, if you put it together, there’s a lot of design here—territorial design, legal design, taxation design, apartment design, interior design with legislation, and urban regulation design—that was brought together to produce the realities of New York housing that we live today. In the same way that all these things were brought together and coordinated to bring this reality, we believe that it is the task of architecture to introduce alternatives. To produce other situations in which all of those processes can also be somehow weakened by the presence of alternative ones, which could create cities that are more participative, less segregated, more inclusive and more exciting in many ways.

Personally, I am very active in all sorts of politics, but I would suggest it is also the time for architecture to understand that there is an agency in the way it composes materially things together, and that is the kind of agency that we would like to use in our architecture. So, your question is very relevant, it’s exactly that discussion. What forms of politics can be best mobilized from architectural practice?

What do you see as the relationship between this way of thinking—of exposing the mechanics behind architecture—and the work that you do that is exhibited, such as Pornified Homes or Superpowers of Ten? You show often in traditional exhibition settings.

One thing that, in my opinion, is very important to acknowledge is that architecture as a discipline has many different formats. When we see historically architects like Frank Lloyd Wright, Louis Khan, Le Corbusier, they were making buildings and, in order to make buildings, they were also doing many, many other things. They were doing movies, they [making] drawings that they would circulate, they would do manifestos, they would intervene in many public debates, they would propose unrequested proposals for Philadelphia, they would describe traffic differently. They would do many, many things that created an atmosphere in which their ideas, their way of engaging with society, would be somehow conveyed and shared with others and discussed with others.

For us, this tradition of parallel actions that are not only providing buildings but also preparing the environment for architectural actions to happen—it’s very important. For instance, it is now the anniversary of Superpowers of Ten, which we worked on a few years ago, in response to the [Eames’] Powers of Ten, because the 1977 movie proposed thinking about the connection between science, architecture, and daily life as a very lineal, undisputed environment, like as if science would be there to resolve any need for alternatives, any conflict, any controversy. At the end of the day there was a single reality that could be acknowledged, recognized and interrogated through science. But what was very important for us was to see how far we, as a society, were from that moment in 1977. Many years after—40 years after—we could see that the relationship between daily life, science, and architecture was totally different. Now, whatever it is we wanted to see [in the film] became very [politicized]. Climate change, even the beaches, our relationships with gender, our notions of nature or the way we construct our societies in relationship to others—all of these topics that were installed in that movie as kind of easy to handle, they were not that easy to handle any more. Actually, they were never that easy to handle. At the time, they were [implicitly] claiming—the images were claiming—that we all constituted a single society, that we were all living in neighborhoods like the ones that they were describing. […]

So, for us, what was important was to propose a different version, a reenactment of [Powers of Ten] that we could show our colleagues and discuss with them how architecture was very different, and how we are dealing with very different notions of society in which we acknowledge that nature is very fragile, that we have to be careful with it, that our relationship with others is also something that is loaded with that conflicts and that we have a responsibility to promote inclusive ways of dealing with them—and so on and so forth. We basically reconstructed the movie showing that architecture now faces a very particular challenge. That is: how to move from a time in which we thought technology and science could bring simple solutions that could end problems to a moment in which we understand that that fantasy is no longer possible. We are not going to resolve any of the big problems we are facing and we have to move to a political ground in which we basically manage the problems but not make them disappear. And that is probably the displacement from a modern society to a society that is facing ecological politics as the ground in which we relate to each other. For me, it’s very exciting because I am convinced this could also open the door for architecture to become much more relevant, not something that serves power but that gains power in itself, but also that could produce good environments to live in.How do we gain agency in what necessarily becomes an ecosystem of guilt in which also we participate?

There’s an architecture of architecture exhibitions as well. For example, BP sponsored the Chicago Biennial, where you showed Superpowers of Ten. You designed the exhibition architecture for this year’s Istanbul Design Biennial, which was sponsored by the largest petrochemical company in Turkey. Does this matter?

Yes, that matters a lot. It’s a very good question. And we could go on and on and on and we could see that whatever we do, it’s somehow related to many powers that are totally misaligned with the discussions that we want to produce. The question is very relevant and, also, it’s not easy to respond.

On the one hand, we see that there is literally no possibility of being away from the network which [produces this guilt]. For us, it’s very important to see that we could never find the possibility of leaving [it]… So basically there is this fundamental contradiction: the impossibility of getting pureness, of becoming totally detached. It’s a contemporary condition. We belong to ecosystems of guilt and this is something very complex because it requires a responsibility from us.

In my opinion, the way of dealing with these contradictions is to problematize them, to make them very visible, to discuss them, to put limits. For instance, we can build that Biennial, but we are going to present our work, we are going to keep talking about oil, we are going to be protesting about the way it is centralized and the way that damages are concentrated in one part of society that’s segregated from its benefits. So for us, what is important is to want to make it very clear what is our position and to introduce the complexity of the situation from which we are discussing as part of the discussion. Of course, there are huge limits. There are companies we would never directly work with. There are positions that we would never share. We would never allow our work to be censured. We would never allow our work to directly cater to a force we are trying to confront, at least consciously and at least in a way that we could avoid.

At the same time, we know that we are, by just existing in society, linked to many of the forces that we are confronting. But it’s very important conceptually and personally to acknowledge that our capacity is limited. Not only us, but everyone. And that we end up being part of these ecosystems of guilt.

But we are also part of many other things. We are also part of the communities of the commons that Silvia Federici is defending… We also work with many other forces that are somehow confronting many of these extensions. So, the question is very good. I think it’s a question for our society, at large, not only for us. And, in my opinion, it also is an ethical challenge that we all share. How do we put in place limits? How do we gain agency in what necessarily becomes an ecosystem of guilt in which also we participate?

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.