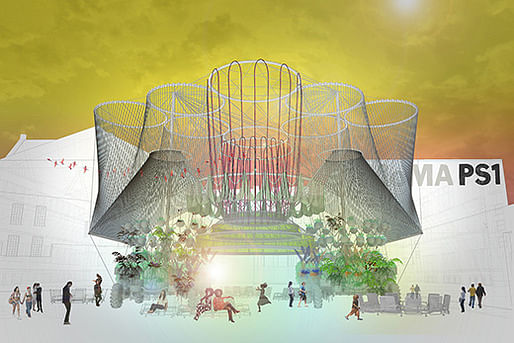

This Tuesday, the eagerly-awaited, annual Warm Up series of concerts and events will launch beneath the orbicular forms of COSMO, the winning entry of this year’s MoMA PS1 Young Architect’s Program competition. Designed by Andrés Jacque / the Office for Political Innovation, COSMO is not just a pavilion but also a complex water filtration system. Archinect got in touch with Andrés Jaque to talk about the process behind the design as well as his hopes for its impact, both locally and abroad.

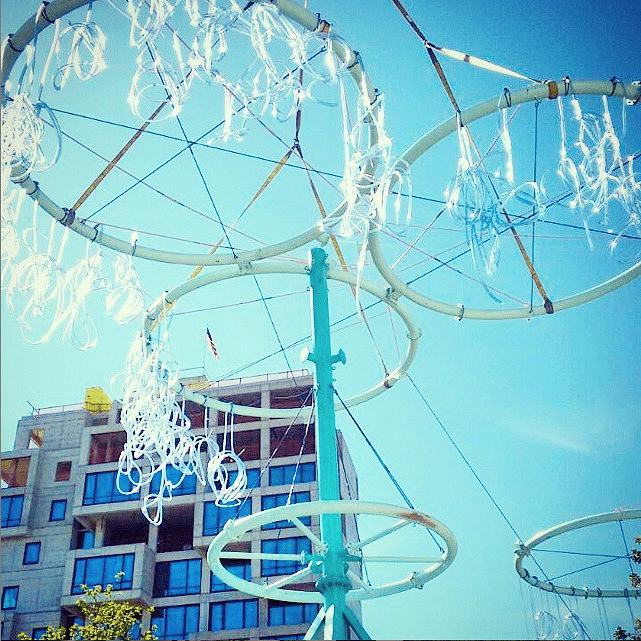

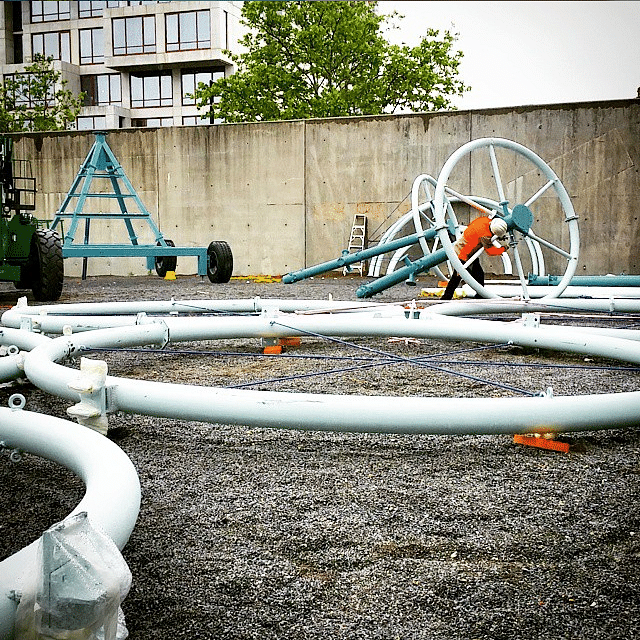

Earlier this year, Jaque joined us on Archinect Sessions to discuss COSMO. The moveable structure is constructed out of custom-designed irrigation pipes, and seeks “to make visible and enjoyable the so-far hidden urbanism of pipes we live by.” Over the course of the installation, some 3,000 gallons of water will pass through a series of filtration systems, becoming increasingly purified as it cycles.

This year marks the 16th iteration of the Young Architect’s Program, which gives emerging practices the ability to imagine innovative designs for the courtyard of MoMA PS1. Entries must satisfy a series of criteria, including providing shelter from the sweltering New York heat as well as seating for concert-goers. COSMO continues threads from last year’s installation “Hi-Fy,” fostering conversations about pressing ecological issues and their relationship to architecture.

We’re getting close to the opening of your installation for PS1. How has this process been? Has the project changed over the course of its development and materialization?

COSMO is not an icon or a fixed object, but a working assemblage of diverse technologies and ecosystems, adaptable to evolving external conditions. The contingencies of something that has to be working in a limited time are not that different to the ones that the weather or the evolution of pollution poses. COSMO is not an icon or a fixed object

We have also worked with many groups of people that have been dealing with the quality of water and water bodies in NY for decades, and their participation has had a great effect making the project more accurate in its ecosystemical design.

You’ve been quoted saying, “Architecture is always a political action.” What are you expectations for the possible political effects or reverberations in the immediate context of the installation, ie. Queens and the greater New York City metropolitan area?

There is already a great attention to the way COSMO proposes to think of water infrastructures. There is a possibility of decentralizing them, to make them readable by people, and to think of them as spaces to inhabit. That is different from the way infrastructures are usually constructed and experienced. To make this alternative infrastructural thinking , one that can be collectively considered, the infrastructure must be made accessible. That is what COSMO seeks to deliver.

PS1 Young Architect’s Program is a highly-visible event within the international architecture community. How would you like COSMO to be read from afar?

My impression is that culture is no longer happening in isolated cities but in networks that cross and connect different locations. It is true that COSMO went viral and had a great impact online, but for us the challenge is to make sure that energy and that interactive capital is mobilized by a relevant discussion, that instigates progressive ways of relating to plumbing.

culture is no longer happening in isolated cities but in networks that cross and connect different locations

COSMO comprises an intricate water filtration system. Is the technology that you and your team have developed repeatable in other contexts? Or does its socio-political efficacy primarily emerge semiotically, which is to say, in the capacity for architecture to gesture towards something else – in this case, the global water crisis?

It is both. On the one hand, COSMO does treat water, turning polluted water potable. But never the less, its function is to make that process transparent so water treatment becomes an issue. We are used to the way the readability of cities and their functioning remains segregated; our proposal is precisely to bring these two realms together as a way to make them more enjoyable and bring awareness to their users. COSMO’s goal is to contribute to increasing awareness-based citizenship.

Could you explain some of the technical aspects of the water filtration system?

The system is composed of four ecosystems, and the water circulates through them. The first one is a group of aerobic tanks, then sedimentation, mechanical filtration and finally chemical decomposition, with an outcome similar to that of a wetland. From the tanks, the water will be pumped into 40 circuits of clear tubes, in which the effect of UV rays will minimize the presence of bacteria in the water. Then to an algae bag, where its levels of nitrogen and phosphates will be balanced. Finally the water will fall through a scrubber, that will increase its levels of diluted oxygen, and then back to the tanks. COSMO’s goal is to contribute to increasing awareness-based citizenship.

In an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, you discussed working as an architect in the midst of a “crisis of expertise.” How has the role of the architect changed in an era marked by both new technologies as well as overlapping environmental, economic, and social crises? To what extent do you think the architect(s) is beholden to address these issues?

Even though we know it does not work, we still tolerate the idea of architects as masters illuminating the masses. When we look in detail at the way the urban is daily performed, we can see that architects are not the only ones treasuring urban intelligence , but mediators operating between a great numbers of actors and networks that possess specific forms of urban intelligence. Activisms, plural intelligences, and the experience of affected people and resources are as important voices as those of official experts.

With projects like IKEA Disobedients, the Office for Political Innovation seems to go after the politics that govern architecture as a specific field. To what extent do you see your work as fighting against the “architecture of architecture,” the implicit rules that govern what architecture can be and do?

IKEA is the most powerful architectural actor nowadays. It distributes every year more than 200 million copies of its catalogue in 29 different languages. Twice the global distribution of the bible. It invests great efforts on describing and therefore promoting daily life as a familiar existence, inhabiting perpetually sunny Saturday domestic interiors. There is no need to say that is a very ideological way of promoting daily life.

Activisms, plural intelligences, and the experience of affected people and resources are as important voices as those of official experts.

I believe that the architect’s role nowadays can also be providing alternatives, and enriching through diversity the collective catalogue of desirable possibilities. Projects we developed, such as the House in Never Never Land, the Escaravox or the Plasencia Clergy House were intended to do that.

Who are the figures – historical and/or contemporary – that you consider your most important allies? That is to say: who do you work with? who are you reading? whose work do you draw inspiration from?

The domestic innovation by Rudolph Schindler and Pauline Gibling in Southern California [the MAK Center], the technology for change by Albert Frey’s first own house in Palm Springs, Cedric Price, specially his temporary works for the Sheffield Festival, Lina Bo Bardi and her involvement with existing communities in SESC Pompéia, the performance of the New York Public Library...

Finally, what’s next for the Office for Political Innovation?

We are working now with Patrick Craine in the development of what we call a performative residence in an exceptional geographical location close to Corpus Christi, Texas.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

3 Comments

According to Patrik Schumacher architecture is not political.

I don't think this qualifies as architecture, but it's very interesting. Looks like jelly fish.

Being a construction methods dork, I want to point out that the sight of these images remind me of the piece A Room by Sopheap Pich, also a large ring with things hanging from it, which I helped install. It's not simple doing this kind of work. COSMO looks like it's coming together really well!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.