On the episode “Family of Six Goes Tiny” of HGTV’s Tiny House Hunters, Cindy, Dan, and their four daughters, ranging in age from 14 to two, downsize from their 2,500 square foot house in Santa Clarita to a 600 square foot home in Corning, New York—100 square feet per person. The real estate agent thinks they’re insane. What motivates such an extreme move? Debt aversion, in part.

Unlike most HGTV shows, where no mention is made of financing, Tiny House Hunters is chock full of people expressedly trying to avoid taking on debt. In fact, the tiny house ‘movement’, in general, has a strong connection to debt aversion. “While we don’t think tiny houses are for everyone,” write the authors behind thetinylife.com, “there are lessons to be learned and applied in order to escape the cycle of debt in which almost 70% of Americans are trapped.” Brad Allan, a Massachusetts-born tiny homeowner tells USA Today, “I guess my main goal in living this type of lifestyle is to not have a lot of debt."HGTV is both a reflection of, and an agent in, the construction of homeownership as a normative ideal

Both Tiny House Hunters and the trend it depicts have a strong connection to the 2007-8 financial crisis. In 2009, a marked shift occurred in the channel’s programming. While previously the channel had, notoriously, valorized homeownership as an attainable ideal, afterwards, to align with the depressed economy, they began to screen (some) shows that were more attuned to the financial realities of its viewers. Actually, following the crash, some commentators had gone so far as to blame the channel for fueling the housing bubble. “The cable network HGTV is the real villain of the economic meltdown,” Jim Sollisch wrote in the Wall Street Journal. This is, of course, ridiculous. Neither the television channel nor its viewers—those who took on, without adequate guidance, subprime mortgages—were responsible for the crash. But there is a relationship here.

HGTV is both a reflection of, and an agent in, the construction of homeownership as a normative ideal. That is to say, a place of one’s own is pinned to the top of most people’s vision board, whether they know it or not. And this desire is, in part, artificially inculcated to help fuel the housing market, which is central to the contemporary economic order. According to media theorist Shawn Shimpach, HGTV is complicit with the political economy of neoliberal capitalism in a variety of ways, most notably as a mechanism for the production and enforcement of an “ideology of domesticity”. “The programming on HGTV has always and continues to simply presume the normality of homeownership and then repeat it ad infinitum,” he writes. “The programming thus normalizes, routinizes, and naturalizes the facts and practices of investing in domestic property, by displaying and narrativizing, through sheer repetitive volume. It allows the ideology of domesticity to not simply underlie the commercial programming but to be visualized, made accessible, imaginable, and desirable, associating home with comfort and achievement, on the one hand, and with labor and investment, on the other.”

In other words, the channel makes homeownership seem normal and achievable for a broad swath of people whose wages aren’t actually high enough, or stable enough, to afford (overvalued) property. Notably, this swath cuts across class, race, and sexual differences more than the vast majority of television produced in the United States. Everyone wants an ‘open concept kitchen’ and, somehow, everyone can afford one. Historical differences and conflicts are erased by the utopia presented in homeownership while, in reality, they are enforced and exacerbated by the mechanism enabling widespread homeownership: subprime mortgages. “Low-income and racially marginalized neighborhoods, once redlined and excluded from mainstream credit markets, were at the center of the profitable wave of subprime abuse and equity extraction during the long housing boom, and are now at the center of the long, slowly unfolding catastrophe of the U.S. foreclosure crisis,” write Jeff Crump, Kathe Newman, Eric S. Belsky, Phil Ashton, David H. Kaplan, Daniel J. Hammel, and Elvin Wyly (2008).what you watch affects the way you live

Moreover, the shows serve to train the viewer in matters of taste and self-discipline. DIY’ing may be fun, but it’s still labor that requires logging some hours of training. Here the home is seen as an asset worth investing not just your money into but also your time. In the process, these shows create a homogenous interior aesthetic that stretches broadly across geographies and class while, pivotally, blurring “the distinctions between self-expression and the ‘financialization of daily life’”—or, basically, the process by which neoliberal governance and ideology make everything about money. Redecorating is both what one wants to do and what one should do. It’s not just fun, it’s smart business. And the more disciplined you are—painting your own walls, adhering to design templates—the better you are (as a homeowner, a debtor, a person).

That is to say, what you watch affects the way you live. It structures your desires and your habits, even as you incorporate the consumption itself into your daily schedule. But the relationship runs deeper: when millions of people watch media that constructs and instructs a particular image of domesticity, the adoption of that image as a lifestyle has economic, social and political ramifications. When a vision of home as an 'investment' gets drilled into your head, it’s hard not to think of it as one—and to idealize its potential. When those (fragilely-held) investments are bundled together and traded at high speeds by professional investors, the world economy changes—and so does governance, which both enables and responds to this new ideology of domesticity. Of course, when this economy swells, like a soap bubble, new shows are made to reflect it. So the bubble grows and grows until the belief in the solidity of those investments, of that vision of domesticity, shatters. And, when it does, you suddenly find yourself without a home at all.

This is, of course, a highly reductive image of the 2007-8 financial crash. The relationship between television and the subprime mortgage crisis isn’t, at all, chicken-and-egg. First came the deregulation necessary to securitize mortgages. Television shows represented the cultural and ideological shift that accompanied these economic changes. But, in representing it, they also helped enforce the new paradigm. Lifestyles are branded things and images of domesticity spread like memes. They proliferate, become adopted by others, and proliferate further. Alongside media representations, we also participate in selling the way we live to others, presenting our consumptive patterns as demonstrative of happiness, coolness, or, perhaps most insidiously, normalcy.images of domesticity spread like memes

Tiny House Hunters is at once a reaction to the mechanism that enabled the housing boom—debt or, specifically, subprime mortgages—and a symptom of the survival of the image of domesticity that underpins it. Of course, the majority of people have been living in small accommodations—or small by contemporary, U.S. American standards—for longer than they’ve been living in McMansions. But, in a country where bigger tends to be viewed as better, tiny houses stray from the norm. At the same time, they represent the persistent fortitude and appeal of the ideal of homeownership despite the clear repercussions it had for the millions of Americans who found themselves unable to pay back loans they were never prepared to take on in the first place. To maintain the American Dream post-2008—both a home of your own and financial solvency—requires some compromises. After all, you can’t have your cake and eat it too. (Or most people can’t, at least.)

In other words, tiny homes are a statement as much as a form of shelter. In a culture that centers homeownership as an indicator of success, size almost always matters. ‘Curb appeal’ means, essentially, ‘curb speak’: the ability for your home to demonstrate to the local neighborhood the solidity and vitality of the people it shelters. Bigger homes are associated with wealth; an unmanicured garden signifies neglect, and therefore economic, social, or even mental troubles. But with tiny homes, the statement made is a bit more complex. You’re still signifying a type of wealth, but one that runs diametrically opposite to the financial paradigm of the era. Here, freedom from debt is the highest prize. And tiny homeowners often want to yell it from their tiny roofs.

Maybe the first person to radically downsize their living accommodations to prove a point was the philosopher Diogenes. The cynic—or more accurately kynic, which is something of an antonym to the current definition of ‘cynic’—lived in a large ceramic jar with his dog in the center of the city. Practicing his philosophy rather than merely preaching it, Diogenes would masturbate and defecate in public; he ridiculed Plato, Socrates and Alexander the Great. He was known to carry a lamp in daylight, ‘in search of an honest man’. Through his actions, Diogenes subverted the norms of Athenian society—their rigid adherence to respectability. “In a culture in which hardened idealisms make lies into a form of living,” writes Peter Sloterdijk of Diogenes, “the process of truth depends on whether people can be found who are aggressive and free (‘shameless’) enough to speak the truth.”

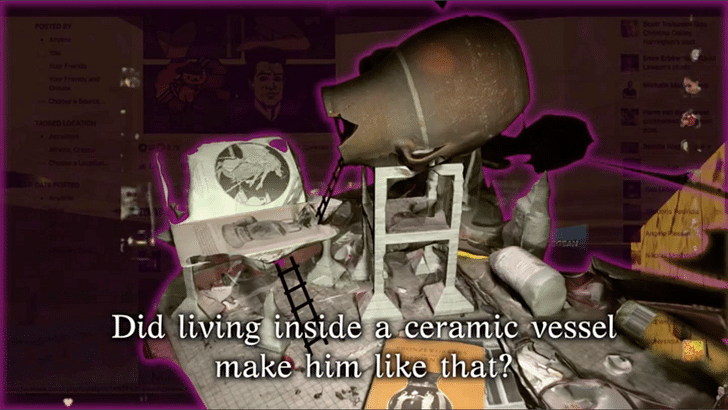

The architect Andreas Angelidakis’ 2016 video Vessels is concerned with the transmission of ideas and images of architecture over time, comparing the pottery of Ancient Greece to our social media feeds today. “If you look around Europe today,” the narration goes. “It looks like the information that Ancient Greece exported registered in the form of buildings. Neoclassical remakes of Ancient Greek Architecture. Did the vessel carry this information abroad? Were the pots encrypted with secret building components to slyly affect the architecture of faraway places? Could the painted vessels have been buildings in disguise? And would those buildings continue to transmit information?”

Lifestyles are inherited, and these inheritances are issued, in part, intentionally

The video also discusses Diogenes—“the only person I know who lived inside a pot next to his dog in the marketplace." Did living in the pot turn Diogenes into the man who “trolled” Plato and Alexander the Great, or did his house turn into a pot in response to his behavior? In short, Vessels questions the way that we come to live as we do. Lifestyles are inherited, and these inheritances are issued, in part, intentionally. Moreover, ideas of domesticity, of architecture, come through images. By living in a pot, Diogenes manufactures an image of domesticity in reaction to the lifestyles of his contemporary. His life constitutes a form of criticism, all the stronger in that it is acted out rather than merely spoken. Through negation, he shows the absurdity, and artifice, of how his fellow Athenians live—their grand villas on the edge of town, feinting isolation from the marketplace.

Are tiny homes the pots of today? Are tiny homeowners the Diogenes of the 21st century? Their lifestyle, a hyperbolic negation of some of the dominant values that define contemporary domesticity, draw attention to the absurdity of our normalcy. They show that our ideals are far from natural, but rather constructions with very real implications: a life of debt bondage. Yet these tiny homeowners remain beholden to the foundation of our “ideology of domesticity” in that they are oriented towards a false sense of economic autonomy made manifest through property deeds. Moreover, while their lifestyles are reactive, they can’t be said to really constitute criticism in themselves. Still, tiny homeowners, or, more precisely, Tiny House Hunters, provides a model that can be detourned to serve alternative purposes. If ways of living are contagious and constructed, then hyperbolic, practiced representations of our current ways of living might just point to the artificiality of our precarity. And maybe, just maybe, such images of cynical lifestyles could change things.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

6 Comments

This is the headiest article about tiny houses that I've ever read. I think a lot of the concepts presented by the author ring true, but I also think there's an easier way of saying "tiny houses are gaining in popularity because houses are expensive and people don't have enough money". <--- Oh look, I just said it! Seriously though, tiny houses are fun. Thanks for the perspective.

So let's spend 50-75K on a glorified trailer and then still spend money to lease a spot every month! Yay!

Idiots.

Okay, heady perhaps...but explaining some very good points and some interesting history. It has always confused me that the "tiny house phenomenon" has been called a movement. It does seems to me that it's more of an indicator of where people's heads are at. I'm all for rethinking and bucking the norms whenever possible! Thank you for providing so much insight into this issue.

Also I didn't see any way to find the video of Andreas Angelidakis Vessels. Can you suggest any way to find that? Sorry if I missed something you already included.

dirk

Hey Dirk, Vessels premiered last year at the Liverpool Biennial. Unfortunately, Andreas hasn't yet released it publicly, although he often does release his videos on Youtube. I'll check with him to see if he has any plans to — in the meantime, I highly recommend taking a look at his channel!

Thanks Nicholas! I will. I already looked at his archinect page and it is great. - cheers, dirk

Not that it's central to the article but why Corning NY of all places?

It's not a hot spot for just about anything save for a cool museum with a fantastic addition (and the company headquarters- which are small). Regionally speaking, Corning is just at the edge of being part of a number of bedroom communities that serve Cornell. But here's the twist- historically these communities serve staff and not faculty for the most part because property values are so low. You can buy a reasonable house for a third of the price- excluding the commute.

So why build so small in such a depressed market?

And "this has already been done" on 17/ soon to be 86. Two students as SUNY B built a home in Endicott instead of living on campus. They did it because they had little cash and it was an investment. The opposite of the family on TV.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.