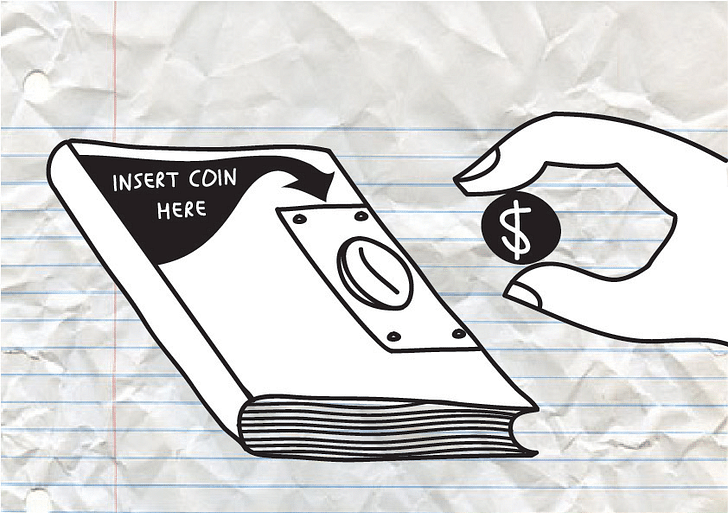

Do you know anyone who is not a debtor, at least in some sense? The idea is practically unthinkable. To participate in modern life, one must take on debt: credit cards, housing loans, medical bills, education. Even cash is a form of debt, albeit normalized to the point that we no longer think of it as such. State of Debt and the Price of Architecture is a series that attempts to consider the particular situation of architecture student debt within a larger cultural and historical framework: to show just how strange (and untenable) the normal actually is.

In his book Debt: the First 5,000 Years, the anthropologist David Graeber formulates a history of debt, arguing that it actually preceded bartering and currency-based transactions. The current global political-economic system is a complex network of debt, largely in the form of deficit spending. Sometimes, like in the case of Madagascar, former colonies are still paying for infrastructure projects they never asked for. Other countries are still paying reparations for wars fought by men now long dead. The International Monetary Fund is a debt-collecting agency that enforces the debtor-status of Third World countries, often to devastating effects such as with Argentina at the turn of the last century or Greece in the last decade.

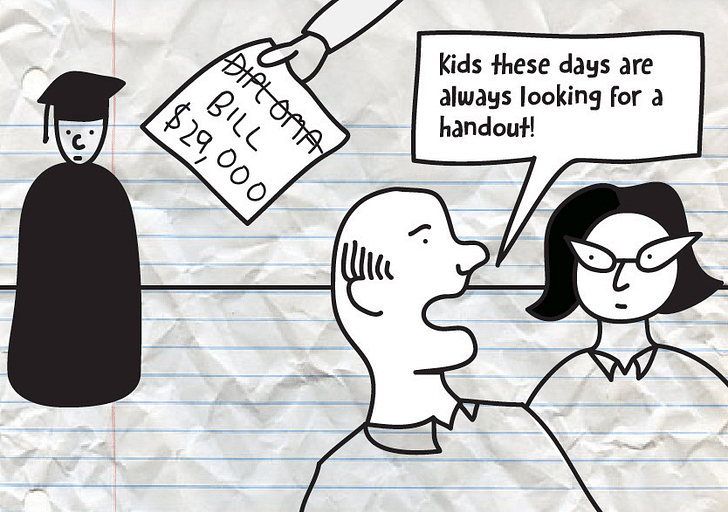

On the other hand, Graeber notes that debt is a flexible, abstract concept. After all, it has become equated with vague moral standards that seem synonymous with shame or guilt. This guilt, however, seems to be disproportionately distributed. The United States holds more foreign debt than all Third World countries combined, but austerity does not descend on these shores because of maintained political hegemony. Those in positions of power tend to be able to use debt to their advantage, while marginalized populations tend to be forced into financial obligations out of necessity, which often comes with a strange, condescending assumption of guiltiness. Graeber writes, “For most of human history – at least, the history of states and empires – most human beings have been told that they are debtors.” Through this system, empires have been able to maintain dominion over populations as well as striated class relations. When the debt becomes too great, or the conditions for failure to repay one’s debt become too severe (think debtors’ prisons in the 19th century) a backlash inevitably ensues. The historical record, from Rome to today, is replete with subtle measures that soften the mechanics of debt, usually as attempts to avert large-scale unrest. When these efforts don’t pan out, some kind of violence tends to erupt.

Debt is a flexible, abstract concept.

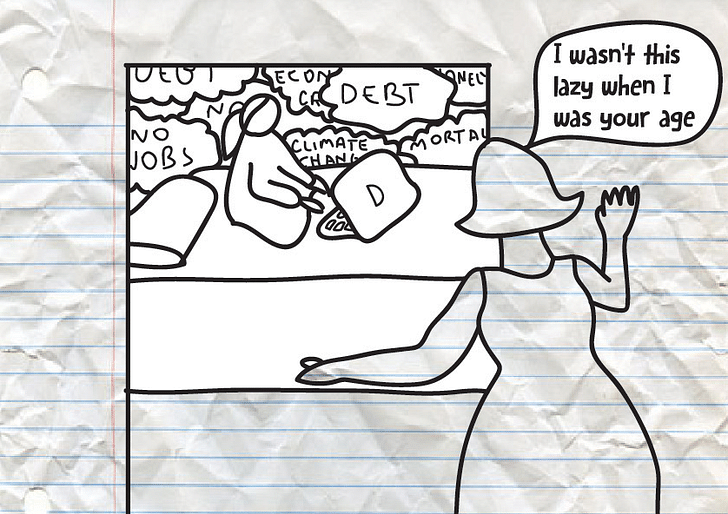

Within the larger network of debt relations, student debt stands out as particularly insidious. This is because the situation is, in many ways, unprecedented: first, because higher education has never been available to this extent to the general population; second, because never before has the expectation to attend university, and even postgraduate programs, been so widespread; third, because the costs of this now-mandatory education have sky-rocketed over the past few decades for a number of reasons, not least of which is that universities have increasingly took on the form of for-profit corporations. Yes, a young American has the choice to not attend a university. But that is a very limiting choice to make at a young age – almost as limiting as taking on hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of loans.

One’s credit score could alternatively be called one’s public worth as well as one’s freedom quotient.

But what does this mean, on the ground?

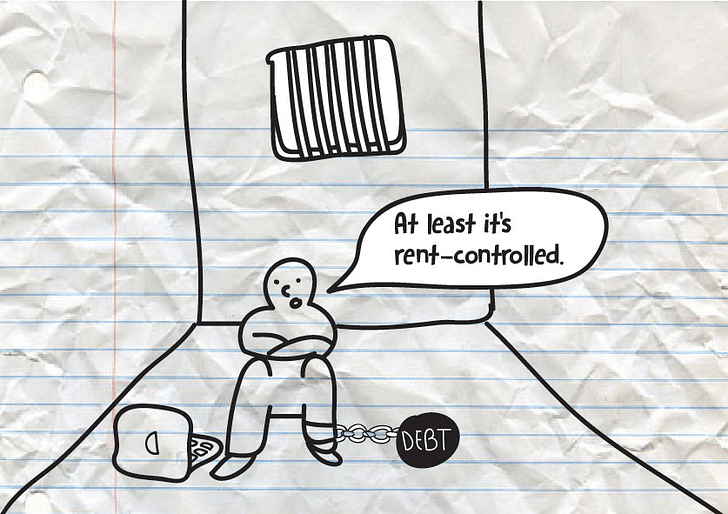

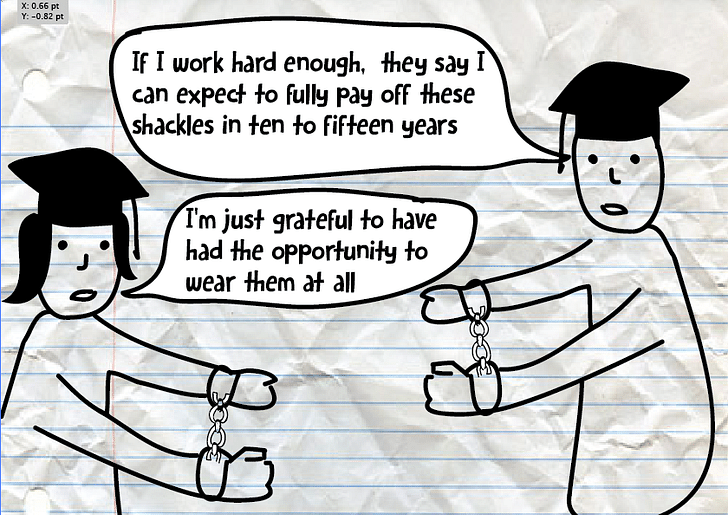

In order to become educated – whether as an academic, artist, tradesperson, architect – chances are you will have to take on some doubt. This means in order to be educated, to be able to work, you must take on a long-term relationship of dependence to an institution. Taking out loans means that the longer it takes you to pay the institutions back, the more expensive it will be over the long haul. Like a 19th century indentured servant, a young architecture school graduate owes her time not to the profession or to herself but first and foremost to a lending institution. Her decisions – professional, but also aesthetic, formal, etc. – must take this relationship into account in some way, and therefore are not entirely her own. Moreover, by having made the decision as a young woman to attend a university, she entered into a sort of slavery, in which she must consistently work for the foreseeable future or else damage, perhaps irreparably, her credit score. One’s credit score could alternatively be called one’s public worth as well as one’s freedom quotient. It’s a strange bind: devote yourself to paying off your debt or have your freedom severely limited by defaulting. And this doesn’t even account for the other debts one takes on if they want to start their own firm, for example.

In his book, Graeber pays close attention to a strange historical precedent for debt relief. In ancient Abrahamic tradition, every fifty years there would be what was called a “Jubilee,” or an event of mass debt-forgiveness (among other merciful acts). Essentially, a Jubilee leveled the playing field, disrupting the potential for extreme financial disparity. Graeber writes, “It seems to me that we are long overdue for some kind of Biblical-style Jubilee: one that would affect both international debt and consumer debt.” This is exactly the idea behind "Rolling Jubilee," a project “that buys debt for pennies on the dollar, but instead of collecting it, abolishes it.” Started by Strike Debt, an offshoot of Occupy Wall Street, the Rolling Jubilee legally buys chunks of debt and, using crowd-sourced funds, pays them off. Instead of the “shadowy” market of debt buyers that currently exists, the Rolling Jubilee makes no profit off the debts they buy. While valiant, this effort is far off from the large-scale Jubilee hoped for by Graeber.

Debt affects the graduate more than the student.

Rolling Jubilee is not specifically oriented around student debt nor around architecture, but any serious attempt to look at the way debt affects the profession has to also include a more general consideration of debt. After all, debt affects the student less than the graduate. And to run a firm almost automatically implies taking out some loans. This holistic perspective seems to be one of the general ideas behind the Architecture Lobby, a New York-based group “advocating for the value of architecture in the general public and for architectural work within the discipline.” Their approach includes a systematic reimagining of the profession, starting with demanding that architecture firms must pay living wages to young architects. Among other projects, they are initiating a program that entails firms pledging to pay their interns and, reciprocally, interns pledging they will only work for firms that pay. The Architecture Lobby joined Paul, Amelia, Donna and Ken recently for an episode of Archinect Sessions. If you haven’t already, listen in to find out more about Architecture Lobby’s work, like the time they almost got arrested in Chicago, or visit their website to get involved.

Before continuing with our questionnaires, we would first like to solicit personal stories about living with debt from our readers. Do you have something to say about the debts of your life? We want to hear about the good, the bad, and the ugly of becoming an architect. Get in touch via email, Twitter, or by phone: (213) 784 7421

How old are you?

24 years old

What's your nationality?

Venezuela/Spain

Where are you from?

Caracas, Venezuela

What is your prior educational background?

B.A. in Urban Studies, Vassar College

Do you have any debt that is not related to your architecture education?

No.

What is the total amount of debt you estimate that you will have after graduation?

Around $45,000

Have you received financial support from your family? Approximately what proportion of your total expenses?

Yes, about 1/3 of my educational fees are being covered by my family

Are your parents cosignatories on any of your loans?

No

Do you expect to be able to pay off your debt in the future? If so, when?

Yes, I expect to pay them within the next ten years or so

Does the amount of debt you’ll have after graduation affect how you envision your career?

No

Will your debt affect decisions like, for example, being in a smaller firm versus a more corporate firm?

Yes, probably

Have you considered alternative architectural business strategies or supplementary income to help bring down your debt?

The GSD is actually one of the few architecture schools that offers any sort of financial aid for international students, so while in school I'm working a side job at Harvard to help me cover costs of printing and materials, and a portion of my rent, in addition to the grants they have offered me

Student debt is an enormous issue in this country that limits the potential of new graduates and cripples their ability to make meaningful contributions to the profession.

How often do you think about your debt? How often do you talk about it with your friends, fellow students and/or family?

I think about my debt about twice a month. Usually when I have to pay bills of any sort that kind of opens the money conversation within me. And yes, we talk about debt openly.

Does your debt scare you? Keep you up at night? Do you ignore it? Broadly speaking, can you describe the emotions you experience when thinking about your debt?

It does scare me, especially as an international student that doesn't quite fully understand how the whole system works in this country. The sociopolitical and economic situation in Venezuela isn't the best either, so I took on most of this debt to release burden off my parents... so half of the time it's feelings of fear and anxiety and then the next day it feels like it's worth it. Rollercoaster of emotions.

Prior to studying architecture, were you familiar with typical architecture salaries? Do you think architects are underpaid?

Yes, I do think we need to advocate for better remuneration within the profession. And yes, I did my research before coming to school.

If you had known beforehand the amount of debt that your education would require for you to take on, would that have changed your decision to pursue architecture?

I was fully aware of the amount of debt that my decision to come to architecture school would represent.

Do you think the current reality of debt in architecture will affect the field in the long term? How?

Yes, definitely. Not only within the field but also at large. Student debt is an enormous issue in this country that limits the potential of new graduates and cripples their ability to make meaningful contributions to the profession. Graduate programs tend to be quite long, and the system is so broken in the architecture world that instead of dedicating time to thinking about new modes of practice and more equitable models of architectural engagement once we're out of school, young minds are fed directly into the corroding system to be able to pay enormous debt piles...

How old are you?

27

What's your nationality?

American

Where are you from?

N.E. Ohio

Where are you currently enrolled and for what degree?

University of Michigan - Taubman College, Master of Architecture

What is your prior educational background?

Miami University (of Ohio), Bachelor of Arts in Architecture

Do you have any debt that is not related to your architecture education?

No

What is the total amount of debt you estimate that you will have after graduation?

~$150,000

Have you received financial support from your family? Approximately what proportion of your total expenses?

Yes, but only 1-5%.

Are your parents cosignatories on any of your loans?

Yes.

Do you expect to be able to pay off your debt in the future? If so, when?

Yes, but it is going to be at least 20 years.

Does the amount of debt you’ll have after graduation affect how you envision your career?

Absolutely. I would love to volunteer for a year domestically or internationally, but it's simply not financially possible.

Will your debt affect decisions like, for example, being in a smaller firm versus a more corporate firm?

Not exactly. I have a desire to work in different scales of offices, and I will negotiate a fair and reasonable salary at either.

Have you considered alternative architectural business strategies or supplementary income to help bring down your debt?

I would like to turn a house or two, mostly for the experience and because I love working with tools.

How often do you think about your debt? How often do you talk about it with your friends, fellow students and/or family?

Every once in awhile it will come up in conversation, which isn't so bad because it is important to be reminded of responsibility. If I owe a friend money, I immediately repay them back ASAP. It's quite different with a 150K debt, but I see it more as an investment than anything else. Sure, I may have been able to buy a house with that money, but I would still be responsible for a mortgage.

I'm positive there are young architects out there who could have been truly avant garde given the freedom to take risks financially.

Does your debt scare you? Keep you up at night? Do you ignore it? Broadly speaking, can you describe the emotions you experience when thinking about your debt?

Sure, it can be scary, but I try not to dwell on it. Instead I think about how hard I work in graduate school - and remember how valuable my time is. Everyone has debt at all stages of their lives, so in a way we're not so different.

Prior to studying architecture, were you familiar with typical architecture salaries? Do you think architects are underpaid?

My father is an engineer, so I had a pretty good idea of compensation. I do know a few architects who are definitely underpaid for the sacrifices they make, which is sad because everyone should be paid what they are worth. Perks only go so far in life. I think architects need to start demanding to be compensated accordingly, which in turn should increase service fees.

If you had known beforehand the amount of debt that your education would require for you to take on, would that have changed your decision to pursue architecture?

Possibly, but even before undergrad, I was conscious that my decisions would require a long term commitment.

Do you think the current reality of debt in architecture will affect the field in the long term? How?

I'm positive there are young architects out there who could have been truly avant garde given the freedom to take risks financially. The size and structure of firms will likely be very different in the future, but technology will also be a major factor in that. If urbanization continues on the upward trend, the rules of economics will draw more young people to the profession. Whether or not more scholarships and grants are available to these students remains to be seen.

How old are you?

22

What's your nationality?

American

Where are you from?

Los Angeles, CA

Where are you currently enrolled and for what degree?

SCI-Arc, undergraduate.

What is your prior educational background?

One year at NYU.

Do you have any debt that is not related to your architecture education?

No prior debt. My NYU debt has luckily been paid off by now.

What is the total amount of debt you estimate that you will have after graduation?

$70,000

Have you received financial support from your family? Approximately what proportion of your total expenses?

Yes, I have received financial support from my family. So far, all.

Are your parents cosignatories on any of your loans?

Yes.

Does the amount of debt you’ll have after graduation affect how you envision your career?

I feel more pressure to jump into the work force immediately upon graduation ––– especially with the prospect of going to grad school.

Have you considered alternative architectural business strategies or supplementary income to help bring down your debt?

Not yet.

How often do you think about your debt? How often do you talk about it with your friends, fellow students and/or family?

All of the time.

Prior to studying architecture, were you familiar with typical architecture salaries? Do you think architects are underpaid?

Yes, I was familiar with the typical salaries. I think the typical starting salary for most architects is very low, unfortunately. Seems to be just enough for he/she to get by.

If you had known beforehand the amount of debt that your education would require for you to take on, would that have changed your decision to pursue architecture?

I am lucky enough to have the support of my family during my undergraduate education, so a big weight has been lifted off of my shoulders.

Do you think the current reality of debt in architecture will affect the field in the long term? How?

No and yes. No, because I have noticed that the majority of incoming undergraduates are coming straight from high school, therefore most have the financial support of their families (as I have independently surveyed). In that regard, I think the field will be fine. However, as Masters Degrees have become very important and highly regarded in the field, the need and decision to go to grad school might be a game changer. It is really unfortunate that we have to pay so much for this part of our education. We all need to move to Europe.

Thanks again to our anonymous participants!

Want to get involved? Get in touch: email, Twitter, or by phone: (213) 784 7421

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

21 Comments

so everyone is cool with their student debt?

everyone is cool with becoming a 2nd class citizen in the hopes of thinking your education would make you a 1st class citizen?

everyone has accepted student debt as a national standard for becoming more intelligent and happy with your circumstances?

is anyone paying attention to the shit you got dragged into?

pink floyd and frank lloyd would not be proud of any of you!

it's not a handout to be scammed into a standard requirement and to ask for forgiveness for doing your duty once you get shat on.

another way to think of it, let's say you went off to Afghanistan to fight a war that you have nothing to do with for a good deal on a college education. you get back and realize the system you were trying to have an education in is so FUCKED up you don'' want that education anymore, but you go ahead with it. you nearly complete your undergrad and you realize the deal has ran dry, you have to pay to finish with some masters in absolute bullshit while your neighbor who drink beer after every hard days work as a union something makes twice your salary.

you liberal intelligence has made you a prime target for unfair trade deals.

well said^

and this is precisely why "certifications and licenses and all the other merit badges that are being sold and required are preventing a more informal and free system of self/peer education.

Olaf, when you were 20 years old did you seriously have a realistic understanding of what a large debt would mean once you got into the working world? If so you were a lot more sophisticated than I or any of my friends from school.

I'm not saying you're wrong, I'm saying you needn't be so harsh about it. This article and discussions here will hopefully help young kids - which college freshman are - have a better understanding that they should proceed with caution.

oh, didnt read that well, I mostly disagree with olaf. debt is pushed like heroin

Nicholas points out that "Debt is a flexible, abstract concept" and affects the graduate more than the student. Heroin is not a recreational drug and when your parents spoke to you in harsh terms about heroin you listened or you didn't and found out the hard way. Jla-x you read it right the first time. Your liberal intelligence is being preyed on by debt dealers. You trade your freedom and peace of mind for opportunity you may never get. When do you want reality to be harsh, now or later? (Olaf was also angry no one had posted anything yet on this very important topic)

An essential concept for understanding economics:

Money as Debt

ok, guess I was overthinking it. The kicker is that learning is free. education is probably the the least sellable thing since every bit of info paid for can be attained for free. We need to teach people to learn rather than seek degrees. we need to recognise informally attained knowledge and decrease this emphasis on degrees. my opinion

Olaf, should people unable to pay for their undergraduate/graduate educations in cash simply give up on the idea of higher education? This seems unbelievably short sighted unless you think education itself is a waste of time. Although, from the way you've argued in your posts, I imagine you've found a silver bullet to first class citizenry.

Isn't it more productive to discuss how we finance and pursue education rather than simply condescend to those currently in debt?

this entire society is held together by dreams. When society stops dreaming they stop behaving like good consumers. The elite want to keep us poor in the waking life and rich in dreamland. they want us to share their values while living an a parrallel reality so that we can continue to vote and act against our own interests.

Justin I think Jla-x is the only one who understands where Olaf is coming from and what he is really saying. See Jla-x post above............................... Well let's discuss it then 'how to finance and pursue education'............................ Right now your main options are loans, military service, scholarships and grants or cash. This means for most of us who do not get into Princeton as a legacy (cash from mommy and daddy) or on full scholarship for being really damn smart we will have to take out loans or do military service. I reference Princeton as it is one the Ivies that basically gives you a full ride if you are smart and poor enough................who was higher education meant for? Or why do you need it? Harvard (based on a study) says it's not for everyone and recommend most should invest in 2 year vocational tech schools for specific trades, but we 'culturally' insist we should all get a degree or go off and party for 4 years!! Even though more students have enrolled than when your grandparents who might have gone to college did, tuition has not gone down, but up and up and up! The Masters is the new Bachelors and there are more PhD students than possible dissertations! If the market is flooded with demand shouldn't the prices go down? So I ask you again who told you you should go to college and why? Why does the football coach make millions a year? College recruiters at big time schools make bank my friend. The system is to big too fail now, Olaf can't solve it here nor is he going to ask people to pay more taxes for serious students to party more...........................ok, but here we are, we got the degree and now we have to pay for it on the back end because we couldn't afford it on the front end. A 20 or 30 loan that doubles in its lifespan, but thank God for inflation, that $800 a month will feel like $100 in 15 yeas, but you have to pay NOW...........so here is my Olafs advice - take out more than you need senior year, like 20k extra from a private loan, dump it in stocks and mutual funds. Go into forbearance or delay repayment for a few years until employment looks good and take that $20k and buy a house and make sure car is already financed. Pay when needed on school loans and hope your house goes up in value over the next 10 or 15 years, refinance and pay off student debt.....or just claim bankruptcy immediately after school to rid yourself of credit card debt and private loans,in 7-10 years if you pay rent someone will offer you home mortgage - or sooner if you go for a No Doc loan (you may need up to 30 percent down) ..................oh wait, everything I suggest here is degenerate and risky and your debtors will ensure you feel like a criminal with plenty of anxiety. You judge those who have loaned you money as virtuous and fair. You believe they gave you an opportunity, to be fair they did somewhat. But most importantly you got the education of your dreams and now you feel it is only right to repay for the swindle................so Justin Halsey what do you suggest? You got the conversation going and I am sure Olaf has done nothing but further his condescending attitude towards those who were swindled (he isn't sure how that message came across).

JustinHalsey and Donna any suggestions? (Skip ramble discuss finance options)

The conditions you set out for pursuing a higher education:

be poor and brilliant, be rich, or go to a 2 year vocational school. Seems like you've made a lot of life decisions for children of working families who would like to pursue careers in fields that require skills the generation before us didn't even think about.

Would you prefer to live in a society that reserved higher education for a select few? I would prefer to deal with the complications of a diverse educational landscape available to as many as possible.

For better or worse, I fall into the camp of the believers in education. My education has propelled me into a professional life where I feel truly engaged. For this I feel lucky.

After your rambling seminar on money management (please, if you would, could you explain how compound interest works next?), I would suggest a couple education finance reforms:

No interest (at all) while in school

Interest rates equal to the Fed's on all student loans

No maximum for tax deductible student loan interest

The continuation of regulated repayment plans based on income

Eliminating the clause that taxes forgiven loan balances as income at the end of these regulated repayment plans

Hopefully these types of changes would cause a ripple effect - slightly more stringent lending, slightly more reasonable tuition to accommodate more stringent lending, few people in default.

I'm with you in criticizing the lenders and I certainly don't think my lenders were right, just, or altruistic in giving me an opportunity to pursue higher education. In my life, however, education has directly affected my mental, social, and professional life in an incredibly positive way. While I agree that not everyone in the world needs multiple higher education degrees, your economic status should not be the deciding factor.

Now we are getting somewhere, but you still ain't feeling the vibe of the ramble (George Carlin like observations of reality)......I think you add to payments based on income an adjustment for living expenses based on region. Maybe even an industry adjustment, for instance social workers get major adjustment which is made up by increasing interest on finance people, etc........You shouldn't be inspired to become a petroleum engineer in Wyoming because it will help you pay off your education quickly.......................Justin good stuff,any other proposals or takers?

As a six-figure indebted B.Arch graduate, thank you. Fortunately, I graduated into a good economy a few years back and have had some decent jobs that paid (fairly). This is a situation we need to continue to discuss, it is debilitating the spread of talent and decreasing our numbers as a profession. But what will the solution really be..?

On a (somewhat) related note to this quote "One’s credit score could alternatively be called one’s public worth as well as one’s freedom quotient." I recently read The Scoreboards Where You Can’t See Your Score re: "consumer-ranking" + "churn scores" and the new landscape of algorithmic reputation and optimization.

In terms of the question but forward by Justin about utility/social benefit of higher education couldn't agree more. Perhaps though the fix is as simple as free education for all who want it?

The basic reason for the problem is that easy access to large student loans guaranteed by outside parties makes it very easy for schools to charge tuition well beyond the potential value (in terms of future salary) for students.

if student loans were less widely available universities would need to compete on cost to attract all but the most privileged students. Alternately, schools themselves could be required to guarantee the loans - which would give schools a strong incentive to limit costs to something graduates could easily repay.

It might seem unfair at first because those wealthy students could easily afford to go anywhere - but realistically they are a small group who would have little influence on the broader market. Unlike for example real-estate, education is something even a very wealthy individual can only buy so much of - basically 2 semesters per year is the limit for everyone! Harvard and Yale might stay expensive, but you could be sure big universities would have to reduce costs to a level that the broad group of people who attend could afford.

Super interesting piece. It makes me think that the Architecture Salary Poll should collect student loan/debt information!

Nam, the best school model I know of is NYC's speciality high schools. Free tuition, competitive entry admissions. They are some of the very best high schools in the country and should be the basis for all higher education.

The idea that everyone should go to college is a fraud perpetrated by the corporate financial / for-profit university complex and slavingly used as a measure of "success" by high schools across the country. Occupational education is where the non-academic (dumb) kids are sent in high school. Meanwhile these programs as well as technical and trade schools produce people with employment skills ready to work productively in society.

As far as I am concerned, these kinds of programs should be mandatory for everyone. Wide experience is the hallmark of a good education.

NYT's The UpShot column recently examined current trends in student debt, asking has the crisis been solved? Specifically, as a result of two legislative tweaks (in last decade) to how federal student loan programs are structured

"We appear to be in the middle of a rapid transition in how student loans are repaid, one that is moving the federal government into the same role that state governments played for much of the 20th century: the foundational provider of broad, unqualified subsidies for higher learning".

Nam, the writer of that article thinks far better of the Income-Based repayment plan than I do. The example he gives is a generous one uncomplicated by major life events or even pay raises. I looked into it for myself and found the IBR could only screw me over in the long run. Running it through a calculator now based on my $60k of debt and $50k salary at graduation, it would have me paying $404.31/month for 25 years, totaling $121,293, ending in the oh so generous "forgiveness" of about $1,000. However if I just paid it back at standard flat repayment over the normal 10 year period, I would pay $683/month for a total of $81,938. That's right, IBR would cost me $40k. And then there's the complication that 4 years after graduation, I got married, and my partner's income renders me ineligible for the program, meaning that if I had tried to use IBR now I wouldn't be eligible but because I thought I would be at graduation, I would have spent 4 years letting my loans rack up an insane amount of interest that I'd have to pay off.

It's a nice idea, but there's definitely some real-world complications that don't seem to have been considered.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.