The Bartlett School of Architecture at University College London is consistently one of the most highly ranked architecture schools globally, and occupies a significant part of revolutionary educational history in the UK. Founded in 1826, UCL was the first English university to accept students regardless of religion, gender or social status, and was also the first to appoint a chair of architecture, in 1841.

The UCL Faculty of the Built Environment was named The Bartlett after its original benefactor, civil engineer Sir Herbert Bartlett, who played a part in many notable London structures at the turn of the 20th century. In its 175-year history, The Bartlett’s alumni (including the likes of Reyner Banham and ARCHIGRAM co-founder Sir Peter Cook) have made significant contributions to architectural discourse and theory, and its programming has continually adapted and expanded, now offered through a diversity of bachelor, graduate and postgrad-level degrees. On top of the School of Architecture, The Bartlett is host to 12 other schools and institutes devoted to the built environment, including the Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis, School of Construction and Project Management, Development of Planning Unit, School of Planning, and the Space Syntax Laboratory.

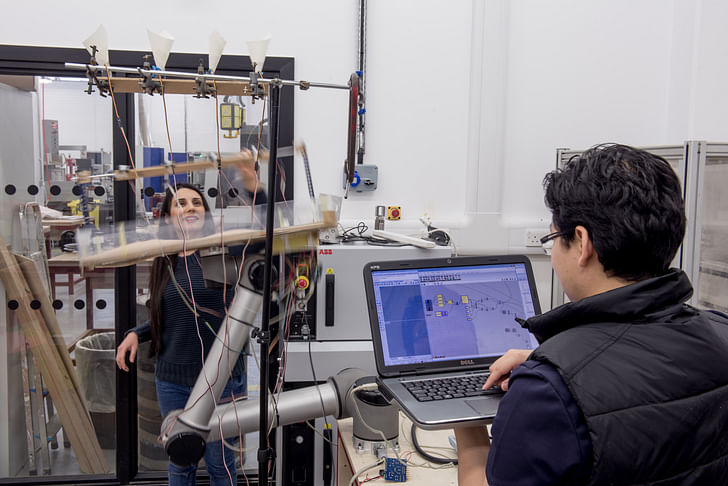

When architect, educator, critic, researcher and Bartlett alumnus Bob Sheil became director of the School of Architecture at the beginning of 2014, he was already firmly installed as the school’s Director of Technology and a Professor in Architecture and Design through Production. His strong connection to the the Bartlett’s experiments in technology and making fueled further investments in digital technologies at the school, when he founded the Digital Manufacturing Centre in 2009, which later became the Bartlett Manufacturing and Design Exchange (B-made). He is also an experimental designer as a founding partner of sixteen*(makers), and has been published and exhibited internationally.

Similar to the Bartlett’s academic tradition of continually expanding and complicating what constitutes the Faculty of the Built Environment, Sheil is invested in using the directorship to “open the school up to a broader audience.” I spoke with him this past July, shortly after the Brexit decision, about how he situates the school’s weighty history within the current architectural moment (and vice versa), and hopes for future architects.

What is your individual pedagogical stance towards architecture application, as it relates to the Bartlett?

I think my individual stance in terms of running the school is to nurture a culture of research-based education across all domains of our activity. And what I mean by that is, for students and staff to become acutely aware that architecture is a predominantly research-based subject, and the emphasis over the last five or six decades has often been about preparing graduates for the profession and playing the research game as a second fiddle. And the way in which this school is now blossoming is very much to position research in the foreground, and the graduate’s attributes for the profession are woven into that, but they are by no means dictated by that. So it still becomes a big laboratory, a work in progress that’s constantly looking at where our architecture is going, what it could be, what it has been. We see ourselves as one of the leading schools in the world that opens up new domains, new territories, new positions on what it means to practice, what it means to understand it and where we might take it. So my pedagogy is to nurture a culture of experimentation, of critical thinking and of design-less speculative production; really all those things together.

How would you distinguish the Bartlett’s programming from other architecture institutions, based on that pedagogical stance?

I think the first thing everyone notices about this school when they come here is the extraordinarily diverse range of positions it offers. So we have about 950 students now of whom 500 or so are on the professional programs and within that community, there are about nearly 28 different units or studios, which means that it’s really like a federation of all of these different positions. But the school is very famous of course for what Peter Cook and Christine Hawley did for us in the 1990s, in putting us on the international map and making us a very, very active player internationally as a place of design experimentation and critical thinking. And what we have done there is matured in those 25 years since into becoming a federation, really, a very established position. There is a lot of very high-profile staff now who have been here a long time, who in a sense run their studios like micro-schools, and what we do is we work a kind of chemistry between these various different we work a kind of chemistry between these various different studios, to create a school that’s constantly in flux.studios, to create a school that’s constantly in flux. [...] So rather than it being one big vision that leads this school, the impression everyone gets about it is this constellation of the diverse positions that are all very, very strong. That’s the first thing.

And the second thing that I think, for most people, is the very high level of production. Students produce huge quantities of work and in some ways too much, and this is something we are very aware of. Our students are obsessed with production and it’s nice to have that as a problem in a way but it actually is something that we are aware of as being something one needs to manage carefully, but it would just tell you how much enthusiasm you know everybody here has for the subject and the enthusiasm they have for education. And I think that this is something the school has—a really, really strong sense of making the most out of your time while you are a student.

Can you tell me a bit about some of the research projects currently going on at the school?

To begin with, one research project is led by Marcos Cruz. He was my predecessor. He is leading a project in bioreceptive concrete. It’s been funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council of the UK which is the Government’s Research Council for predominantly engineering and science-based things. It’s the first time the design arm of the faculty, which is the architecture school, has won a major grant from that Research a highly technical, highly specific piece of research coming out of a very arts-based and design-focused culture.Council and Marcos is bringing his sensibilities as a designer into the world of material science and digital production, and working in collaboration with lots of industry partners, such as Laing O'Rourke to develop a series of one-to-one prototypes for concrete panels, and that we have now here in our courtyard, growing all sorts of funny mosses and things on them. So that’s a really interesting example of a highly technical, highly specific piece of research coming out of a very arts-based and design-focused culture. And I think that trajectory is very strong. One often sees the arts and humanities running in parallel to the sciences, and they collaborate but they often just kind of run in parallel. But this is a project that’s emerged as a design and taken a leap into engineering and sciences, and offered something to that community that they haven’t envisioned themselves. So that’s quite exciting. That shows the kind of a trajectory the school is on right now which is very powerful. There are a few of those like that.

What kind of students do you feel are attracted to the Bartlett and why? What kind of student might flourish at the school?

It’s really hard to generalize. We’ve got at the moment I think 46 nationalities in the school of architecture. So you know that’s quite a broad range of backgrounds. We have students from different social mobility backgrounds, different economic backgrounds. I think the one thing they all have in common is they understand that particularly in the UK, the Bartlett is the Bartlett puts design as the number one focus of attentionuniquely at the forefront of design, research and design experimentation. I mean there are lots of good schools in Europe and in the world, but I think lots of people understand that the Bartlett puts design as the number one focus of attention. So everyone who applies to come there wants to participate in that. What they discover when they are here is that there is no manifesto for what that is. You know it’s a constant question. It’s a constant examination and what they enjoy about by being here is they understand they could find their own position in that time. So I suppose one further characteristic one might attribute to applicants coming here is they are quite driven. They have a strong appetite for design experimentation. They also want to find out who they are and why they are here. So when they emerge on the other end they’re graduates that are ready to launch themselves into the world.

What kind of services and provisions does the Bartlett have to help students find work after graduation?

We’re kind of spoiled in that regard because we are based in the center of London where it is a huge constellation of international consultancies and firms. We almost don’t do very much at all in terms of recruitment. I think 96% of our students had a job before the summer show opens. So the summer show each year isn’t so much students pitching to I actually think there is nobody better equipped than an architecture graduate to deal with Brexitthe audience at the show for work. The summer show becomes kind of bragging rights of employers turning up and going, well I’ve got these students over here, who have you got? So we are very fortunate to be located in London in that regard, but we are not complacent about this. And I think what we are noticing in recent years, students are looking much further afield. We are very aware that London is an expensive city to live in. So students don’t necessarily want to work in London. When they graduate, they want to travel further afield. So the school’s international outlook, the school’s international agenda sets them up very powerfully in that regard. They are going all over the place. They are going to the east; they are going to the west, the south, the north, Europe, everywhere. So there is a lot of that going on as well as the support one gets from London.

Do you foresee any potential shift in that, should the Brexit decision go through?

No one really knows what Brexit means, frankly, and nobody knew what it meant before the referendum and no one seems to know after the referendum either. My view frankly is that of all of the disciplines that are out there, architecture is the best place to deal with it because uncertainly and speculation is our core business. So I actually think there is nobody better equipped than an architecture graduate to deal with Brexit—because they’ve been dealing with uncertainty throughout their entire studies. You know, the very first crit a student goes to, they put a project up on the wall and everyone talks about it and reinvents it. And that’s from day 1. So students are used to this idea of the world being turned upside down in terms of their own views on it, their own projections into it. I think on a personal level though, you know if people are feeling a sense of some anxiety over what it might mean in terms of cultural relationships, we have already made it very clear that this school has a very, very clear, open international profile. We are certainly not a British school in that regard. We are an international school. I am not even British myself. So you know most of us here have got roots in other countries and you know we are going to fight very hard to make sure that that profile is maintained. And actually there is a very strong feeling now in the UK that Brexit won’t be anything like as dark as people made it out to be. It’s impossible to decouple this economy from Europe to that extent. We are too far in and the signal coming from the government right now is that it’s going to be a long process of realizing that it isn’t going to be a clear break. It is going to be a renegotiation of relationship.I think we feel we have earned a place in the top few schools in the world because we remain to be a curious school; we remain to be a school that reinvents the subject all the time

What kind of research and outlook do you maintain at the Bartlett to stay competitive with other schools in the market?

That’s interesting. We don’t think about it too much frankly. I mean I think if we all were worried about what the opposition were doing, we all start to mimic each other and it would all get kind of repetitive. So we know that there are a dozen super strong schools in the world and they are all good for a number of different things, and we feel we would like to remain in that kind of bracket on the basis of our continued production and design experimentation, and our contribution to what architecture is. So I think we feel we have earned a place in the top few schools in the world because we remain to be a curious school; we remain to be a school that reinvents the subject all the time, unlike the other great schools. And if we had a formula, you know I think we would drop off that list pretty quickly, and you just become a mediocre school where everyone knows what they do and it never changes.

So I think the thing that we feel, in the sense of awareness of the other schools, is what a small network we are and how every single school has links to other schools. There is no real pure isolated kind of faculty in any one school. We all have links. We’ve got great links to schools in the states and the same goes for Europe and Australia, South America and China.

What is the relationship between the school and London’s city government, and what kind of potential partnerships would you like to establish there?

That’s interesting. We don’t really have a direct relationship with London as a kind of authority, but as for the mayor in London, the main issues are housing and the economy and the finance sector, and housing is a kind of political hot potato, and that is an area that we hope is going to open up for us now as an arena to discuss the problems associated with housing in London.you have to have a very, very genuine dialogue with your students around their work

It’s not the right word to use, but one of the positive results with Brexit is that the housing crisis in London has become even more acutely an issue. So I think that would be probably the main one. We have links of course across London, but there are no formal links with the governance of the city, but looking ahead, I think it’s going to be focused more around housing. And in that regard, we made a number of appointments in recent years which we see as being bridge-building with the government on that issue.

How important do you think it is for a person in your leadership position at an architecture school to also be practicing architect, or to have practiced at one time?

I think it’s essential. I absolutely think it’s incredibly important even if—and it doesn’t mean it has to happen all the time—but I think directors of architecture schools most of the time ought to have that kind of background. But in the end when it comes to these kinds of decisions, of deciding who should take on these roles, it’s not always possible to hire someone with that kind of background because you have to hire the best candidate, and the best candidate can often come from a different background, history and theory or technology or something else. But it does, I think, work incredibly well if the school is led by people who have a very, very strong affinity with the school’s ethos and their own work. So Marcos [Cruz], for me, was very well known for being a highly experimental designer; Frederic [Migayrou] (who I work with very closely as the Chair of the school) is known for supporting very experimental design… So it’s not absolute, but I do think it helps an awful lot.

When the time comes for you to leave the deanship, what kind of overall changes would you hope to have made happen?

Well, I made this very clear when I started. I think the main thing I wanted to do was open the school up to a broader audience. So I felt very strongly about that because I have been here an awful long time. I was here before Peter Cook arrived actually. So I was a student. I just became a student a year before Peter Cook was appointed. So I’ve had an incredibly privileged experience being here as a student and then hired as a member staff and now I’m running the school. And I’ve seen more than a quarter of a century of the Bartlett in my lifetime. And I feel the one thing it had to do in the 1990s was, in a way, focus inwardly towards design as being its main agenda and as a result, it became quite obsessed with that agenda and that energy. And I think we’ve been a quite evidently successful school now for well over 15 years, and what I wanted to do is open that up to a much broader audience of the public, of all the professions and other kind of communities around the we just take their work incredibly seriously... and out of that comes a very matured, developed graduate.world and to be able to say well, yes, we are a very exciting school to work in and study in but what relevance do we have in the world? How is all of this energy and this production and this productivity and invention making a difference? So that would be my agenda, and I would hope that people would say that we did something in that direction while I was here, and I hope it carries on with whoever takes over.

How do you teach students to have a code of ethics in architectural practice and how do you form what that code of ethics might be?

That’s a really great question, and I think you have to do it in ways that are kind of relevant to the immediate experience. You can’t abstract it as some form of: “well in the real world, these are the issues you have to deal with,” and blah, blah, blah. But I think you have to have a very, very genuine dialogue with your students around their work, and if that is genuine and meaningful and they are producing work which they really buy into and are investing their own intellectual resources in, in a way that is drawing forward a real understanding of their role in the world as a designer and their role in the world as a researcher. That’s the point which you bring in the discussion about where those ideas could go, what they mean, how they resonate with other people and other participants.

What we don’t do here is put that to one side and then run a scenario of mimicking what the real world is like and saying, “Well in this sort of situation, these are the kind of the values one might want to consider.” We assume our students have a very high level of intelligence and ambition and can read into the conversation you are having with them about their work as being the kind of avenue towards understanding the world in which they might operate when they graduate. Otherwise you end up with this kind of peculiar way of the projects that go on inside the school are pretense, and that can never be—they don’t really relate to the ‘real world’. And the real world when you get to it is something quite unreal. So it’s about being genuine, and then you bring these conversations in in a very direct dialogue, in tutorials and crits and in lectures and so on, and tease out from students their own ambitions—what values they are putting into the work, giving them the space to breathe, the space to push the agendas of their work. Even writing the brief of their projects is an equation in itself that opens up questions of ethics and so forth. And we just take their work incredibly seriously—I think that’s how it works, and out of that comes a very matured, developed graduate.

The Deans List is an interview series with the leaders of architecture schools, worldwide. The series profiles the school’s programming, as defined by the head honcho—giving an invaluable perspective into the institution’s unique curriculum, faculty and academic environment.

For this issue, we spoke with Bob Sheil, Director of the School of Architecture at The Bartlett, Faculty of the Built Environment of University College London in England.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

1 Comment

Bob and Allen Penn's appointments have made the Bartlett THE most influential University in the UK. No comparisons. Bob's making background drives the school while Allen's vision of research Impact makes what goes on at the Bartlett relevant to challenges facing the world and profession. There is a clear vision set out to all that is implemented throughout the programme design, facility-resource scheme and staffing. You can see this on website with 2016-17 open letter to staff/students on website. Bob has a very hands-on approach to making certain this happens. Allen understands the structure of decision making in the University and makes it happen.

Went to the MArch G-AD shows in the last 2 weeks - while I think the work this year is slightly a lessor standard than the previous year(for reasons I won't go into), the work is an exceptional standard particularly when it compares to the many end of year shows I have attended in US schools including GSD where programmes are appropriated by a focus on professional criteria.

Well Done Bob and Bartlett staff / student.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.