“DESIGN EARTH is concerned with relationships between design and the Earth—as matter, scale, and worldview—to open aesthetic and political concerns for architecture and urbanism,” state El Hadi Jazairy and Rania Ghosn of their collective practice.

Founded in 2010, DESIGN EARTH emerged out of the duo’s experience working as editors for the journal New Geographies—a publication of Harvard Graduate School of Design, where they both received Doctor of Design degrees. The journal, which is still in publication, navigates a contemporary condition marked by large-scale problems that were previously outside of the purview of designers.

The idea that we have to redesign the Earth is the big question“Building on the journal’s agenda, we were interested in exploring how to re-examine our design tools and pursue a practice that plays the synthesis role that geography had aspired to play between the physical, the economic, and the representational,” Jazairy and Ghosn explain.

The name of their studio was borne out of an interview Jazairy and Ghosn conducted with Bruno Latour, the noted French philosopher. They asked Latour, whose work continues to influence their practice, to elaborate on his provocation to “rethink nature and the city” and its implications for design. “The idea that we have to redesign the Earth is the big question,” Latour responded. “We took him up on it!” they declare.

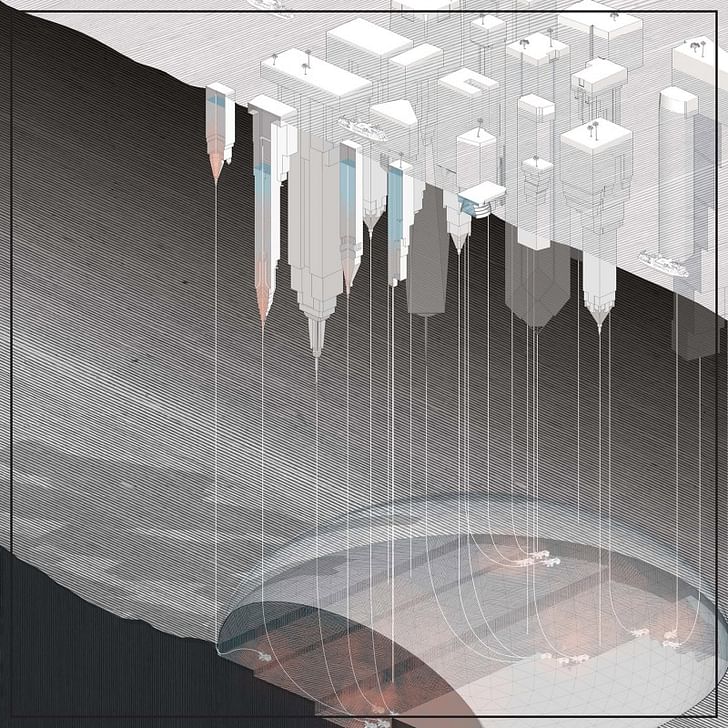

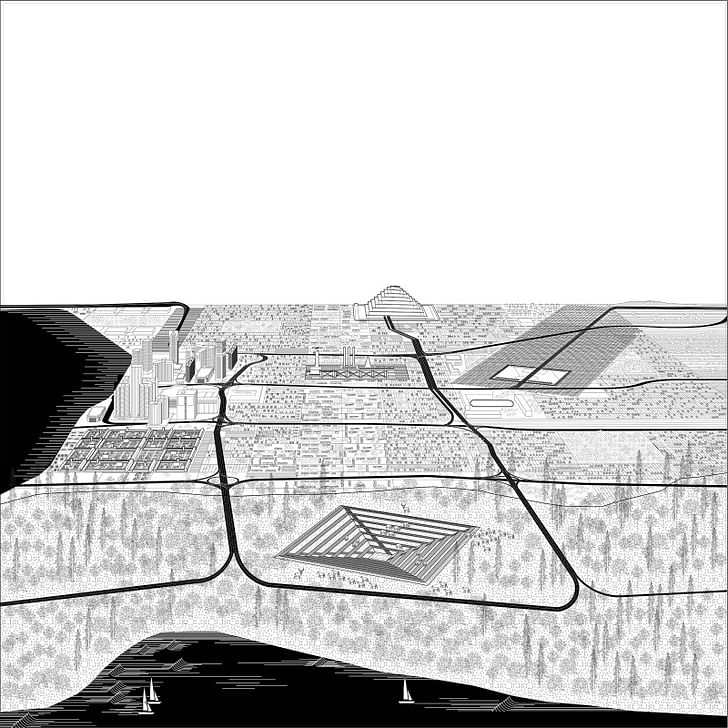

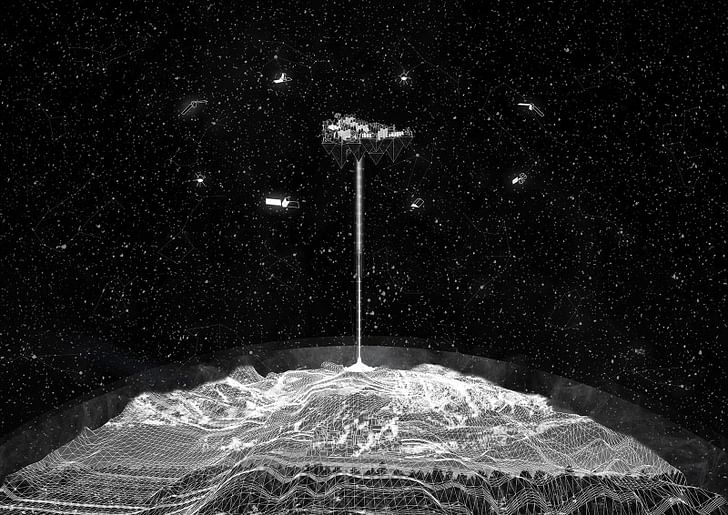

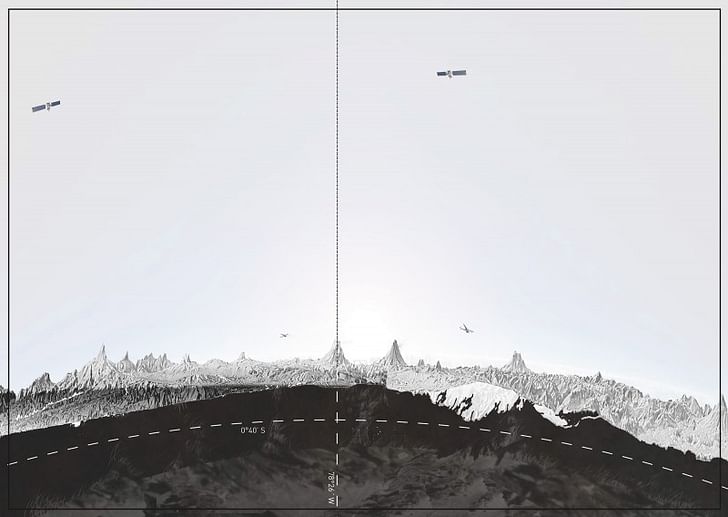

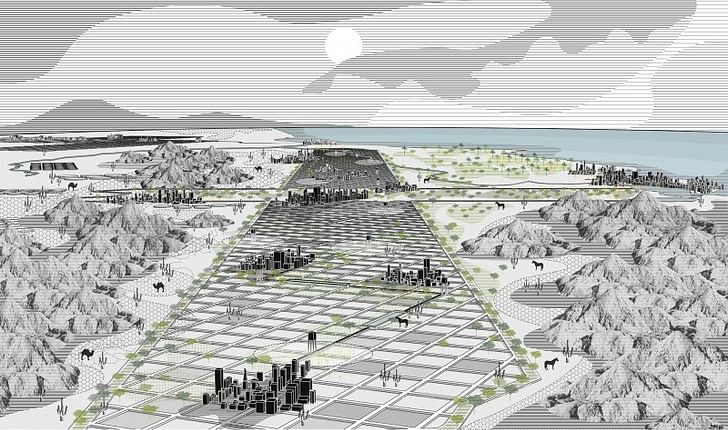

DESIGN EARTH, which is based in Ann Arbor, MI and Cambridge, MA, endeavors to engage with political ecology through the techniques of architectural representation. This often results in intricately detailed drawings accompanied by texts that draw from their research as well as a diverse set of references from literature, art, philosophy and elsewhere.

“We develop drawings that capture the entire world with a range of scales and visualize hidden connections by combining information from different spheres of knowledge with a pleasurable sensual experience,” they state. “A great fellow geographer Alexander von Humboldt referred to his drawings as ‘a microcosm on a sheet of paper’ and this is how we like to think of our drawings.”We develop drawings that capture the entire world with a range of scales

DESIGN EARTH recently published Geographies of Trash (Actar, 2015), which utilizes design tools alongside original research to map waste management and propose alternative ways of understanding, and living with, our garbage. For their installation in the 2016 Oslo Triennale, they created a series of aquariums/architectural models—replete with real fish—that represent human impacts and interventions in the Pacific Ocean.

I reached out to DESIGN EARTH to discuss the reaches of their practice, which engages with planetary-scale phenomena through a particularly architectural lens.

You study a wide range of geographies and ecological phenomena, from oil extraction to trash systems to orbital debris. Is there a unifying element to the objects of your research? And what does your research process look like?

Our design research engages technological systems such as those of energy and trash precisely because they do not respect the morphological boundaries between the country and the city. So, we can say that we are interested in territorial technological systems that engage urbanization’s contract with nature. The question is then: what is the agency of design in shaping such spaces of technological systems, particularly now that the ecological crisis has opened the black box of urban externalities all while these systems often remain essentialized by the alarmist rhetoric of “energy needs”, “waste crisis”, “green infrastructure”, or “food security”? DESIGN EARTH seeks to counter the spatial abstraction of such systems by precisely making geography the primary entry point to such issues. How can we think of things often referred to as “externalities”—or beyond the purview of urbanism? And how can we think of such environmental concerns beyond technophilia and technophobia? Can we reclaim the logics and aesthetics of such systems in the production of urbanism? And can such re-presentations bring them, to echo Latour again, into the domain of public and disciplinary controversies? How can we think of things often referred to as “externalities”—or beyond the purview of urbanism?

The structure of our book Geographies of Trash speaks to the fourfold approach: Construct, Represent, Project, and Assemble. First, we historicize and conceptualize the issues related to the issue at stake—identifying significant actors, legislations, worldviews, that are part of the question as we encounter it today. Then we produce a series of mappings and diagrams that represent these relationships in space across scales—from the block, township, territory, state, and world. The architectural project in this worldview is political in as far as it calls into question nothing less than the territorial organization of our world. In themselves, these representations are rhetorical criticism of social reality—of which spaces and which constituencies matter. Our work does not stop however at making things visible. A series of projects, often responding to issues brought forth in the mappings, speculate on alternative strategies, rituals and imaginaries for such systems. And fourth, an object in space assembles all the work and the people around the issue. This is roughly a very structuralist outline of the approach—the process in any of the projects would need to account for discoveries along the way, a fantastic newspaper image, life event (“Neck of the Moon” has a good story in that respect—let’s just say the umbilical cord), and many intertextual references that make of our work an ever unfolding exquisite corpse.

In projects like “Georama of Trash” and “After Oil”, you explicate that part of the motivation behind the projects is to make the public aware of the geographies and phenomena you are analyzing. Why are architecture and design useful media for conveying these complex systems?

If we agree that these complex systems matter, then we ought to think of them in their materiality. This project is fundamentally political because it brings spaces that were previously erased as insignificant into focus as matters of concern. Architecture shifts the debate from what Latour call “matters of facts” to “matters of concern”. If matters of fact insist that these systems must remain out of sight, matters of concerns require an outline of these systems that includes the whole scenography surrounding them. The term scenography is very important. On one hand, it highlights the importance of a specific site for these concerns. Our projects do not respond to trash and energy in the absolute, rather they propose situated questions: for example of trash in the Great Lakes and oil in the Gulf, and identify within these larger regions’ specific sites of relevance. So first, architecture is the specific context. Second, architecture is the diagram. It is the practice that spatializes these systems as artifacts in their thingness. It draws their precise configurations and engages their dimensions and forms. Architecture is also relational: it draws together things such as volumes of space debris, orbits of planets, gases, sunlight, and geological strata in ways that does not respect disciplinary boundaries between the sciences of the Earth.speculative design is inherently a method

Third, architecture is the medium, it is the necessary act of representation—“the machinery of the theater”. Our work has been investigating formats of engaging the public—be it the cautionary tale in a sequence of speculative drawings, visual constructs such as the panorama, or artifacts that mediate our relationship to the natural world such as the aquarium. For example “Georama of Trash” is a large drawing that immerses the spectator in the speculative world of Geographies of Trash. It puts trash at the center of the Theater of the World. Also, our project “Pacific Aquarium” deploys the domestic object of the aquarium as an aesthetic Trojan horse: its forms—and the fish!—draws you in to tell and hear some of the unpleasant grand issues of the Earth. For speculative design is inherently a method. It does not leave you to the dead ends of irrevocable ecological guilt. It is also a laboratory for trying out ideas about reality and the nature of the worlds we are assembling.

Could you speak to the use of historical and other non-architectural references in your work?

The drawings of DESIGN EARTH explore the possibilities of a geographic aesthetics that builds on surrealism as the procedure of using violence to explicate cultural relations. In that sense, our work draws on surrealism, not only as a set of references but also as method—of an exquisite corpse that weaves together a series of precedents. The projects could be a clin d’oeil or integrate past or contemporary aesthetic practices that think humanity’s relation with nature—be they Buckminster Fuller, Earth Art, or Malevich. Our project “Apart we Are Together” is a good example of how this intertextual approach materializes in a project. The source of imagination is always reality. You can see how the work also explores tones and modalities of narration—from John Hejduk to Russian cinema and feminist science fiction. Each project juxtaposes a text that is a sharp, hard political statement and a drawing that is open, evocative, and sensible. Donna Haraway reminds us, “It matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what concepts we think to think other concepts with.” We might add that it matters what representations we draw to outline the world with.The speculative imagination is a powerful material force—ask Marx!

Your projects often manifest as large, speculative infrastructural projects. Why do you employ speculative design when grappling with large-scale, material realities?

We don’t see the paradox insinuated between large-scale and speculative. Design thinking happens across scales—urban systems and infrastructures should not be left to an approach of “business as usual” or “problem solving”. Fantastic Materialism is the approach. There is a rich history to thinking speculative design at the scale of the Earth and even the cosmos! The speculative imagination is a powerful material force—ask Marx!

This feature is part of Archinect's October theme, XXL, which looks at the very very big of architecture and infrastructure. Next month, Archinect's theme is XS. Do you have a tiny-scale project that has a big impact? Submit to our open call by Tuesday, November 15.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.