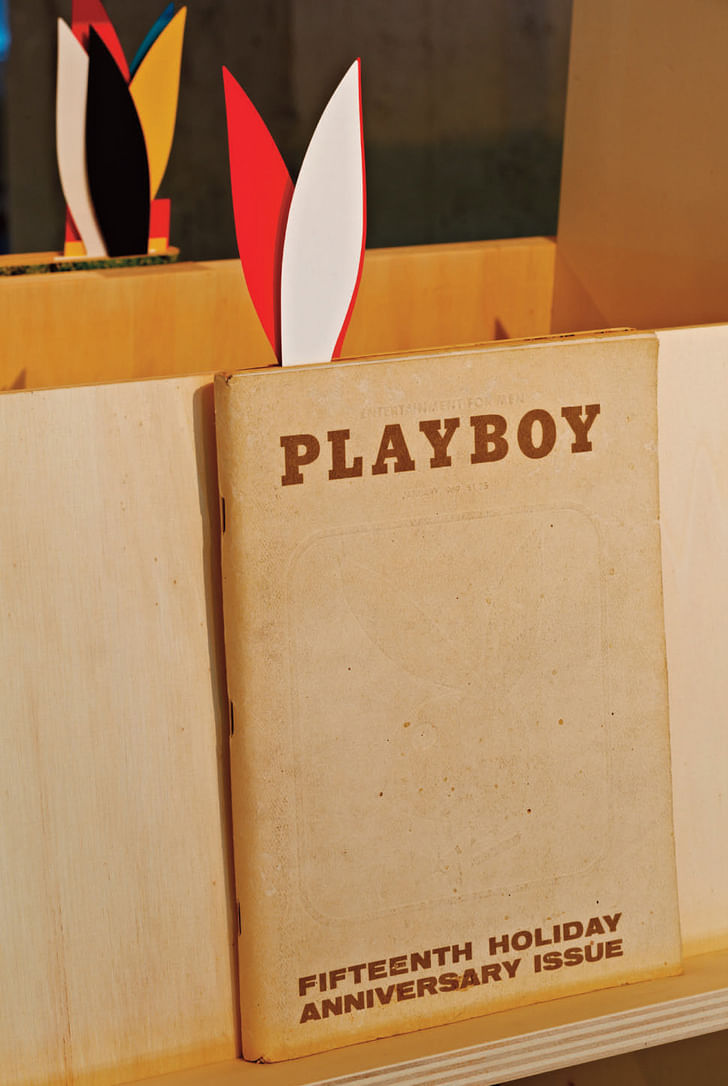

Playboy gets lip service as a leader in the sexual revolution, a vanguard publisher of emerging talent in fiction and interviews, and of course, a historic showcase for sexy ladies. While the publication has since lost its centerfolds, it is now being celebrated for its role in architecture and design – establishing both of those fields as firmly within the Playboy’s domain. Now on display at the Elmhurst Art Museum, “Playboy Architecture: 1953-1979” presents photos, films, architectural models and archival issues that illustrate how the ruling designs of the era fueled Playboy’s masculine fantasy, and the other way around.

Curated by Beatriz Colomina and Pep Aviles, the exhibition first was staged at Bureau Europa (Maastricht) in 2012, and is on display at EAM until August 28. Princeton University's School of Architecture and the Media and Modernity program collaborated on the exhibition's production, under a three-year research project led by Colomina.

I asked Colomina some questions to get a better understanding of the mutual influence between Playboy and architecture, and the inspiration behind the exhibition.Playboy glamorized modern architecture and made it palatable to a wide audience.

What initially drew you to researching the architectural aspects of the famed men’s lifestyle and entertainment magazine?

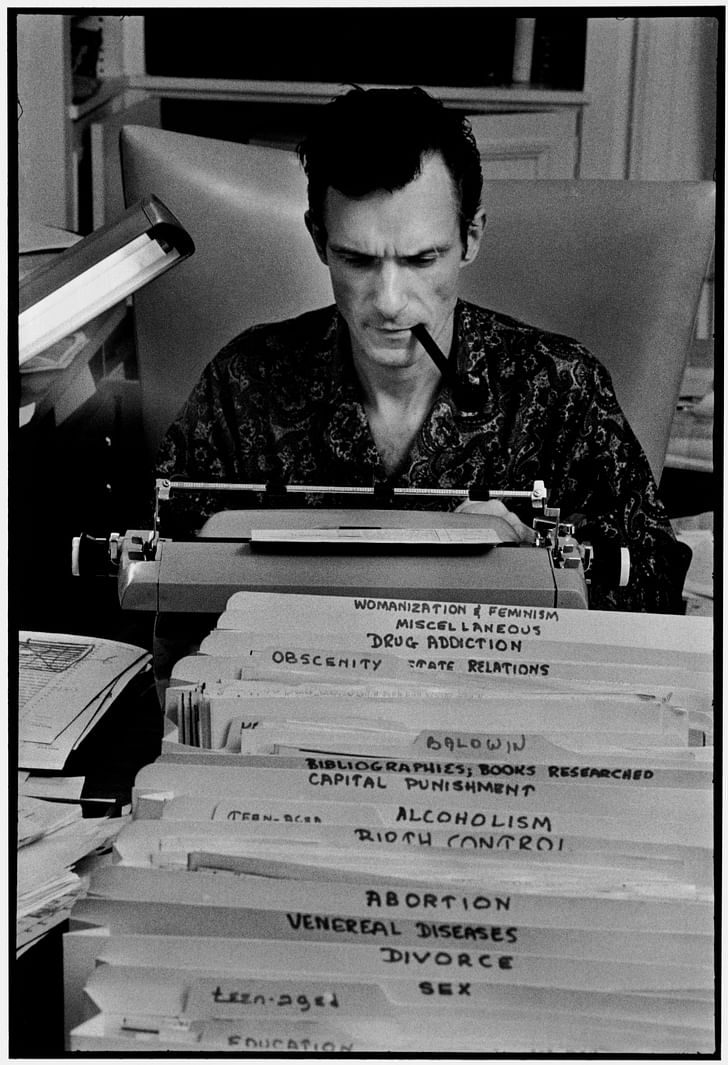

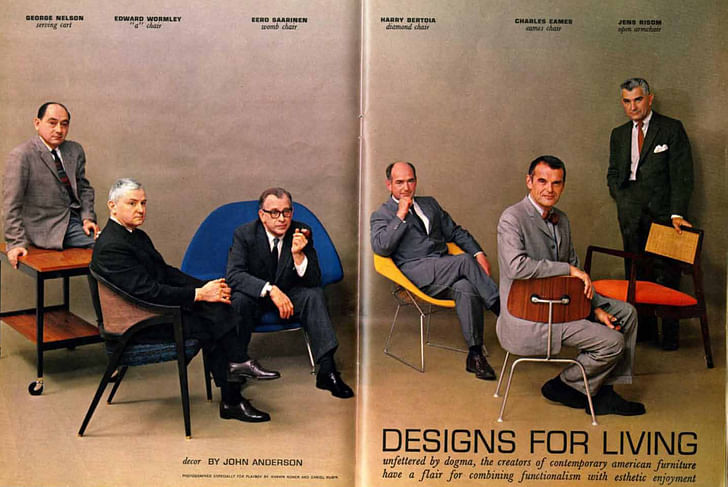

Over 10 years or so I kept noticing that modern architects and designers from the 50s, 60s and 70s were featured in Playboy. In the archives of the Eames years ago, for example, I found correspondence between Charles Eames and Playboy about a photo shoot for the magazine in which practically all the most remarkable mid-century designers participated (George Nelson, Eero Saarinen, Harry Bertoia, etc.). Then working on Antfarm, I realized they were in Playboy too. At first I thought it was a curiosity but then I started to wonder, who else is in Playboy? Because of course Playboy is famous for their great interviews with writers, philosophers, politicians, activists… but nobody seem to have realized that architecture was so important for Playboy. And that it had been the case since the beginning of the magazine in 1953. From the very first issues on, they published features on Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe. Playboy glamorized modern architecture and made it palatable to a wide audience.

Why focus on the period from 1953-1979 for the exhibition?

This is the interesting period in terms of architecture. They featured Buckminster Fuller and Paolo Soleri, Archizoom, Jo Colombo and other Italian designers that were part of the New Playboy never got interested in postmodernism.Domestic Landscape exhibition at MoMA of 1972. After doing a series of their own designs for idealized Playboy pads as seduction machines, they also presented many existing houses as Playboy pads. They published Charles Moore’s house in New Haven in 1969, when he was Dean at Yale and presented it as a Playboy pad, and likewise John Lautner’s Elrod House (1971), the Bubble House of Chrysalis (1972) and the House of the Century by Antfarm (1973). By the time you get to 1979 it is over. Playboy never got interested in postmodernism.

Playboy has featured interviews with such architects as Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies Van der Rohe and Buckminster Fuller, and designers Charles Eames, Eero Saarinen, and George Nelson. In terms of constructing images of masculinity, how did Playboy present these figures?

Architects and designers were treated as major cultural figures and published alongside other major literary figures, philosophers, activists and politicians such as Vladimir Nabokov, Jean Paul Sartre, Marshall McLuhan, Martin Luther King, Malcom X, Salvador Dali, etc. Perfectly dressed, they were symptomatically celebrated for their masculine sophistication, with subtle hints that they too are Playboys. In the very first year of the magazine, for example, Wright was already praised as an “uncommon man,” who “zooms” around in his Jaguar, has a controversial love life and “radical, exciting” buildings.

The exhibition posits that not only did architecture play “a crucial role in the Playboy fantasy world”, but that the fantasy world of Playboy in turn influenced architecture. How do you see this responsive influence being played out?

Playboy did not simply feature architects. They advised the reader on architecture and design. And they used architecture as prop for their sexual fantasies. Indeed, Playboy could not exist without architecture. With its massive readership—7 million copies were published at the peak in 1972—the magazine did more for promoting modern architecture and design than any architectural magazines or any institution, like the Museum of Modern Art.Playboy was perhaps the first life-style magazine with modern design at the center of everything.

How does today's architectural discourse reflect Playboy’s influence from the 1953-1970s era?

Playboy was perhaps the first life-style magazine with modern design at the center of everything. The magazine designed a new identity for men which included what to wear, what to listen to, what to drink, and what to read, but also what to live in: the furniture and the interior. Like a women’s magazine, it is absolutely filled with detailed advice and offers the reader a chance to rebuild themselves. Even the sexual imagination can be reshaped. The magazine offered the opportunity to use design to redesign yourself. If you look at architecture and design magazines today they are simply variations of Playboy. The only thing missing is the naked women, and it is important to realize that Playboy’s features on architecture, especially its extended series of Playboy Pads, were more popular with the readers than the Playmates, as if the spaces for seduction were actually more erotic than the woman supposedly being seduced.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

5 Comments

Clearly Architectural Record needs more naked women.

"Playboy never was interested in Postmodernism" maybe because it was unsexy trash.

That section reminds me of Andos Azuma house.

interesting. Even as a boy I often wondered why Playboy was so much classier than Penthouse or Hustler, I thought it must be all the text. Obviously at 12 and 13 you just flip to the women, but then in college I would actually read the articles, which was also a cool thing to tell girls who came into your dorm suite............"whats with the playboy magazine in the bathroom? Gross!" - random Freshman girl........"good article on cars in this issue." - roomate..............all makes sense now and when I think of slick modern male car commercials I will now connect that to Playboy. The "mental aura" was definetly there. good read.

Instead of this, read Paul B. Preciado, “The Male Electronic Boudoir: The Urban Bachelor Apartment” in Pornotopia: an essay on Playboy’s architecture and biopolitics (New York: Zone Books, 2014), 83-105. Preciado discusses how architecture can collaborate in the creation of toxic masculinity and its predatory behaviors against women.

Who knew Hef was such a modernist?

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.