Last fall, students in John Southern's “Architectural Media and Publishing” Cultural Studies seminar at SCI-Arc, democratically voted to interview Coy Howard, together, as part of the course. Their reasoning, according to Southern, is that while Howard has long been a fixture at SCI-Arc, he still runs a low-profile, foregoing final reviews in his studio and producing a fair amount of handmade work. The following is part two of a transcript of that interview, slightly edited for length and clarity.

Yun Zhang: Architecture nowadays is presented in a packaged, completed and standardized format that suits the needs of the norm. However your work carries a state of incompleteness and customization that is more of a couture idea, can you elaborate further if this is your intent?

Coy: The attributes and qualities that give a sense of individuality are the things which I strive for personally in a building, an object, a piece of furniture, whatever it is that I happen to be designing. I have had the privilege of designing many different things, from jewelry to furniture to films to graphics. In every case it is the attributes and qualities of uniqueness that I it is the attributes and qualities of uniqueness that I look to develop.look to develop. So, each of you are very, very different, right? Each of you is from different backgrounds, and you are interested in different things and you have different upbringings and you have different ambitions right? I’m interested in those things in terms of how they each contribute to who you are, and who you want to be, and how what you are striving to do in terms of becoming an architect, and how I might be of some help in that process in helping you become the productive, creative individual you want to be. I’m not interested in you becoming Coy Howard.

I’m not interested in you following exactly the methodology that I follow. I’m interested in you finding your own methodology, which makes sense to you; it feels right to you, because when you industrialize design education, which I think a lot of education now is, it’s all about technology and computers, you really prevent individual growth and you don’t do something which is really important in the world right now, which is the preservation of diversity.

the real task of every creative individual is the preservation of diversityWorld culture right now, has basically opted to become a monoculture, so Singapore is like San Francisco is like Omaha is like Paris, right? They are obviously visually different and they still have different cultures, but they are all moving in a certain direction, right? And they are all moving in that direction because of globalization. The whole idea of consumer capitalism…there are a whole lot of factors causing movement in that direction. For me the real task of every creative individual is the preservation of diversity so it should be our responsibility to essentially do things which are unique in the world and to have unique points of view rather than stereotypical views – right now the computer and other factors have really made architecture a tribal art. Many architects are practicing at a tribal level of common values. And I think that is really not the best way for the world to go, formally, socially, politically, and culturally.

Marissa Mortarana: Your studios seem to bring out the students personal aesthetic rather than impose an aesthetic. After a Coy Howard studio, what do you want your students to walk away with?

Well that’s an easy one, self-confidence, and authentic being – I think the root of my teaching is you can start any place if you have the right understanding of what it is you are trying to achieve, and it doesn’t matter what you start with. You don’t have to have a pre-conceived idea. You don’t have to have a philosophy. You don’t have to know what somebody wrote in France, although it maybe interesting. You are not going to adopt that philosophy into your building – you have to be sincere about what it is you are really trying to achieve. That to me is fairly clear, and I would hope if the students don’t have it when they come in to my studio, that they understand it, even if they don’t tend to embrace it.our goal is to essentially broaden and deepen human experience, and we do that primarily through creating aesthetic situations.

Architecture is essentially an aesthetic art, and in addition to the diversity that I spoke of earlier, our goal is to essentially broaden and deepen human experience, and we do that primarily through creating aesthetic situations. Those are the two things. The other thing is that I would like for the students to understand that any skill they pick up in one aspect of my teaching should be understood as a transferable skill, one that they can apply to something else and something else and something else. The developing of that ability, skills transference, is really important for students as they move forward. Because the things they are going to be doing in the future are different than the things they are doing in school. You have to be able to take those things, not only the skills sets, and the technical skill sets you have, but also the aspirational skill sets about what you want the work to be. So if you are all of a sudden asked to design some clothes, then you should be able to think about clothes in ways in which you demonstrate that you understand the possibility of doing some really beautiful things in terms of materiality, or detailing, or proportion, or shape. How you put those things together, down to the selection of the buttons, become really important things. It’s no different than what you are doing in terms of “is that going to be a concrete beam or steel beam? Is that a glass wall? Is it a curtain wall, or what’s the shape of that mullion?” All of those things are transferable, so it’s a sensibility foundation that I would hope I can somehow help build. A sensibility that is grounding in the understanding of the importance of relational structure.

The school has changed a lot, you talk a lot about digital technologies and all these methods and I think and even politically, how you were saying, everything is going towards one sort of movement of globalization, what have you seen in the change of your own teaching methods, that had to adjust or adapt over your time teaching here?

I don’t think it has really changed, honestly. I told you I was a bad student. I was really unhappy with my instructors. I was unhappy with them as people, I mean, they didn’t really seem to care about me. I was a seventeen-year-old-kid who didn’t know anything, and I wanted to be an architect, and I was just raw. And they didn’t seem to be interested in that for some particular reason. So I got really angry, but also I wasn’t interested in what they were although I was a bad student, for some reason I got a teaching job right after graduation.talking about primarily, and so while I was in school I began to really formulate ideas about teaching. I would go home after studio and make notes. I would make notes to myself about, some issue of importance to me and how the teacher refused to talk to me about it, and why he might have chosen to not talk to me about that. Doing so, I was figuring out ways he should have talked to me, so I became my own teacher and I wasn’t very good at it. I would think about issues that came up that should have been discussed that were really important to me, and then I would start researching that and going to the library trying to read and trying to find out. So I did a lot of thinking about teaching and although I was a bad student, for some reason I got a teaching job right after graduation. The job was in Oklahoma and because I was very energetic and eager, I think those are the right words, they gave me a lot of responsibility. So I worked really hard to try and figure out how to teach, and I developed pretty much the things I am interested in now. I think I am a lot more sophisticated about those things. I think I am a lot more sophisticated at teaching. I am a more effective teacher, but the interest has always been about the students, not about me and the value of these things I have talked about diversity and making sure you really understand and appreciate the potential of what you are doing in terms of how it affects people.

Andrew Cheu: What led you to UCLA after, I guess you were teaching for awhile…

Yes I was, I taught for three years in Oklahoma and then I wanted to go back to graduate school because I realize all of the things I wanted to know, I didn’t know, and I felt really inadequate as a teacher, and it really bothered me a lot. I felt there was a lot that I really wanted to be able to offer and I couldn’t do it because I just didn’t have enough information. The reviews are typically the faculty talking to each other rather than the faculty talking to the student, and so I don’t like that discourse.Education at the University of Texas in architecture was a fairly technically oriented program. It didn’t give me a broad, sociological, economic, or psychological foundation and so I applied to UCLA. They were starting a new school, a planning school. It wasn’t the architecture school. I decided if I went to an architecture school I would just play the games I knew again, and I didn’t want to play those games, so I decided I needed to put myself in a really rigorous situation that would challenge me intellectually. I got accepted into the planning program at UCLA. I was there for two years and during that two year period they were starting the architecture graduate program, they didn’t have any students, but they had the faculty and the faculty were discussing the development of the curriculum, and I became friends with some of the faculty that were starting to develop that program, and when I graduated with my planning degree, they asked me to join the architecture faculty. So I joined the architecture faculty and I taught there for a number of years, then I decided I needed to practice, and so I stopped, and then I came to SCI-Arc.

Marissa Mortarana: When one considers the weight architectural juries have within studio culture at our school, why do you choose to have gallery-style/in-house pin ups?

I think there are two issues, maybe three. The reviews are typically the faculty talking to each other rather than the faculty talking to the student, and so I don’t like that discourse. I’d prefer to talk to the student, rather than talk to someone who I could talk to in another situation, but that is just a personal choice of mine. The other reason has to do with the fact that architecture is a cloud problem and that the kinds of factors that need to be synthesized into a it is important that a student has the responsibility to put something together by hand.building to make it really successful are really very diverse and confusing, and not always very clear. It’s very difficult to actually put your finger on what makes something work and I find so many times in a jury situation, that the jurors go off into something that is very vague and it all creates confusion rather than clarity for the student. So I found that it’s, to my way of looking at it, and I know that other people have very different opinions, in many cases students leave more confused than they do otherwise, so I just prefer not to do it. And the other reason is that I think the students should have the responsibility to finish the work to a level of completion that when they put it on the wall, it attracts attention and demands respect and that’s more of a gallery situation. The work itself attracts attention, and the work basically engenders a lot of curiosity and interest and questions rather than being explanatory.

It’s not only that the work is put up in a gallery situation rather than a review, it’s that the nature of the review is radically different than the nature of the work that other students put up. Most students put up work to explain their project. My students don’t put up work to explain their project; they put it up to be the project. So it’s a very big difference. I think it is really important that students know how to make things and by making things I mean making things that have a particular impact, a presence. When someone views them or uses them the work should have emotional resonant that engages as opposed to explains. So much of the school has gone technological – 3-D printing, CNC, laser cutting, etc., there is very little work with the hands. I think that it is important that a student has the responsibility to put something together by hand. There is a Latin term, ‘verum factum’, that refers to the intelligence of the hand, an intelligence that comes from making things that you cannot get any other way. Putting things together with mindful observation teaches you certain things and those things become a kind of muscular memory, accrued through the handling, the experimenting with, and learning from the materials themselves, a muscular knowledge which is not necessarily nor easily conceptualized knowledge.

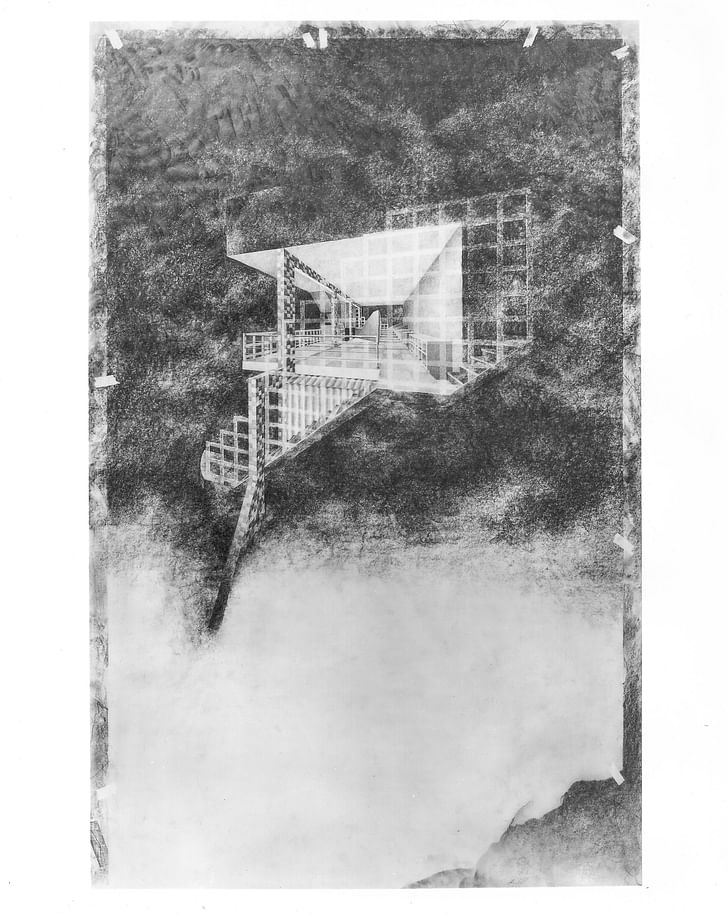

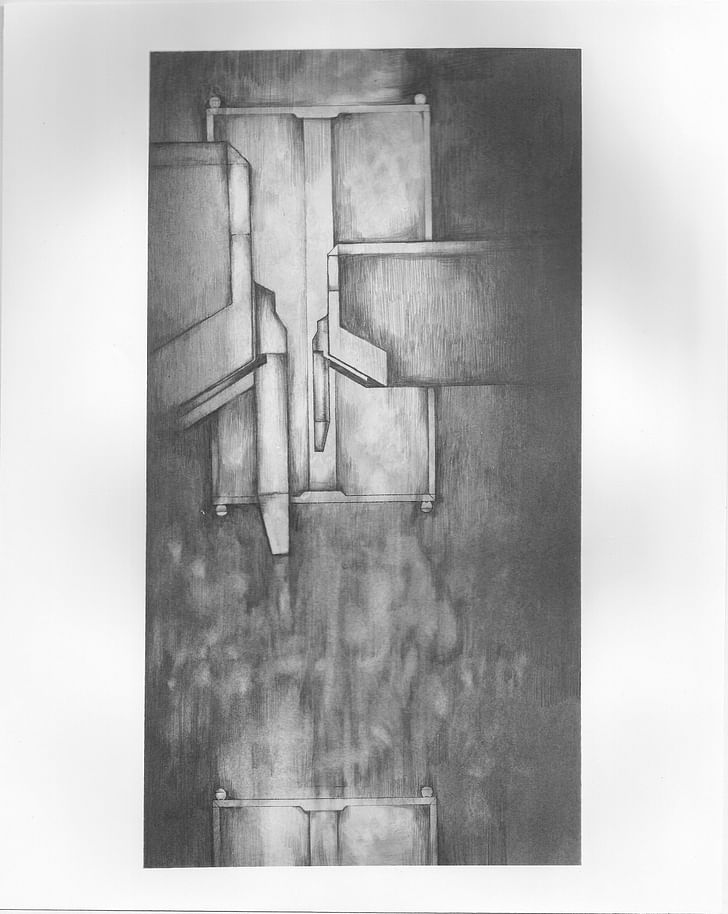

MM: Your “Drawls” combine model and drawing techniques that three-dimensionalize the drawing. They create depth through the use of illusion and materials such as the McCafferty Studio Drawl from 1979 which uses wood, cardboard, paper, and wire or the Daniel Drawl from 1980 which uses paper, graphite, Sumi ink, and bronzing. Can you speak about the origins of your Drawls and how they have evolved over time?

Well, they haven’t evolved, because I only did them in a brief period of time. They were there and then gone. I told you…I left UCLA, and I think those were done after…somewhere between ’77 and ’82 or ’83 was when I did most of those pieces. That period of time in architecture was the “drawing architecture” period. There were a lot of people that were doing a kind of muscular memory, accrued through the handling, the experimenting with, and learning from the materials themselvesdrawings and not building very much. On the East Coast it was the New York Five and they did all these beautiful ink drawings on mylar, and the Italians, Superstudio and Archizoom, were doing collages. So there was a lot of that kind of activity taking place and everybody getting published. On the West Coast of course there was also such interest. In my particular case it was spawned by the fact that there was a magazine, Progressive Architecture Magazine, which doesn’t exist anymore, and that magazine every year had a competition for work that hadn’t been built but was planning to be built. You had to submit a portfolio of that work and have it in by September 1st, midnight…It became a thing amongst myself, Thom Mayne, Eric [Owen Moss], and all of us – it became a way to get your name out in the world. That was the primary venue for making it in architecture as a young person in that period of time. Basically everybody was rushing to the airport at 11:55 to get their portfolios in to submit to Progressive Architecture Magazine.

I was doing these big drawings. At that time I think my first ones were all heavy graphite drawings. I don’t think I actually submitted any of the Drawls – I know I didn’t. In my studio everybody would be working during the week and I’d be trying to get these working drawings done. On Sundays I would just sit and look at things. I had some big drawings on the wall – these were ink drawings on mylar. I would just look at them, meditate on them. I kept looking and looking and thought I could do something with these things, so I went to the store next door, got some cardboard beer boxes, took them to my studio and flattened them out, and I just traced the drawing real quick, traced it onto the cardboard and started playing with the cardboard and that’s how they came about. It was really a Sunday afternoon, no pressure, relaxing, thinking about what I could do with the drawings to amuse myself on a Sunday. And they became more elaborate. The initial ones were these cardboard boxes, which I then painted with resin and bronzing powders and such things and then I made them much more carefully out of chipboard, and had them bronzed and then I framed them.

Basically it was a very short period of time, but it was really an important moment for me, because I wasn’t building anything, and so these things became surrogate buildings for me. In other words, that thing was the building, it was the architecture, so how could I make that thing have the kind of mood and presence I wanted the building to have. Previously, I had been doing these large graphite drawings – really quite large drawings of the buildings. Through doing the drawings and through doing the Drawls, I realized that the nature of what I wanted in the work – thinking about this "architecture as a cloud" thing again – the qualities these things became surrogate buildings for me.that I wanted in the work I couldn’t get at unless I did those drawings and build these Drawls because I didn’t understand it well enough. They were a mechanism for me to understand. I never did the big graphite drawings or the Drawls for clients. The clients have never seen those things. The people I did those buildings for, I never showed them. They were personally for me. I made them for myself to, essentially, develop a sensibility. They were something that I was using to figure out for myself what gave me the feeling of "this is working”. That’s what they were. Then I got busy and had jobs and was doing things, so I didn’t do them anymore. They never evolved. They evolved from the drawings to the cardboard, to the bronze framed one, but that was it. There were some small models that no one has ever seen. I made these little tiny small models of this whole series of houses I did and I made those into big constructions too, which I call, “Grafthings”. These models are like objects within larger compositions which are made out of scraps from my shop – I have a shop where I make a lot of furniture – so there’d be a piece of metal and I’d pick the piece of metal up (mimics placement into composition) – these are big things. No one has ever seen them. They’re in my house. They’re just for me. But I’m doing a book on the Drawls and the Grafthings. It’ll be out in maybe a year or so.

Now I want to come over and see everything! [laughter]

This is part two of a three-part transcription of Coy Howard's interview by SCI-Arc students. You can read part I here. Check back soon to read the remaining two parts.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.