Last fall, students in John Southern's “Architectural Media and Publishing” Cultural Studies seminar at SCI-Arc, democratically voted to interview Coy Howard, together, as part of the course. Their reasoning, according to Southern, is that while Howard has long been a fixture at SCI-Arc, he still runs a low-profile, foregoing final reviews in his studio and producing a fair amount of handmade work. The following is a transcript of that interview, slightly edited for length and clarity, presented in three parts.

Part I:

Coy Howard: Well I'll start it. To begin, I must say I found the questions that you submitted really a little stiff. I felt that they were too carefully worded. I didn't to get any sense of anybody's personality, or any sense of personal interests that each of you might have, so they seemed to have been de-emotionalized in some sense. They didn't seem like they were for me sitting down with a group of students talking. They just seem really rigorous. But I'll do my best if this is where and how you want to go.

Marissa Mortarana: Ok, so our first question is, “we are currently living in a time of computational dominance where architectural representation is concerned, but your work takes a unique approach towards design by using analogue methods. There are others such as Jimenez Lai, Smout Allen, Perry Kulper, whose work also emerges through analogue models. From your experience, how has working in the analogue contributed to the development of your work? And what qualities does it give you that digital does not?"

Well I'm older than thirty you know, everybody started working in an analogue model/methodology when you're somebody my age. It's basically just the way I work. I guess I never really thought about method at all in terms of working. That's not really the beginnings of things don't matter so much to me, but it's where they end up that's really, really important.anything that has interested me per se. I just never was interested in the technical aspects of methodology. I am more interested in what something becomes. So I guess in a sense, a broader answer is that the beginnings of things don't matter so much to me, but it's where they end up that's really, really important.

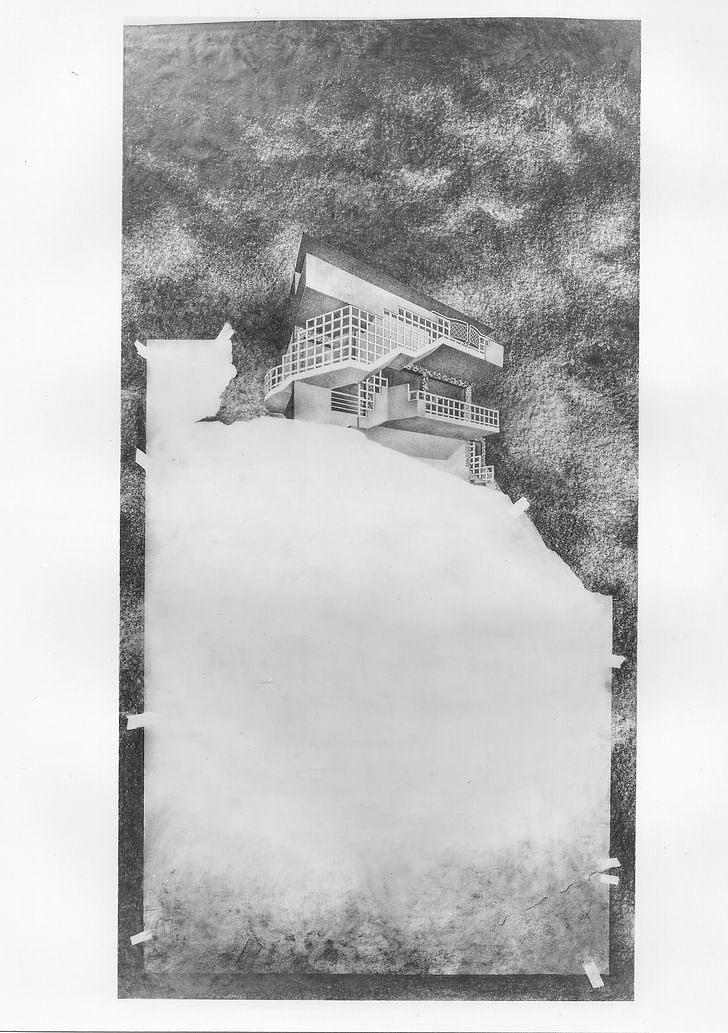

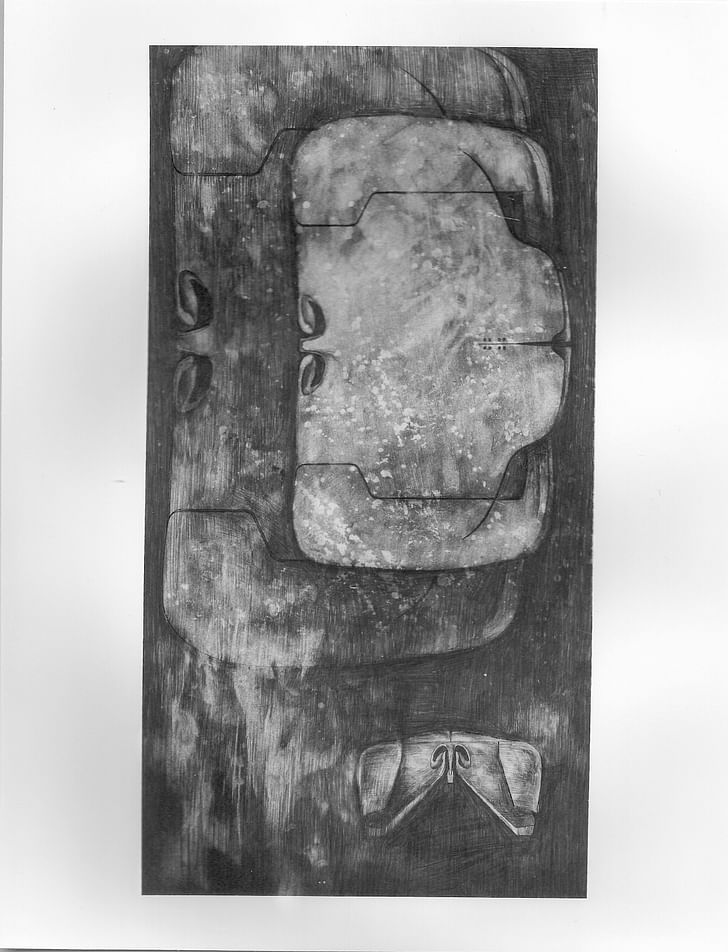

Certainly the computer is an incredibly powerful tool, and it's a wonderful tool and it does lots of things, and certainly allows a lot of people to do things that they wouldn't be able to do otherwise, but also it has a lot of drawbacks. So for me, I do almost everything by hand and by drawing, and almost all the work is in pencil, and with an eraser. And I tend to work on a part of a drawing or the design of a building over and over and over again so the paper that I use gets erased and smudged and torn and all of the things that happen in terms of the erasures and things like the scar tissue of a line that was there before I erase it is not quite gone, all those things can become very important in terms of the evolution of the design. Because I don't – when I work, I don't tend to work from any strongly conceptual basis, I tend to work, I would say from a more strongly emotional or philosophical basis. I'm much more interested in work that produces certain kinds of potentials which brings varied emotional situations and effects in to play. And so I’m always essentially trying to stay open to whatever is happening in front of me.

So if I make a mistake, I can say, “eh, that's better than what I was thinking I was going to do,” – so I try to use that in some way. And working by hand, at the level of drawing is faster in the initial stages of doing a building than it is on the computer. I mean I can sit down and sketch much faster than anybody I’ve ever seen at the computer sketch. It takes a long time to build a model – to build a three dimensional model and then work through the changes you want – so sketching by hand is an incredibly powerful tool. And by sketching, I'm not talking about any elaborate drawings or anything, I'm talking about things that are fairly simple. You know, being able to sketch out a plan and have some sense of scale as being accurate, being able to sketch a section and the implications of that, and sketch little perspective views.

you can't even exist in this profession without having it on the computerI tend to work on an 8.5x11 sheet of paper, and initially in the design, to put everything on this sheet of paper. So I start off by just making rough notes to myself, they're just little key words that are things that I’m interested in, things that come to mind, or things that I have to remember as being important or that the client wanted or whatever, just a few notes. And then I sketch out the site, and the site probably is, you know about this big, and there will be a section through the site and some idea of the topography or any strong features or view conditions. It's all basically there. And then I'll start playing with a plan, and at the same time I might think, oh maybe the material is this – and I might make a note of that as a possibility of a material as it's coming to me. There will be a section and then there will often be crude little perspectives, I may turn the sheet over and I may make little details, like if I made it out of “x” it'd probably have to have a detail of a certain nature, or showing this might be an interesting way to do it, but it's all on a sheet of paper.

The value of this is twofold for me personally. Number one I tend to work very, very close to the page and so I'm sitting on my desk like this with my hands on the table. So this 8.5x11 is my field of vision, everything is right in front of me. I'm not looking at a screen in front of a busy background, so this is what I’m looking at and so it's all there. And the minute I start playing in the plan, I can look at my notes and see if I'm doing something that's important there. Or I can look over at the section and say if I’m going to change that section in plan, I'm going to need to change that section in detail. So then that might change the way you move through the building sequentially or whatever.

You have to have the intent before you have the process. Now I don't think the intent is always a clear thing.And then at some point, I'm looking and well you know, it needs to be more regularized, so I might look back and look for geometric correspondences and things like that in the plan and section. But I get it all on the sheet and this is basically the concept drawing, and from there I take it into scaled drawings, laid out in more traditionally drafted versions. But that's the traditional way I work. Obviously I have people that work for me who know that, and put it on the computer, because you can't even exist in this profession without having it on the computer. So I have people that do that, and translate my sketches and drawings. And I'm constantly going back and forth with them, and they'll say, “well that's not going to work, what you did there," and then I'll do little sketches and just say, “just do this and that.”

What I find is that, and this is getting to your question, is that, what the analogue has gained me in working in two dimensions and three dimensions simultaneously, is that I've developed Unfortunately the computer has really amped up the belief that architecture is a clock problem, but it's not a clock problem.a really strong critical eye and I can figure out things pretty fast in my head without having to even draw them. So somebody can come back to me on the computer and say, “Coy this is not working,” and I say, “Yeah, but you modeled that wrong.” I don't use the computer, but I know how to make form, and I know how to make geometry, and so I can say that that's been modeled wrong, you have to model it this way, you have to go through this series of steps in order to be able to do it right. The virtue of that in my particular case is that I developed that skill by drawing. Now, other people can develop it differently, but that's the way I developed it.

Andrew Cheu: I have a follow up question. You made it sound very clear with the process you just went through with the 8.5x11, but I think a lot of us are interested in your creative working methods. At the beginning of the year you actually chose me as one of your volunteers and you always talk about the “high wire” and these two extreme points of working and your goal for students is to work in the middle as a critical point. Could you elaborate a bit more on that because I don't think that's a clear process at all, and I think a lot of us want to understand that.

Well, it's not a process, it's an intent. You have to have the intent before you have the process. Now I don't think the intent is always a clear thing. There are two mindsets that people traditionally have, now they have others, but there are two mindsets in regards to people thinking about science, social issues, and certainly architecture. They tend to see any given situation either as a clock problem or as a cloud problem. These two terms were coined by the philosopher C.S. Snow. He wrote a very famous book called “Two Cultures,” in which he talks about these two ways of working. Clock problems are basically problems that can be figured out, you know all the variables and you can figure those things out. Cloud problems basically don't exist that way. Cloud problems exist much more amorphously. You don't really understand all the factors, but you sense that they're there, but you don't exactly know what it is yet, and so you approach them very differently.you can't put your finger on something that produces an aesthetic richness, its just too complex.

In clock problems there are ways in which you set down what are called syntactical methodologies, you do this first, you do this second, you do this third. On the cloud problems you can't really do that. You have to really bump around a lot. By bumping around a lot you try this, you gain a little bit of understanding and then you try that, and you slowly circle what it is that you're trying to accomplish. Architecture is a cloud problem; it's not a clock problem. Unfortunately the computer has really amped up the belief that architecture is a clock problem, but it's not a clock problem. Anything that has to do with aesthetics is a cloud problem, you can't put your finger on something that produces an aesthetic richness, its just too complex. So you have to slowly gather all these factors and feelings into it. That's the background to your question.

When I talk about abstract expressionism and physiognomic expressionism in that particular reference and the importance of working in the middle, I am referring to the two poles of formal expression. Architecture is a cloud problem, where things are really diffused and you don't quite understand them but you want to somehow have work which is really rich so that it activates multiple modes of being, which activates intellectualization but also I don't think the students can or should be able to explain their work completely.activates emotional sensibility. You have to find a way to do both of those things. By operating in the middle of the two poles, difficult as it is, you have enormous expressive potential. When you solve a problem and it's a clock problem it's basically something that's going to be understandable. You'll never solve a cloud problem, but when you work on a cloud problem you'll bring it to some coherent resolution. That's an emotional resolution; it's not an intellectual resolution. You feel a coherency but you can't necessarily explain it, and that's one of the reasons I don't do reviews for my work. I don't think the students can or should be able to explain their work completely. I think that the work should be rich enough that it defies simple explanation. I'm not saying I'm anti-intellectual, you can talk about your work, but I think that at least one time in school you shouldn't be asked to do that.

It's the middle ground, the middle, muddy, cloudy ground that is really where the most interesting things lie. They don't lie in pre-defined, pre-conceptualized solution based methodologies. And the computer really biases things very much towards that because it's basically a syntactical set of operations. There are rules, you do this, then you do this, then you do this.

Well let's answer this one, “Please briefly explain your creative working methods. What influences its shape and continues to influence and develop in your work?” – Well let me tell you about my experience in architecture school. I was raised in Dallas and Houston, I was always affected by the things that had been abandonedTexas, and I went to the University of Texas in Austin for architecture school. It's about a two-hour drive between Houston and Austin. Houston is a big city, and Austin at that time was a small town. But on the way you had to go through a lot of small farming communities, surrounded mostly by rice fields and cattle ranches. I would go home a couple of times a semester, and driving through the countryside I was always affected by the things that had been abandoned, the farmhouses and the fence posts and barbed wire which were falling down, and weeds growing everywhere. Those things always had poignancy for me. They just really touched my soul.

Sometimes I would stop, and get out, and I would walk around in the fields and kick cans and find an old belt and those things had a history, they were really important to me. And I'd go in the houses and there might have been a piece of furniture there, a bible or something. There were always things there of interest to me. Then I'd go to class, and my teachers would always be talking about Mies van der Rohe and I would just snore, you know? I would just go to sleep. It just didn't interest me at all. It had no emotional impact on me whatsoever. And I just kept thinking, “there's something wrong here. This is really not right.” All they were talking about were things that are really easy to teach but they weren’t and are not now important in my life. I basically was a very poor student, and I was always telling the instructors in code that they were full of shit and so I was not very popular.

my teachers would always be talking about Mies van der Rohe and I would just snore, you know?As a result of that I just felt there was a better way of making and thinking about architecture than the way that I was being taught. So I set out to try to figure out what that was. That's the major influence that I can recall, those drives between Houston and Austin in which I saw those things. Every child has this point in their life where their physical world takes on a mythological presence, children become frightened of the dark, or they might have imaginary friends and they have to have their blankie or their little teddy bear. What we are doing at this stage of our development is embodying these objects with a spiritual presence that's important to us and gives us a sense of security and of control in trying to understand things that are really outside of our capability at that age to understand them. Everybody goes through this phase. I think I got stalled in that phase. I really liked that phase a lot. I always try to keep that in mind.

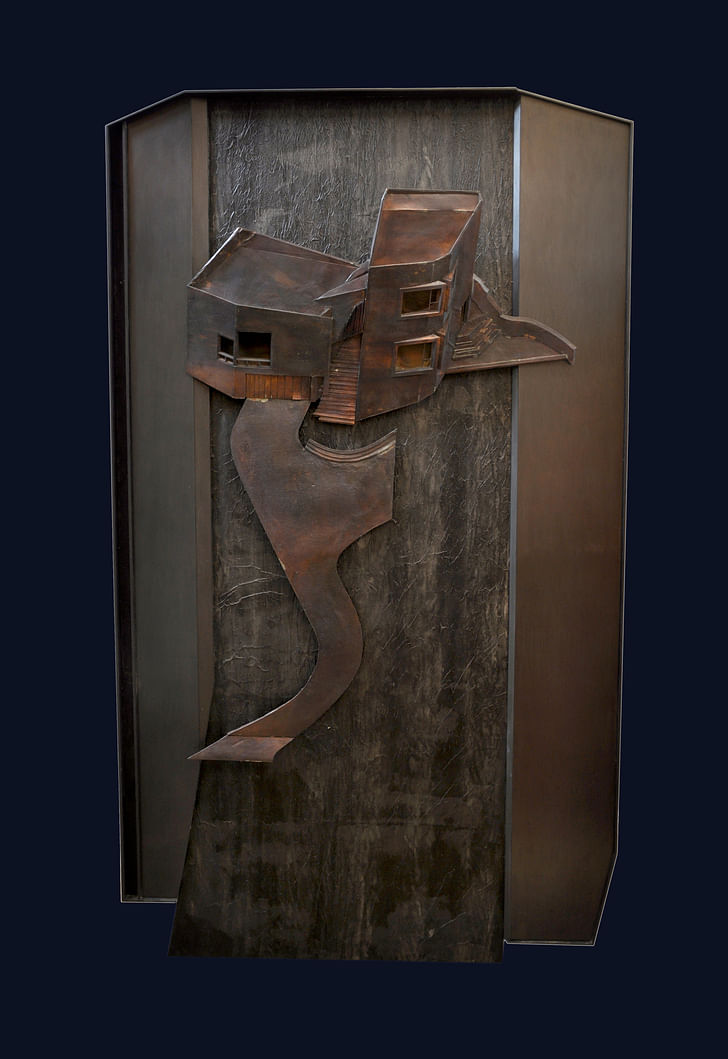

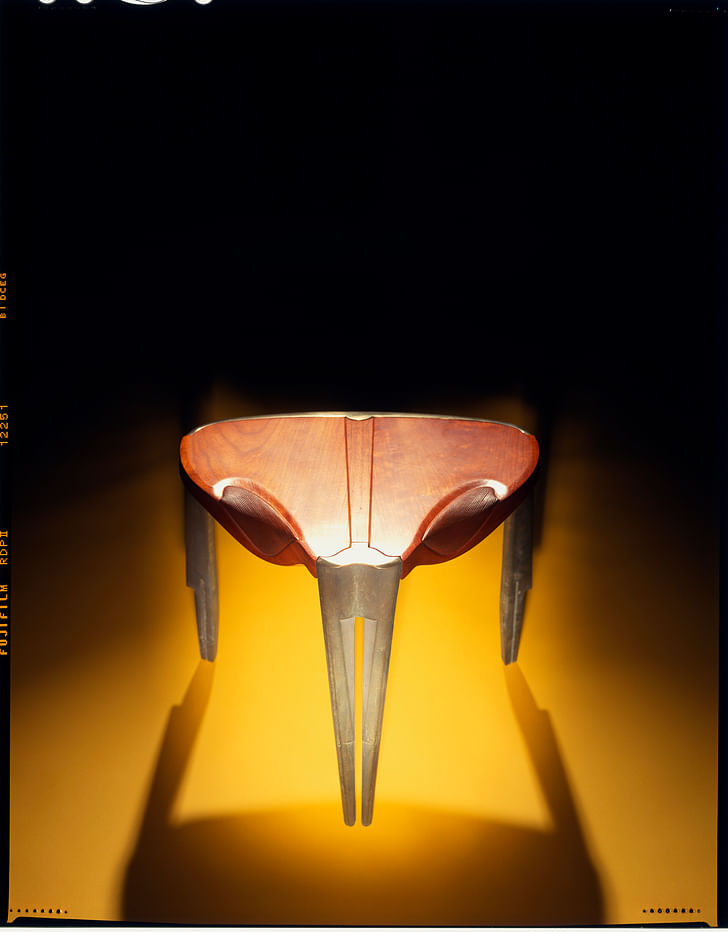

So when I go to a marble yard and I'm looking at marble I'm trying to figure out which piece of marble has a particular character to it that will really speak to me in some way – if I might use it in a situation which is going to be appropriate for that character. I'm always looking for that That fascinates me, that mysterious aspect of objects that are in the world that have this capacity to attract attention.emotional tone and that sort of feeling tone that all the various materials or particular shapes and forms carry. I go to thrift stores a lot, I go to swap meets a lot, but I don't go to buy things, I go to look at things because it's like going to a museum. You pick up something and you'll go, “Jesus, what is that? What does that do?” And it's on a table for tools, but you can't even imagine what it does. That fascinates me, that mysterious aspect of objects that are in the world that have this capacity to attract attention. I want to pick it up and touch it. Because it has a quality that it beckons to be touched, so I do, I touch it. Those are the kinds of things that really interest me and influence me a lot.

I go to museums. I'm very interested in the art world. I would say my practice, the things I do, is more influenced by art practices rather than by architectural practices. I tend to think about those materials and those qualities, and the ways things go together that have a poetic resonance rather than a technical sophistication or conceptual explanation.

AC: With all the material interests that you talk about, you go to thrift stores, is there anything that you are looking for specifically? You mentioned the drives from Houston to Austin and the cans and the things that touch your soul, so are there any materials or things that you always look for?

Well I don't think that I've worked with any material except the same standard materials that most people work with, I just try to use it in a special way. I would say that I probably have a stronger sense of tactility than some people that practice. I typically respond to things that have both visual and physical texture. All these things basically have to do with one issue. I'm interested in intimacy. I teach and I want to talk to the class, with you guys, because I really there's a fetish in America towards cleanliness, which I think saps a lot of energy and soul out of things.like this sort of relationship where you make some personal contact with somebody. I make it a point to learn everybody's name on the first day of class if possible, so it's really important to me that I establish a really strong relationship with the students. I like finding out how different the students are and what different skill sets they have. I've been doing this long enough now that I can figure out what's screwing them up, and I can figure out how to help them so that interests me a lot.

But to me, I get something from it. I get this sense of connection. So, it's the same thing with materials, like this doesn't attract me. [Pointing to a Formica table] Primarily it doesn't attract me because it doesn't have a strong projection of history and the history of its making. I mean, I know the history of these things like all of you do, and they do have a history but that history is not an interesting history, it's a technological, consumer-based history.

The things that really attract me are those things that have some suggestion of a different kind of richness to them. I tend not to use materials that are slick, and I don't tend to use any materials that look new and most materials are always obviously new, but I tend to age those products. If I'm using brass I will put a patina on the brass. The reason for that is that polished brass is not brass in its natural state. I want the natural quality of the material to be dominant. Now, I'm not trying to create a faux age, I'm just trying to let the material be the material that it is. The other thing is that there's a fetish in America towards cleanliness, which I think saps a lot of energy and soul out of things. It’s the environments that have a history of human use and presence that speak to us with profundity.

This is part one of a three-part transcription of Coy Howard's interview by SCI-Arc students. Check back soon to read the remaining two parts.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

1 Comment

Great Work and greatly inspiring teacher!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.