“How you design a building directly is ecological awareness,” states Timothy Morton, Professor and Rita Shea Guffey Chair in English at Rice University. “And your design is a game that will inculcate all kinds of ecological awareness. So realize that and act accordingly...”

A person of many parts, Morton maintains a menagerie of interests, populated by the likes of Percy Shelley and the atom bomb, Bjork and the Spice Trade, Martin Heidegger and climate change – among myriad other diverse “objects”. His ecocriticism is as accessible as it is challenging; it wields an increasing influence on a range of disciplines, from philosophy to ecology, art, and architecture.

Morton participates in object-oriented ontology (OOO), a popular movement in contemporary philosophy characterized by a rejection of anthropocentrism (the privileging of the human over the nonhuman), and "correlationism", the post-Kantian assumption that reality is a product of human thinking.Every house is a haunted house

His notion of “hyperobjects” – objects of such massive scale and temporality that they exceed the perceptive capacities of humans – enables a profound and radical way to think about, and learn to live with, global warming and the ecological “mesh”, more broadly.

Morton has written before on architecture, and will be giving a talk on March 14 at SCI-Arc, which has been prefaced by the unequivocal statement: “Every house is a haunted house.” I talked with Morton about some of the ghosts that haunt this strange object called architecture – from exterminated pests to dead philosophers – as well as a few of the primary concepts of his work and their relevance to architectural discourse.

You’re a strong voice in object-oriented ontology, a strand of philosophy that began with the work of Graham Harman (who has just joined the SCI-Arc faculty). For those still unaware, how would you describe OOO, and how does it depart from traditional metaphysics? How could an OOO perspective change the way we relate to “architecture” – a word that is itself something of a messy object, representing at once a discourse, profession, discipline, industry, and field of individual objects?

“Well, I’m very glad you asked me that question,” as they say. You know, I actually really like to think about OOO in architectural terms. You know Doctor Who, the British TV series? You know Doctor Who, this time traveling, free wheeling deus ex machina, and his machina is called the TARDIS, which stands for Time And Relative Dimensions in Space. The TARDIS is famous for being “bigger on the inside”. His companions, when they first encounter it, run around the TARDIS trying to figure out why it’s so different on the inside than the way it appears on the outside. And in fact, they go on to discover that it’s infinite on the inside. On the outside, it’s a police call box from the 1950s. On the inside, it’s rooms and corridors and doors and closets and power generators and...

What we thought was special about humans is actually incredibly cheapWell, at the beginning of modernity (late 18th century), European philosophy was beginning to show that human beings are TARDISes. They contain infinities that make them qualitatively (not quantitatively) bigger than the entire universe. All OOO does is argue that this isn’t a specially human trait. Everything is like that. To exist is to be a TARDIS – and that includes sentences, poems, ideas, hallucinations, dreams… That’s our motto, in a way. “If it exists, it’s a TARDIS.”

That doesn’t mean that everything is like a human or a subject or whatever. That means that what we thought was special about humans is actually incredibly cheap, this wondrous TARDIS quality is everywhere, at a bargain price that doesn’t mean you need to prove you have a really good credit card called selfhood or self concept or consciousness or thought or (human) destiny or (human) economic relations or (human) will to be admitted into the TARDIS club.

Actually our motto, in Latin, should be omnia occultantur: everything is hiding, or as Graham Harman likes to say, withdrawn. It doesn’t mean “shrunken back in measurable space”. Everything is encrypted. There are endless pockets and corners and rooms you never knew about in the TARDIS, so that you can never get tired of exploring it, because nothing you do (looking, stroking, ignoring, biting, running your fingers around, painting, doing an interview about, dancing on) will exhaust it. Who knows what the meaning of this poem really is? Who is this person I just woke up next to? I’ve known her for decades, and precisely because of that, I have no clue who she is. “This is not my beautiful wife!” We’ve all had that kind of experience right?

Things aren’t just lumps of extensional stuff decorated with accidentsSo this is all to do with a radical gap between what things are and how they appear. And for me, it’s deliciously paradoxical, because while things are never as they seem, they are exactly what they are. Raindrops give you raindrop data, not gumdrop data (what a shame). Nevertheless, raindrop data is just data, not actual raindrops. See what I mean? If this doesn’t amaze or slightly scare you, you might want to think about it some more.

One conclusion is that things aren’t just lumps of extensional stuff decorated with accidents. How things appear is deeply intertwined with what they are. We’ve been doing real ecological violence to lifeforms on Earth on the basis of this default lump ontology, which I believe was hardwired into a certain kind of agricultural social space long before formal philosophy put it into sentences.

One of the major concerns of your work involves a critique of “Nature” as a historical construction that establishes an illusory division between humans and nonhuman beings, ie. plants, animals, but also dust and air conditioning units, microbacteria and radiation etc. But for many of us, nature seems like a given. How is nature unnatural, so to speak? And why do you put so much emphasis (and urgency) on moving away from the concept?

Well, nature only seems like a given because we use it as a synonym for “everything”. But really, nature is a normative concept: it tells you how to discriminate between (say) good and bad. Natural ingredients versus unnatural (there’s a reason why they use that fake language on products). If everything is nature, then nothing can be nature – it’s a useless concept. And if nature is normative, then not everything can be nature. Some things have to be unnatural.

If everything is nature, then nothing can be natureBut this unnaturalness is just something we humans think for whatever reason about whatever it is. Being gay is unnatural, according to default homophobia. That’s something we are thinking and believing and hardwiring into social space.

What we call nature in the largest sense, like mountains and rivers or whatever, is exactly like that!

Now the trouble is, this kind of nature has also been hardwired into social space! It’s not just a concept in our heads. We think of this kind of nature as a nice harmonious, periodic cycling. There’s a physical reason for that. We started our settled mode of existence (the Neolithic) at the start of the Holocene, which was characterized by nice periodic cycling Earth systems (you know, the carbon cycle and so on). The funny thing is, we might have even caused that cycling ourselves through farming and hunting and so on! But even if we didn’t, so-called civilization was (dangerously) coincident with a nice harmonious cycling biosphere that was able therefore to run in the background like a smoothly functioning OS and thus massively contributed to this idea of humans-and-their-cattle-over-here, nature-over-there.

Nature is the Anthropocene in its less obvious, seemingly smooth (for humans) modeLulled by that myth of smooth functioning, we kept on and on running the logistical program that started in the Fertile Crescent and elsewhere, until it required fossil fuels to keep going. And we know what happens next…

So the really extreme way of putting it is, nature is the Anthropocene in its less obvious, seemingly smooth (for humans) mode.

Now can you see why I don’t like this concept?

There’s a default lump ontology going on here. Nature is what I find when I peel the appearances away. Underneath me, or in my DNA, or underneath the street, or over there in the mountains outside human built space, is something untouched, something given as you say. This ontology is directly responsible for the ecological catastrophe in which we now find ourselves.

The house acts as one of the major sites for both the ideological articulation of “Nature” – through opposition as well as enframement – and the physical practice of it. We desire our homes to be antiseptic, isolated, and exclusively human zones. So we filter our air, spray chemicals, set out rat poison – often inadvertently poisoning ourselves in the process, like some autoimmune disorder that we’ve decided to call dwelling. In fact, this dynamic is very much at play in haunted houses of horror fiction, where pests and ghosts rebel against the imposition of domesticity. Can you speak to this?

Wow, I love that phrase, “like some autoimmune disorder that we’ve decided to call dwelling”. I love it! That’s precisely it. In order to maintain smooth functioning (for humans), and to maintain the smooth functioning of this very myth of smooth functioning, a whole of violence is required behind the scenes on every level, social, psychic and philosophical. In every respect we’ve been trying to sever ourselves from other lifeforms—remember, you have them inside you and you couldn’t exist if you didn’t, and there’s more of them inside you than there is of you, so this is a major deal, this violence. But this is impossible. For instance, you mention how architecture has since about 1900 been based on vectors of pollution flow—gotta keep the bad air out, for instance, so you need air conditioning. But when you think about things at Earth magnitude, at that scale, where does it go? It doesn’t go “away,” it just goes somewhere else in the system. Nature, if you like, is a sort of fourth wall concept (you know theater?) by which we try to separate the human from everything else, and it functions in house design at every level. So yes horror fiction — I think also that the ennui poems of Baudelaire are fantastic on this. Feeling like you are covered in all kinds of spooky stuff as you sit in your flat...that’s real ecological awareness, that is.

Humans also exhibit symptoms of this autoimmune response on a more macro level. From the “Four Pest Campaign” of Maoist-era China to contemporary conversations about eradicating mosquitoes, modern history has many examples of attempts at “pest extermination” at a grand scale, which often had devastating effects. Chief among those, I think, would be the current and ongoing Sixth Mass Extinction event that you’ve written about quite extensively. Can you talk about this, and what it implies for the way humans understand what it means to dwell on the planetary scale?

The struggle against racism is exactly the struggle against speciesism, which is one of the ways this stage set maintenance works. Totalitarian and fascist societies can be weirdly ecological, in ways that disturb us about ecology: like eugenics, or animal rights (the Nazis were all over that), reforestation, Lenin talking about putting loads of fertilizer in the soil… Those social systems get the disgust level of ecological awareness, the Baudelaire level. But they get stuck there, and they try to peel the disgust off of themselves. That’s a way to describe the Holocaust, no? But truly, you can’t peel everything off, because its being-stuck-to-you is a possibility condition for you existing. So someone like Baudelaire with his moody ennui is showing you how to tunnel down into deeper ecological awareness underneath fascism. I’m sorry but we have to go down underneath it to discover less violent ecological modes.

The struggle to have solidarity with lifeforms is the struggle to include specters and spectralityWe make beings extermination-ready by designating them as uncanny, disturbingly not-unlike-us-enough beings inhabiting the uncanny valley [...] R2D2 and Hitler’s dog Blondi are “over there” on the peak opposite us, the good fascist “healthy human beings”. We try to forget the abject valley that enables this nice me-versus-nature, human-versus-nonhuman, subject-versus-object setup to work. But as you think about biology and so on, you realize that these peaks are illusions, and there is no uncanny valley, because everything is uncanny, because we can’t say for sure whether it’s alive or not alive, sentient or not sentient, conscious or not conscious, and so on. Everything becomes spectral, undead, in all kinds of unique and different ways.

So the struggle to have solidarity with lifeforms is the struggle to include specters and spectrality, strangely enough. Without this, ecological philosophy falls into a gravity well where it becomes part of the autoimmunity machination you just described. I so don’t want to live in that kind of ecological society...

There’s another sense of architecture as “haunted”, in terms of something like what Jacques Derrida calls the “architecture of architecture”, a historical concatenation of thinkers and buildings and social norms that together constitute an a priori set of rules and configurations for what we think when we think about architecture, even if those thoughts are oppositional. And then, on an additional level, we come into a world already built and absolutely saturated with the physical and immaterial traces of those who came before us.

Totally. This hermeneutical spider web around architecture, this architecture of architecture, isn’t a special human-scale feature of how things are. For OOO everything is like that. Everything is haunted by its very own spider web, in fact, without any spiders, and especially not human thought, needing to be involved. To be a thing is to be haunted. The only question is, to what extent are you going to allow yourself in your process to be haunted by this spider-webby quality of how things appear?

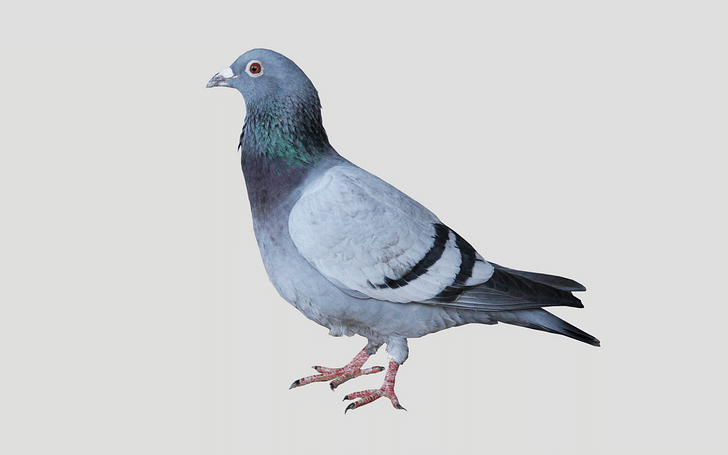

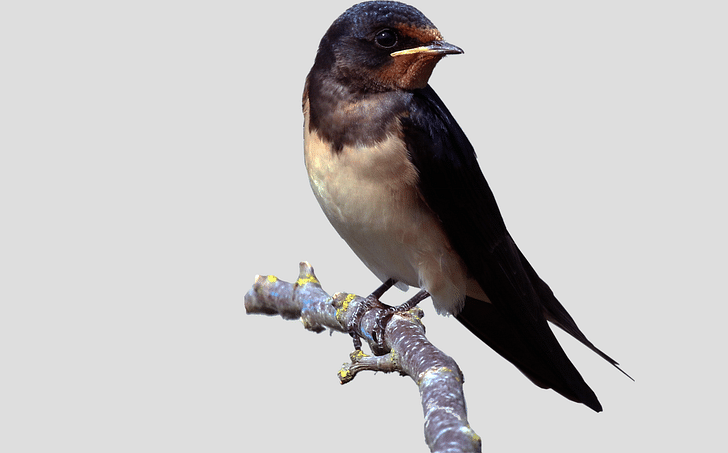

Buildings are haunted, not just by their past, but also by their future[...] Buildings are haunted, not just by their past, but also by their future. What does the Large Hadron Collider look like 10,000 years from now? Why don’t we include that kind of thought in design? Wouldn’t including that kind of thing – which implies a spectral, un-pin-downable future happening at all kinds of overlapping temporal scale – be exactly an ecological architectural practice? Houses are already not just for humans, right? What happens when the squirrel needs to get from A to B on your balcony?

For this reason, I don’t actually believe in the present! I think what we have—and it’s very obvious in a large, long-term structure such as a building—is a sliding of past over future without touching. The word for this sliding is nowness and it’s a kind of relative motion that the concept of present and presence (and the metaphysics of presence) is trying to delete. Lots of Western philosophy is horribly kinephobic, terrified of motion. It seems to want to get rid of it, to explain it away, to make it incidental to how things are. I am a huge motion freak.

You’re a noted scholar of Romanticism and Romantic literature. In architecture and landscape architecture, this is also a period that saw the emergence of picturesque gardens, greenhouses, and other forms of landscape architecture that seem to typify our idea of the “natural” as constructed, paradoxically, through artifice. Can you speak to this?

Well, that was before Romanticism per se. Romanticism per se is about smashing the picturesque, totally breaking through the false aesthetic frame that establishes a distance between me and nature, so that it appears nice and natural. When you get up close to a mountain with a magnifying glass, rather than trying to take the eighteenth-century equivalent of a snapshot with your Claude glass, that mountain starts to lose its human-scaled obviousness and naturalness, and it starts to exhibit all kinds of TARDIS qualities.Ecological architecture and art means: no more -isms!You see all kinds of crystals and inserts and stories in the rockface. So you start to wonder what’s real. This feeling of unreality and the scientific up-closeness actually go together. A Romantic poem has both of those ingredients.

We haven’t actually advanced any further than that, in art world terms, and one symptom is that we keep desperately asserting that we’ve found an even better -ism, an even better access mode. Romanticism is the first -ism, you know, and postmodernism, which thinks all kinds of inaccurate things about Romanticism [...] is just Romanticism 6.0 or whatever.

We’re just trying to rearrange the deckchairs of the -isms on the Titanic of anthropocentric functioning, in that sense. Ecological architecture and art means: no more -isms! Otherwise our mountain poem becomes a me-poem mediated through mountains. We need to get at the dark underside of this -ism stuff, which is coming up close to nonhuman entities without the condom of the human-scaled fourth wall aesthetic screen. By no means does this imply that we’ll be outside of aesthetics then. It actually means that we’ve noticed that aesthetic space isn’t totally human or human-scaled.

The dominant, mainstream attempts to incorporate ecology into architecture have been so-called “sustainability” and “green architecture”, both of which you’ve critiqued in the past. Sustainability, you’ve argued, relies on the assumption of a metaphysical “away” or bestand for all our waste and dust and messy human excess. But when you zoom out a bit, you see that the U-bend of our toilets leads to the ocean, our air conditioners produce “dirty air” as much as “filter it”, the contents of our trash bin end up in the front yard of our great great grandchildren. It’s a process of managing flows, rather than banishing matter – the “oikonomia” of the “oikos”, so to speak. Likewise, “green architecture,” besides often serving as a mechanism of greenwashing, presents an image of a cheery, tree-lined, and domesticated ecology. You’ve written a lot about “dark ecology” contra such “light green” ideologies. Can you explain your aversion to these terms, and what a “dark ecological” architecture might look like?

Totally. Things are intrinsically fragile. They collapse all by themselves, because they are different from how they appear. So you can’t ever have a nice perfect neat, tree-lined setup, as you put it. And you can’t have a nice tree-lined one-size-fits-all social structure, either, because social structures are also “objects.” You have to design with the inner fragility of things in mind. At some point, your wooden beams may be crawling with insects. Do you want to try to make something that will withstand everything, for ever? Do you understand the extreme violence that would take, precisely because it’s radically impossible? Wouldn’t it be better to make a place that was inviting for all the specters I was just talking about? And wouldn’t that look or feel a bit like a kind of “goth” sensibility, not that it has to have Scooby Doo crenelations or whatever.

Why can’t we have an ecology for the rest of us, the ones who don’t want to jump into a pair of shorts and hike up a mountain yodeling?I have a reaction against affirmative stuff. I’m like Adorno in that respect. Another reason for dark ecology is, why can’t we have an ecology for the rest of us, the ones who don’t want to jump into a pair of shorts and hike up a mountain yodeling? An ecology for the ones who want to pull the bedclothes over their heads and listen to weird moody drum and bass?

Dark ecology is definitely not despair ecology. That’s the way some have appropriated it, such as Paul Kingsnorth. That’s absolutely not true. It’s about how do you actually coexist nonviolently with as many beings as possible? What does that look like? To me, the guiding image is a charnel ground or, if you prefer a contemporary version, an emergency room. How do you restart hope, actually, knowing what you know about how things are? How do you start to smile once you know how entangled everything is, including all those hermeneutical spider webs? How do you smile for real, which means how do you get to cry for real? About all this truly horrible frightening stuff? Ecological facts are frightening, no? We are currently talking to ourselves about them in PTSD mode, which isn’t helping at all. Dark ecology helps you to move past that without deleting the pain.

One of your most influential ideas is that of the “hyperobject,” something that exceeds, in scale or temporality, human apprehension: global warming, styrofoam, radiation, etc. I’ve read this as suggesting a radical revision of interiority – we find we’re inside these massive objects (and that they’re inside us as well), which makes all our walls, our efforts to insulate the inside against the outside, seem very silly – or at least casts these practices, which are at the heart of architecture, into a different light. Can you speak to this?

Yeah. It’s not a contrast between specific and general, or empirical and universal, or whatever. What we’re dealing with now is reality at a bewildering, possibly infinite variety of different scales. There are simply things existing on different scales. Thing 1 is specifically X on Scale Alpha, but it’s specifically Y on Scale Beta.

What we’re dealing with now is reality at a bewildering, possibly infinite variety of different scalesThis also means, we’re not dealing a contrast between space and place. There is no such thing as space. It’s just that place is no longer a nice human-scaled cozy concept. Everything has place. The biosphere is a place—just not a for-us place that’s scaled to human destiny projects. The Solar System is a place. Things are not “in” space. Things are things-plus-places. That’s another way they are haunted.

We are not sinners in the hands of some universal invisible sadist with a beard who wants to kill you. We are humans existing in a number of specific, finite entities. These are also TARDISes! There are so many more parts of them—us, for example—than there are of them. Hyperobjects are physically massive yet ontologically tiny. So this story we keep telling ourselves, that wholes are bigger than the sum of their parts, is just a story. It’s part of a monotheistic religious setup, a setup that contributes directly to the Anthropocene because it’s an agricultural-age setup. Hyperobjects begin to show you that the whole is always less than the sum of its parts. This weird idea is actually childishly simple to think. If things exist they exist in the same way. A megacity is ontologically one. So are its streets, hibiscus flowers and power lines. There are always more of those things. So that’s why we can’t think megacities so well!

There is no such thing as space... Everything has placeHyperobjects mean: there are these truly big, bad, scary things, such as global warming and neoliberalism. There are these wholes. We can’t just reduce them to little bits or deny them. But being inside them doesn’t mean you are totally exhausted by them. Weather does so much more than just being what it is, which is a symptom of climate. It’s a bath for this little bird. It’s a pool for these tadpoles. It’s this warm damp patch on my sleeve. Hyperobjects are big but we have the controls, we can do something about them. They don’t just swallow all of human built space, they are inside me! I contain radiation and all that. So you can’t fight them off, as you point out. But that doesn’t mean we are screwed. That would be cynical reason based on never-proved explosive holism, which is a monotheism retweet.

Timothy Morton is Rita Shea Guffey Chair in English at Rice University. He gave the Wellek Lectures in Theory in 2014. He is the author of Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence (Columbia, forthcoming), Nothing: Three Inquiries in Buddhism and Critical Theory (Chicago, forthcoming), Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Minnesota, 2013), Realist Magic: Objects, Ontology, Causality (Open Humanities, 2013), The Ecological Thought (Harvard, 2010), Ecology without Nature (Harvard, 2007), seven other books and 120 essays on philosophy, ecology, literature, music, art, design and food. He blogs regularly at http://www.ecologywithoutnature.blogspot.com.

Morton will deliver a talk at SCI-Arc on March 14, 2016 entitled "Haunted Houses". In the fall of 2016, he will teach a masterclass at SCI-Arc as part of a new initiative in the undergraduate program under new the B.Arch Chair Tom Wiscombe.

This interview, which was edited for length, is part of Archinect's new series focusing on conversations between architecture and the broader humanities. Check back soon for more installations.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

3 Comments

Ugh whhhhhyyyyyyy isn't this a podcast?! I can't read it and draft at the same time!

Are there tickets to this event or can people just show up?

Speaking of our ecology, here's an excellent article by E. O. Wilson that holds nothing back if we are to steer this ship away from ecological disaster. His main point is we have to retreat from the natural world to allow it to heal for the sake of our progeny. What this means for architects? We'll have to design not just sustainably, but humanely.

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/13/opinion/sunday/the-global-solution-to-extinction.html

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.