Architect Ben Nicholson teaches architecture at Illinois Institute of Technology College of Architecture. Throughout his body of work, Nicholson has questioned and rearticulated the inherent meanings within architecture. He creates a critical inquiry that exposes the confluence of systems and desires at work within architecture and Western society. Some of his most notable projects include the Appliance House (MIT 1990) and Loaf House (1997, CD-Rom from renaissancesociety.com) . As part of his long-standing interest in American culture, he contributed to Hartmut Bitomsky's documentary film B-52 (2001) . His recent writing and design projects include The Hidden Geometric Pavement in Michelangelo's Laurentian Library , a book that muses over the nature of number, geometry and the structure of knowledge, and The World Who Wants It? , a satire on Western method. Perhaps this newest iteration The World Who Wants It? creates the most radical and earnest look into the symptoms Nicholson has been musing over for the last two decades. Archinect editor John Jourden spoke to Ben Nicholson at his Chicago studio to discuss Nicholson's outlook on the role of the architect and his book The World Who Wants It?

Left: The World Who Wants It?

Right: Thinking the Unthinkable House

(0:06) Congratulations on your new book The World Who Wants It? I really enjoyed reading it, and I have since recommended it to a fashion model, a family of four at Thanksgiving, the Chicago Architecture Club, and the Archinect Community at large.

Oh have you?

(0:28) I understand you were born in Newark, England, and then came to the United States for your studies. Can you talk about your experiences in the British and US educational systems and how these two trajectories formulated your perspective on architecture?

I certainly can. I've just written a document for the AA architectural education symposium. There were twenty people speaking about education with no slides, and no one could have any slides...[Appearing in a feature next month. ]

First, I was in Wolverhampton , known as the armpit of Newark - there were pork sandwiches everywhere, the Sex Pistols were playing there and it was raw - a very raw town. It was a place in a state of natural despair - an old Birmingham carpet-making town. I was originally going to be a charter surveyor - I didn't know what I wanted to do. Actually when I left school I went on trip around the world - I only got as far as Australia, but like a bloody fool I cut it short because of a girl. It's probably one of my big regrets in life. But anyway, I had terrible exam results, Cs and Ds, nothing - I couldn't get into university so I had to go to a technical school. I ended up looking at them all and they were completely miserable. Later, a friend said have you looked into the AA ? It sounded like a fairly interesting place, so I went down there to have look and instantly fell in love with it. I presented a portfolio of basically my travels to Indonesia and India. As an institution and for myself it was like love at first sight. They were terribly excited about it - they were just encouraging, like I mentioned I'd love to do this, and they said, "Well go down to the shop and do it this afternoon, they'll help you!" It was an incredible interview. The way the AA at that time took in prospective students for portfolio interviews, as I later found out, was with their top educators and was taken very seriously - unlike the current situation for students, who now have no idea how their work is being vetted. So I went to the AA for a year and realized I had to earn money, because it was expensive then. A friend of mine, she was an American and I was looking for one. You see, Americans were rich, at least in the English psyche; it was like if you touched an American you'd instantly turn into gold. So I was looking for an American to get me a job so I could earn money very quickly, and low and behold I meet the most wonderful people, Bob and Phyllis Goldman. He was a filmmaker, and she was nutty and wonderful. Jewish New Yorkers. They were the most cultured and interesting people - so they got me a job working as a waiter in a yacht club in upstate New York. I later came down to New York for a couple of weeks to stay with them, and they decided to see if they could help me out"

Just to give you some sense of situation - one week in New York after having been at the AA for one year, I was told by my teacher Sue Rogers (the ex-wife of Richard Rogers ): "Go see Richard Meier , a friend of ours, and see if he can help you." So I go to his office and I had no idea who he was - I was a first year architecture student. He says, "How can I help you?" I said, well, 'Sue Rogers sent me here, etc.,' and he says, "Okay, here is a key ring to all my houses in New York and Long Island that I've ever built," and he slides the key ring across the table. Then the Goldman's had a friend of theirs who owned the great tennis court house by (Charles) Gwathmey . I went to stay there at this house, and there were two other important houses I saw in the area. The first was the Gwathmey House, built for Gwathmey's parents Robert Gwathmey and Rosalie Hook, who are very important artists. I was in the compound there and met Mr. (Robert) Gwathmey. He invited me in and said there is quite an interesting house near by, here are the directions. So I go off on a bicycle he lent me - go up to the door of the Chareau House, the one (Pierre) Chareau house in America, and the door opens and a huge man with a tennis racket emerges and says "Who are you? Well, I'm Robert Motherwell , what do you want?" [Laughs] I had actually heard of Robert Motherwell at this early stage. And he says, "Oh I have a date - just do whatever it is you have to do, just don't move anything!"

Then, Tod Williams picked me up in his jeep and took me around, in the 70s, to all the things he was making - all the first houses. The gang - they were like sharks. (Charles) Gwathmey was building his house, and they would all bump into each other on a Saturday afternoon. By the weekend, the Goldmans said "I think we can arrange for you to go to Phillip Johnson's 25th anniversary for his Glass House ." So across the water I go, up to Connecticut, and it was everybody, (Alfred) Hitchcock - all the great monumental people. By this time I was beginning to know their names, everything was open, and it was an unbelievable experience for a first-year student. Within the same time the Goldmans said they know a very interesting man up at Columbia . I called him up and mentioned the Goldmans, and he said "Fine, why don't you come to Fallingwater , I'm taking my students." It was Edgar Kaufman, and he had this annual bus ride with Columbia students to Fallingwater. So we heard these stories for four hours going in one direction, got put up in a hotel, hung around the house, and he told all these incredible stories.

This whole time in New York was the defining moment in my education - I have to say. At that point though, I refused to ever have a white building! It seemed that all the houses that Richard Meier had given me the keys to... they were all empty, because the owners had divorced. I was about nineteen years old at the time, and I was thinking, "Something is not working here, and it probably has to do with these poor fuckers that have to live in here!" [Laughs] And that was the high-flying society of the 'Whites' - the great New York Five basically, and I basically had a fit - my experiences with British and American Modernism and the first moments of Post Modernism were severed completely at that point.

After that I began to study with a man by the name of Tony Gwilliams, who was a Bucky Fuller aficionado - he would take us to Bucky Fuller lectures that would go on for five hours, which is long, especially for a twenty year old. [Laughs] Tony was nuts, in a beautiful way. He was a contemplative, visionary man. He was working on his Mantainer project, which was a 1MX1MX2M house that you could take around with you and released you from bourgeois culture. I was a good country boy, and I had never met anyone like this, let alone a radical, closet Bucky Fullerite. In my eyes it was like, hello - the world is out there. Tony one day said "We're going to have a happening." The studio goes into a room and there is a tomato, made of plastic. Tony says "Come on in, come on in to the tomato," and in the tomato there is a television with soap operas playing, a record player spinning at 33-1/2 rpm, a tape recorder, an 8 track, a radio, and lord only knows what else. There is all this stuff going on, and the pièce de résistance was a video of Tony shagging Charlene, who was a student in this class.

(10:10) [I laugh] This was at Cooper or the AA?

Not Cooper. Nah. No way"Not there.

The project was about multidiscipline - talk about multidiscipline that was a lesson in multidiscipline" Anyway, that was sadly Tony's last moment in academia. He got excommunicated with Charlene, who he lived with for a very long time - I think they now have broken up, but they were very, very close to each other.

So that was a strong education, very strong. [Laughs] That was my second year! The third year, there was this little man from New York who began teaching at the AA, and I asked Sue Rogers, "Who could I study with this year?" She said, "Pick him, he's interesting; he comes to us with very good credentials." It was Libeskind . So the first semester, I was with another professor, and it was a bad match. In the second semester I got Libeskind as my studio critic, but by that time I couldn't work. Then suddenly something twitched: I can't remember what it was exactly. By then I had basically become disenchanted, and hated the whole world of architecture. Libeskind mentioned I should look at the drawings of Jean-Jacques LeQueu and all of the French Revolution-era architects. I got the book and realized this does look interesting! I started producing - producing work with an ecstatic addiction. I made this project that was sited at Trafalgar Square with these creatures and animals, which included a text about these buildings that were in the shape of creatures, such as the consumption bird, the palindromic urinator"

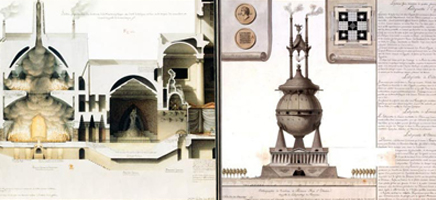

Left: Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Section perpendiculaire d'un souterrain de la maison gothique

Right: Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Elevation of the tomb of Porsenna, king of Etruria, known as the Tuscan Labyrinth, 1792

I wanted to go to Paris to investigate these LeQueu drawings closer. Once again a girlfriend - I told her I want to see these drawings, and she said, "Well go and see them," and I say, "I don't have any money." She was traveling there the next day by airplane and said, "Why don't you come with me and go on your bicycle." I said, "Okay I'll race you." This is at 9 o'clock at night after a bottle of wine and literarily I ran downstairs got on my bicycle and I just started cycling to Paris. And this bicycle was an old five-speed or something. It wasn't even a ten-speed - it was a trash bike. I was fit at that time - I mean domestic fit, I didn't exercise or anything. I got on to the five o'clock ferry from Dover to Calais, got to the other side and just started cycling. When I was overcome with exhaustion I'd pull over to the side sleep in a ditch, eat a bar of chocolate, and get on the bike. [Laughs] Anyway, I arrived at 3 o' clock in the morning the next day, like 32 hours riding or something, solid cycling. In the middle of the ride - in the middle of the evening, a beautiful evening, the pedal freezes up, and I had no tools or anything. [Laughs] So I limped into this farmyard and this farmer - just as in America, they can fix anything. He took the pedal off and replaced it with a pedal from his daughter's tricycle. [Laughs] And I say, 'Thanks buddy I'm out of here!'

I got to Paris and I was terribly excited because I had this date. I didn't really know this person very well so I was terribly excited, and I rode up to this huge house, like major mega house on the outskirts of Paris. It's difficult to find a house with no map at 3 o'clock in the morning in a foreign country and where you don't speak the language. [Laughs] I remember the house, it was just full of candles, and it was her boyfriend's house, so that was a great start, it was fine - it was just the beginning. [Laughs] I went in the next morning and cycled into Paris. I wandered in to the library (Bibliothéque nationale de France ), presented a letter, and they showed me these staggering, seriously good stuff (drawings). Buildings in the shape of strange smoke, cows, and all these sexual"(well, they didn't show me all the good stuff) LeQueu lived in a brothel after he lost his day job. It was a seminal collection of work, and he was a forefather to the surrealist movement, as I later found out, and was deeply influential to Marcel Duchamp .

Left: Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Section perpendiculaire du moulin des Verdiers (avec des changemens [sic]), dans la Vexin Normand, 1778

Right: Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Et nous aussi nous serons merès, 1792

This was the kind of education I received: "You want to do something, well go and do it, we'll help you in full." For instance, no one was teaching drawing at the School (AA) and they arranged for me to go to The Royal Academy , to study with one of the best life drawing professors in the world. That's how I learned my hand, from this guy who would allow me to sit there and draw. I would work on one area of a hand or palm that was about this big [motions with both arms] and it had to be 'on' and beautiful. I never was very good at it, but I learned a great deal. It was the AA! It was totally night and day: They'd look you into the eye and say, "you want to learn we'll help you. And if you don't, well then fuck you."

Libeskind had it in my mind that I was a monumental student. He took my Travulgar Square project back to New York, to the Cooper Union and got me a place there to study. I had no idea how simple it was to be unhappy as I could be there. Every day at 2 o'clock it was like a monsoon, I would leave the building and cry - walk around New York and cry. It was the densest tyranny of an unhappy experience. However, I loved being there through all of that and met some fabulous people - deep friends I still stay with to this day. I had brought all of this work with me from the AA, mountains of drawings, and they were like, "Well that's okay." It was a staggering moment, and I had to learn to see the world. And it wasn't going well there, and then Libeskind got the job at Cranbrook , so I went back to the AA to try and get a degree there, but my mind was in America. I had three extraordinary years at Cranbrook compared to my other experiences with education in America. The experience with education at Cranbrook was very much based on individual motivation. There were no courses. It was either you're going to work or you were not going to work. If you were not going to work you graduated early. You got the express degree which is a two-year degree. If you were into it you got to stay for three years. There are amazing people who came out of that program: Donald Bates , Raoul Bunschoten , Jesse Reiser , Karl Chu , and Hani Rashid .

Regarding architectural education, to repeat your question, I followed the teacher(s) wherever they were and I didn't care about the institution or where they were, it was more about the person. Sometimes people led me to them, and sometimes I went searching on my own, leaving a trail of bureaucratic destruction that I would not recommend anybody doing, because it was an agonizing process. That's how it worked; the issue was the love of learning and a hard game of pool.

(18:08) In your essay "Renouncing Autistic Words" (document courtsey of Ben Nicholson) you "audit" the American architectural pedagogy at IIT. Can you explain the difference in the architectural education you received through the AA, Cooper Union, and Cranbrook compared to the one formulated by Mies and his followers at IIT when you began teaching there?

I have taught there for over fifteen years now, and I have pretty much figured out. The trouble IIT has in integrating with the world is practically the same as the division between Sunni and Shi'a Islam . I figured it out - I read about Islam a lot, and I'm fascinated with it. The relationship basically goes like this: when Mohammed died the issue was who would get to be the big one, who gets the authority. The Shi'as felt this issue had to basically go through the bloodlines, and the Sunnis felt (in terms of succession) it should be the best man for the job. So the Caliph , which is a Sunni system, selected from the best people for the job, and they were intellectually minded, the best leaders - there is a whole list of words as to what qualifies the proper type of person. The Shi'as felt, no, it's got to be by blood, and that's IIT, that's the difference exactly. The Shi'a Miesian's believe that only if you were touched by Mies or you were touched by someone that was touched by Mies can you receive true Miesian Enlightenment. It's a spirit, right? There is no other way of learning. The Sunni Miesians, on the other hand, believe that the best interpreter of Mies is the true lineage. So in essence the true leader of Sunni Miesianism is Rem Koolhaas , right? He's the true leader, and then he delivered this incredible blow right into the midst. So this is the issue of bloodline, being touched is one kind of truth versus a method of study and interpretation. At IIT with our pluralistic leader, (Donna) Robertson makes both sides just share the same table, not that she has any say in the matter, but both creatures feed at the same trough"

(21:25) Sounds like a sort of family squabble?

It's not family you see! It's family and then the adopted ones, or perhaps more like self-claimed orphan adoptees. I now realize that there is no way the two could ever speak to each other; it's too impossible because of this bloodline. Of course they can speak to each other, because they have to, but the issue is they keep this division. So I'm a Sunni Miesian. [Laughs] Although I find the Shi'as (talking about Islam) more interesting...

(22:08) Because they're more spiritual?

Right. Shi'as get at the body in a better way. You know I'm not an expert, but I want to be, because it's a subject that is deeply relevant and of interest to me.

(22:48) Recalling a popular quote from John Hejduk, who states, "When an architect is thinking, he's thinking architecture and his work is always architecture, whatever form it appears in. No area is more architectural than any other." In Chicago (and perhaps in America in general) there seems to be an attitude that an architect's worth is measured solely through the act of constructing buildings. In the context of these opposing viewpoints can you discuss how you view the role of an architect?

Well, that's a good question, right on the money. My education, which of course is rooted through Hejduk, Libeskind, and Fuller"architecture for me is the best expression that we have to make comprehensible very complex systems. For the last five or six thousand years, architecture has been the best expression of human endeavor.

I have a book here of buildings from twenty-five thousand BC, that's quite a long time ago. These are huts built out of mammoth bones. These buildings were beautifully made, from the bones of the body into shelter . These early builders utilized their environment in a brilliant way. Here, check this out. [Shows pictures from book] "Huts made from jawbones of mammoths,""see how they are built? You put the jawbones together to form an arch at the top and clad them with different types of materials. I have been studying buildings from this era very carefully. See here? This is mammoth ivory, and I'm interested in these things that I believe are very early signifiers of production and our culture.

So what I'm interested in. And frankly, I don't care about building that's not the issue for me. The issue is making comprehensible very complex systems - all complex systems, meaning all the sprue of cultural endeavor are brought into the picture. So, if you could make something or think of something that engaged every aspect of human endeavor, that's what I'm interested in! And if it's a building, that's fine. Or if it's imagining it on the Internet, that's fine. I don't really care, because I don't think it really matters how it's realized. What matters to me is for there to be this craft, this culture, and this way of seeing the world that is deeply interested in manifesting, sorting out, and creating poetry to the palimpsest of human endeavor - and that's architecture.

Now, a very good way of doing it is by building, because you get some sense of the ground, some sense of organizing very large numbers of people, and organizing massive quantities of capital - i.e., what you're willing to invest in this. In the end, what you're willing to invest, that's an issue. Now it could be bags of gold, or it could be collective human endeavor. No gold, but a vision of something that has to get done. I haven't done any building designs since the Loaf House but have instead been investigating these complex organisms. These have taken form within this sketchbook, which is a depository of complex systems. Have you seen this yet?

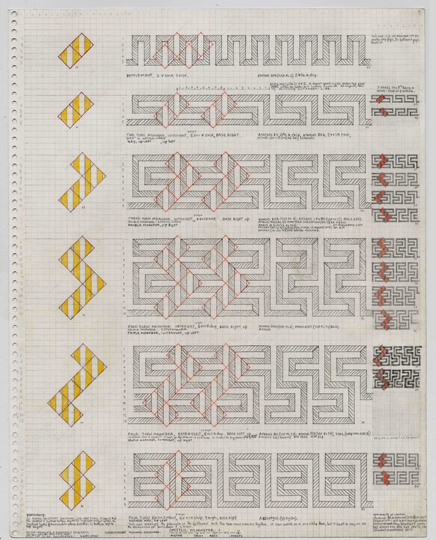

Above: Page from Nicholson's sketchbook: Meander folding, 8th cent. Greek Geometric Vase.

Images courtsey Ben Nicholson © Ben Nicholson, 2005

(26:24) Are these the sacred geometry studies?

This whole book? [a 11- by 14-inch sketchbook ]

(26:27) No, not yet"

Well, these are interlocking cosmi periods of history. [turning the page] Then very early tiling systems"

(26:37) Wow!

I'm interested in locating the holy grail of the minimum means to express the most complex ideas.

(27:01) Man, these are beautiful drawings!

Well, thank you, but I'm just interested in meditating on certain ideas, and this is the way I do it. It's the way things make sense to me. I like to draw: that's my way of thinking. These drawings, they actually take quite a long time. [Laughs] I'll spend about three weeks on a drawing like this, and all of this is drawn as independent systems. All the way out past the lines, but never across them - with all tiny little fractions that create this. I'm now writing this book that is based on different phases, systems, the relations of numbers, and things like that. For instances, like this relating to cards [Indicates elaborate drawings within the sketchbook], ways of playing poker, the poker parable, and tarot: systems of organizing the cosmos, planets, and constellations. This is the latest page I've been working is about the organization of the pantheon of the gods. Who's indebted to whom, how they are related, who screwed whose uncle or grandmother and all of that. I'm now doing another one of these on Mohammed that's the current one. This whole period of pages here has to do with the numbers one to ten and the number twelve. All qualities and how they're divided and then what the geometric constructions that allow it to happen. This whole sketchbook will be included within the final book.

This might seem to be a ridiculous thing to do, but what I'm aiming for here is to work with nothing and no matter: to have a self education or a didactic education without matter. There is plenty out there without having more. So this is dangerous talk - I'm talking heresy! I mean here you are representing the world of architecture and your talking to a heretic who's basically advocating that, to be in the world, with the world, and of the world, matter is a secondary concern. If I'm taken to the mat, I will say, at this present time, matter is still the best way to think of architecture, but I'm not so sure for very long. The computer is radicalizing the way we think about our world. I look at my kids and they're not interested in playing with Lego! They play with Lego, but they played with Lego after having played video games. They were reenacting video games with Lego. It's totally different, but they're all still playing. The great Victor Hugo line from his great novel (The Hunchback of Notre Dame ) where the book kills the cathedral is a reoccurring theme throughout culture. We are now in another phase of this. We are right in the midst of it, and you and I are taking part in it.

(33:30) Your projects commonly use a method of collage as a device to create or delve out new or imbedded meanings or realities within objects through their deconstruction and eventual reassemblage. Does this strategy of collage or "collage thinking" manifest itself as a type of narrative or mythopoesis in your work?

That's very perceptive. Although I haven't practiced collage for many years, at all! Now that's cutting and snipping bits of paper, but what collage allowed me to do was take William James' great maxim - the mark of an intelligent mind is the ability to make connections between unlike things, which is really a good line. How do you make things that are seemingly irreconcilable? Collage allows you to do that, and the medium is the beauty the eye finds in and between things. For example, joining an octopus and a banana, there will be one place where it's just like ocular orgasm. You glue it down and let it go. That is a meditative practice and has been very useful for a lot of Western art.

Left: Collages for the Teloman Cupboard from the Appliance House

Right: Drawings for The Appliance House

Images courtsey Ben Nicholson © Ben Nicholson, 2005

Those ideas have influenced this current work, especially, as you point out, in the notion of the myth: because not only are you getting these interesting connections that are visual, but also stories. You can make your own mythology out of the components, and this was Max Ernst's great contribution. Collage as a function of things that aren't allowed to get together, but are dragged together into opening and revealing new connections. Consider the whole rhizome projects since the late 1980s. I was looking at my whole Appliance House project. They are rhizomes, and I was thinking of them as rhizomes, but I had never read about them. What I was interested in the Appliance House was these long unending journeys through space that picked-up, collected, jointed, popped-up, and revealed so that the form of organization was an ever-rolling whole that would never end and was marked by and could mark discreet moments as happily as making supper in the kitchen. Your learning goes backwards and forwards - you're not always on a forward march with learning. Also, when you work at it, you'll find things that happened ten, twenty, thirty years ago, and when you address them again, you'll be able to see clearly what it is that you are doing totally. So the collage work is ever present, despite the fact that I haven't touched one in years, in the structure of thinking.

(36:57) The structure of your book The World Who Wants It? seems to have a similar "collage thinking" to it. Do you see this book as a divergent endeavor for you or coming from a similar method of creating architecture?

The making of that book was really pretty strange. In terms of the process of it, I was at a kind of a static period of individual realization which was so pleasurable and necessary to write at that time (after September 11). I was also spending half of the day writing the book and the other half working on yellow labyrinth drawings, and there is a mountain of them which I can show you. Drawing these yellow and white paths choreographed through writing, The World Who Wants It? and sadly these two books should have come out at the same time. They should have because they relate to each other. In terms of your question though, it's definitely imbedded within my past work. What I feel bad about is not having published very much in the last few years, because your references are about the past - kind of following a soap opera.

Above: Page from Nicholson's sketchbook: Labyrinths, France 13th century.

Images courtsey Ben Nicholson © Ben Nicholson, 2005

I gave a studio at UIC once which was titled "A Pizza With Everything." That was ten years ago, and even then I was trying to think of a way to bring everything into a simultaneous realm. The work I did in third year undergraduate, the Travulgar Square project, was definitely that. It's a theme that comes up over and over again. The Loaf House was once again a project to try to understand all of the facets of life and the absurdities of it in one place - where you have one object, one building, and one form. Other student journeys which were terribly important to me were Sicily, Greece, and Egypt, where I really saw these buildings that had everything in them, and that for me is where you're able to grasp what things mean. And that's the theme. So the book, The World Who Wants It? is a project that is developing a vision where you would assimilate the difficulties of Western culture into one big lump in five thousands words. It's nothing more than that.

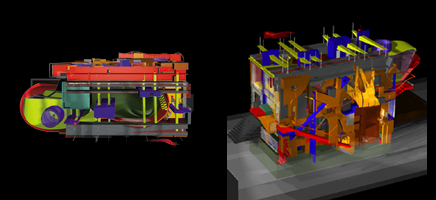

Left: Plan of The Loaf House

Right: Axonometric of The Loaf House

Images courtsey Ben Nicholson © Ben Nicholson, 2005

(39:40) Why would you, an architect, write a book of satire on the American cultural condition?

Well you know satire is fascinating stuff. It's deadly serious, and when politics begin to breakdown, generally there is a drift towards satire, because it's the only thing that makes any sense. The Irish and British, they love satire, it's a large part of our culture. The World Who Wants It? is a vision of how the world could fit together, and it's absurd, completely out of lock step! The tragedy of the book is it probably works, that's the tragedy of it, and the horror. The book is written to show that any ideal system is it's own worst enemy, and as soon as you start to implement these visions of grandeur, they just fall apart and turn into a complete tyranny.

The bit that I feel most strongly about is the part on Jerusalem, because architects, they ultimately have to address that city. If you're into thinking about architecture and you're from the West, everything is hors d'oeuvres for working to rebuild the Temple. Ultimately you're led there whether you like it or not, and ultimately empires are led there whether they like it or not. You can't escape it. You can just drift unhappily towards this vision of heaven on earth, and ultimately that is what architecture is a vision of: Heaven on earth, at it's best. So it's not really satire for me. It's a way of dealing with something that is too difficult to bear.

(41:51) From the satire I have read previously, authors tend to start with a vice or folly they wish to attack indirectly through wit and irony. In your book you use satire to attack a myriad of institutions and American cultural ideologies by juxtaposing the dogma of the three Abrahamic religions (Christianity, Judaism, and Islam) to "radically advance American values." Could you discuss the principles behind this arrangement of ideas?

After 9-11 there was a body of literature from people like Baudrillard and Chomksy who wrote very eloquently about what the hell was going on, but they didn't pitch a solution that satire enables. No one in their right mind would try to make a proposal on how to fix this problem. It's just too complicated.

The beast for me is greed. Whether you read Dante, Swift, or any of these guys, it always boils down to the same thing: the corruption of the soul. And for me the corruption of the American soul is consumerism - I sure believe it. The project in the book is to not knock the system, but to adjust whole attitudes towards the way we live, so we're not always thinking about accumulating massive amounts of stuff, but instead to, just stop and think, for just for one second about what is of importance.

The book is quite careful about going about things systematically: you have the Bilateral Peace Corp that wakes everybody up, and then you reorganize the government. It's a real vision of an American pluralism culture, and I truly believe in the idea of pluralism. I deeply believe in pluralism. I believe in the close proximity of multiple systems or agnostic systems. I think that change and a vivid nature of lions, tigers, and god-only-knows what else - whales, all coexisting, that's the model! A religious system for me is nothing more than a lion and a whale. They live in different realms. The lion is never going to meet the whale and the whale is never going to meet the lion. It's not as if there is one animal that is going to do it all, and I don't think that humans are that animal. Despite the fact that they have been spoken about in religious systems as being nature's master... I don't read it like that. I see man more as an instrument or an agent more than anything else.

(52:10) Another architect I admire, Lebbeus Woods, talks about architecture as a political act, that "the practice of architecture today is protected from confrontation with changing political conditions in the world within a hermetically sealed capsule of professionalism." What are your feelings on the intersection of architecture and politics in terms of The World Who Wants It? and your work in general?

Yesterday at IIT, we had an interesting luncheon, one of those sort of traveling lunches. The chancellor of the school challenged the dean of architecture to imagine the best graduate school initiative. So a bunch of friends and colleagues down there sat around imagining what it would be like. A question was brought up about getting into housing. It was like IIT should really get into housing, and I thought 'okay fine,' but there was a bigger question out there to answer that finally came up. You can't talk about housing until you have a politic of how human creatures are going to be collectively taken care of.

The question of housing is stupid until you've made your peace with that question - it's stupid. So is the idea to give everyone a kitchen, bathroom, a room for the kiddies, and a room for mom and dad to fuck - the modernist dream is stupid unless you ask political questions. Like who is going to get the house? Under what circumstances are they going to be given it, and is it a collective responsibility for a culture to make certain that a human has warmth at night or not? Till you ask those questions, housing is stupid. So it is definitely political, and in the satire, of course, I deal with the issue of housing. The number of people in cities throughout the world, use a completely different type of system than is currently being delivered here, and until you ask those political questions, you're just blowing in the wind. It's a beautiful thing, politics are beautiful, and they're there to enable a community to live collectively with one another. It's not about stabbing each other in the back; it's about enabling people to reach their dreams and pursue happiness, about making room for people to participate. Religion is deeply bound up with this thinking. We also had a discussion about bringing a course on politics into the school. It was a wonderful conversation about how to illustrate to architecture students where they can be effective and how they can be effective in the world.

Creative Commons License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License .

/Creative Commons License

7 Comments

what an amazing interview - cheers to you! More of this if you can, would love to see an interview from each of the cranbrook crew that he mentioned - along the lines of this one

does he still have the bread loaf tag collection?

I've been to his lectures, and they are amazing. He has a billion things running through his mind a second, and his ideas and concepts are simply awesome to listen to.

BEN NICHOLSON, I think, is foremost a great teacher.

His thinking is creative and architectural,

in my eyes, a better teacher than many "builder-teachers".

British humour and British brain combined with American wideness of thought.

(enough adulation...)

its amazing a guy this brilliant didnt get tenure at iit -- says alot for that school!

Fantastic, mind-blowing,hungry for more...will definitely read up more on this brilliant mind

Ben, Thanks for the memories. Especially about Tony Gwilliam. Yes I heard the AA story before. I knew Tony and Charlene when Tony taught at SCIARC. Then Tony and Charlene lived in Ojai, CA for quite a while. Tony Gwilliam is now living in Indonesia. I always thought highly of Tony's work. His latest is a zen mantainer, easliy built and transportable.

Just curious, why the strikethrough the word Architect at the beginning of the intro? Somebody give Archinect a hard time about calling him that? I'm assuming he's not licensed and that's why, but I'm wondering if people are so obsessed with this issue they make a fuss over its use here.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.