Think bank architecture and its associated headquarters and you may find yourself stultified by visions of doric columns, artless atriums, and bland corporate highrises. However, these six structures by prominent practitioners are a survey of the unusual and intriguing. Here’s what each financial institution says about its social/historical context, as well as the role of money at that time.

Bank of Scotland (David Bryce, 1864-71)

The Bank of Scotland, founded in 1695, was revamped in 1864 by architect David Bryce, whose legacy is his refinement of the Scottish Baronial style. The Bank of Scotland is designed chiefly in an Italianate classical style, squeezing in a few decorative Ionic columns on the upper storeys and some figurines up top. It’s linear, imposing, and made of brick, but curvy enough not to be mistaken for a garden variety Italian bank. In its 19th century Edinburgh context, this bank is stylish yet secure, a tie to the past with enough flourishes to set it firmly in its own present. Money here is being guarded by the officially appointed, but the architecture signals that the officially appointed are a little hipper than their strictly classical predecessors.

Frank L. Smith Bank (Frank Lloyd Wright, 1905)

A little over forty years later, Frank Lloyd Wright rejected everything classical about bank design with the Frank L. Smith Bank in Dwight, Illinois. Stripped of flourishes with no overt references to Italian columns or the imposing bulk of classical banks, the Frank L. Smith bank was instead designed not only as a financial institution, but also to the buck isn't stopping here, it's just recharging before heading out again serve as a meeting place for the real estate clients of its namesake local agent. As a result, the building is simultaneously inviting and secure. It has a fireplace and skylights, and was designed initially as two rooms (one for the money, one for the offices). Frank Lloyd Wright’s entire game-changing oeuvre, which focused on introducing powerful, vibrant geometric forms into the closeted Victorian era from which he sprang, is evident here. In early 20th century American terms, this abandonment of the classical for a pragmatic and (relatively) unornamented architecture was striking, especially when contrasted with the then recent Beaux Arts movement. This is money that is unafraid of making new statements and exploring new frontiers: the buck isn’t stopping here, it’s just recharging before heading out again.

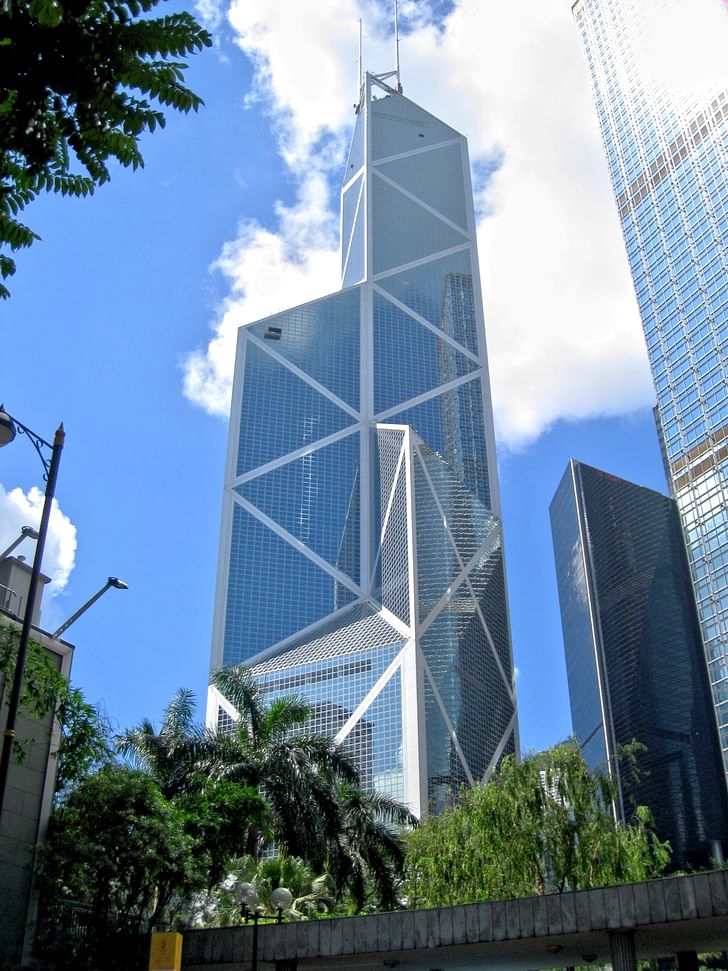

Bank of China Tower (I.M. Pei, 1990)

In 1990, Hong Kong was still part of the British Empire, and the official handover to Chinese independence was seven years away. I.M. Pei was brought in to design a bank that would reflect this particular moment in history, incorporating a respectful nod towards Britain while also encompassing China’s hopes for the future. The resulting asymmetrical, glass-facade,Pei succeeds in creating a bank building that both breathes yet provides a feeling of stability diamond-latticed tower is an arresting visual addition to the cityscape that incorporates nature by reflecting clouds; at the street level, a series of columns references the West while simultaneously providing structural stability for the typhoon-prone region. I.M. Pei, whose canon could be described as imbuing a light touch to projects of enormous scale, succeeds in creating a bank building that both breathes yet provides a feeling of stability. As no one knew precisely what shape the economy would take after China regained control of Hong Kong, from an architectural money perspective the bank is a reflection of a hopeful yet flexible approach to the future of 21st century commerce.

DZ Bank Building (Frank Gehry, 2000)

Incorporating a no-nonsense, rectilinear exterior with a very playful, sculptural interior (the “Horse’s Head” serves as the bank’s conference room) the DZ Bank Building by Frank Gehry serves a combination of masters. It’s partly a bank, partly a suite of private residences, all positioned within pointing distance of Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate. This joining of seemingly disparate programs is perhaps reflective of the then relatively recent fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, in which the stringent east and liberal west sectors of the city were unified after a multi-decade separation. Structurally, this blend reflects the powerful German economy and its low tolerance for financial tomfoolery, while allowing for a more adventuresome (if heavily fortified) investment spirit for the upcoming century.

Rabobank Westelijke Mijnstreek Advice Centre (Mecanoo, 2014)

In an era so postmodern there’s not even an encapsulating term for it, multinational firm Mecanoo purposefully designed a bank for Rabobank that would not look like a bank, thus upending any notions of classicism, narrative, or historical context. With no tangible object to house, why constrain the architecture?The result is an open-plan, natural-light infused, purposefully undefined space that intermixes extemporaneous work spaces and striking staircase views. Money-wise, this bank is fundamentally about the shift from tangible money to a financial world whose transactions are largely digital. With no tangible object to house, why constrain the architecture?

Intesa Sanpaolo Skyscraper (Renzo Piano, 2015)

Although detail-lover Renzo Piano appears to have designed a straight-up return to classic bank architecture form with the Intensa Sanpaolo skyscraper, the building is more of an ecology than a straightforward programmatic fulfillment. The building is more of an ecology than a straightforward programmatic fulfillment Piano has incorporated a suspended auditorium, a public restaurant, and a bioclimatic greenhouse within his design. Fittingly, the bank is located across from Turin's Mole Antonelliana, a 19th century project that came into being only after multiple groups pitched in to fund it. The Intesa Sanpaolo isn’t just a bank for finances, but also one for knowledge and the preservation of natural resources. Bankers, this structure seems to say, are no longer simply responsible for money in an era of globalization; they must consider the far-reaching consequences of their actions.

Looking for more to bank on? Check out the other pieces included in Archinect's special March 2016 theme, Money.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.