“We took all the 911 phone calls – because this is all we know, I mean everyone is conjecturing and everything, but this is all we know – and we animated them,” explained Michael Licht, co-founder and executive producer for the Emblematic Group, sitting in his Santa Monica laboratory. Helmed by Licht and the journalist Nonny de la Peña, the Group has pioneered the use of virtual reality technologies for journalism, using original audio and other information from real events as the source material for virtual reconstructions.

“So you go from apartment to apartment as people are panicking and looking out the window and you hear from their phone calls what's happening,” he continued, describing the Group’s recreation of the night Trayvon Martin, a 17-year old African American, was shot by George Zimmerman in a Central Florida gated community, reconstituted from 911 calls. “This is really what happened, this all we know: this person was yelling out this window, that person was yelling out that window."

Licht, who studied architecture before becoming a video game designer and then a journalist, translated the physical origins of these calls into virtual reality environments. Each apartment iterates off the same floor plan so, while his team did not have access to the units themselves, they were able to reconstruct their basic spatial qualities. Later, animations were created to populate the virtual spaces and the audio was superimposed. This is really what happened, this all we knowWhen viewed as a finalized project using a virtual reality headset, the constituent elements – the audio, the virtual spaces, the supplemental text – together combine to evoke a startling amount of both pathos and realism, the latter in surprising defiance of the rather clunky aesthetics of the animations, which recall video games from the early 2000’s.

"You know that feeling you get when you're around a fight or something?” Licht asked. “Something uncomfortable is happening. You go to these apartments and you witness this and how they react and you sort of get that same feeling."

Martin’s killing has a unique architectural, and socio-economical, setting. The housing development where Martin was shot was marketed as “an oasis where nobody could park a car on the street or paint the house an odd color." Then the housing crisis struck, the developers filed for bankruptcy, and the value of homes in the area dropped by more than 50%. Investors started to rent their units rather than try to sell them and the demographics of the community began to change, diversifying both racially and economically. An increase in crimes was reported.We like to maintain journalistic integrity as much as we can

But Licht is more concerned with those eight phone calls because he is, in addition to a designer, a journalist. “We like to maintain journalistic integrity as much as we can, but because it's not the actual moment I'm always hesitant to say it's a recreation,” he told me. “It's our best interpretation of the information that we have.” At the same time, the work only makes sense so long as it can carry a narrative. So, through text and audio, the Emblematic Group stitches together recreated events to make a compelling point – the same as a newspaper article, essentially, just accessed through wired goggles, played out in the realm of immersive virtual architecture.

"Humans have long been able to immerse themselves in other worlds, through oral story or novels, painting, photographs, television, cinema and pure imagination,” states the co-founder of the Group, Nonny de la Peña, on their website’s mission statement. “The mind does not travel alone – the body most certainly comes along for the ride." The mind does not travel alone

In their own words, the Emblematic Group seeks to “fully transport” viewers to virtual worlds – a task that requires not just advanced technology, but also a heightened understanding of how spaces are constructed in the physical world. “We immerse our audiences in the story, making them feel like they are in the middle of the action,” their website states.

At its heart, the work that Licht and his coworkers make attempts to deal with a fundamentally architectural issue, albeit one different than those described above: how to communicate, as faithfully as possible, an event that took place in a particular space, at a particular time, and to a particular person. For Licht and his coworkers at the Emblematic Group, emerging virtual reality technologies potentially offer one of the best ways to tell these true stories with both affect and honesty.The work that Licht and his coworkers make attempts to deal with a fundamentally architectural issue

“The black tape on the floor shows you how far you can walk,” an employee explained while fitting me with one of the bulking VR helmets. “But you’ll be able to tell inside the simulation.” When the simulation began, I was confronted by a large white matrix that quickly materialized into a streetscape. Arabic signage appeared, and I had been told I was meant to be in Syria. I walked around a bit, and, as I neared the edges of the simulated world, a transparent grid momentarily flashed, warning me that, in “real life,” I was approaching the black tape.

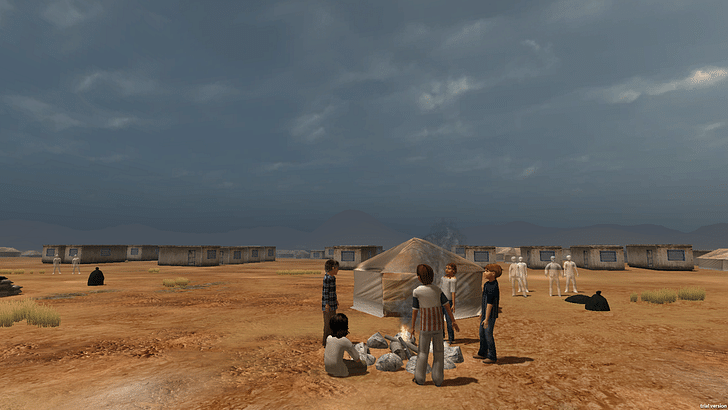

I swiveled my head, and a little girl stood on the sidewalk in front of me, humming to herself. Suddenly, a loud crash sounded and the screen filled with dust and smoke. I’m sure my mouth was agape, although, at the moment, I was pretty unaware of my own body, focusing instead on the limp, pixel-based form of the little girl that came into view as the dust settled. I was pretty unaware of my own body, focusing instead on the limp, pixel-based form of the little girl that came into view as the dust settledThen the scene changed, fading to white, and I was in the midst of a fight at a food depot in a refugee camp. It shifted again, and I was in a large field. White tents popped up all around me, alongside vectors of human bodies, also white and translucent, serving as stand-ins for the rapidly-increasing population of refugees produced by the civil war in Syria.

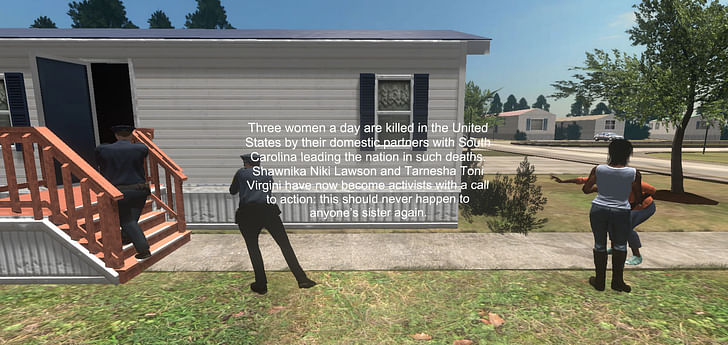

Later Licht showed me a work they made about a domestic violence case, a husband who murdered his wife, that had taken place in the American South. After I had experienced it with VR goggles, he showed me comparisons of stills from their project and the actual crime scene photos that had served as a reference. Here was the room I had just occupied, a bit clearer and more detailed, but disturbingly similar. Hanging above the stove was the same green oven mitt. Above the couch, the same decal: curling scripts spelling out “Family is forever.”

The feeling produced by VR isn’t really like watching a movie. Knowing the virtual experience was a simulacrum did not diminish its affecting quality – it enhanced it, as if, simultaneously, I could register the actual, documentary evidence (the sounds, the referents) and also project on to it, the way one might with a painting, for example.Knowing the virtual experience was a simulacrum did not diminish its affecting quality In a sense, it’s like inhabiting an architecture rendering – and, in that, suggests pretty significant opportunities for architectural representation that could communicate far more than the HD videos that are currently in vogue.

More than anything else, the affecting quality of VR journalism seems to be rooted in its ability to immerse the viewer in a three-dimensional space, eking out the viewer’s feeling of agency in the virtual reality. Feeling inside of an event that the viewer knows has actually happened, implants an unusual degree of investment in the issue.

It’s this three-dimensionality that also makes a VR experience seem most architectural – although it’s not really a big stretch to say that a virtual space is intrinsically architecture, plain and simple, since it’s designed in much the same way as a brick-and-mortar space and almost exactly the same way as the models and renders that now automatically precede just about any physical construction. In short, a virtual reality experience is architecture plus narrative – or, in the case of the Emblematic Group, plus journalism. But with this added capacity, the creator of a VR space has far more control over the spatial experience than an architect ever could, determining precisely the very borders of a world and, for the most part, how you move around it. It’s a speculative architect’s dream medium and, at the same time, an incidental exposition of the natural, and likely fortunate, limitations of building in physical reality.In short, a virtual reality experience is architecture plus narrative

These days, there’s a growing contingent of architects who try to deploy the many strategies and tools developed by the discipline for purposes outside the realm of spatial production and physical construction. It makes sense: the sensitivity to details, among other things, required in design has a wide-range of other possible applications. Particularly in this increasingly urban and spatially-complex world, architectural thinking can serve as a tool to decode and interpret the particularities of events – acts of violence, trauma, crime – that occurred in, and were therefore informed by, an architectural context. But for the most part, while this “architectural toolkit” is incredibly useful for analysis, it often produces outputs such as maps, texts, diagrams that can fail to telegraph an event with much affect or emotion. Paradoxically, the affective capacity of built architecture is among its most noted attributes. In the work of the Emblematic Group, these two modes of understanding – the descriptive or journalistic and the affective – start to emerge merge. VR presents a way of translating the architectural or spatial context of a traumatic event without edging into dry, overly-analytic territory. Through the opaque lenses of a headset, architecture becomes not just the setting for a story, but also its material.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

1 Comment

Emblematic's work is charming, reminiscent of the pioneering virtual-worlds development at USC's Institute for Creative Technology in behalf of the US Army, Mechdyne's immersive environments, and my own virtual design industrial studio, Worldesign Inc., first of its type. Urban planners now use these methods regularly, which speaks well for virtual worlds' use within the constraints of professional practices.

The issue with using such interpretations for journalistic purposes -- and this is true of all journalism, in print or virtual environments -- is its ultimate source: human beings. With unique mental frameworks, perspectives, and agendas. These overlay the reality being "journalized." When we participate in a constructed virtual world, we are experiencing reality through yet another layer of cognitive and ideological gauze. So far, the inevitable mismatches between the worldbuilders and world-experiencers has intervened to seriously reduce the value of "VR" as a journalistic medium.

William Gibson had quite a lot to say about this in his groundbreaking Neuromancer future-history series circa the late 1980s and 1990s, as did Neal Stephenson in his epic novel, Snow Crash. Perhaps this discrepancy will change with time as human experience in general becomes more manufactured and congruent -- an event not yet on the horizon.

-- Robert Jacobson, PhD, editor, Information Design (MIT Press 20001) and VR veteran

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.