Few would have predicted that a “used-condom-strewn” elevated railway line running through what used to be seedy Chelsea would become one of New York City’s biggest cultural attractions. And yet, according to Elizabeth Diller in conversation with Los Angeles Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne at LAX Art on February 16, last year over seven million people walked Diller, Scofidio + Renfro’s High Line. That’s about four million more than attended MoMA or even all of the Yankees games, making The High Line not just a renovated railway, but a literal cultural bridge between the pedestrian and the aesthetic realms.

Although it would be a stretch to say the room was packed – patches of empty chairs, like vegetation on the titular project, broke up the audience of graduate students, coiffed designers, and overall-wearing high school art teachers – those in attendance were rapt as Elizabeth Diller meticulously unwound the political and logistical challenges of creating The High Line. The concept behind the project originated as far back as the 1980s, with Steven Holl casting his eye upon the then fenced-off railway and imagining a place with bookstores and cafes. Holl wasn’t the only one who was interested: according to Diller, a graphically savvy PR campaign, led by “Friends of the High Line” founders Joshua David and Robert Hammond, employed a certain amount of Hollywood salesmanship to drum up public support for the revitalization of the structure. (Ironically, property owners at the time were advocating for its demolition.)

Despite David and Hammond’s winning neon green letterhead, however, the process was fraught. The High Line was slated for destruction under the Rudy Giuliani administration, receiving a last minute reprieve only when Michael Bloomberg was sworn in as mayor. From there, the challenges to transforming the High Line were both legal and conceptual. The High Line’s program is “temporary,” according to Diller: one of the city’s conditions for development stated that the structure should remain convertible into a functional railway. With two exceptions – The Standard Hotel, and Neil Denari’s High Line 23 apartment building – the air rights prevent anyone from building over the track (the pre-existing overhangs have been preserved, and in one case, turned into a sound installation).

Zoning headaches aside, DS+R’s biggest battles focused on creating not just an extension of the street below, but rather “an otherworldly realm.” DS+R rejected Holl’s initial vision because it featured too many recognizable elements that one would find on the street. The designers fought against stakeholders Zoning headaches aside, DS+R's biggest battles focused on creating not just an extension of the street below, but rather "an otherworldly realm."who wanted to insert stairs or elevators at each block to create exits for the same reason: this was supposed to be a pathway that would meander for blocks at a time without a clear exit or entrance in order to foster that otherworldly vibe. Likewise, the distinctive paver pattern of The High Line, which alternates pedestrian pathways with clusters of vegetation, was purposefully designed not only to mimic the natural clumpy distribution of foliage that existed before the renovation began, but also as a solution for the extreme narrowness of the track. At one point, there were rumors that different sections of The High Line would each be designed by a different architect, an aesthetic nightmare which DS+R and landscape architects James Corner Field Operations were able to happily avoid.

Throughout the evening, Christopher Hawthorne’s skill for structural conversational moderation was somewhat muted. Although he provided broad strokes at the outset, foreshadowing the “heroes and villains” of The High Line, he was largely content to let Diller unspool her narrative, occasionally prompting her to elaborate on certain aspects of the story. At one point Hawthorne was able to riff a little on “uncovering the infrastructure” of cities, making a brief comparison of the design process of The High Line to the innumerable possibilities of remaking the Los Angeles River, but his meditations were swiftly steered back to the topic at hand.

For Diller, an enormous part of the joy of the project wasn’t just in its conception and making, but its unanticipated aftereffects. Commenting on image that showed a group of visitors lounging on The High Line’s sunken overlook, a glass partition framing traffic on 10th Avenue, Diller delightedly noted that the function of The High Line had in many ways become the “rediscovery of doing nothing.” At the very least, the corresponding slides seemed to support It is the unpredictable, elevated experience of the city – its people, its mores, its rapidly changing urban fabric – that forms The High Linethe rediscovery of people-watching: Diller showed an image of a naked exhibitionist in the Standard Hotel, standing unabashedly in front of his hotel window in clear view of pedestrians below, as well as a couple having some window-based sex. Another slide featured an older, pant-suited woman lounging on a bench in the sun against a backdrop of a steamy leather pants ad.

Before the evening wound down into a book signing for the accompanying Phaidon text, “The High Line,” Diller lamented the fact that she and husband Ricardo Scofidio had neglected to buy any property in what is now an incredibly valuable tract of real estate. (This value isn’t just limited to New York City: Diller noted that the project’s popularity has spawned numerous knock-offs in other cities, some of which have built conceptually tone-deaf, free-standing sections of track as a kind of blatant tourist draw.) In keeping with its organic mutation, The High Line continues to grow and change: Diller noted that there are new spurs on 10th Avenue in development, as well as DS+R’s modification of a public plaza extending The High Line on 18th street.

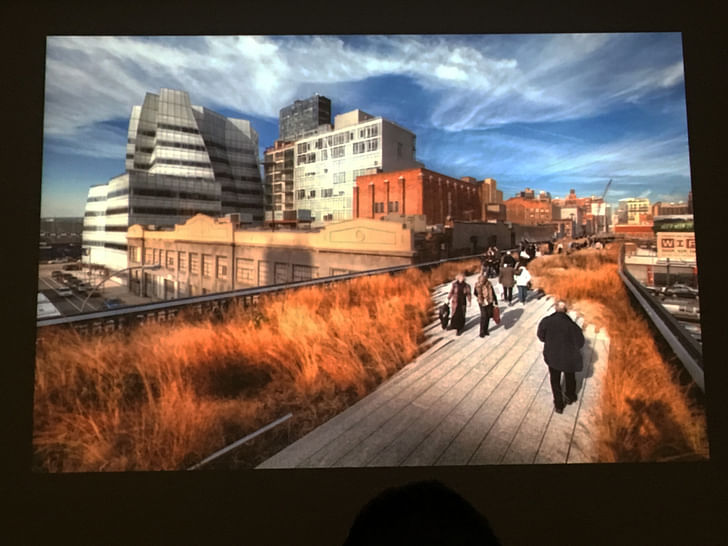

Perhaps it is this perpetually evolving quality that underpins the project. The contrast of copper-colored, dead grasses against the almost snowy facade of Frank Gehry’s IAC building forms a gorgeous and unlikely urban wilderness, but it is the unpredictable, elevated experience of the city – its people, its mores, its rapidly changing urban fabric – that forms The High Line.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.