The Deans List is an interview series with the leaders of architecture schools, worldwide. The series profiles the school’s programming, as defined by the head honcho – giving an invaluable perspective into the institution’s unique curriculum, faculty and academic environment.

For this issue, we spoke with Amale Andraos, Dean of Columbia University's Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation in New York City.

One year deep into her deanship at Columbia, Amale Andraos has set out to extend her far-reaching connections within New York’s architecture world to strengthen the school’s relationship with the city and beyond. After succeeding Mark Wigley as Dean last fall, Andraos has set up a paid internship program for current students, and will launch New Inc. this year, a mentorship program for GSAPP alumni at the New Museum. She also currently serves on the board of the Architectural League of New York, and as a faculty advisor on the steering committee for Columbia’s Middle East Global Center.

Back on campus, Andraos has sought to rethink the literal architecture of the studio environment at the school, and continue fostering interdisciplinary collaborations between GSAPP and other disciplines. Alongside her role as dean, she also runs WORKac in New York City, the firm she co-founded in 2003 with her husband, Dan Wood.

Briefly describe your own pedagogical stance on architecture education. How would you characterize the programming at your architecture school?

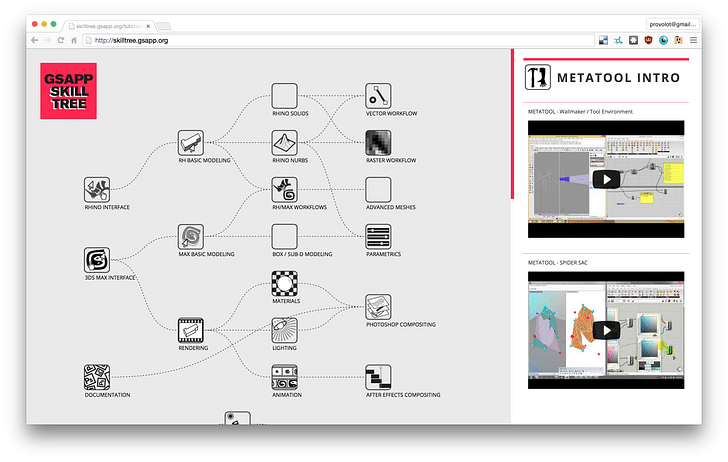

What I find most exciting about architectural education is that it needs to be at once disciplinary, professional and totally open and open-ended as it engages and shapes the expanded field of architecture. If I think of Columbia GSAPP’s history, it has always fostered an experimental mode of education where radical discourses on architecture and the freedom to re-imagine what architecture can be is combined with the highest level of design expertise the only constant at Columbia is change. That is what I believe architectural education should feel likeand critical thinking, cutting edge skills and the newest technologies. This has produced many new forms of scholarship, knowledge and practice, which the school has become known for. It’s a thrilling environment to be in and I like to say that the only constant at Columbia is change. That is what I believe architectural education should feel like: liberating in its destabilization.

What kind of student do you think would flourish at Columbia, and why?

I am sure every dean feels that their school attracts the most interesting students, but certainly I feel very strongly that this is true of Columbia. Our students are independent, endlessly curious and imbued with a particular "street smart" character, which makes them very entrepreneurial. They are urbane, coming from all over the world, and believe in a diversity of perspectives and approaches. This makes teaching at the school very exciting, unexpected and challenging in the most productive and creative ways. Our students are ready to take on the world and Columbia is there to create a vibrant context in which they are given the skills to design but also the skills to frame the questions which will allow them to shape their future and the future of architecture and cities.

What are the biggest challenges, academically and professionally, facing your students?

Academically, the biggest challenge is how to connect things: our students want to contribute in very active ways to the shared environmental and social concerns which will affect their future not only as architects but as citizens of the world. At the same time, they are interested in architecture as architecture – form, shape, materials, technology – and want to make beautiful things. How do we bridge ethics and aesthetics? How do we bridge scales of environment? How do we make our new globalized urban context in a time of climate change visible in ways that enable us to act? How do we bridge discourse and practice? How do we teach architectural history? All of these are challenges, but also great opportunities to open up new possibilities for architecture and architectural engagement. This moment must be one of convergence, and Columbia is fostering intersections as we reassemble our curriculum and all the activities in and around the school in new ways.

Professionally, there are so many different trajectories our students encounter while at school and as soon as they graduate. It can be challenging to know where to go, what to do and who to become. Some of our students want to build, and they do very well in strong design firms, but others want to connect the dots in a different way. One of the new initiatives we are launching this fall is our incubator space at New Inc. at the New Museum for our recent alumni, to create a different transition between graduating and finding one’s "path." The intent is to further extend and support the explorations of new forms of practice and the question of what entrepreneurship – as intersection between art, architecture, new technologies and the city – can mean for architects, architecture and urbanism. Interestingly our student-founded publication Colon is thinking of investigating this new space, and so this would be a great example of fostering an intersection between new forms of practice and discourse.

How do you provide for employment after graduation?

There is an informal and a formal way: because we are in New York and much of our faculty is practicing in the city, there has always been a natural mentorship loop where students intern and then work with their studio teachers. In addition, our global network of Studio X is increasingly allowing students to connect to alumni in those cities.How do we bridge ethics and aesthetics? How do we bridge scales of environment?

I am adding a more formal process as well: this fall, we are launching an internship program where students – US and international – can have paid internships and get credit. We have a newly activated career services office, which not only connects our students to alumni but also organizes its own lunchtime conversations, often initiated by students. We have a new alumni mentorship program as well as a big career day where diverse practices meet our students; we organize portfolio reviews with many great architects and designers from around the city and as I mentioned above, our new incubator space at the New Museum is going to support our recent alumni at the heart of the growing technology industry in the city.

How do you familiarize yourself with trends within the architectural profession/academia, and adapt these observations into programming and student policy?

I follow Archinect of course! Our faculty and students are quite connected: the latest approaches and trends tend to bubble up within seconds, and our faculty leads many of them. But the more important question at this time is how to move beyond the echo chamber and articulate shared concerns and possibilities for intersection?

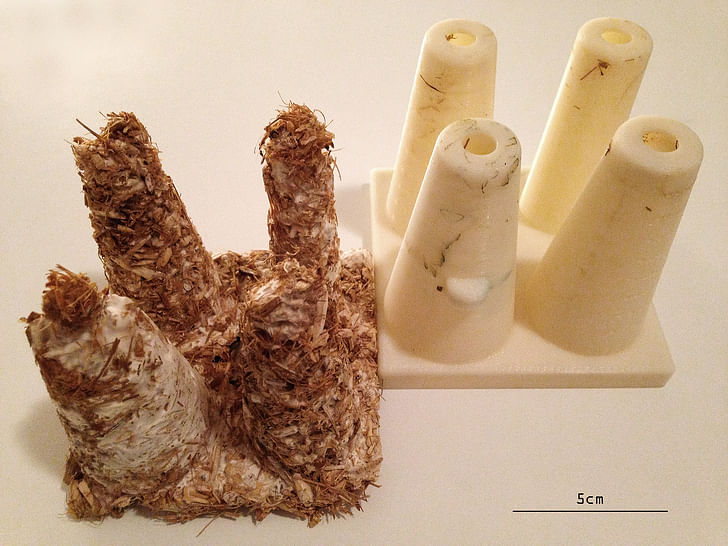

We are experimenting in two structural ways: first, by rethinking how we organize ourselves spatially. The idea of the architectural studio hasn’t changed since its inception and after analyzing the long-gone premises it was founded on, we have redesigned it quite radically in an iterative process with the students and faculty. Each studio section now has a long collective table for computers, a shared table for making and meeting, storage towers for models and materials as well as large screens around the room. The result is a very open space where dialogue, exchange and collaborations across the studios have increased dramatically.

The second change has been to the structure of the schedule. In order to find intersections between the individual studios and move beyond the parallel tracks of the curriculum – design, history theory, technology, visual studies and professional practice – as well as create connections to the other programs at the school, we have carved a two-hour slot within studio time for what we are calling "transfer dialogues" to create a shared context and allow for new lines of inquiry to emerge.

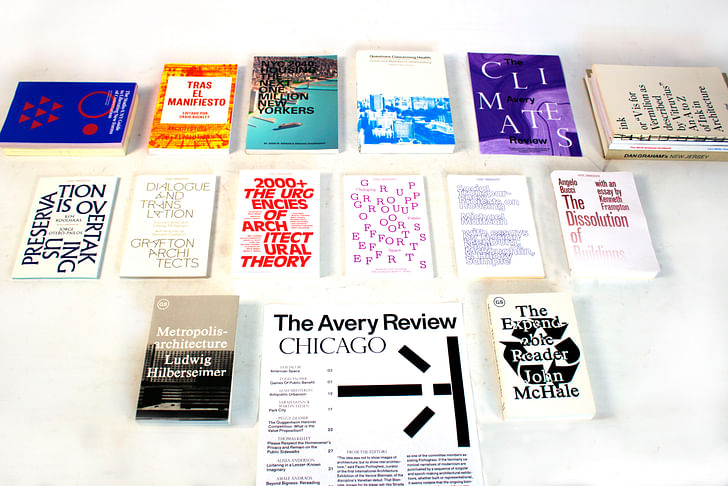

Finally, the school is actively producing new forms of design research and scholarship through our publication office, the Columbia Books on Architecture and the City and the Avery Review, as well as through our exhibitions at the Ross Gallery, both of which will be represented at the Chicago Architecture Biennial. The Buell Center (which will also be present in Chicago), the Center for Real Estate (CURE) and our new Center for Spatial Research have acted as great connectors among the programs, as well as between the school, the university and the city, as they articulate themes around which new forms of scholarship are emerging – on the question of housing, on climate change, design and policy, on migration patterns. Our faculty is actively engaged in shaping both practice and discourse in the field and our students are encouraged to do the same.

Do you collaborate with other departments or schools when designing programming?

We have many programs in addition to Architecture: Urban Design and Urban Planning, Historic Preservation and Real Estate Development, along with our Critical, Curatorial and Conceptual Practices (CCCP) and PhD programs – and collaboration opportunities have increased, whether through joint design studios or seminars, joint lectures and symposia or joint degrees. Starting this fall, we are reserving a slot for all the cross-program seminars on Friday mornings. As a result, the boundary between the programs is becoming increasingly fluid.

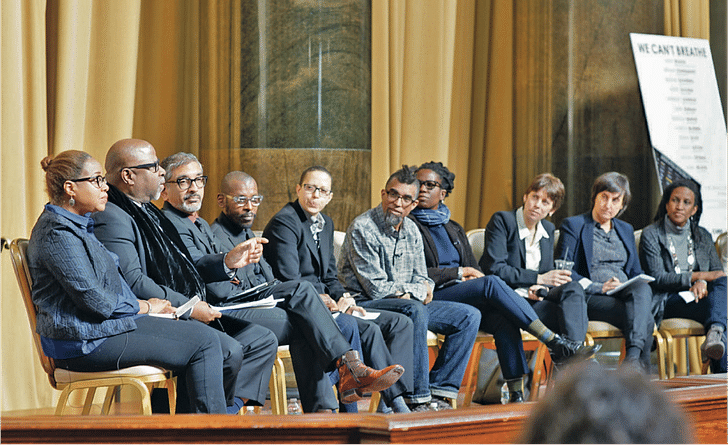

The School is also increasingly collaborating with other schools and centers on campus such as the School of the Arts and the Earth Institute. This December, for example, we are hosting a major symposium on climate change, which will bring together scientists from the Earth Institute with humanities scholars and historians as well as architects. Architecture has always drawn together science and art, and the School has the potential to bridge the conversation between the humanities and the sciences at a time of increasing divide.the School has the potential to bridge the conversation between the humanities and the sciences at a time of increasing divide.

In New York, we collaborate with cultural institutions such as MoMA, the New Museum, the Architecture League and the Center for Architecture. And globally, our Studio X network has allowed us to make exciting connections that have become integral to the school’s ecology. Last spring we hosted a conference entitled "Housing the Majority" organized by the Studio X directors, which brought together scholars, architects, artists and activists from Rio, Mumbai, Istanbul, Johannesburg, Angola, Cairo and Amman. Even though everyone was coming from around the world, it felt quite intimate, as if amongst friends.

What is the relationship between the school and local government?

Our faculty is engaged with the City of New York on many levels, whether through City Planning or the Department of Design and Construction’s Design Excellence Program or the Housing Authority; the school is always home to active city officials with whom we have an ongoing conversation. Columbia’s continued engagement with the real is very important around the world as well, and this translates to the relationship we have with the cities of Rio, Mumbai or Istanbul, for example. We have had great success in engaging cities very seriously while also maintaining the freedom to explore, project and imagine, and our students seem to negotiate this line very skillfully.

How would you like the school to have changed in your tenure?

Columbia has always felt like home, because of its incredible diversity and intellectual generosity. I want to preserve that. As for change, I don’t want the school to change as much as I would like it to open up new possibilities for thinking and practicing architecture as well as for imagining the future of cities and the environment. But as Joe Strummer said “the future is unwritten…”

How important is it for an architecture dean/director to be, or have been, a practicing architect?

I don’t believe that it is important for a dean to be a practicing architect, but to be an architect who supports practice as well as discourse, to foster a space for design and debate.

How do you manage the school’s personality in the eye of the public? If there is one school whose personality doesn’t need management, it’s Columbia. I don’t have to manage it: I just have to make it visible and then allow it to grow.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

2 Comments

zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz

That gif diagram is so 2015

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.