The Deans List is an interview series with the leaders of architecture schools, worldwide. The series profiles the school’s programming, as defined by the head honcho – giving an invaluable perspective into the institution’s unique curriculum, faculty and academic environment. For this issue, we spoke with Kenneth Schwartz, the Dean at Tulane University's School of Architecture.

Before Hurricane Katrina, the 121-year old Tulane School of Architecture was primarily concerned with architectural design, not necessarily progressive community-oriented design projects. Since the 2005 disaster, the school has changed its focus to encourage its approximately 300 students to become actively involved in the design issues of the surrounding community, resulting in a hands-on approach that immerses students in the often thorny problems of the wider world. In New Orleans’ case, architectural students must grapple with building in historically impoverished neighborhoods that have also not fully recovered from the effects of Katrina. Kenneth Schwartz, who has been at the school’s helm since 2008, has made Tulane synonymous with a pedagogy that integrates the theoretical and the pragmatic.

Archinect: Briefly describe your own pedagogical stance on architecture education. How would you characterize the programming at your architecture school?

Kenneth Schwartz: At the Tulane School of Architecture we operate in the intersection between disciplinary knowledge in architectural and urban design and direct action through design engagement within the community.

Architectural pedagogy should focus on educating students in the abiding cultural and social roles of architecture and related fields by providing a well-rounded, humanities-based education with discipline-specific coursework that serves to prepare future professionals in design, building technology, theory and professional concerns, with an emphasis on critical thinking. At Tulane, we seek to instill a sense of responsibility and ethical conduct in our students through civic engagement. We provide our students with tangible experiences that yield an understanding of both the possibility and limits of design as an agent of positive social change.

What kind of student do you think would flourish at your school, and why?

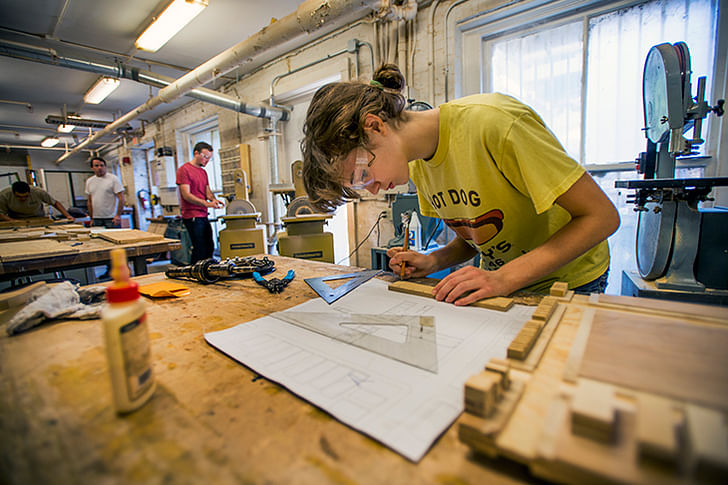

Students who come to the Tulane School of Architecture have opportunities that go beyond most other schools of architecture in bringing their talents and compassion to bear on real issues of the community. Students who flourish at our school are interested in hands on experience – with clients, community groups, at various scales and with diverse project types, from visioning of urban and landscape issues for a neighborhood or infrastructure intervention to small-scale design/build projects. Students at Tulane succeed bringing their inherent curiosity with a willingness to explore spatial ideas through a rigorous iterative process, and an awareness of the complexity and interconnection of architectural ideas. Three-dimensional reasoning mixed with critical thinking is something we see in successful architecture students in general (certainly not unique to our school).

What are the biggest challenges, academically and professionally, facing your students?

Architecture as a profession is at a curious and contradictory moment. In one sense, the educational model has never been more relevant in providing experiences that can lead a student in many different professional directions. While the educational model is also very effective in positioning graduates to enter the “traditional” field of architectural practice, there seems to be a continual diminution in the power and potential of that track in contemporary society. We view the entry into “the profession” in a far more diversified and entrepreneurial way than many other schools.To be sure, while there will always be graduates who excel in the normative conditions of practice, society seems to place less and less value on this track – as evidenced by the way so many firms have diversified in their practice models over the last twenty years and the financial challenges faced by some practitioners.

When a profession is being pulled from its center to areas that were once considered the margins, there can be questions about the perceived value of education that may seem largely similar to the one that has existed for the last fifty or more years at many institutions. Added to this are the particular characteristics of the millennial generation. Among the high achievers in this group, the ones who are dominantly positioned to study in our schools of architecture, these young women and men have been “successful” in everything they have done, yet they have not necessarily focused with real dedication and sustained attention on one area of exploration. Traditionally, great students of architecture, like many great architects, are persistent and intense in their desire to develop their ideas over the course of a semester, a full five years, or over an entire career. There may be something of a culture shock that is even more jarring for this generation, yet we continue to attract students who approach their studies with genuine curiosity and ambition to develop their talents and intellect in ways that can produce compelling architectural projects.

How do you provide for employment after graduation?

Tulane School of Architecture has made great efforts over the last seven years to provide proactive and diverse support for students in their career development plans. The professional practice course serves as the foundation of this effort and was renamed and re-themed as “Professional Practice and Ethics: Designing Careers.” I co-taught this course in the first year with a young architect from a top firm in New Orleans (she continues to teach the course today). The curriculum is structured to highlight the ways students can approach their education as a laboratory to test, develop and define their professional persona, in a very real sense, based on the range of practices that architects have been pursuing over the last twenty years or so, as well as speculation about the future directions of the profession. This initiative also includes a series of focused workshops that have empowered students in more effective ways when they begin their work in various kinds of firms. Many law schools have done this very well. In some ways, I have modeled our approach on watching my daughter’s experience at the University of Chicago School of Law, where they focus on career issues from the moment they begin and then frame a diverse range of options that grow out of a great legal education.

How do you familiarize yourself with trends within the architectural profession/academia, and adapt these observations into programming and student policy?

Maintaining contact with alumni from our school provides an excellent window into successful practices and careers – and how students can be most effectively positioned to utilize these opportunities. Our alumni have positions in a wide range of enterprises, including design work and directing in Hollywood, principals in prominent firms with impressive portfolios of work, and successful real estate developers. We view the entry into “the profession” in a far more diversified and entrepreneurial way than many other schools. We want our students to be able to bring their fundamental design skills to an array of relevant settings, always bringing their values, idealism, perspectives, compassion and humility with them from their experience during school.

Do you collaborate with other departments or schools when designing programming?

Tulane has a unique requirement of at least two semesters of public service/service learning within the curriculum (this requirement applies to the entire university, not just architecture). These experiences are always cross-disciplinary in various ways. For example, work with the unique “Mardi Gras Indians” of New Orleans involves architectural design, film production studies, and engagement with cultural anthropology. Work on urban agriculture and youth empowerment projects demands engagement with hydrology, soils, and business planning. These cross-disciplinary experiences are tangible and not just theoretical at our school.

Water has been a major area of focus for design work and community improvement in post-Katrina New Orleans. Several of our projects have received funding from private and public entities and each has included a cross-disciplinary team of hydrologists, engineers, landscape architects and expertise from the community stakeholders themselves.

What is the relationship between the school and local government?

The Tulane City Center is the base of operation for our outreach efforts – with over 80 projects for nonprofits and city agencies completed since 2006. All of these projects are student and faculty efforts working in collaboration with neighborhood organizations, non-profits, and city agencies.we seek to instill a sense of responsibility and ethical conduct in our students through civic engagement We have raised close to $5 million to fund these projects ourselves. The projects, with the extensive pro bono work of students and faculty, have contributed to a strong wellspring of appreciation throughout the community. Most recently, we launched a 7,300 sf community design center in the middle of a challenged yet historically significant and integrated neighborhood named Central City. This center is poised to become the headquarters for the city’s resilience initiative.

New Orleans is a small city, with fewer than 400,000 citizens (and somewhat more than 1 million in the entire economic region). Tulane University is the largest private employer in the city, and, as such, the connections with the community have been strong throughout the history of our institution. Every unit of the university has been involved in the city’s recovery over the past ten years after Hurricane Katrina. Any perception of the university as disengaged from the community has been supplanted with a deep recognition of the positive impact and reciprocal dependence we have with the city and region. The School of Architecture continues to be at the forefront of these efforts.

How would you like the school to have changed in your tenure?

I hope that students and citizens alike will appreciate the unique magic produced by connecting design excellence with social innovation in action. This process builds on a tradition at Tulane School of Architecture that goes back more than 100 years, but the qualities of excellence and engagement have taken on a particularly urgent and highly recognized quality over the last ten years.

How important is it for an architecture dean to be, or have been, a practicing architect?

I am biased, because I practiced architecture or urban design throughout my entire career as a professor, department chair, and associate dean at my prior institution. It has served me very well in understanding the overlapping interests and it certainly reinforces an appreciation for the necessary and productive tension between education and practice. Most of the deans I have admired over the years have practiced, sometimes extensively, sometimes in a more poetic or theoretical mode like John Hejduk. That said, for deans or chairs who are actively practicing, there is an enormous challenge in balancing the competing demands on time, with universities expecting more and more time from deans in areas such as “development” of the fund-raising type.

How do you manage the school’s personality in the eye of the public?

Hurricane Katrina forced a fundamental reconsideration of the role of our anchor institutions in a city whose very existence was thrown in question through the human-caused disaster of the levee failures and flooding of roughly 80% of the city. The perception of the School of Architecture has emerged over the last ten years as engaged, empathetic, creative and relevant to a city that still has a long way to go in its fully inclusive Renaissance. Across the board, Tulane is seen as an influential and positive force in the city’s recovery, with students and faculty playing the lead role in creating a spirit of relevance through engagement.

How do you teach students a code of ethics in architecture?

The best way to emphasize ethics is to explore both the theoretical basis of professional ethics and to instill a sense of responsibility about the individual’s role in developing his or her own personal value system about the role of design as a potential tool for ameliorating injustice or inequity in society. Diversity matters in this regard. Architecture is a social art, and our educational model and our position in society are both enriched and ennobled by increased diversity in schools, the profession and leadership positions. As an ethical imperative, it is important to the health and cultural sustainability of our society and crucial to each person’s role in creating a better and more just future.

For more specific examples, we launched a new graduate program four years ago in sustainable real estate development that extends the reach of our ethical position as a school of architecture. Architecture is a social art and our educational model and our position in society are both enriched and ennobled by increased diversity in schools In addition, we recently launched a university-wide minor in Social Innovation and Social Entrepreneurship that engages students in design thinking and creating innovative solutions to problems in their communities. This is the fastest growing minor on our campus with well over 100 students declared and many more involved with our courses. SISE has expanded through a generous $15 million gift from a donor, and through her support we have launched the Phyllis Taylor Center for Social Innovation and Design Thinking, entering its second year this fall.

We have been working to be adaptable to changing dynamics in society, relevant, diverse in our approaches, collaborative, impactful and ethically focused in our planning and action.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

6 Comments

great school in a great city. enjoy it while it is still above water.

I got great feedbacks for this school. I wish I would an architect just to study there

It is a great city...so why doesn't any of the student work reflect what makes it great?

Thayer, what do you mean?

While I'm not the biggest fan of "community-driven" design as and end unto itself, I do think the student work reflects a contemporary attitude which responds to the same climatic, site, and resource conditions that made the vernacular architecture great.

The work is really along the lines of Coleman Coker and Sam Mockbee's rural studio (in fact, I would place Byron Mouton and Nick Marshall as peers with those two). That is, it is a low-key and affordable take on contemporary design with a focus on community engagement, transit, and climatic and site conditions. Modern regionalism. I'm not sure what your quote is referring to, but maybe you could clarify?

master of preservation studies, master of sustainable real estate, tulane city center and urbanbuild. i'd say they are very focused on the city and what makes it great.

they do focus on those things that make the city great - both from history and from now. the work reflects both, depending on the student and the faculty and the goals of a given project.

what new orleans and tulane get right is a similar dialogue between modernity and history that you find in european cities but so seldom in american ones.

i'm glad that schwartz seems to be settling in at tulane. the school needed a vision and some continuity. (scott bernhard was great, but was only empowered to go so far as interim dean.) too many deans use schools like tulane as a stepping stone. it needs and deserves his commitment.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.