Buoyantly imaginative yet grounded by a commitment to sociopolitical realism, the work of the Greek-born architect Andreas Angelidakis defies categorization. In fact, while he was trained as an architect at SCI-Arc, Angelidakis' work is perhaps better known in contemporary art circles than among architects. After all, Angelidakis exhibits in museums (and online) more than he builds. Yet his work, which takes the form of renderings, videos, sculptures, dioramas and installations, is visibly marked by an architectural sensibility. With near-manic intensity, Angelidakis’ work operates fluidly on the uneven terrain of the contemporary moment, invoking ecological disaster, digital and post-digital networks, economic crises, celebrity culture – often all at once. At the same time, specters of history – both imagined and real – never escape his expansive purview.

I first encountered the work of Angelidakis at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens. In the entrance lobby, he had erected scaffolding over the stairs, although I wasn’t aware it was part of the exhibition until I was leaving. With a combination of subtle and grand gestures, he had completely transformed the architecture experience of the museum’s subterranean galleries while simultaneously presenting a retrospective. Strange models stood on pedestals in front of large renderings, collages, and projected videos. A hand holding a modernist glazed box jutted out of a mountain. A machine-like building climbed over the neighborhoods of Athens. In one room, tapestries covered the walls and floors, which were littered with re-purposed antique furniture. The adjacent hallway was crowded with inflated faux-concrete slabs and capped pyramids, some of which were embellished with digitally-printed graffiti.

I reached out to Angelidakis to discuss some of these works and others, as well as his relationships with the internet, ecological awareness, and, of course, architecture.

From what I’ve gathered from your biography, you were trained as an architect at SCI-Arc and identify as one. Yet your work tends to be found within contemporary art contexts. How do you situate yourself in relation to these two fields, which remain divided for the most part (at least in the popular imagination)?

While studying at SCI-Arc in the late 80s and early 90's I got introduced to contemporary art by my friend Jim Isermann. LA was a vibrant scene that included Mike Kelley, Cathy Opie, Jim Shaw, Richard Hawkins, Dennis Cooper and many more – so while being trained as an architect, I got this extra education from Jim and his friends. I never really distinguished between art and architecture though I did understand that artists were quicker, and much less prone to insist on their “taste” as a guiding force for everything they did. Architects have this thing were they use all their powers to get the “realized” object to be as close to what they imagined, and I realized I was more interested in the process of ‘lets put these things together and see what comes out.’ So I guess I decided that the tools of architecture education were really super useful, but less so what is generally expected of architects. And SCI-Arc was a great place to learn this.

The internet teaches us that you don't really need material things so much, you just need bandwidth and attention vitamins, a laptop and a cave to chill out in.

Your work, in particular projects like Monument to an Oncoming Disaster for the Athens Marina, evidences an intimate awareness of ecological issues and a broader sense of imminent catastrophe. I’m wondering if there’s a relation between your specific mode of working and ecological awareness. At the same time, your work feels very at home on the internet, and seems concerned with both the aesthetics and conceptual ramifications of networked culture. In Domesticated Mountain, you describe the internet as “an expanded notion of suburbia,” that the “suburban home is the accumulation of all the things we do online.” How has the internet transformed the experience and ontology of dwelling and, by extension, architecture?

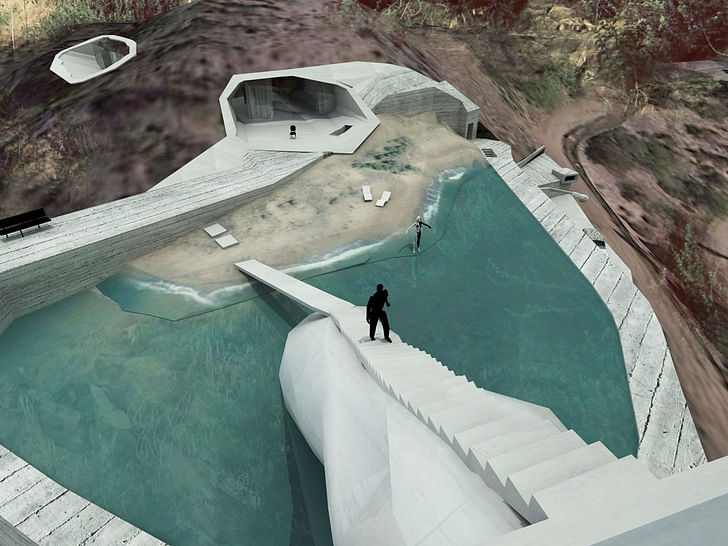

I guess I approach ecological disaster from a romantic point of view, a sort of “fin de siècle” obsession, and let’s all go live on a beach without buildings. Monument to an Oncoming Disaster was a competition by collector Dakis Joannou, for an entrance structure to the marina where he keeps his Jeff Koons-painted super-yacht Guilty. So I wondered what could be further from that slick colorful boat, and I came up with this disaster scenario structure made from stuff you would find around the marina anyway. Of course whenever you build something “ecological” or you buy a new hybrid car or whatever, you're immediately not ecological anymore because its always better to just use the old stuff. And that fits really well for me since I was always fixated on ruins and archaeology. So all my ecological projects are somehow prehistoric-tech, like Dolmen and Menir. The internet teaches us that you don't really need material things so much, you just need bandwidth and attention vitamins, a laptop and a cave to chill out in. In any case architecture does not really cater to need anymore, the modernists figured out how to take care of all that. For the last 40 years its been more about “want” and what we want at the time of internet changes much faster than a house.

Putting things together is faster, and there's been so many things designed already, that dealing with how and why to put them together is more fun.

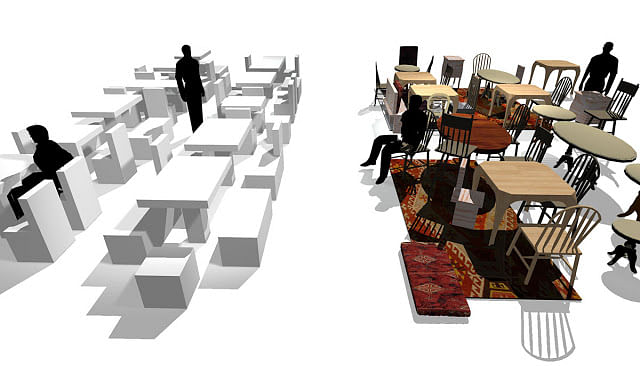

Whether digitally, physically, or both, your work often makes use of collage techniques, in copying and pasting. For example, with Feeder, you construct strange aggregates of apparently divergent aesthetics: lacquered modular furniture is bolted to found antiques. Can you talk about your interest in unusual combinations and the way you move from the internet to the physical (and back).

Obviously the internet is all about copy-paste, so to be designing stuff feels really ancient and wrong. Putting things together is faster, and there's been so many things designed already, that dealing with how and why to put them together is more fun. Feeder and subsequently CrashPad are very specifically about the history, the politics and economy of Greece since 1821; the country as a collage between a nostalgia of an ideal antiquity and a Folklore reality coming from the Ottoman empire. Ideal antiquity is organized, calculated thought-out – architecture and Folklore reality is making something with stuff you find lying around, like used furniture from a flea market. It's a collage between the monumental and the particular, and somehow I think that relates to the hieranarchy of the internet. In the late 90's when I started building stuff in online communities like Active Worlds, it happened that I would post queries on how to build, and I would get answers from teenage kids, and that really helped demolish any architect-type ego I might still have had. And copy-paste was the only way to build anything online, so it just became the default mode.

We live in a time where our ideas and feelings towards objects are often more important than the object itself.

Looking at your work, it seems inadequate to discuss either its ecological or technological aspects in isolation. In projects like Hand House, there’s a frenetic sense of collapsing multiple lines of thought: disaster, celebrity, the semiotics of architecture, issues of privacy transparency… the list could go on. Your capacity to hold divergent, even contradictory thoughts together and translate them formally is really impressive. What is your process like? How do you approach on object of study?

Hand House was meant as a portrait of LA through a Twitter feed, so it was natural to collage all these conflicting ideas, which LA is about anyway. It was a prehistoric Kardashian Mulholland mudslide actress-waitress glass house, pushing forward the notion that Los Angeles is the ultimate internet suburbia where all these things can co-exist. I guess the only thing I really “design” is narratives for objects I find and put together, and this process does not need to be defined as completed by a realized object. You can keep designing even after the object is there, because it’s a mental process. And we live in a time where our ideas and feelings towards objects are often more important than the object itself.

In my head I'm always living in the past, always redesigning the story, even if I'm imagining something that doesn't exist.

Jumping off the last question, you also have worked in more pragmatic modes, for example with your work in Väsby, Sweden. With that project, which involved proposing development methods, your process was very research-oriented and sought to involve the local citizenry as much as possible. Can you talk about this project and your views about how urbanists should approach working with public space?

I'm glad you ask about the Väsby project, because it’s one of my favorites, even though it never concluded. It started off by Jan Aman and Mia Lundstrom asking me to design a pavilion for workshops, and me finally realizing that building a structure was not the way I wanted to use my architecture skills. And I had been re-reading Margaret Crawford’s text on Shopping Malls, so I proposed to have all the workshops held in the town’s center square, ancient Greek style, which of course was the local shopping mall atrium. That process produced incredible interactions between developers, city officials and citizens, which was the goal anyway. And seeing a developer explaining what they were planning to build to a senior citizen was priceless, especially when the old lady suggested that they build a playground next to the old people's home so that their grandchildren visit more often.

The project then clarified into a method of using cutting edge architecture and urbanism research to attract media, which would in turn attract investment. When the plug was pulled on the project we had already put together a book of proposals by people like Keller Easterling, Jorge Otero-Pailos, Andrés Jaque, Kazys Varnelis and many more. Sadly the plug on the book was pulled too – that can happen when you mix radical thinking with politics and business – but bringing those worlds together was the most exciting part of the project anyway. And I think it resulted in a fantastic blueprint on how to process development.

I'm all for a radical greekification of Europe, let's just burn it all down and see what new kind of continent we can come up with.

I’m fascinated by your investigations of historical and contemporary Athens, how you consider the latter always in relation to the former. In a past interview you described Athens as “the one city in Europe where the financial crisis was physically visible.” What are your thoughts on the current situation, the apparent stand-off between Syriza and the EU (and related international bodies)?

In my head I'm always living in the past, always redesigning the story, even if I'm imagining something that doesn't exist. Athens is the perfect city for this, because it’s part ancient ruin and part contemporary ruin. Again, Feeder and CrashPad are projects that dealt with these conflicting identities of Greece, the Europeanized, educated Neoclassical return to antiquity and the folklore foreclosures of beach and spanakopita in contemporary Athens. It all started with a book I bumped into at an airport, A Concise History of Modern Greece by Richard Clogg, which made clear that the position of Greece in Europe was questioned from the very beginning of its liberation from the Ottoman Empire, and it is still very much in dispute. I voted for Syriza, but mostly for the pro-LGBT stance, because they promised to finally pass a law for civil unions. They still haven't, so I'm hoping it was not only talk. I'm also a fan of Varoufakis, and I think his aggressive trolling of the European finance ministers is just what was in order, because the situation in Greece is ridiculous. Basic things like paying your mandatory state health insurance have become luxury options, and the basic provisions that the rest of Europe take for granted are science fiction here, like for example having heating in your home at winter. Varoufakis was one of the few people that really clarified that the Greek crisis was really just a bank crisis, and the rescue packages went to the banks and not to the people. Sadly this creates a reputation for Greeks as the pariahs of Europe, but maybe when you lost everything else, all you're left with is swag, so I'm all for a radical greekification of Europe, let's just burn it all down and see what new kind of continent we can come up with.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

1 Comment

I am so glad to see Andreas's work on Archinect!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.