Painters paint, sculptors sculpt, and writers write, yet architects do not architect – they draw, model, and write. Architecture is one of the few creative fields that does not allow the artist to work in the medium where the final work will be produced. Yet Oyler Wu Collaborative makes productive use of that cognitive jump.

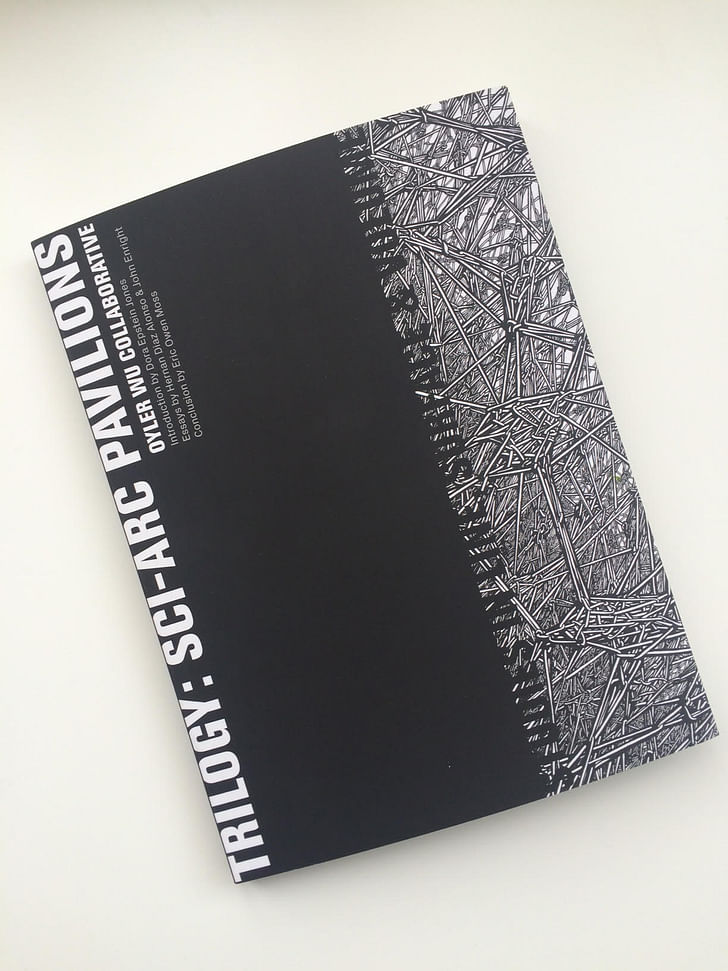

Sketches, models and other objects become artifacts of the architectural process, of thinking and speculation. Yet drawing has been, and continues to be, architecture’s most valued avenue of loosened discovery, one that invites emotion and sensation, unimpeded by the needs of ADA, circulation or gravity. Drawings and models have come to be understood as acts of architecture in and of themselves, not dependent on building to solidify their meanings. Exploiting this freedom is where Oyler Wu Collaborative (OWC) and their work exist, in a constant back and forth between final and process, between polished and messy. Through their newly released book, “Trilogy: SCI-Arc Pavilions”, Oyler Wu aims to position itself directly within these dichotomies.

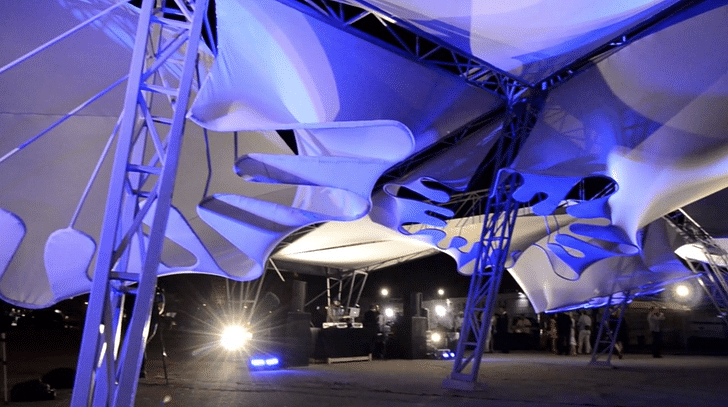

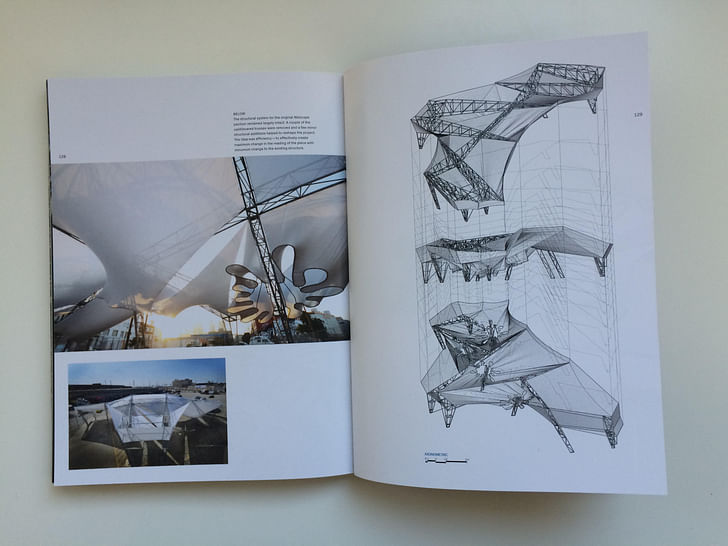

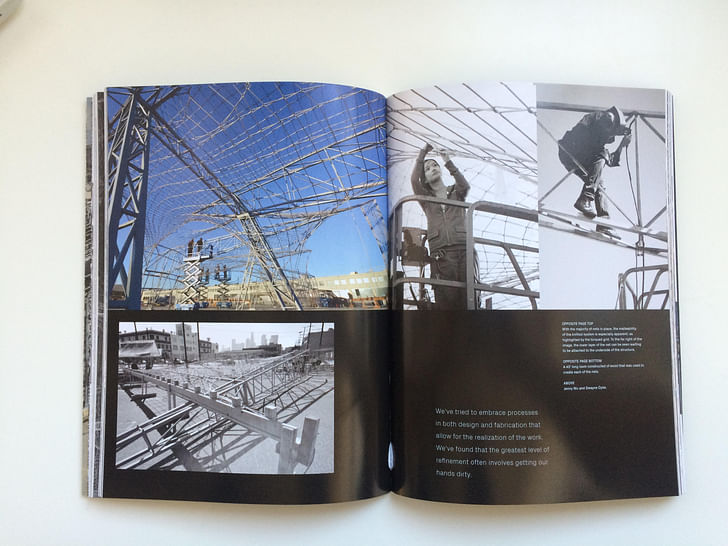

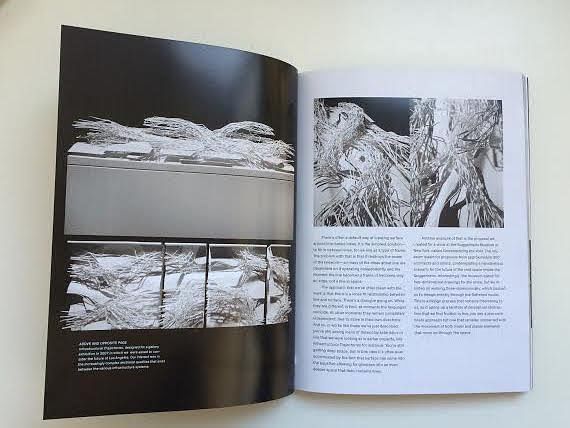

Zaha Hadid, Bernard Tschumi, Frank Gehry and countless other architects have exploited the pavilion’s qualities that allow for a wide variety of formal and material explorations while simultaneously embracing their temporal existence and looseness in building code requirements. Due to these factors, the timeframe from conception to finalized structure is exponentially shortened, allowing for ideas to get tested and implemented and improved with ease. “Trilogy: SCI-Arc Pavilions” presents three OWC pavilions over three years: Netscape (2011), Centerstage (2012) and Stormcloud (2013). Each of these projects were constructed in the parking lot of The Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc) in downtown Los Angeles, as spaces designated for school events, and signified an evolution of OWC’s Drawings and models have come to be understood as acts of architecture in and of themselvesresearch over that time period. Each pavilion was built with similar materials, some with the same structural members, yet each one distinctly more polished than before; each presented with such comfort as if to prove they can draw as effortlessly with steel as with graphite. Each iteration within the project is simultaneously complete on its own, while also advancing its preceding version.

The architectural practice is one full of reduction, simplification and erasing, yet all levels of creation within the Oyler Wu, their book and the exhibition exist on equal levels of refinement and purity. Scale and detail emerge as important themes, turning the pages from drawing, to model, to pavilion with ease. Routinely in architectural work, there is a build up from abstract, simplified sketches to finalized production, yet when immeasurable manifestations of detail are added, that gradient fades. Erasing all reference of stability, stitching, thread, pencils, jackhammers, cars, and tables, these are the elements you find yourself looking for, to obtain some level of clarity. As in their most recent SCI-Arc pavilion, STORMCLOUD, the work continuously delays its simplification. Their models, drawings, sketches and final production all seem to plumb a deeper well of rationalized complexity.

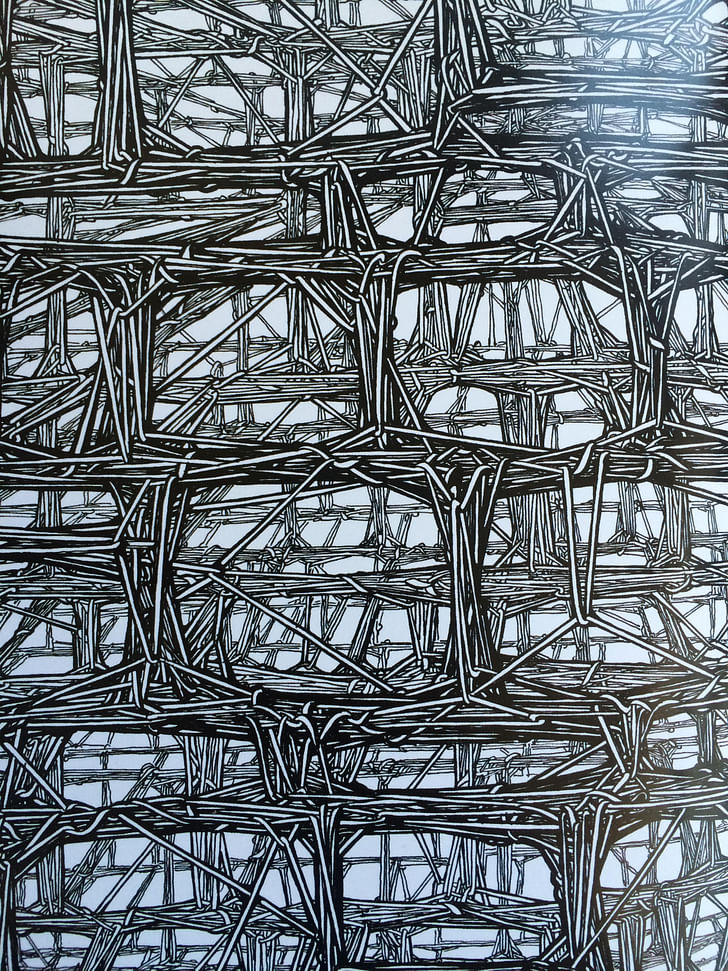

In a time where hand drawing may seem vintage and analog, the digital seems to have become the quid pro quo of architectural discovery. The release of the new OWC book gave the firm a chance to also exhibit some of Dwayne Oyler’s personal hand drawings, in an event held at the SCI-Arc library on January 16, pitting the complexity of the firm’s digital production right against the collection of ink drawings.

As stated by Oyler Wu in their book, concerning the role of drawings:

“You instantly recognize that every element is doing work, but it’s difficult to quickly understand what work it’s doing. We’ve always though that’s what made the work, or any drawing for that matter, interesting is its ability to prolong the duration that you experience it.”

Dwayne Oyler, who worked for a period with Lebbeus Woods, has a deeply instilled drawing pedigree that continues to prosper in his work today. The drawings are produced in ink on various sizes of Bristol paper. His drawings may not strive to track movement, embrace structure and produce program, but they succeed at allowing for a space of activity to occur, every element is doing work, but it’s difficult to quickly understand what work it’s doing.and allow thinking and technique to be exploited as intentional acts. It is a visualized production of the act of thinking, one done with the tools at the architect’s disposal. At first glance, the drawings present themselves as doodles, yet doodles imply roughness and there is no roughness to be found. To the contrary, they are all a series of fully realized and self-sufficient works.

They neither relate nor distance themselves from the practice of the firm as a whole. Just as the Pavilions manage to simultaneously relate to one another while also distinguishing themselves from any another, the drawings do the same. They do not serve their conventional purpose of, say, section and plan, but something else, something behind the projects. These drawings are made at moments when no project is at hand, but when time is alone, when most of us would sit and watch a show, Dwayne Oyler sits for 18 hour stretches to ink a drawing. The drawings on the walls are a collection of the last three years of outlier moments in Dwayne Oyler’s life. They are meant to convey a process of thought, buying time to think while also moving forward, or as a memory of a moment in his life, a timeline.

Drawing is the honesty of the art. There is no possibility of cheating. It is either good or bad." – Salvador DaliEach study was presented alone, framed and hung as one would experience in a museum. Each has a name, a series, a date and a year. Where architecture usually finds itself on a table or a studio wall, these drawings are framed, centered and hung with nails, creating an atmosphere that compels the viewer to experience it from a new intersection of art and architecture. More pleasure arrives from the discovery and tension within these dichotomies than from any concrete grounding in either realm. Writing these drawings off as inspiration, or sketch is a common default tendency. Delaying that tendency grants these drawings space to exist on their own and allow the occasional architectural interpretation.

While ideas still have a need to be visualized through forms and media, these are not passive tools that should be considered defaults in the architectural process. This is where OWC stands among the few. OWC finds themselves in an area where the architect’s tools have become choices and completed works in themselves. A model is not a submissive building, and a building is not a finalized version of a model; each opportunity is engaged with the same duality of grit and refinement.

Painters may paint, sculptors may sculpt, and writers may write, but Oyler Wu Collaborative is finding their own act.

Anthony Morey is a Los Angeles based designer, curator, educator, and lecturer of experimental methods of art, design and architectural biases. Morey concentrates in the formulation and fostering of new modes of disciplinary engagement, public dissemination, and cultural cultivation. Morey is the ...

3 Comments

From the photos of exhibited drawings it showed be called Variations of Konrad Wachsmann.

I would love to hear more about the influence.

One just can't right enough about the critical importance of pavilion architecture...

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.