Felix Melia and Josh Bitelli are artists who live and work in London. We met last year and have remained in contact through email since then, exchanging periodic updates and continuing our fragmentary, rambling conversations over shared interests (and confusions) regarding the contemporary urban experience. Threads of continuity arise between individual emails with each of them, unsurprising since the two are old friends, share a new studio space, and often collaborate. Our conversations are inescapably informed by the digital media that allows them but at the same time bears traces of a perhaps nostalgic notion of letter exchanges. Both Melia and Bitelli investigate the city through the (often unnoticed) infrastructure and industrial processes that support it, while also grappling with the shifts in phenomenological experience produced by the internet – all of which is often tinged with an undeniable romanticism.

A few weeks ago, through the choppy slipstream of a bad Skype connection, they showed me the view from a large window in their studio that seemed to fill the space with light. Bitelli disappeared from view before returning to show me the frame for a green screen they had made for one of Melia’s new works. We discussed, among other things, the increasing unaffordability of London and Los Angeles; North African cityscapes (they recently returned from Morocco where they co-created a video for Marrakech Biennial 5, while I spent time in Tunis several years ago); their ideas about contemporary architecture practices; the architecture of road trips as cinematic (and the soundtracks we choose for them).

In particular, I asked them about the ways they viewed their work as relating to architecture. Bitelli creates furniture and other useful objects that are not only beautiful but loaded with conceptual meaning garnered from their production, which is derived from his thoughtful interventions into existing fields of industry. For example, after becoming acquainted with local roadworkers, Bitelli collaborated with them to fashion tables and chairs using asphalt and road marking paint (the processes involved in such works are documented on videos available on his website). Melia makes videos, websites, and studio works that often interrogate the manner in which one experiences built morphologies, in particular examining the distances produced by expectation as well as processes of mediatization.

As our conversation was periodically interrupted by glitches, we noted the improbable passage our images were making through cables under the Atlantic and across at least one continent. There were moments that I couldn’t understand a word of what they were saying and likewise they almost certainly had to fill in the blanks with my questions. But the same could be said of our email exchanges, in which a forceful combination of nonsense is often used to convey something more important than an articulate and succinct sentence could ever hope to (or at least I would like to think so).

Later, I sent them both questions via email, intending to retrace key aspects of our conversation and convert it into an interview.

Last time we talked, you were describing the most recent film you collaborated on in Morocco for the Biennial. The film – Place of Dead Roads – consisted of a loose narrative that followed a motorcycle bearing a transparent flag along an unfinished road, which was actually intended to serve as a racetrack. Can you describe the film? How did the unfinished road encapsulate certain experiences of infrastructure and architecture to you?

Josh Bitelli: We filmed a C90 motorcycle driving down paths cut into the dirt between concrete skeletons and empty billboards: both became screens. There was this expansive road, built to be Africa’s first F1 racetrack that ran from the old town into the mountains. They never quite managed to lay the tarmac flat enough for competition regulations, making for a surreally over-specified commute. Just about the only image that remains on the many otherwise liberated steel-frames is a portrait of the king hoisted above the pit stop that wasn’t to be.

It was important that the images we produced were symptoms of this hierarchical development and picked up on the realities of how people build signs of movement and living in the areas surrounding disconnected architecture on privately owned land. There were a number of key signs in this portrayed heterotopia: the C90 itself had quite a harrowing story around it. [It was a cheap reproduction] of Honda’s best selling Cub 90 [and] kept its status to personal mobility, but the overpowered, crappy bike with underpowered brakes has a hospital ward named after it.

Felix Melia: I was more interested in the latticework of roads that surrounded those buildings, which the video leads through and around. Looking out at the expanse, over which our flag bearers moved, from a distance meant this irregular grid was hidden. They didn’t make up part of the visible landscape until they came to the fore. It was hard to date those surfaces by looking at them – swept with dust and littered with potholes as they were – but they provided a complete labyrinth infrastructure, enabling people to navigate those architectural complexes that lay dormant and unfinished. It’s comparable to that odd, backwards timeline in which the landscaping around a development is completed before the buildings themselves, and the foliage gets covered in dust from the construction.

Those roads were not unlike the buildings they were built to service: skeletal and filled with potential.

Those roads allow passage into and through that space, but in a practical sense they lead nowhere. In a way those roads were not unlike the buildings they were built to service: skeletal and filled with potential. In fact the roads conveyed a freedom of movement and agency that the architecture didn’t. They were indeed in use, and it was brilliant to watch people speed across this arid place without being able to assume a destination. It was as if that hinterland had rejected the closed circuit that someone was attempting to impose upon it.

We also talked last time a bit about the use of the green screen in [Melia’s] work, which opened into a broader discussion on the relation of cinema to place. How does the camera operate in an urban environment, transform it, etc.?

FM: My reasons for using green screen are relatively simple, but they’re a good basis for me to answer the second part of your question. The green screen forges a permanent link between the physical space in which images are made and the illusionary or fictional events eventually realized on screen. The green screen must be installed physically within space, but the superimposition of the secondary image onto the primary image occurs later – in post-production – away from the spatial and architectural facts of the location.

This process is a way of exploring points of perceptual slippage in how we experience space and in turn architecture. The ‘facts’ of a place are embroiled in any number of narrative coils: the aesthetics of capitalism, the infrastructural stack, the socio-political dynamics of an urban area, etc. Places are engendered with meaning; they inherit meaning too. The planning theorist Ole B Jensen talks about the use of narrative and story in designing and transforming places, how in western countries we seek out ‘immaterial’ stimulation to form an identity and make sense of the world. This has lead to the culpable phenomenon of urban branding.

The ‘facts’ of a place are embroiled in any number of narrative coils

Of course a place might also hold some specific significance for the individual that means very little to people in a broader sense. I’m more interested in the vectors and events that transform space before and after architecture.

Cinema certainly has an impact on those faculties that formulate our impressions of the environments we move through and within. The view from a train or car window is another framework that provides a key into this point of slippage, between what is experienced physically and what is perceived based on those contaminated qualities we assign or project. The view through the window of a vehicle is cinematic in that it is literally framed, and the image contained within that frame, the space beyond that frame, is moving whilst the passenger remains still […]

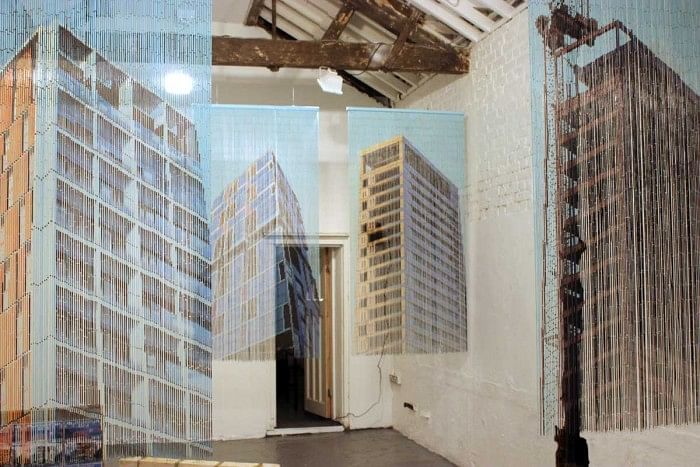

The function of most architecture means that almost all of our movements are choreographed to some extent. My most recent work, “Lamassu Flats”, explores some of the narrative appendages and the protocols that create the impressions that uphold these choreographed actions. I often return to the image of an arch as an architectural representation of the transformative, threshold event, and as an encapsulation of potential energy. Potential energy for me is paramount. This is perhaps where the relationship between cinema and architecture becomes strained but the camera remains wholly relevant. I try to imagine buildings as events embedded within a sphere as opposed to in sequence. I worry less and less about the notions of ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’ or physicality and ethereality in regards to my experiences of architecture because they are too binary. Instead I imagine each object-based event as creating a perceptual threshold, one that is crossed almost immediately and leads immediately to another. I guess it’s a way of experiencing space through a process of narrative and mythological assimilation, moment to moment; it’s like a perpetual road movie!

I try to imagine buildings as events embedded within a sphere as opposed to in sequence.

I’m very aware that this process, to some extent, negates the experience of architecture on a practical level! It may sound like I’m championing the society of the spectacle, and that I’ve lost all sense of architecture as the designation of a set of conditions based on requirements. This is not the case. The sense of physical displacement I describe is a very visceral one; it brings the body, the vessel, into sharp alignment [...] It’s a trial and error exercise in interrelations, and ultimately a way – at least for me – of addressing the practical, social issues surrounding architecture and cities as we experience them.

JB: I like to think of the convergence of imagery from and into the cinematic and the urban as a layering of inseparable elements that – for now – can be bracketed into networked space; things by the internet; things produced by advertising, [things produced by] local government and legislation, communities and family life. Economic growth and architecture from and for the demands of the internet show networked space and physical space as a layering of conditions that, like cinema and place, can’t be disentangled. And the mutual reliance and effects of socially constructed space and the cinematic is visible in something as physical as camera angle.

We realise how affected we are by cinematic mobility when the radical expansion of scale hinders our daily movements.

Cedric Price made a series of walks where people were asked to carry car windscreens – one of the frames we constantly see the world through. Car windscreens make road movies everywhere but when carried, they recalibrate the weight of glass itself, intimacy, vulnerability, speed and detail. I can imagine this unusual commute making me feel drunk. So this type of controlled slippage is really a constructed way of imagining how vantage point or technological and infrastructural progress alters how we perceive and then reconstruct cities. Another favourite articulation of this phenomena is Noam Toran’s If we never meet again, where two spies in long coats meet each other. Noam shot this most reproduced sequence once from a tripod framing their faces against the horizon and once from the air where their hats presented them as pins on a map. With airborne image making came a framed section of vastness that was conquerable, traversable and ultimately inviting. The normalisation of the-view-from-above in photography, cinematic imagery and architectural visualisation brought to question the capacity of the cinema and the capacity of our own physical abilities within built space. In these terms, the disconnect attributed to the lens is not exclusively the physicality of the lens with its historical and representational appendages, but in how cinematic projections have woven their way into the very fabric of constructed space. We realise how affected we are by cinematic mobility when the radical expansion of scale hinders our daily movements.

When you showed me your studio, you told me that it’s in what used to be a blighted area. All architecture inhabits already-occupied space. How do we deal with this? What ghosts haunt the places you study in your work, specifically?

FM: In London the most visible zones of construction are spawned by top-down, speculative developments in which a clear hierarchy is established between developer and user. The question of whether a building is in fact what’s required tends not to come up as far as I can tell. There is little or no contextualisation surrounding new buildings, just the implied narrative of fulfilling one’s aspirations via the gleaming render plastered across construction site hoardings.

There’s a kind of “all-roads-lead-to-Rome” imperialism within Western culture, a prescriptive homogeny that leads to prescriptive architecture. [Architecture is] not being designed in a way that adapts to people – who, I feel, are thought of less as citizens and more as ideal consumers. Work and leisure, love and labour are experienced within the same slipstream; they are synchronised and subjugated. The problem is not that architecture inhabits previously occupied space; but that it is sanctioned through a preoccupation with a framework that caters for all emotional and functional states simultaneously.

Work and leisure, love and labour are experienced within the same slipstream

The other issue is that the developments to which I’m referring often act as shells for speculative investment. They are built into essential obsolescence. As domestic spaces they act as sedatives. They begin life as ghost towns and continue to stand as such! They occupy space but remain unoccupied, sold in bulk to investors who sell in bulk in turn.

This kind of architecture is Totemic, but internally void. I guess what I’m saying is that the city is filled with brand new ghosts! As such, my own negotiations with architecture always start from a place that is very close to the ground. What of the gaps between those buildings? The empty plots of land that do still exist? The small gestures made by developers towards social inclusion and interaction?

Looking at the skeleton of a building, a grid structure superimposed against the sky, we see an alternating pattern of obstacles and portals. There lies the spectre of potential: a translucent image that could be made solid and used as a guide in replacing this discrepant architectural hierarchy. It’s a diagram that encapsulates forms of movement.

The city is filled with brand new ghosts!

I spent three months living in Chong Qing, a city in China. The rate of architectural turnover, and the nature of speculative development, has formed a cityscape that is in keeping with illusionary, abstract notions of a metropolis. The illusion was compounded by speculation as to whether Chong Qing’s famous fog had in fact become a thick smog, more particle than precipitation. But on the ground it was not uncommon to find beautiful moments of harmony between sanctioned and informal architectural events. Cement had been poured down hillsides to form pathways, houses had been erected at the edges of an unfinished overpass. Mustard greens and lettuce grew between the sleepers and rails of train tracks besides which small brick houses had been built. Many of Chong Qing’s citizens move from rural areas into the city, and despite severe economic circumstances the communal spirit was very strong. Social interactions occurred outside in the street where there was more space. Stalls that sold breakfast in the morning were packed up to make way for badminton! It seemed as though the architectural turnover that causes huge problems in affordability and social equality was being mirrored, but that a far more mutually beneficial model, based on cohesion, had been developed in these enclaves.

JB: I attempt to re-imagine these lingering ghosts as loose amalgams of data that simultaneously expand and contract. The places that I work with – and in – are usually quite normal. They are symptomatic or referential of many others. I project these lived worlds and the systems of production that operate within them as a realm that does not and potentially could not exist. At the moment I’m making preliminary notes for a set of walks I’m about to do with horticulturist Tim Rees, a recorded walk that collects snippets of video and sound – not so much as an analytical survey, but as a single layer of information that is constantly in process within this world of overlapping channels.

Land could be understood as the very thing that both connects and separates us all

We plan on walking around the remaining parts of London’s last (and soon to be demolished) post-war, prefabricated housing estate, the Excalibur Estate. It’s the container of a harsh history of brutality and conquest. It was built with German and Italian prisoner-of-war labour, and the roads are named after Arthurian characters. We will talk about plants that were imported to Britain, plant pathology, epiphytes and naturalisation – how well a certain species adapts to the host climate. Social rearrangements seem to happen in waves and for reasons that are more or less severe, this specific relocation of people demanded labour as a means of reparation payment. The produced societal effects aside from new homes included humanitarian campaigns and discrimination, neither of which are absent in the housing estate’s prospective redevelopment.

Where one building overturns another we are faced with a type of archaeology that encompasses not only the numerous other buildings that were never put into production but also the causalities of how these building came about, or were vetoed as the case may be. London’s political climate plays an enormous role in this respect, when a building is not respective of its surroundings – [as is] so often the case – we see frictions as a result of this lack of understanding. The ghost of this kind of competitiveness survives today, and land seems to be understood in terms not dissimilar to that of a car park, when it could be understood as the very thing that both connects and separates us all.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

1 Comment

dig it! and this "a set of walks I’m about to do with horticulturist Tim Rees, a recorded walk that collects snippets of video and sound", and imported plants / imported labor sounds intriguing...

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.