What's working as an architect actually like? Even for students on track to become one, the answer isn't always clear or forthcoming, and for those outside the industry, common ideas about architecture rarely reflect its reality. In this series of articles, "The Life of a New Architect", three architects (two designers and one licensed architect) discuss their transition from student to professional, their changed perceptions of the career and the challenges and joys of their current work.

Listen to enough architects sound off about their profession and opinions will oscillate between zeal and disillusionment, fulfillment and regret. While the recent economic climate has likely helped divide sentiments, what may be just as polarizing is the reality of the work – the tangle of business savvy, management skill and financial risk taking that make up so much of the job yet fall outside popular ideas about the career as well as the curriculum of architecture school. For students, an architecture degree provides little portent of the careers ahead of them; it is no guarantee that the appeal that inspired them to pursue the occupation will exist in their day-to-day work as a professional.

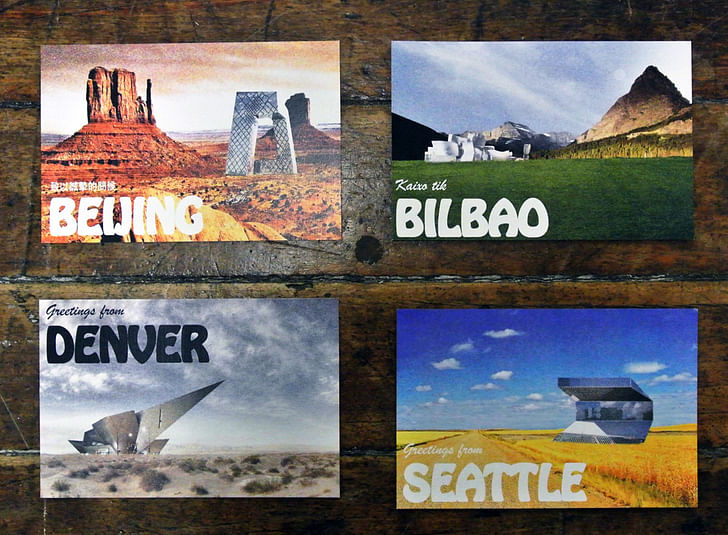

The divide between school and career presents one of many challenges for anyone trying to assess their proclivity for the profession, and the diversity of architecture firms only compounds this uncertainty. Firms vary widely in size, style and culture, from large corporate enterprises to two-person offices, and they design everything from skyscrapers to art installations.

So is there a way to address some of these unknowns short of blithely jumping into the career? Perhaps the best way is to just ask.

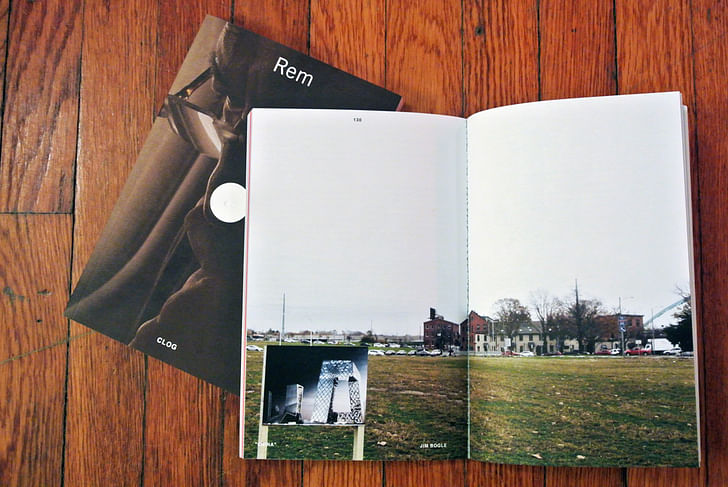

Meet Jim Bogle

Jim Bogle, 24, is a recent graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design's masters of architecture program, and when we met, he was working at Studio Luz, a small firm based out of Boston's Sea Port District. He has since moved on to a new firm, but in our original conversation and a following correspondence, he spoke about his experience at Studio Luz, Though design condenses in a firm, making up a fraction of the overall work, new challenges evoke lessons learned in studio.which he joined fresh out of RISD in June of last year.

Design work takes a "360 once you get into an office," says Jim. In a firm, the autonomy and freedom of design that characterizes school studio projects vanish under the demands of clients, budgets and office hierarchy. However, Jim has not found the divide between schoolwork and office work to be absolute. Though design condenses in a firm, making up a fraction of the overall work, new challenges evoke lessons learned in studio.

At Studio Luz, Jim was engaged in numerous stages of a project's lifecycle, from initial client meetings to final presentations. At the time we met, he was finishing three axonometric renderings of a staircase design for a midblock residential complex. He would present these renderings to the client at an upcoming meeting.

Client meetings typically began and capped off his work at the firm. Jim sat in at initial client meetings where alongside the principals he'd listen to the clients' aims and wishes for the project. He'd then receive a part of the project to design – a staircase for example – which he'd approach first through hand sketches and then develop into a few iterations on the I was able to speak as a project manager of sorts at client meetings months earlier than some of my peers."computer. The iterations would result in three options, ranging from a more traditional design to something more experimental, to be presented to the client as design options.

Though just out of an M.Arch. program, Jim's contribution to projects and his responsibilities at the firm surpassed his own expectations of what starting out in the career would be like. Since he was at times the only employee working under the principals, Jim's level of responsibility came out of the demands of a busy, small firm. As some of his other friends who recently graduated were confided to "CAD monkey" jobs at larger firms, Jim was taking on leadership roles earlier than most designers starting in the career. "The principals, Hansy and Anthony, put a great deal of trust in me, which I appreciate. I was able to speak as a project manager of sorts at client meetings months earlier than some of my peers. Of course there is an increased workload that comes with that privilege, but it was in no way too much."

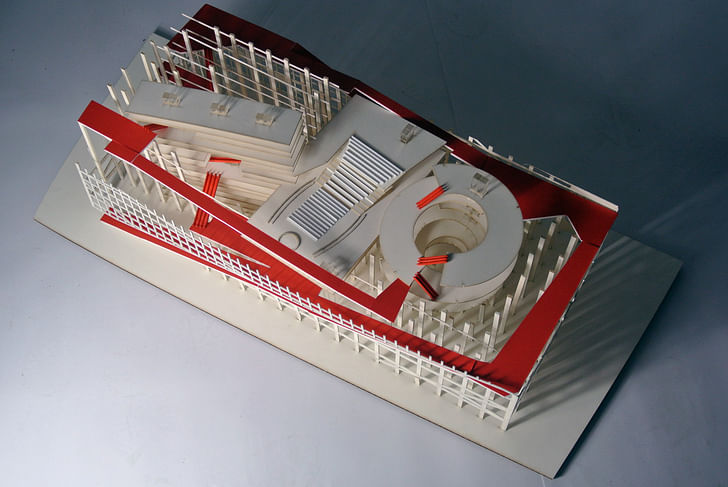

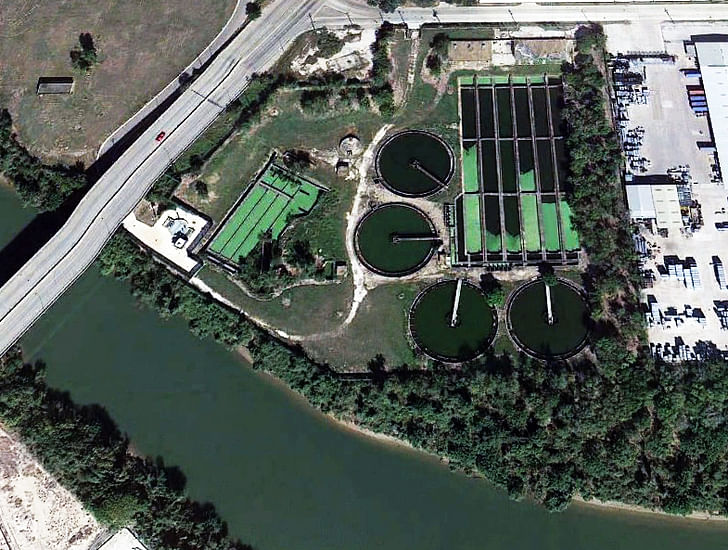

Studio Luz operates out of a renovated warehouse just across the Fort Point channel from downtown Boston, in a first-floor office no larger than a two-bedroom apartment. When I met Jim, he was working at a computer sitting on a slim desk that ran the length of the back wall. Above the desk, a shelf held a haphazard display of models, chronicles of Studio Luz's previous projects and proposals. At Studio Luz Jim was never more than a few feet away from the firm's two principles, Hansy L. Better Barraza and Anthony J. Piermarini, which made for I came to see an architect as a ringleader … organizing and communicating with the menagerie of specialists needed to put a building together."an intimate atmosphere, a drastic change from Jim's experience at an internship with a large Texas firm during his undergrad years. It was during that internship, however, that Jim got his first taste of what the career was like outside of school, and it fundamentally shifted his perception of what it meant to be an architect.

"[In the internship] I came to see an architect as a ringleader, coordinating between engineers and clients." The notion of the architect as purely a designer gave way to the realization that architects spend most their time organizing and communicating with the menagerie of specialists needed to put a building together. "I think for most people [this is] a realization that comes pretty quickly into working." This new conception of an architect only grew while working at Studio Luz as Jim observed Hansy and Anthony coordinate and communicate with clients, engineers and consultants. "I got a very real look at what it takes to run an office and was able to talk to them about it frequently."

The shifted perception of architecture he gained during his internship prepared him for the reality of the career after school. Initially, the realization was a let down: the emphasis on drawing, a long-time passion of his, hooked him on architecture when he took his first architecture class as an undergrad, so to discover so much of the career was communication and management came as a disappointment. For Jim, however, the disappointment was subsidiary. Architecture lost some of its appeal in the realization of what the field was actually like to work in, but he accepted this reality knowing the career was still what he wanted to do.

Looking at the career ahead of him, Jim eventually wants to have his own small firm, which would specialize in small buildings and installations. He'd also like to teach. Until then he takes satisfaction from the work assigned to him. Asked about the best part of the of actually working in architecture, Jim responds, "That's an easy one: meeting a deadline. Meeting a deadline is like taking a bite out of your favorite food after staring at it for 10 hours."

I write, travel and take pictures. My interests include design, identity and natural and urban landscapes.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.