Water has become a central focus for both the Islamic State and its combatants in the current struggle being waged over the large geographic area of northern Iraq and southern Syria. Previously overshadowed by the conflicts in Gaza and Crimea, the rapid emergence and expansion of the Islamic State (IS) has recently become the focus of international media attention, accelerated by the release and dissemination of a video depicting the execution of American journalist Steven Foley, allegedly by the IS.

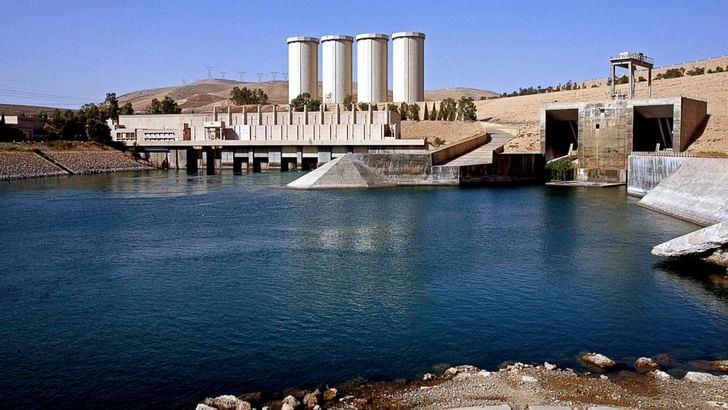

This is an area that has historically been arid, but is also experiencing one of the most severe and prolonged droughts of the last fifty years. Fundamentally, whoever controls the water controls the region. As the IS has rampaged through Iraq, hydro-infrastructure has been one of their main targets. Most significantly, in early August, IS forces took control over the vital Mosul Dam which provides power and irrigation to a large swath of Iraqi land. On August 14, Obama ordered strategic airstrikes specifically to “retake and establish control of this critical infrastructure site.”

The Mosul Dam is the fourth largest dam in the Middle East and a significant character in its own right, regarding recent events and the region’s greater history. For many, the news that the IS had secured the Mosul Dam signaled both their increasing power as well as their strategic intentions. US Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel asserted that, with the IS, “the sophistication of terrorism and ideology married with resources now poses a whole new dynamic and a new paradigm of threats to [Iraq]." Formerly called the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), this group of Sunni jihadists renamed itself after declaring its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi caliph, and thereby announcing its ambitions to claim religious authority over the entirety of the Islamic world.

The IS has been noted for its violent imposition of a strict and particular interpretation of Shari’a Law, exhibited in public executions and genocidal attacks on Yazidis and other ethnic minorities like the Kurds as well as Shia Muslims, the majority group in Iraq that has historically persecuted the Sunni minority. But, as Hagel stated, the extreme violence of their expansion has been accompanied by sophisticated strategies largely unprecedented in jihadist groups. In addition to their focus on water infrastructure, the IS has been noted to target oil fields and experts estimate that the IS currently generates around $3 million a day in selling off oil, making it “the richest terror group in the world.”

The dam could [have] become a weapon itself.

Potentially, the IS hoped to used to Mosul Dam to generate revenue, extorting money in exchange for water and power. But the dam could also become a weapon itself, according to Stuart W. Bowen Jr., the former US special inspector general for Iraq reconstruction. This is not unprecedented: in April of this year, the IS captured the Fallujah barrage and flooded vast areas, forcing thousands to flee in some areas and simultaneously restricting water access to others, adding thirst to their arsenal (http://english.al-akhbar.com/node/19385). Moreover, the Fallujah dam played a vital role in the area’s agricultural irrigation, so sabotaging it will undoubtedly produce future dramatic food shortages. If the IS were to have destroyed the Mosul Dam, a 65-foot wave would have been unleashed across areas of northern Iraq, reaching the city of Mosul and its 1.8 million inhabitants in just two hours.

This is not, however, the first time that the Mosul Dam has become the center of military conflict. A 2003 report documents how after the US invaded Iraq in that same year, American military intelligence feared that Iraqi forces loyal to Saddam Hussein had rigged the dam with explosives. While ultimately untrue, the large Kurdish population in the area could have been targeted victims of militaristic flooding. Actually, it was members of Kurdish militias that had provided security for the dam throughout the early days of the war, in extremely distressed conditions. American inspectors at the site noted that the workers – nearly 500 in number – had been operating the dam since the beginning of the war without pay. More incredible still, the computerized controls had failed and operators had been running the facility manually.

If the dam were to fail, the city of Mosul would be under 65 feet of water and Baghdad would see up to 15 feet.

The selflessness of these workers is particularly commendable because even without sabotage, the Mosul Dam constantly wavers on the edge of failing, due to its lack of structural integrity. The earthen embankment dam was constructed on soft gypsum, a mineral that dissolves when in contact with water. A complicated grouting system stabilizes the precarious facility but requires constant maintenance, which entails constantly filling in cracks as they surface. If, even for a short period, the dam is not maintained, it would collapse and have devastating effects. A 2006 report by the US Army Corp of Engineers stated, "In terms of internal erosion potential of the foundation, Mosul Dam is the most dangerous dam in the world." If the dam were to fail, the city of Mosul would be under 65 feet of water and Baghdad would see up to 15 feet. Half a million people would die.

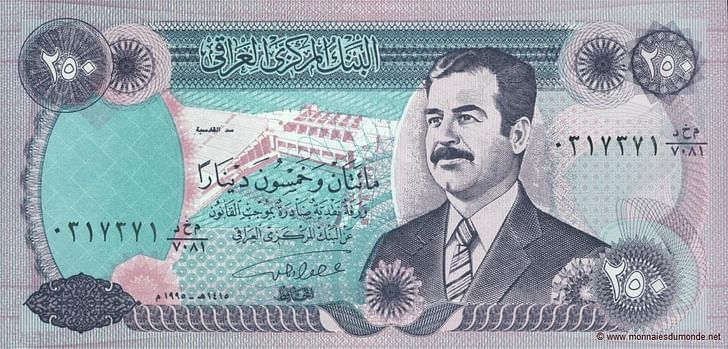

Initially referred to as the “Saddam Dam”, construction on the Mosul Dam began in 1980, at the beginning of the Iran-Iraq war. The project was important to bolster support for Saddam Hussein during the conflict and promoting Ba’athism, an Arab nationalist ideology that combines socialist modernisation efforts with a secular, single-party government. The dam was built by a German-Italian consortium led by Hochtief Aktiengesellschaft, the same company that had engineered the Aswan Dam in Egypt some twenty years earlier, only for it to be similarly used by the then-Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser to promote his own pan-Arab ideology. While Nasser’s construction was intended to promote Arab nationalism in opposition to the monarchies of the time, the political situation in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) changed dramatically by the time Hussein began work on the Mosul Dam. Hussein was threatened most, both politically and ideologically, by the Islamic Republic of Iran, led by the Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini after the 1979 Iranian Revolution. While the Iran-Iraq war was, at the time, significantly dominated by the differences in these competing ideologies, in retrospect it was just as driven by resources as today’s conflict with the IS, with resource infrastructure playing a similar military role. For example, on November 22, 1980, Iranian forces bombed the Dokan Dam in northern Iraq. The region’s fragile system of allocating scarce resources has made water the ghost lurking behind its war-plagued history.

The region’s fragile system of allocating scarce resources has made water the ghost lurking behind its war-plagued history.

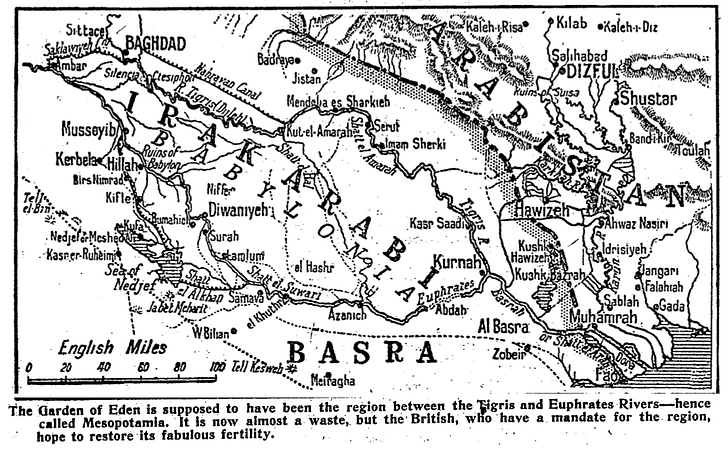

Even before the rise of Hussein’s regime, the area of the Mosul Dam was scouted as a potential site for a dam despite its precarious geography. A New York Times article from 1957, states that a British company had been awarded the contract for initial drilling to test the viability of the site, revealing that the ruling Hashemite Kingdom of the time also eyed hydro-infrastructure as a means to shore up support. Even earlier, a 1919 New York Times article entitled “Remaking the Garden of Eden,” (steeped in the fraught colonialist rhetoric of the time) describes British plans for the then-mandate of Iraq to “restore [the mandate’s] fabulous fertility,” through an extensive series of dams and canals. But even then, the technical and economic infeasibility of this was noted, long before water scarcity surfaced as perhaps the defining issue of the contemporary era.

Michael Stephen, deputy director of the Royal United Services Institute think-tank in Qatar, is quoted in a recent article for The Guardian, stating, “We are seeing a battle for control of water. Water is now the major strategic objective of all groups in Iraq. It’s life or death. If you control water in Iraq you have a grip on Baghdad, and you can cause major problems. Water is essential in this conflict.” While the pivotal role of water is obviously not new for the region, the long-standing drought as well as rising temperatures intensifies its importance. Syrian forces loyal to Bashar al-Assad, the dictatorial ruler of the country before and during its prolonged civil war, have been documented using water, or the lack of it, as a military weapon — just like the IS.

Coupled with a changing climate, the effects of the IS and other attacks on hydro-infrastructure will create an unprecedented humanitarian crisis.

While evidently not new, the militaristic use of water and its infrastructure significantly exacerbates an already pressing problem for the region. Coupled with a changing climate, the effects of the IS and other attacks on hydro-infrastructure will create an unprecedented humanitarian crisis, one that is already becoming visible. Additionally, current and planned water management in the greater region poses a significant threat to Iraq. Both Turkey and Iran already capture large amounts of water for their own agriculture and energy before it enters Iraq. The Kurdistan regional government plans to complete the Bekhme Dam along the border of Iraq and Syria on a major tributary of the Tigris. And by 2018, Iran plans to create a new dam that would divert even more water that normally flows into Iraq. Such water diversions, coupled with the lack of rainfall, will exacerbate drought conditions in region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the key agricultural region of the country. As Akio Kitoh of Japan's Meteorological Research Institute put it in an article for The New Scientist: "The ancient Fertile Crescent will disappear in this century." While riparian rights have long been a contentious issue between nation-states, contemporary ecological crises have the potential to provoke countless wars in the region, with perhaps the current conflicts serving as just the beginning.

In light of this, contemporary water management practices must be critically and urgently re-evaluated. Thayer Scudder, described as “the world’s leading authority on the impact of dams on poor people,” recently asserted that while long-touted as a major boon for developing countries, dams have more negative repercussions than positive. They often require their creators to assume crippling debt for their construction and are, obviously, ecologically destructive. Moreover, Scudder found that the displacement of populations caused by dam construction largely produces poverty and social disintegration. Plus, they require enormous resources to construct but with pay-offs that are normally much below predicted levels. He finds dams “ineffective in resolving urgent energy crises.” And regarding cases like the Mosul Dam, their potential to be used by the militarily is just another detracting factor that must be taken into account before new dams are constructed.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

1 Comment

Very interesting read, thanks for sharing it.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.