45.2 million people are currently displaced by conflict and persecution, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The number accords with the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees articulation of a refugee as: an individual who has fled their country “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.” But, as their website admits, in the 63 years since the convention, the dynamics of displacement have radically changed. This definition of a refugee does not account for the millions of people currently displaced by natural disasters, droughts, desertification, sea level rise, population growth, or resource scarcity. Of course such ecological crises are also intricately enmeshed in sociopolitical conflicts, complicating attempts to redefine the refugee or to classify a new category of “climate refugees” or “environmental migrants.”

Currently, there are more refugees in the world than there has been since World War II (assumedly not including climate refugees). More than half of them are children, often traveling alone or in groups of other children. The situation is becoming more and more critical, as humanitarian groups and host nations struggle to accommodate peoples who often have no possibility of returning to their home country. The two refugee crises that seem most visible at the moment are in the United States and in Lebanon — both of which exemplify the complex mesh of nationalist, religious, and economic forces that preclude any ready or repeatable solution to the critically expanding global refugee crisis. Perhaps the most prominent researcher on the issue, the British environmentalist Norman Myers, estimated that the global climate refugee population in the mid-1990s was around 25 million, and predicted that the number could double by 2010 and that the number would max out at 200 or 250 million by 2050. In 2009, the Environmental Justice Foundation claimed that nearly 10% of the global population were at risk of displacement. However, these numbers have been criticized for lacking significant empirical evidence, a persistent problem because of the difficulty of defining an “environmental migrant”. Other reasons such data are difficult to determine is that often, such migration occurs internally and across relatively short distances. Moreover, there are many different, fundamentally unpredictable potential causes and factors, such as natural disasters like earthquakes and hurricanes, as well as the wealth and preparedness of particular regions. And as populations continue to increase and global warming accelerates beyond expectations, the future seems more and more unknowable.While many of the issues of a refugee camp are socioeconomic, they are rooted in architecture, around basic needs for shelter and infrastructure.

Regardless, the situation is – and will be – devastating to both affected communities and larger global systems. While it is the wealthy industrialized countries that take the lion’s share of the blame for global warming, it will be the poorer countries that will suffer the most. And, in a circular consequence, areas that are already plagued by conflict will have more climate-generated conflicts. Neil Adger, a professor of geography at Exeter University, explains, “The impact of conflict in destabilising regions, wiping out infrastructure, not allowing the state to fulfill its social contract to protect its own people… conflict itself is making people more vulnerable to climate change."

Under the weight of this pressing urgency, the actual mechanics of refugee camps must be reexamined. By nature of their emergence under the weight of disaster, camps tend to desperately lack basic resources, such as water, food, and power. This scarcity leads to a greater dependence of the surrounding environment, which Julie Cook of the Global Post articulates as a circular problem, as the camps tend to cause significant environmental degradation such as deforestation. In addition, refugee camps, such as Zaatari in Jordan, are often hotbeds for disease due to unsanitary conditions and lack of medicine. Populated by desperate and shell-shocked peoples, camps can easily descend into violence, particularly against women. Simon Tisdall of the Guardian described how in 2012-2013, “UN and NGO workers were ‘shit-scared’ to enter parts of the camp, due to frequent riots, stonings, and gang attacks.” But while many of the issues of a refugee camp are socioeconomic, they are rooted in architecture, around basic needs for shelter and infrastructure.

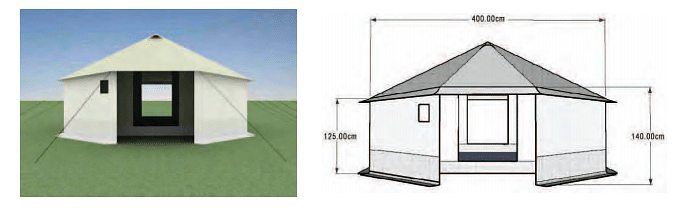

By far the most prevalent structures in many refugee camps – besides, perhaps, ad-hoc or informal design, for which it is difficult to find documentation or statistics – are those provided by the UNHCR. There are different typologies, but one of the most prevalent is the “Family Tent.” A small vestibule opens to a 16 square-meter base area without any partitions that is intended to house a family of five. The entire structure is packaged together, along with instructions and a repair kit, for less than $200 per unit. The casing is a polyester-cotton blend and has an intended lifespan of one year.

Problematically, many refugee camps are not populated by five-person families (a notion of the family unit based heavily on a US-American and Western European model). War and disasters destroy families, but rarely wholly. Children are often left parentless and forced to form their own groups. Refugee tents need to be more flexible and adaptable to accommodate diverse groupings without potentially exposing individuals to vulnerability in their sleeping places. Additionally, the unfortunate reality of refugee crises is that they are rarely short-lived. This puts significant strain on both the resources of the host country and on the physical architecture of the shelters. As Cook argues, sustainable agricultural practices and resource management are important tools that could help assuage the former problem. The latter one requires design solutions.

After the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan, Yasutaka Yoshimura Architects developed “Ex-Container”, to “achieve lower cost[s] with higher quality than normal temporary housing.” Utilizing shipping containers, which have standardized dimensions and have been readily adapted to architecture in many other projects, the Ex-Containers can be stacked vertically with a crane. The buildings are good-looking and could be lived in for quite a long time, although they are presumably too expensive for mass application in refugee camps. There have been other similar designs that make use of the ubiquity of shipping containers. However, such solutions are really only adaptable for countries with ports. Moreover, while shipping containers can be turned into shelters without glass or other design details, they still cost between $2500 to $4000 just to purchase. Still, for countries with coastal access, an advantage of shipping containers is that they can also transport food, water, and other supplies.

Designer Felix Stark of Formstark won the Red Dot Design Award, a prestigious competition sponsored by AT&T that tends to privilege socially-conscious designs, for his refugee shelter. Unique in attempting to include psychosocial considerations in the design, the shelter consists of 19 three-person rooms that are arranged around a central courtyard. The designers state, “The concept behind ‘sphere’ not only considers taking shelter from extreme weather conditions but also reestablishes the feeling of security and companionship without losing privacy.” Functionally similar to a Roman courtyard house, the outside layer is waterproof and thicker than the inside layer, which is permeable to allow air circulation*. Such a design could, theoretically, be manufactured for around the same price as the current UNHCR tents. While more adaptable to different family (or other) units, the large size could potentially pose the obverse problem of forcing vulnerable individuals or small families into living with dangerous persons.

Designed, in part, to address this problem of varying group sizes, Zip-Shelter is a “rapidly deployable shelter for cold or hot climate conditions, for use by refugees, migrants and for expeditions.” Easily transportable even on foot, this structure is made out of a material that provides insulation for even sub-zero temperatures. They can sleep two to ten people and are intended to be adaptable rather than uniform. Eventually, the material can be re-used to build more permanent structures. However, the Zip-Shelter does not seem to have been realized yet, nor its costs estimated.

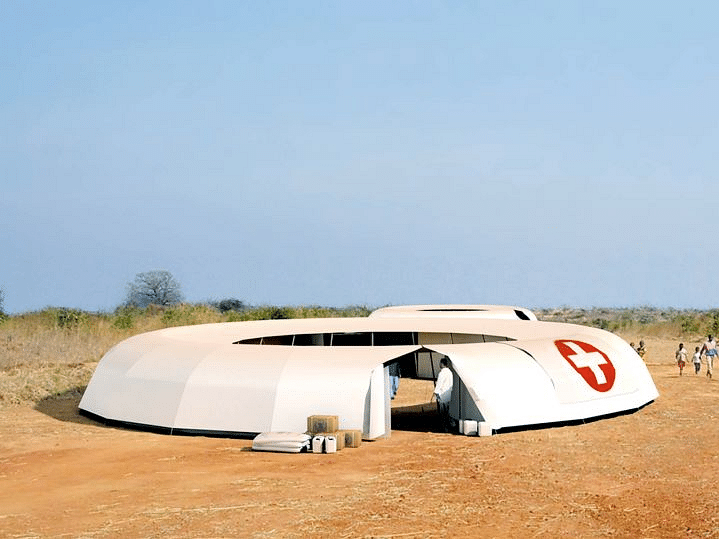

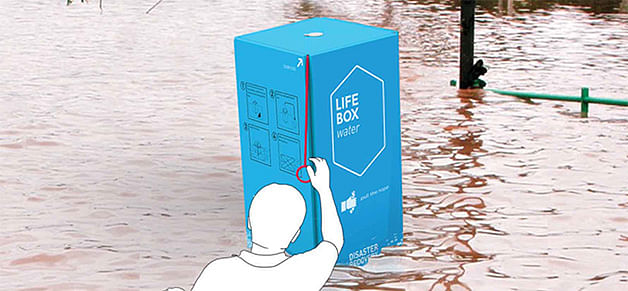

Life Box, another recipient of the red dot design award, is the work of designer Adem Onalan and is oriented around the problem of getting resources to places immediately after a disaster. The project consists of boxes that can be inflated to become shelters and include emergency supplies. There are three types: air, water, and land. The “air” type is for areas that can only be reached by plane and the shelter serves as a parachute, allowing air-drops. Water is for flooded areas, and the shelter can be inflated to serve as a flotation device and a temporary home. Land is for areas accessible by land. The project is exciting in its adaptability and usefulness, although it is not oriented towards long-term use so does not address many of the issues already articulated.

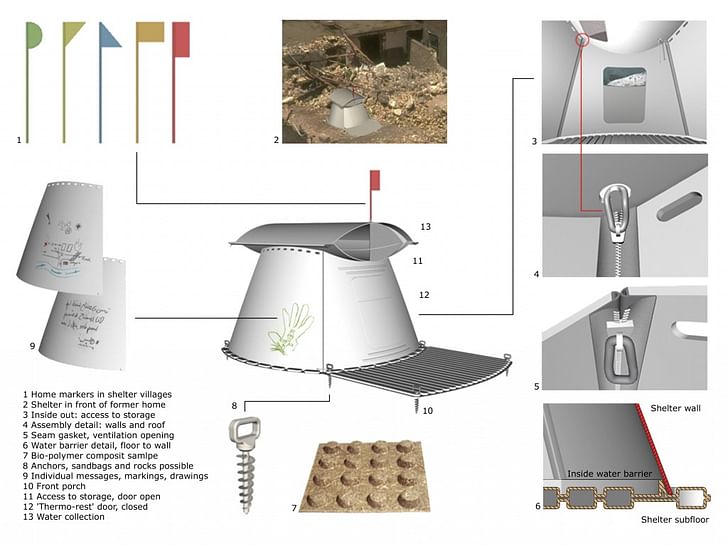

Abeer Seikaly won the Lexus Design Award for her “Weaving a home” designs. The project “reexamines the traditional architectural concept of tent shelters by creating a technical, structural fabric that expands to enclose and contracts for mobility while providing the comforts of contemporary life (heat, running water, electricity, storage, etc.).” This innovative shelter utilizes piping to naturally heat and cool the interior as water, collected in a rain catch, circulates. The structural fabric also helps with ventilation. Moreover, the whole dwelling can be collapsed to a very compact size.

The refugee appears as an extremity of the total social fact, rather than an integral component of it.

But a more pressing fact must be addressed: only one third of the global refugee population lives in camps, the vast majority live in urban areas. While providing more economic opportunities, such urban enclaves also present unique problems, as the UNHCR states: “refugees may not have legal documents that are respected, they may be vulnerable to exploitation, arrest and detention, and they can be in competition with the poorest local workers for the worst jobs.“ While the aforementioned designs are innovative and important, they do not entirely or adequately address the situation at hand. It is true that the architectural field has greatly expanded in the last few decades, taking into account greater urban, social, and ecological contexts, but there is still a dominant tendency to consider architecture as the design of a singular building. Therefore, architecture for disaster situations tends be oriented around an individual dwelling: the white tent. But the contemporary moment demands an architecture not simply for disasters but of disasters, and perhaps the greatest hindrance to this is the prevalence of the white tent as the dominant image of refugee crises. As such, the refugee remains a figure on the fringe, literally inhabiting the most basic unit of shelter, whose situation merits the bare minimum corresponding to the bareness of her life. The refugee appears as an extremity of the total social fact, rather than an integral component of it.

In a 1943 essay “We Refugees”, the political philosopher Hannah Arendt contends, “Refugees driven from country to country represent the vanguard of their peoples.” The ability for one population to be displaced opens up the future displacement of the whole population, as well as conjuring the political and juridical conditions through which every body becomes vulnerable to the loss of citizenhood and its concordant rights. This is a uniquely modern paradigm, one that could only occur with the formalization of citizenship that accompanied the emergence of the nation-state. While people have been expelled from their homes throughout history, it was only with the first World War that refugees occurred as a mass phenomenon – and it must be noted that there has still never been a “return to normalcy.”

In Precarious Life: the Powers of Mourning and Violence, philosopher Judith Butler articulates the fundamental interdependence of humans as social agents, that if another’s body can be injured, then mine is vulnerable as well. She writes, “When we lose certain people, or when we are dispossessed from a place, or a community, we may simply feel that we are undergoing something temporary, that mourning will be over and some restoration of prior order will be achieved. But maybe when we undergo what we do, something about who we are is revealed, something that delineates the ties we have to others, that shows us that these ties constitute what we are, ties or bonds that compose us” (22). Extrapolating from her thinking, I would like to contend that the home of the refugee must be thought of as my home. That as long as an other is a refugee, I am a refugee-to-be. The brutal facts of climate change transforms this projection from solely philosophical thinking to realist speculation. No amount of greenwashing will remove the blood from our hands.

What does this do to architecture? The maintenance of buildings accounts for nearly 50% of energy usage and construction is one of the most wasteful human practices, particularly as it tends to follow demolition. Architecture is complicit in climate change so long as it is maintained chiefly as the construction of new buildings. This is the bare fact: the architecture of today is creating the refugees of the future. No amount of greenwashing will remove the blood from our hands. While designing new temporary or semi-permanent housing for refugee camps is certainly a vital practice, I believe that a more profound shift in architectural thinking is necessary, towards an architecture that comes out of disasters, that first comprehends itself as a disaster. Rather than thinking of Gaza or Nairobi or Zaatari as the extremes, they should be considered laboratories for the cities of our future.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.