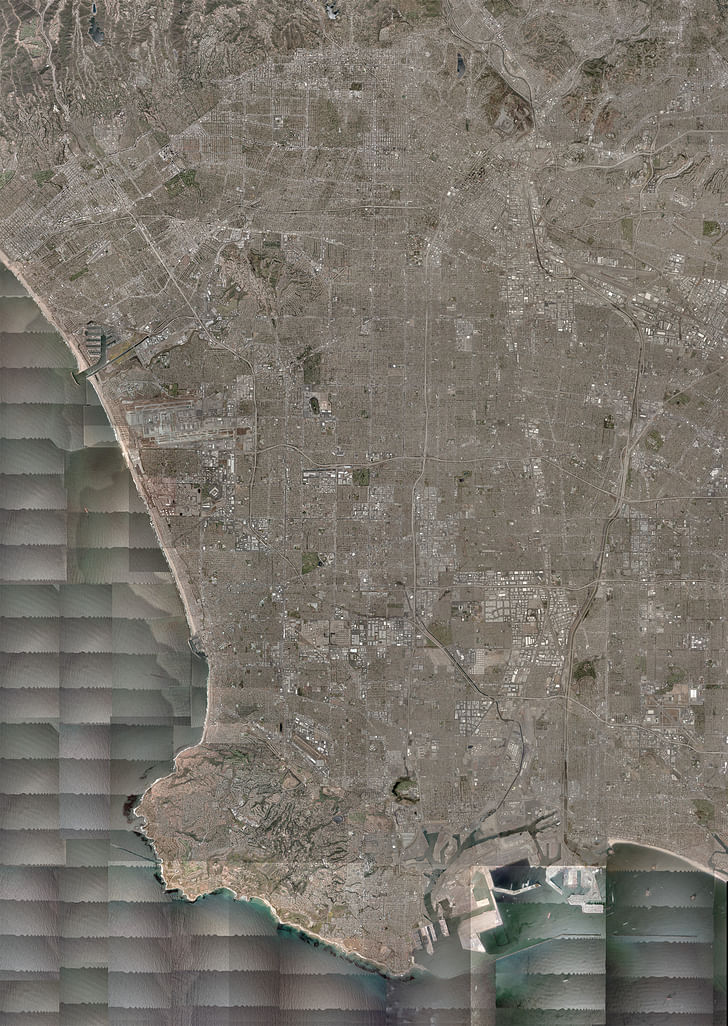

No single image can contain a city, particularly one as large as Los Angeles. But through the accumulation of many, it may be possible that the irreducible complexity of a city can become slightly more legible. Pairing aerial photographs by Los Angeles-based Lane Barden with a geo-mapping project by the German-American duo Benedikt Groß and Joseph K. Lee, the summer exhibition of the Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Design presents two distinct perspectives with which to view the city.

Barden’s Linear City project traces immense infrastructural elements of Los Angeles as they cut through the city, highlighting these often-overlooked but vital components of urban ecologies. Groß and Lee’s Big Atlas of LA Pools is a multifaceted project documenting the private pools of the city through publicly accessible data and imagery, drawing attention to the unsustainable practices of Angelenos. With new reports that 33% of the state is currently in “exceptional drought” conditions, the exhibit feels particularly timely.

Barden documented three significant infrastructural conduits: the L.A. River, the Alameda Corridor railroad trench, and Wilshire Boulevard. His photographs are laid out in three rows – one for each conduit – and printed on a large canvas that stretches along the entirety of the gallery space’s eastern wall. At work here is a subtle but effective play of linear elements that bring out the architecture of the space itself, which is long and narrow. In another gallery, the photographs could have felt cramped and busy because, fundamentally, there are too many of them. While many of the individual shots are quite beautiful, together they drown each other out. That being said, the photographs are presented together as a single Wilshire is not just a street or series of buildings, but also the cars and the people that pass through it; the L.A. River is not just its banks but also the water coursing (or not) through it; the Alameda Corridor is not just its tracks but the cargo – and economy – carried along them.work. They seem much more affective if viewed as a stand-in for what is being depicted, as fragments that can only begin to represent the whole collectively. In this sense, the superabundance of images is successful. The project’s overwhelming scale parallels the uncontainable massiveness of the subject matter.

Some of the photographs are quite familiar views for a Los Angeles native. But when they are coupled with more unusual and rarely-seen locations, they begin to stop making sense as they are revealed to be just a single part of an otherwise unwieldy mass. It is in this juxtaposition of the recognizable and the unrecognizable fragments that something like the “whole thing” begins to emerge. Barden’s piece works best in these uncanny moments. Wilshire Boulevard becomes more than just a series of intersections but an object in its own right, one that defines and determines a significant portion of an intricate urban system. This is even more striking with Barden’s images of the L.A. River that capture the shifts from bucolic verdancy to concrete-lined urbanity. The Alameda Corridor, the least publicly visible of the three, is more surprising than the other two, its relative unfamiliarity from the outset intensifying the difficulty of recognizing something so huge as a whole.

Haunting Barden’s images is the understanding that Wilshire is not just a street or series of buildings, but also the cars and the people that pass through it; the L.A. River is not just its banks but also the water coursing (or not) through it; the Alameda Corridor is not just its tracks but the cargo – and economy – carried along them. In choosing to document infrastructure, Barden presumably wants to point it out as an often unnoticed, but fundamentally vital, aspect of urban life. Scale, however, is not the only reason infrastructure seems to withdraw from intelligibility. Barden seems uncertain of whether to try to make sense of things or to revel in their lack of sense, and in the process the images become rather formulaic and don’t accomplish much of either.

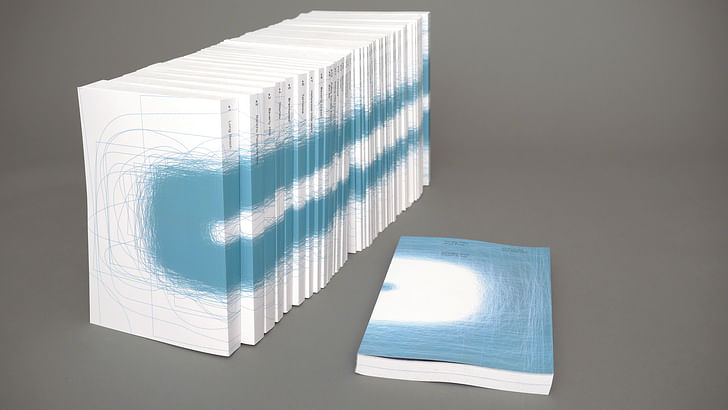

On the opposite wall, the linearity of Barden’s images is complemented by Groß and Lee’s study of Los Angeles pools, materialized in a series of books displayed on a long shelf. Organized by neighborhood, the books altogether contain aerial images of every pool in Los Angeles. That some of the volumes are so much thicker than others creates a neat visual condensation of the city’s geo-economic segregation. While there is obviously too much information to digest in a single visit, the books lend themselves well to the casual perusing facilitated by a gallery context.

Along the floor are low boxes, printed with data visualizations drawn from Groß and Lee’s research into the pools. The images themselves are aesthetically remarkable; in particular, one consists of every pool size in the city overlaid on top of one another, creating a seductively abstract image. However, they do not add much new information to the exhibition, serving more of a visual than a conceptual purpose.

That being said, the data-driven works of Groß and Lee actually seem to speak more in their silences than anything else — as in, the conceptual vitality of the project is structured into One cannot keep ecology at arm’s length. The clinical standpoint of the datatician or the aerial photographer is like that of the sociologist studying a society and forgetting that she herself is part of it.the research, and therefore does not need to be stated. By utilizing public mapping databases to document private pools, the duo are already troubling the tidy distinctions between public and private spheres. There is no need to invoke socioeconomics directly when the books themselves are a visual representation of them. Likewise, conversations about drought and resource management and excess and luxury don’t require vocalization. After all, today it is impossible to turn on sprinklers in this city without these rehearsed discourses playing out in one’s head. The operability of the project despite their silence is a measure of success.

However, in the exhibition’s supplementary text, the Big Atlas of LA Pools is described as displaying “Angelino’s perverse resistance to native ecologies.” This momentary incursion of the polemical into their project reveals a crack in their attempt to assume an objective, aloof position. Not only does this framing reveal a particular orientation to their research, it also puts the very possibility of an outside position into question. After all, the datatician also has “a perverse resistance to native ecologies.” Data centers, presumably including the ones containing the material that Groß and Lee appropriated in their work, are among California’s biggest consumers of energy.

The most visible common denominator of the show is that the artists involved have distanced themselves from their subjects of inquiry. It is precisely this cool clinacility that enables the works in the first place; only through the literally elevated position of the helicopter or the satellite is it possible to consider conceptual objects of such a large scale as infrastructure. Seen just in its parts, infrastructure goes unnoticed. But from above the parts begin to compose a whole, which is, fundamentally, ecological. It is therefore no coincidence that the various subjects of inquiry in the exhibit all live in the uneasy division of the natural and the man-made. For Barden, Groß and Lee, the position and involvement of humans in a greater ecology is only clear from high above.

However, presenting ecological conditions at this scale also renders them abstract and often unintelligible. One cannot keep ecology at arm’s length. The clinical standpoint of the datatician or the aerial photographer is like that of the sociologist studying a society and forgetting that she herself is part of it. Fundamentally, the ecological reality that is the most interesting aspect of both of the projects becomes neutralized as it is aesthetized. Beautiful, interesting images may provoke thought, but they do not produce fear, anxiety, depression or any of the other myriad emotions that they probably should.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

3 Comments

This is the architect's dilemma: to simultaneously understand the god's-eye view and the close-enough-to-touch view. We have to be smart enough to operate at both these levels and every infinite level in between.

This reminds me of that story of the 1933 CIAM meeting. Participants compared scale plan/maps of major cities around the world. Neutra's graphic of LA covered a wall and then some.

"Mon Dieu!" cried Corbu, wiping his circular spectacles to make sure he was seeing correctly. (Okay, I made up the last part.)

The trouble with a bird's eye view of Los Angeles is that you can get a bird's eye view from the ground – and it is this solely unique character of Los Angeles that has made me love this city.

The cover photo of this article is a perfect example of the multiple layers of elevational fabric that one experiences in Los Angeles in a matter of minutes. That is a photo of Elysian Park and Elysian Valley / Frogtown. And within 5 minutes, you can be face to face with the LA River, where the viewer is weighed down with such a horizontal mode of vision, or you can be on top of Elysian Park (Dodgers Stadium) with an almost 360 degree view of Los Aneles and beyond. And you have these moments everywhere in Los Angeles, wether it be the transition between Vermont Ave (low) and Griffith Park (High), or Hollywood Blvd (low) and Barnsdall Park (High), or the weaving of views and the sense of floating on the 105, 110, 10, Angeles Crest, and the Gold Line to Pasadena.

The urban fabric of LA fluctuates not only in demographic and building aesthetic / typologies, but also in visual connection. What is beautiful about this is that anyone can experience this sense of height or depth irrespective of demographic placement. Some working class neighborhoods in East and Central LA have some of the best views in the city, while some of the most affluent neighborhoods are barred away in gates.

What these views of Los Angeles convey are a lot of important elements that urban designers / architects / and thinkers must take into consideration:

A ) This environment of this city is in charge. Los Angeles' fabric is more environmental (natural) than urban (hard), and it will always be the case. If one looks at the sidewalks of Los Angeles, they are always uprooted due to the earthquake shifts and the relentless response that mother nature will not be restrained by concrete and steel.

B ) These views of Los Angeles also convey how young Los Angeles truly is as a city. It's history is more so rooted in Modernism than any other "typology." Los Angeles is still relatively flat, and I know many urban thinkers are drooling at the idea of a tall and dense Los Angeles, which is happening, but densification is natural. What is more important is Los Angeles' response to densification. There are many plans of densifying pockets of Los Angeles with tall buildings but that is no different than suburbs – just taller. It's disconnection, and disconnection is not the solution, especially for Los Angeles which is one of the most disconnected cities in the U.S. Los Angeles needs a holistic infrastructural plan that connects the city in a more efficient and fair manner. And these views of Los Angeles give you great ideas of how the city can be connected on multiple levels, literally. From as low as the Subway and the LA River, to as high as the Freeways and the Light Rails. This city has a lot of potential to be and do something we have never seen before.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.