by William Galloway

Sometimes it is possible to catch a group of people who are literally taking their first steps towards something interesting. If luck is on your side you can find out what they are thinking about - before hindsight settles in and the interesting things have become normal, and the answers to questions are all pre-digested. If the timing is right it is possible to learn a bit about what it is like to be an up-start.

Not so long ago I was able to sit down over skype and coffee and conduct an interview with just such a group. They call themselves 5468796 Architecture*. They are a group of architects who have settled in Winnipeg, a mid-sized city in the middle of the Canadian prairies. The office began when two of its principals built their own flats, and their work was noticed by a developer who offered them a chance to build something interesting. They took a leap of faith, quit their jobs, and three years later they have expanded to twelve, are working on more than a dozen projects, were awarded with a P/A award this year, will soon be anointed with a major international prize for the recently finished CUBE project, and are now seeing their work come to fruition as projects enter the construction stage.

Before getting too far, I should confess that I went to grad school with two of the principals, Sasa Radulovic and Johanna Hurme. As Up-starts they are interesting for the work they are doing, but also for the way they have chosen to run their office, which is a work in progress in itself. Their goal is to create a kind of informal collective. True to that ambition the interview was not with a single person, but with a group - members were dropping in and out fairly constantly, and quite often one person finished the thoughts of another. For the sake of convenience I have put a name before the comments, but the reality was something messier. I have tried to capture some of that roughness here without losing too much clarity.

* 5468796 Architecture = Sasa Radulovic, Johanna Hurme, Colin Neufeld, Ken Borton, Mandy Aldcorn, Sharon Ackerman, Aynslee Hurdal, Grant Labossiere, Cristina Ionescu, Shannon Wiebe, Maria Amagatsu, Michelle Heath

William Galloway (Bill) – I want to start with the basic and predictable. Questions like this are usually not so revealing, but I think in your case could be important. For example, tell me the origins of your office name.

Johanna - The source of our name is our incorporation number, a record in history of a particular time in the spring of 2007 that it came up in the queue of Manitoba corporation numbers. When walking back from the government office we simultaneously came up with the idea of generating a barcode from the number. In other words by scanning our business card at a Wal-Mart you could find out what architecture is worth today. More seriously, we wanted the name to be generic enough that anyone of our guys could take ownership of it.

↑ Click image to enlarge

5468796 office portrait

Bill – It’s ironic, because my first thought upon hearing your office name was Patrick McGoohan declaring “I am not a number!” but for you it means something liberating. The barcode as a symbol for a kind of friendly anarchy.

With that in mind, can you tell me what are you working on right now?

Johanna + Sasa - We have about 30 million dollars worth of construction going on right now, all in different phases. A university student center, several housing projects, a performance stage, hotels; there's an office building; two houses. The projects vary from rental to co-op, to shelter housing to condo development, to cottages. A lot of our projects have taken the whole 3 years of our existence to really get to the level where they are now actually getting built. The thing we are noticing is that there has been this sort of climb towards getting building permit documents out to the city, and now finally that is through and they are getting built. All approximately at the same time. We used to be in design mode all the time, and then we were in working drawing mode all the time. And now we are in the project management mode, a lot of the office is...it is sort of nerve wracking, the time it takes.

Bill – Are any of the works you are doing now the one that made it possible to start your own office? Sorry, let me be more blunt -how did you make the leap from working for someone else to opening up shop on your own?

Johanna – At our old office we had worked with a developer on a 40 cottage development in Ontario in the Lake Country there, and that was a project that we thought...well, the reason he had approached the office was that he had seen our condos, our personal homes. That was the reason he approached [the office we were working at] to do the project. So we did that project and it was finished to a point...and then he had an idea to do a different development. He found some new land...and we thought well if ever there would be an opportunity to do this for ourselves...

Sasa - It was basically that we felt we were able to get the work, right? So that's one of the things. The other thing was why not try, because then at least our families will at least get the financial benefit out of it.

Johanna - But it wasn't the financial side that pushed it. We felt the energy that we sometimes spent ended up being compromised or going in a different direction in the [old] office, and we thought we could spend that same energy pulling in a direction we whole-heartedly believed in, and we could maybe get better results that way.

Bill - And it all started because someone saw the condos you had built for yourselves.

Johanna - That's right. If you are looking back for a starting point, that was one thing that paid off.

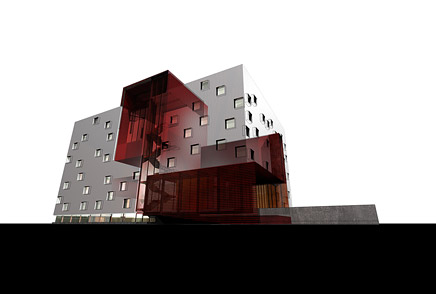

↑ Click image to enlarge

The First project – “Big Brother/Little Sister” condominium

[While we are chatting more staff pour into the conference room. I am speaking to the collective.]

Bill - Maybe you can all answer this. Years ago, Sasa and I talked about his belief that it should be possible to run an international office from Winnipeg, one that could compete not only for local work but for the large projects that are taking place all round the world. It was sort of just an idea then, and I wonder if you think it is possible now that you have taken steps in that direction?

All – Yes!

Sasa - What's the measurement of that? What is international? When we discussed this it was the idea of doing it out of here because good work can be done anywhere. So far we have done it for a radius of 2 kilometers. We are not really international yet.

Bill – The reason I ask is because when we were in grad school it felt like the internet and the power of personal computing was changing things, so that location wasn’t going to matter anymore. In hindsight, and with an office to run in Tokyo myself, it seems that what is most important is local access to people who want to build interesting things. How does that work for you in Winnipeg? That is, you are both from Europe, so when it comes right down to it, you don’t actually have to be in Winnipeg. Is there a reason you are there?

Sasa - Doing competitions was an escapism. We were under the impression that what we were doing here could not be as good as the work done elsewhere. It was an idea that we were trying to break out of this market. But we have realised since that this city is full of opportunity. We don't need to look for an escape.

So if we do competitions now it would be to try to compare quality maybe and try to experiment with typologies maybe that we don't touch here, for various reasons. It isn't that we can't do the projects here anymore. Do you guys agree with that?

Johanna - Yes. We have discovered that there are so many developers and so many people in Winnipeg who are hungry for good end products. I remember growing up, so to speak, with the thought instilled in my head that you can't talk to clients about concepts, which is completely different from reality.

Bill - You know, the people we are working with here (in Tokyo), most of our clients are in the financial industry, bankers, and so on and they have conservative sensibilities. We sometimes find ourselves trying to explain why something that isn't in a magazine yet is safe to try out. It’s ironic, it sounds like the people we are working with here are more conservative than the ones you are working with in Winnipeg.

Sasa - It is not to say that we don't challenge our clients. We seem to have, with every one of our clients, to have gone through an education process.

Johanna - We did have one client who came in and said, look guys I want an award winning project. And that was the greatest ever to get a brief on. And we were finally able to deliver, because it is the project that we won the PA award for.

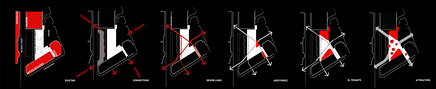

↑ Click image to enlarge

BGBX project – diagrams

↑ Click image to enlarge

BGBX project – Aerial

↑ Click image to enlarge

BGBX - street

Sharon - In Winnipeg, clients recognize quality but I think they associate quality with expense. So the thing this office has been really successful at doing is figuring out ways to have an amazing project that doesn't sacrifice quality, that actually gives an enhancement in quality, but is able to deliver by finding ways to maximise budget in other areas. Everyone is happy, and they get on board with the innovation because they see what is delivered.

Johanna - One of the things we tell our clients recently is that we want to look at the project. That means we maybe need to think harder, and therefore spend more time and money at our end and through that process actually find ways to save money, if you look at the bottom line, at the end. If you look at the project holistically it meets all the criteria we were given at the beginning.

Sasa - I think the thing is we don't take systems for granted. Architecture has very much become a specification profession. The systems are developed to a point where, if it is a curtain wall you have three suppliers and they have their systems and you pick one that you think you can afford. And you apply that over 70% percent of the building. Of course you have to use some of those systems, but we don't take them for granted either. So it is always this issue of budget allocation that we are always trying to take advantage of. We don't work on projects where money can be spent everywhere. We aren't Herzog and DeMeuron who build for 5-6000 dollars /square foot. This latest project, the one that won an award, is being constructed for 145-150 dollars per ft2. Which is low. Well, that makes us think we can't do anything conventional anymore, because we can't afford anything conventional. That‘s important.

Johanna - One more thing We are trying to constantly find the right relationships between who is building the project, where the materials are coming from, what systems or props are they comfortable working with, and what crew they can get on site. We are not perfect at it by any means but we are just on the verge of discovering the only way we can deliver something better is if we capitalise on the relationships.

↑ Click image to enlarge

youCUBE

Bill – If I can reminisce again, when we were younger we spoke about doing everything as a group, not with just one person in charge, a sort of ego-less approach to design. How do you do that now, whether it is sharing credit, running an office, setting up projects?

Sasa - I am not going to speak to that myself. I am not sure we are doing as good a job as we can.

Johanna - We are trying to figure it out. It’s not something that happens very easily. There is at least one project for every person in the office can take some claim on.

Well for example there is one project that Sasa and I have no claim on that is being built and it's great. It’s a great project.

Sharon - Absolutely. Maybe they are being a bit modest. The name of the firm is definitely representing this collective. There is an understanding that that is how we want to be working. We are all working around a single table in the office. There is not sense of hierarchy and everyone is welcome to participate as much as they can and as much time they have. Also, when projects are being recognised they are recognised as the team, and so I know for myself that I am grateful for that sense of inclusion.

In some practical ways it is not always as easy for everyone to be inputting in an equal way to the projects. But that is partly because of the amount of energy that Sasa and Johanna are putting into every piece of work.

Sharon - I had worked with Sasa and Johanna on many competitions before coming to this office. When we did that it was more successful, but it is maybe not as practical in a certain sense. Having said that I have been working here for a few months and have already been given more responsibility and more autonomy in those few months than any place I have worked.

Ken - Well, you definitely get the opportunity to sink or swim, and because of the work load and the amount of work coming into the office we sort of jump into running 4 million dollar projects within a year of coming out of school. It is probably a good way to learn quickly, because we make a lot of early mistakes and get them out of the way.

It’s stressful at times, and new all the time. We are doing something every day that is new, so it is a great learning process. But it's stressful too; we have to make use of the entire office to gather enough energy and thoughts on things to know we are working in the right direction. It takes the entire team to make it work. When the team is all working together we get pretty far with things.

Sasa - The fact is that everyone is capable.

Johanna - We recently did a project where, for some reason we were able to swing the time so that we basically spent a week, the entire office, to work through design concepts. If we were only able to do that for every design project it would be amazing. BUT it is sort of hard to put everything on hold for a week though I find that the project comes out better.

Bill - Do you use the entire office in every project?

Sasa - In early days we tried to, but recently there are no large projects coming in, and partially it is time pressure.

Bill - So is it safe to say the idea of a collective is kind of working?

Sasa - It is a work in progress.

You know, one thing that is becoming obvious, is the fact that as we are getting more experienced all of us, at things. Two years ago Johanna and I were at a level where people in the office are now. There is a big learning curve for us and a steep learning curve for everyone else. But BOTH learning curves are advancing - which enables us all to be much more productive collectively, once we all have the knowledge and experience because we can interchange much more easily.

Johanna - It is not just that we can be much more productive, it is that ideas can be questioned at every level when we can all talk at the same level of detail, at the same level of knowledge.

Sasa - We designed this project two years ago that won an award. There were five of us working, and only two were out of school already, so we were discussing cladding of the building and we asked Ken what he thought of it, and his answer was that he didn't know what else was out there.

Ken - It seemed cool enough, right. But I couldn’t contribute to that discussion at the same level, because I didn't have the context of all the stuff that is available and needed time to learn. Which is a perfect example. We all need time to grow before we can be...even better.

↑ Click image to enlarge

OMS Stage from park

↑ Click image to enlarge

OMS Stage interior

↑ Click image to enlarge

OMS stage jazz festival

Bill - As you get larger projects and have more people working with you, do you think you can continue to be collaborative, or have you peaked at the number you are at already?

Johanna - No but there is a question about how much you can grow and still maintain that affinity of sorts. I think we decided fairly early on we don't want to grow much more than where we are right now. If it means a few more people is ok, but no more than 20 or so.

Sasa - Manager meeting!

Johanna - Shush.

Bill - Steven Holl used to say that 11 was perfect. I am guessing that he is bigger now, but do you think his size makes his work worse? It certainly seems to be ok, even better.

Sasa - Well, I think there is a fundamental difference. One thing that disturbs us is that every project is designed by Steven Holl, period. Then there is the project architect and so on, and we think that those are the grounds on which you cannot grow. Because you can only be as good as Steven Holl is, and no better. That is one of the things I would like to get away from.

Johanna - Being only as good as Steven Holl is. Sure [smiling].

Sasa - If you get bigger and better projects then we are trying to learn to manage them all together. In a utopian project we would like to have 10 people who are all able to manage at the same level, so that on one project someone can act as a project manager and on another act as a draftsperson. Wouldn't that make for a marvelous working relationship?

Ken - if everyone is an architect in the office. We have talked about that, can that work? Where everyone is at an equal level, where everyone does all the groundwork and everyone does the design work, and everyone does all of that stuff...it is tricky to do, and it's kind of redundant maybe, and has its shortcomings for sure, but...

Bill - This is kind of related. At my former office in Japan that was how it was. Everyone was an architect. There was no such thing as a technician. You were either an architect or not, and that was it. Either you are just learning, starting, getting your license, or have 10 years of experience, or 20 years of experience, but everyone was an architect. That is the standard for me.

Johanna - How did that work?

Bill - It worked fine. A lot of what you are describing is actually how I always worked. There are no office partitions; everyone works at one big table. That is totally normal. If you have a boss off in the corner somewhere that would be strange I would say in the Japanese system. And how it worked, well, it was usually the boss would say you, you, and you, you three are working on this project, show me what you've got, and he would oversee us, but 2 or 3 of us would work on a project together and we would figure it out ourselves. How it worked was always changing. The mix of people was always different but usually there was a senior guy mixed with a junior. That was why I was able, much like Ken was saying, to sit down on the first day of the job and be handed a project to design a church on my own. And later I was running 15 million dollar projects while the architect beside me, who was technically my senior, was working as my draftsman. The point was not hierarchy but to make good architecture and who was in control of any project was always kind of fuzzy. It could be frustrating at times but I think was a fantastic way to learn fast and to learn to work in teams. Maybe it is only really possible in Japan I don't know, but it seems to be how OMA and Toyo Ito and other large firms are able to use the talent of everyone to keep things fresh. Or maybe that is just my fantasy.

Johanna - That was not where we came from. It was different.

Ken - I think offices in North America are very different. Here there is a management team, usually sitting in a glass cubicle.

Bill - So you are actually all Japanese. You just didn’t know it!

OK, changing subject a bit, how do you start a new project then, if that is the approach to working?

Sasa - We start with a conversation. We don't start with Johanna going home and coming back the next day with a concept. We don't do it that way. We don't make a water color theme of it either.

Johanna - The common theme is how to forget everything we know about a cottage or a housing project. How can we think about it from the perspective of what we would do if we didn't know anything about it to start with? I find that often we were able to get to much better questions about it if we don't make those assumptions and don't rely on knowledge of typologies that already exist. That may come in later, but that sort of seems to be a common theme in our work.

Ken - There is almost always this sort of immediate thing that shapes the projects right away is site constraints because the program is usually three times what the site can handle and we have to find a way to squeeze it into the site, and sometimes it flows over the property lines and sometimes it is just creatively crammed in there... but that is what sort of starts things.

↑ Click image to enlarge

5468796-e_regulr house

Bill - Is most of the work developer driven?

Ken - It's a mix. Right now about 1/3rd developer, 1/3rd private owner, and 1/3rd public work.

Johanna - We don't have any self-inflicted work.

Bill – But it does seem you have a large input in the direction things go in terms of the themes you explore. Do you have any social ambitions with your work?

Sasa - That is an interesting question because all of the work we have done are at some level social, and communal. Much more so than any other project we might see from a big developer. By saying that, I am not quite answering your question directly, but they do incorporate...they are all designed with some kind of social responsibility in mind. Not only for the tenants, but for the city they are in. Successful or not that is what we are going after.

Johanna - There are two threads to that. One is to try and figure out what the public realm is among the units, and to kind of squeeze the private space so it invites people to participate in the communal. Then how do we make that communal space and invest resources and perhaps money in the communal space instead of the units themselves.

Ken - And that is the hardest part to convince developers of.

Johanna - It’s not sellable.

Bill -That was what I was getting at before. How do you convince the people who are funding a project to go against the over-riding instinct to earn as much money as possible per square foot (or meter).

Ken - Well, fortunately we have developers who are open to that. They come to us with a goal in mind, and if we can meet that and do other stuff too that maybe helps sales and maybe doesn't, that they don't care about but we do. When we put all that together there seems to be ears for that.

Johanna - One of the interesting things is that for one of our projects, the developer is not selling it per square foot. Instead he is selling it per unit, because if he simply extrapolated the numbers he would never get to where he wants it to be. But when buyers see the space and the kind of quality they can have they can see themselves investing. THEY don't think about it per square foot. The other thing we have been working at a lot is trying to convince people, like developers in general, that we can live in smaller spaces than we are used to now in North America. It's blatantly obvious where we come from – that is, from Europan standards. So we are working on finding out how to make smaller spaces feel larger than they actually are.

Johanna - I recently had a very candid conversation with an engineer. He was selling photovoltaic systems and was very proud of his own home, which he was showing to us. He had put every gadget and every possible mechanical component on the house to make it more sustainable. But when we looked at pictures of it, it was 4000 square feet, a 4 story big honker of a building. It begs the question, what is the point of building this sort of things when it could be possible to just reduce the footprint of the house by what 50%. You would still be able to live there, have plenty of room (it was 2 people in the house) and never have to invest in the capital attached to the gadgets.

That seems to be the prevailing process here. Everyone wants to be sustainable but the way to get there is through mechanical components instead of looking at yourself in the mirror and seeing how much you really need.

Bill - It’s the engineer’s disease. Solve the problems caused by technology with MORE technology.

Bill - What is your view of the city? Today everyone is talking about the city. It is the main theme of Biennales and Triennales, in Rotterdam, Hong Kong, wherever. I don't know if Winnipeg would ever host a Biennale but if they did it would probably be about the city. Do you try to deal with the city in your work? Or do you try instead to make buildings that are more self-contained things by themselves? I don't want to prejudice your answer but the reason I ask is because the work you do does seem to be less about making objects and more about making places in the center. Is that correct to say?

Sasa - I don't think any of our buildings are self-contained. Half of our projects that are begun from a clean slate, not additions or similar, are "city" projects. Now, a lot of our projects are downtown, which helps, but they are urban by nature and one way or another are urban. This is not really answering the question you are asking I think. To us it is very important to address the city...

Johanna - but whether we have some sort of scheme to address the city...I don't think we are that involved in the city anymore. For us, I guess each project we do is a prod, to the profession, and maybe for the city.

Ken - It is on a much smaller block scale. I don't know if that is just because we don't have the work that allows us to address the issues yet, or if it’s just that we haven't had time to examine the ideas to the full extent. But when we do proposals, it is part of our talk, our work at the early stages of a project. Like the University of Winnipeg project it is about using the downtown. But for most of our work they don't really have a life beyond the block edge.

Johanna – In Winnipeg there is a lot of open space in the form of parking lots in the center, and the edges are entirely open so it is possible to grow continuously. What is mind-boggling is that in the city planning office everyone is scared of density. We feel that if there is anything Winnipeg could use it is density, tighter knit communities, tighter urban fabric everywhere. We found even in one of the denser walkable parts of the city that the limitations and the zoning by-laws that are in place really limit the kind of density you can achieve. And we have gone through battles and battles trying to get projects that push the zoning boundaries. And it is there that we deal with those kinds of things. But the streetscape is really empty here most of the time.

Bill - Do you want to deal with that?

Sasa - there is a broader role, which is one of sort of prodding the other architects of the city. One of the things that we said to ourselves when we started was that we could do better. Not better than other architects but better than the profession collectively. And the only way for us to prove our value, to the broader community, is by doing better work.

Bill – Which seems a good cue to speak more directly about some of your buildings.

Johanna - So here is a place where Sasa arrived at when he came to Canada as a refugee, and here he is, what 15 years later. It’s called Welcome Place.

↑ Click image to enlarge

Welcome Place diagram

↑ Click image to enlarge

Welcome Place rendering

Sasa - This is a building that is bursting in terms of program it is just bursting.

Ken - To have that much public space in that kind of building is impressive really. There is no room for anything in the building, it is maxed out as far as space, but we were able to work it out so that people would be able to exit their rooms and meet together and mix around. Without that it would have been just a dormitory. If we had taken that site and the program and put it together literally it would be nothing but a double loaded corridor. Row after row of apartment, row after row of offices, and nothing else, but we managed to find enough space to have a lounge on every floor, a roof top area, a courtyard, balconies.

Johanna - One project I am excited about is the Annex project. Just because of its urban context and the way it sort of puts thing in the program like a puzzle. It's a building that doesn't really have a facade at all.

Sasa - The University has taken over an old Greyhound terminal, and they have given us a program which is sort of the first stop for the new rapid bus transit for the city. It also includes the university bookstore, the student pub.

Johanna - There's also a clinic, and there will be retailers. It's sort of a mall space, but there is an interesting flux of university students and then the people coming on the bus and heading downtown.

Ken - It is a building that has no presence. The existing building is a space tucked under a 3 story parkade. So we wanted to break that space open.

Sasa - It is very curvilinear, which is something we haven't done so far.

↑ Click image to enlarge

University of Winnipeg Annex

↑ Click image to enlarge

University of Winnipeg Annex diagrams

↑ Click image to enlarge

University of Winnipeg Annex elevation

Johanna - We wanted to define the space even though it is this sort of left over landscape. It is supposed to be a place you travel through, but we wanted to make it interesting enough that it would have enough stickiness so that people will stay - so it becomes a vibrant arm, almost a new edge of the University of Winnipeg. Trying to figure out the movement and flow of the space so it could be taken advantage of and encouraged - opened up so that it becomes this playful landscape, a fertile ground for activity.

Ken - It becomes part of the everyday route. Instead of the building cutting off the university from the city, the addition opens it up.

Bill – And you say you don’t really deal with the city?

With that our time was up - as with all interesting conversations we stopped in the middle.

About the author/interviewer William Galloway :

Born on the Canadian Prairies.

Completed M.Arch at the University of Manitoba in 2001, and PhD in (sustainable) urban planning at the University of Tokyo in 2008.

In 2006, was co-founder of frontoffice , an architecture and planning office based in the middle of Tokyo.

Currently maintains his ties to academia as a lecturer at Waseda University.

He also keeps a pet blog .

Creative Commons License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License .

/Creative Commons License

I split my days between teaching at Toronto Metropolitan University and running my office frontoffice tokyo. frontoffice is a planning and architecture firm located in the heart of what is (for now) still the largest mega-city in the world, Tokyo. Taking advantage of our location we are ...

4 Comments

Welcome to UpStarts.

"Everyone wants to be sustainable but the way to get there is through mechanical components instead of looking at yourself in the mirror and seeing how much you really need."

Nice conversation Bill, thanks..

Nice interview. It makes you wonder about a lot of things, especially about the potential cure for engineer’s disease, poor souls.

Is obvious that as long as we stay blindly oriented to defining our needs through just a material explanation we will be never able to get a full HC (high comprehensive) picture of the whole or the solution, a way to sustainability.

Thank you 5468796 Architecture, and thank you Bill.

great interview. well written and both interesting office and interviewer.

Thank you, exciting interview, i finde some useful creative things for my progect and imagination

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.